Day of Disaster on Point Ellice Bridge

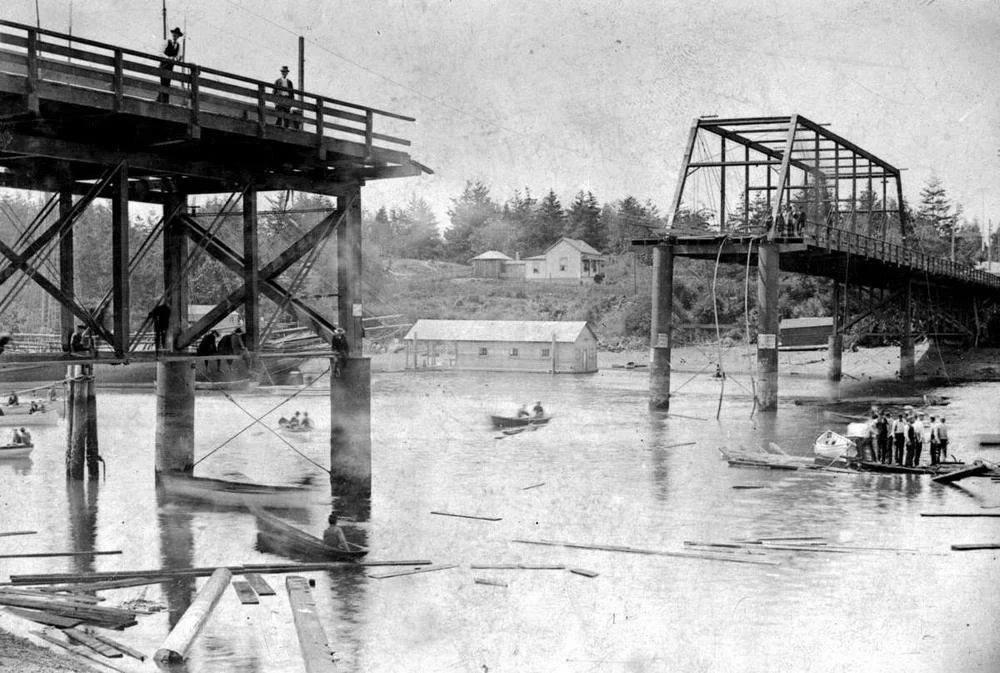

Last Sunday marked the 128th anniversary of the worst streetcar accident in North American history—the collapse of Victoria’s Point Ellice bridge from the weight of a trolley carrying more than twice its legal limit of holidayers. Within minutes, 55 people were dead, 27 injured.

Pulled from its watery grave, doomed streetcar No. 16. —BC Archives

Sadly, like so many disasters throughout history, it was the result of human error—not just so many people in the car, but a bridge that was well-known to be structurally challenged. The resulting court cases went on for years.

Today, this busy crossing is known as the Bay Street bridge.

* * * * *

In an eerie replay, in April 2011, the City of Victoria closed the historic Johnson Street railway bridge crossing to foot and bicycle traffic because engineers had found extensive corrosion in key structural supports. In some spots they could see daylight through the steel! Temporary repairs were deemed to be non viable for a bridge that was slated to be removed within a year.

So they chose to play it safe with total closure, the E&N Railway’s Dayliner having previously discontinued use because of the state of the bridge and ongoing track repairs.

According to Mayor Dean Fortin, the City’s last structural survey was in 2008 although engineering staff conducted weekly visual inspections and minor repairs as necessary. The Times Colonist, less than impressed, gave an editorial thumbs-down to the City for allowing what it referred to as the Blue Bridge (actually the adjacent bridge for road traffic), “to deteriorate so badly that rail traffic was ordered halted after an inspection.

“The bridge is to be removed next year, but the failure raises questions about what other infrastructure has been allowed to reach a dangerous failure point.”

Where’s the historical deja vu?

To answer this we have to go back to 1896 and to Victoria’s second most-used water crossing, the Point Ellice bridge as it was known before it became popularly if prosaically the Bay Street bridge. To this day, all of 128 years later, the disaster that occurred when the rickety span as it was then collapsed under the weight of a tramcar carrying 143 passengers, of whom 55 men, women and children subsequently drowned or were crushed—is Canada’s worst streetcar disaster ever.

It’s a classical case of human failure and oversight. The tramcar was overloaded by almost two and-half times its rated capacity of 60 passengers; it was Queen Victoria’s birthday, the sun was shining, and they were going to watch war games on Macaulay’s Plain, across the harbour in Esquimalt.

To get there they had to cross the Point Ellice bridge.

* * * * *

Built 1956-7, today’s Bay Street bridge that links Rock Bay and Victoria West is the sixth on this site, the third having failed disastrously with the loss of 55 lives. Point Ellice House, originally the Capt. Grant home whose lawn was used as a temporary morgue, is screened by the trees on the far shore.—Author’s Collection

Only 11 years old, and originally described as “elegant and substantial,” its four Pratt Truss spans consisted mostly of timbers with iron bracing supported on wood and iron piers. Its 34-foot width allowed for seven-foot-wide sidewalks on both sides. Six hundred and 40 feet long, including approaches, it had been built for horse-drawn and foot traffic at a cost of $10,000 ($373,271 today).

No thought was given to streetcars—they were yet five years in the city’s future.

In October 1890, the Colonist reported, “What was practically, though not formally, the inauguration of the Esquimalt extension of the street car line...when the first passenger car was run from the power house to Esquimalt town...”

What thought was given to running streetcars with their human cargoes over a bridge built for, at most, horse-drawn freight wagons? A bridge whose integrity for even that weight of traffic had already been publicly questioned? By the trolley company, by the City, apparently none—despite a warning by the San Francisco Bridge Co., designers and builders of the bridge, that streetcars were excessive. Apparently, news of the bridge being opened to trolley traffic had prompted a company representative to make a special trip to Victoria to advise against this usage.

During last Sunday’s commemorative tour of headstones linked to the Point Ellice bridge disaster, Old Cemeteries Society guide Yvonne Van Ruskenveld noted that his warning went unheeded.

No. 16, the trolley that crashed through the bridge was larger than this Victoria streetcar. It also was overloaded.—BC Archives

Three years later, while fully loaded with visitors from Washington State, streetcar No. 16—the very car that would carry its passengers to a watery grave—crossed the bridge immediately behind another trolley. A floor beam of the second span suddenly gave way and the tracks sagged three feet, but both trolleys made it safely across. Repairs were extensive enough that they took several weeks to complete.

As part of the subsequent inspection, “auger holes were bored in some of the bridge timbers” to determine their soundness. Incredibly, these holes were left uncaulked.

This was a perfect example of “misfeasance,” the legal term that’s sprinkled throughout subsequent legal proceedings that reached all the way to the highest court in the Empire, the Privy Council in London. There, Lord Haldane would scathingly comment, “The boring of the holes [in 1893] and leaving them so as to collect water, was calculated to rot this beam; that for four [sic] years it was left in that condition collecting water, and, if the evidence is to be believed, diffusing a state of rottenness all through the beam.”

The Right Honourable The Viscount Halden, KT, OM, PC, FRS, FSA, FBA scorned the state of the Point Ellice bridge prior to the catastrophe. —Wikipedia

His Lordship obviously believed that the test holes exposed the inner beam to moisture. As indeed they did. But the reality was much worse than that, the bore holes actually serving as perfect entry points for teredo worms, salt water’s rapacious version of termites!

The collapse of the bridge deck in 1893, determined to be the result of a broken ‘floor beam,’ even drew the attention of the provincial government’s Department of Lands and Works although nothing appears to have come of that.

The bridge was just eight years old.

* * * * *

Tuesday, May 26, 1896, dawned sunny and bright—a perfect day to celebrate Her Majesty’s birthday with all the pomp and ceremony of a patriotic British military outpost. Naval and army manoeuvres on Macaulay Plain on Victoria’s western shore were to be the highlight of the holiday, and 1000s of men, women and children eagerly headed there.

Every streetcar was worked to capacity, heading west from Campbell’s Corner in downtown Victoria in convoy-style, most of them carrying more than their rated capacity, with No. 16, a larger ‘theatre’ car, bringing up the rear. Its every seat was filled, children perched on parents’ laps or being held to the breast, aisles jammed with standing passengers and dozens more clinging to the roof and standing on the front and back platforms as the trolley—its own weight rated at 10 tons—approached the Point Ellice bridge from the east side.

A bridge that was already busy with pedestrians, a bicyclist and two carriages, with a pleasure boat passing below.

At precisely 1:50 p.m., as was later recalled, there was a loud cracking sound. The deck of the second span sagged then opened wide and the streetcar plunged downward to the water below. The faulty floor beam that precipitated the collapse would later be identified in various courtrooms as being perforated with holes—holes drilled but not caulked by City engineers.

Within seconds, No. 16 had settled on an angle on the bottom, 50 feet down, trapping and crushing those passengers on the right side amid a tangle of bridge debris. Many of those seated on the left of the car were able to escape through the windows as those riding on the roof and platforms, having been thrown free, swam for the nearby shore.

This photo shows that the entire second span had disappeared, —BC Archives

At first paralyzed with shock, witnesses on both shores quickly rushed to assist those in the water and to administer first aid. As word of the disaster flashed throughout the city, every available doctor joined in the rescue effort. Already, the grim task of gathering bodies was underway, the lawn of Capt. Grant’s nearby estate (today’s heritage Point Ellice House) being pressed into service as both an emergency ward and an open-air morgue.

Unable to assist, 1000s of spectators, many of them anxious for word of loved ones and friends, paced both shores.

Surrounded today by industrial development, Point Ellice House is an historic site and tourist attraction. A stroll of its landscaped grounds gives no sign of the horror that occurred there in May 1896. —Author’s Collection

By dusk, divers had recovered 46 bodies; how many remained missing was yet to be determined. Come dark, work had to be suspended because of the danger of bridge debris. Subsequent recovery efforts would confirm nine more dead. Those remains which had been recovered were removed from Capt. Grant’s lawn to the town market building next to City Hall.

A close-up view of the recovered No. 16. —BC Archives

The Victoria Daily Times font-page headline for may 27th said it all in just five words: DESOLATION REIGNS IN VICTORIA CITY.

Yesterday’s Calamity Apparent in All its Reality and Horror.

Families Decimated—Fathers, Mothers, Children and Friends are Lost.

The Latest Reports Give Between Forty-five and Fifty Bodies Recovered.

List of the Dead and Full Details of the Disaster—Inquest Proceedings.

(Already, an inquest, so unlike today’s tortuously slow legal system.)

Victoria went into stunned mourning. To put 55 victims in a community the size of Victoria in 1896 in context, Yvonne Van Ruskenveld calculated that would be the equivalent today of 1000 casualties in a single accident!

There followed, in the words of the Colonist, “a week of mourning”. Funeral processions filled the streets, some undertakers synchronizing the passage of their hearses so as to arrive at a cemetery together. Many merchants suspended business and the ongoing federal election campaign shut down for a week.

Already, however, the hard questions and the finger-pointing were underway. How could such a disaster happen? Who was to blame!

Obviously, there was need of an official inquiry, the coroner’s jury having been limited to dealing with identifying the dead and determining the obvious cause of death. The subsequent weeks-long inquiry brought out what many already knew or suspected: the Point Ellice bridge, even had it been in good condition, wasn’t up to the new loads imposed on it by streetcars and their passengers.

But the bridge wasn’t in good condition, thanks in great part to City engineers and their augers. A panicked administration ordered an immediate—and thorough—inspection of the Rock Bay and James Bay crossings.

Construction of a temporary pile bridge immediately south of the collapsed span was begun—under the eye of the City’s chief engineer—but work was delayed when the Dominion government insisted upon approving the site. In the meantime, most city pedestrians crossed to and from the west shore by way of the E&N Railway bridge.

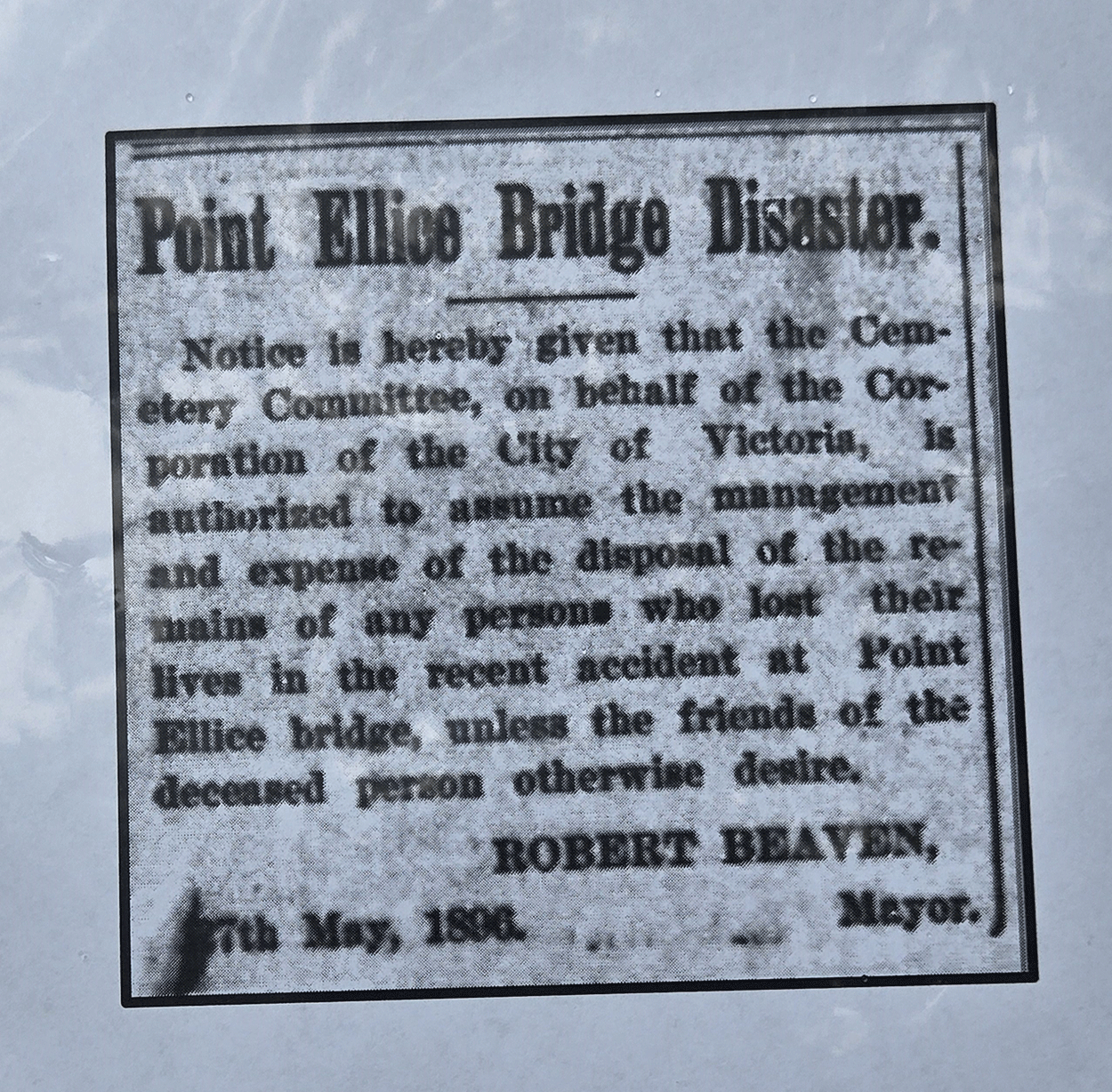

Besides fighting legal claims the City had to oversee the handling of some victims’ estates and seeing to their interment in Ross Bay Cemetery. —Courtesy Old Cemeteries Society

Four years passed before the damaged bridge was dynamited; the following year, a Washington State bridge and dredging company was awarded a contract to build a new crossing for $92,000—only to have it annulled by Mayor Beaven. He, Council and ratepayers were agreed that a new bridge should be built by a local firm. Not until April 1904 did the Victoria Machinery Depot’s ‘riveted bridge’ open to traffic.

It served until the present span was completed in 1957.

As we’ve seen, history almost repeated itself with the E&N bridge in 2011. Despite “weekly inspections” by City engineers, some structural supports had become so rusted through that they’d become almost transparent!

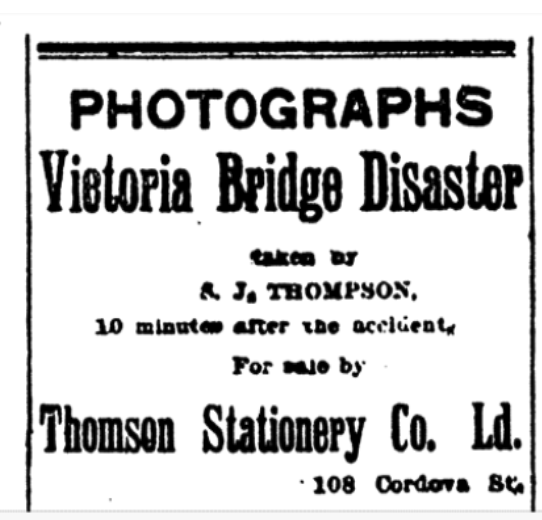

For some entrepreneurs tragedy is a business opportunity. That said, it’s because of private photographers that we have any photographic record of the Point Ellice Bridge disaster. —Courtesy Old Cemeteries Society

The ultimate result of the Point Ellice disaster was that the City of Victoria lost numerous lawsuits which had been filed against it. The legal wrangling went for years and all the way to the Privy Council in London, the highest court in the Empire, which ordered the City in June 1899 to pay $13,000 and $20,000 respectively to two women who’d lost their husbands in the collapse.

That left 49 more outstanding lawsuits! The City, persistent in denying any responsibility, fought and lost all but one of them—not against an aggrieved family member but against the Consolidated Railway Co., owners of the city’s street car system.

Astonishingly, that corporation was cleared of having any responsibility in the disaster despite having wittingly run overloaded cars on the Esquimalt run. But its suit charging the City of negligence was denied and it was financially ruined, leaving the City to fight its rearguard battles alone. When, finally, the legal wrangling ended, the City was out at least $150,000 ($5.6 million in today’s dollars).

As for public transit, within a year the British Columbia Electric Railway Co. was incorporated. Financed with British money and headquartered in London, this company ran B.C. transit systems without serious accident for 64 years until taken over by the province.

* * * * *

Last Sunday, the Old Cemeteries Society hosted a tour of Point Ellice bridge victims in Ross Bay Cemetery. There are several markers; some are expensive and imposing, some are modest and at least one is unmarked. The tour included streetcar conductors and the City’s chief engineer who’d claimed that, too busy to inspect Point Ellice bridge himself, he’d left it to junior staff. He kept his job until retirement.

It’s likely that the City of Victoria had to pick up the tab for one or two of the headstones; at least they didn’t place victims, anonymously, in Potter’s Field, as was the usual practice of the day for indigents who imposed upon municipal benevolence.

Left: “In memory of Francis T. James, died May 26, 1896, aged 44 years.” Middle: The marker for Capt. William Grant and family; victims of the Point Ellice bridge collapse, living and dead, were laid out on Grant’s lawn. Right: “Alberta Amelia, aged 5 years.”—Author’s Collection

* * * * *

Years later, when writing a series of reminiscent articles in the Colonist that became two books, former editor and owner D.W. Higgins made a single passing comment on the Point Ellice bridge disaster. It seems a curious remark given that he’d been a major shareholder in the streetcar company.

A fortune teller had assured him of the coming holiday weekend, “You will have glorious weather and a good time.”

Wrote Higgins: “Not a word about a defective bridge which even then was tottering to its fall. A word of warning from the medium might have caused an inspection to be made, and been the means of saving 56 [sic] precious lives, for within 48 hours after the ‘good time’ was promised by the medium two-score homes were desolate...”