‘In Ever Loving Memory of Molly Justice’

My Aunt Ada, left, and her best friend and neighbour, Molly Justice, in front of the Duke residence, 870 Brett Ave., Saanich. She looks very much a young woman in this photo, but Molly was only 15 when she was murdered on the CN Railway tracks, within two blocks of her home in 1943. —Family photo

On the 70th anniversary of her death Jennifer and I placed this crude memorial to Molly at or near where she died. We intend to make another pilgrimage this week for the 80th anniversary.

* * * * *

I’ve always felt that I grew up with Molly Justice, that she was family even though we weren’t related and she was gone before I was born.

Nevertheless, she is part of my DNA.

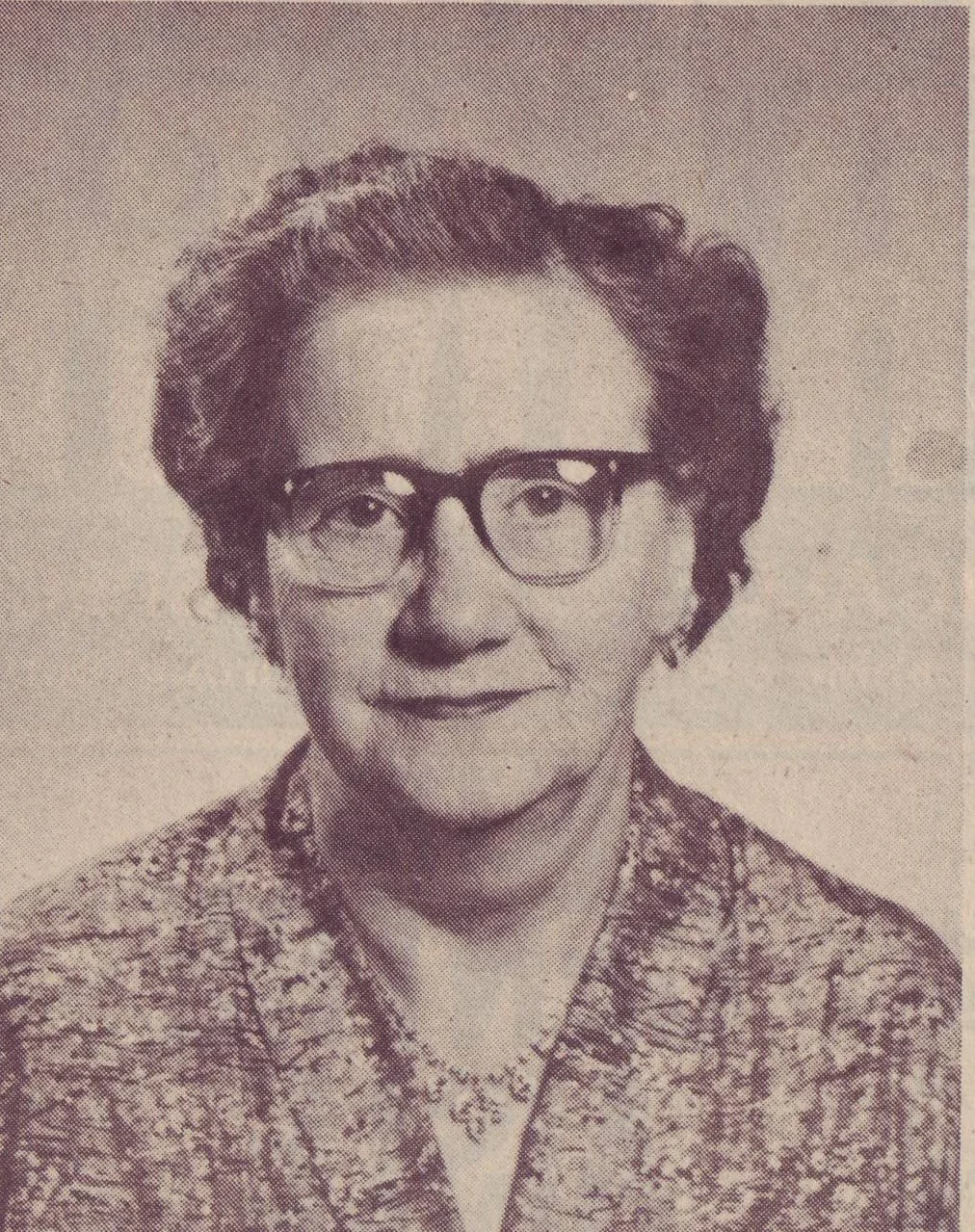

Newspaper photo of Molly Justice.

My Aunt Ada’s best friend, she’d lived one house down and across the road from our home on Brett Avenue, just east of Swan Lake, in Saanich. Ada and Uncle Cec lived next door to us; Ada was expecting when Molly Justice died and named her daughter, my cousin Molly, for her.

This January 18th will be the 80th anniversary of Molly Justice’s murder beside the railway tracks, within minutes of reaching her home.

Ten years ago, for the 70th anniversary, Jennifer and I made the trip to my childhood stomping grounds of Saanich to pay homage to Molly by attaching a poster to a tree beside the former CN Railway tracks, what’s now the Lochside Regional Trail, where her mutilated body was found in January 1943.

As the photo shows it was simple, even crude, but heart-felt.

It was my way of keeping alive a family tradition. For over 40 years until her death, my grandmother, Ellen Green, placed an In Memoriam ad in the Victoria Colonist: “In ever loving memory of Molly Justice, taken from us...”

I’ve told the story of Molly Justice several times over the years but not here in the Chronicles and it has recently been retold in a book on unsolved B.C. crimes. In answer to a Times Colonist reporter several years ago, when he asked me whether I thought there was merit in their printing yet another story on Molly, I replied that I’d prefer that Molly Justice be remembered as a murder victim than that she be a murder victim and forgotten.

So I tell her story again in this week’s Chronicles. 100’s have responded to my promo on Facebook over the past week and I’ve received numerous emails and letters over the years in response to my mentions of Molly, in print and online.

I shall continue to do my small part in keeping her memory alive for as long as I’m able.

* * * * *

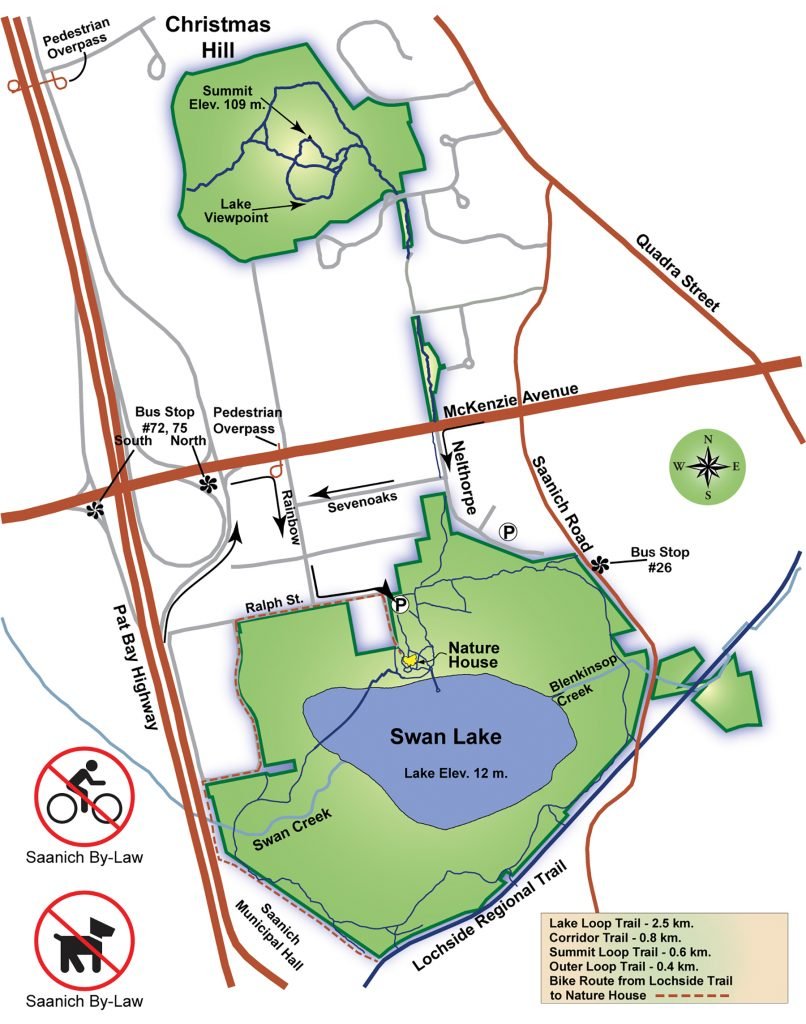

Unfortunately, this map doesn’t show Vernon and Darwin roads, Leslie Drive or Brett Ave., but it does show how close the present Saanich Municipal Hall is to where Molly was murdered. The junction of Saanich Road and Douglas Street (the Island Highway) and site of the Uptown Mall, is just to the bottom left. —Swan Lake Christmas Hill Nature Sanctuary

As noted, I grew up with Molly Justice’s slaying although it happened before I was born.

But she was part of my family lore. How many times had I heard mention of her by my parents, aunts and uncles, how many times had I walked, wide-eyed, past the very spot where she bled to death, how many times had I begged for the gory details?

But I’d had to wait until I was thought to be old enough for the answers, as unsatisfying as they proved to be. There were suspicions and rumours but much about her killing remains unexplained these 80 years later.

My grandmother remembered Molly Justice every January until she died.

Granny (Ellen) Green’s passport photo. —Family photo

For my grandmother Ellen Green the heartache only ended with her own death in 1989. Even after Molly’s own parents were gone, Grannie kept the faith.

Every January she placed a small In Memoriam notice in the Victoria Colonist:

“JUSTICE–In ever loving memory of Molly who was taken from us…years ago today, 18th January. Gone but will never be forgotten. Always remembered by Mrs. Tom Green, RR1, Parksville, Vancouver Island.”

“I said I would put it in as long as I live and I will,” she told Colonist reporter Ted Shackleford in 1964. “She lived opposite us when we were in Victoria. She was my youngest daughter’s best friend. A finer girl you couldn’t meet anywhere…”

* * * * *

Snow was threatening when 15-year-old Molly Justice stepped from the bus after getting off work, that January evening. It was wartime and stringent ‘dim-out’ regulations forbade any friendly lights to guide her. Although she didn’t like to walk alone at night along the Canadian National Railway grade that passed right by her home, this route was considerably shorter and she invariably used it. Described as being “mature for her age,” her striding figure was observed by the driver as she disappeared into the darkness.

Saanich Police found Molly’s bloodstained body

When next seen, by Saanich Police officers after a couple returning from skating on Swan Lake, reported finding blood-stained parcels, Molly was dead. She lay face down in the snow beside the railway tracks. Her body was yet warm despite her coat and skirt having been pulled up over her head. She’d been struck twice on the head by a heavy object and stabbed as many as 20 times with a small knife.

One thumb had been almost severed by the downward slash of the blade but the cause of death was from loss of blood from her throat wounds. Scuff-marks in the snow showed that she’d fought for her life. Her purse, known to contain $4, and her ring were missing, and she hadn’t been sexually assaulted.

Saanich, Victoria and Provincial Police, assisted by the army Provost Corps (this was wartime), were frustrated by the snow which they thought covered up other clues.

They confirmed that Molly, head seamstress at the General Warehouse Ltd. despite her youth, had caught the 5:50 p.m. bus as usual and got off at Carey Road, walked along University Street to Douglas, then to Vernon and down the embankment at the bridge to the CNR grade. She was attacked at the next crossing, where the tracks crossed Darwin Road.

(If you follow Molly’s route today there simply is no comparison. From Carey Road where she got off the bus, what were commercial greenhouses then country lanes, only an occasional house, long stretches of bush, swamp and darkness, are now a shopping centre, multi-housing and lights—lights everywhere.

(I walked this stretch many a time as a kid and teenager, almost always with company. To think that Molly set out for home alone along this lonely stretch of railway track...

(Her alternative would have been to get off the bus at Douglas and Saanich Road then walk along Saanich for five long blocks. Even that way was dark and lonely when I was a kid, years after Molly’s murder, going home from Sea Cadets.—TW)

The case received international attention when Victoria Mayor Andrew McGavin publicly protested to Premier John Hart of other incidents of girls being molested as a direct result of the dim-out. No lights after dark had been initiated at the request of American military authorities although neither Port Angeles nor Honolulu were so restricted.

A check of clothing and dry-cleaning shops turned up some bloodied garments but these proved to be unconnected to the case. Unwilling to wait longer, police attempted to melt the snow, now a foot deep at the death scene, with hot water, but quickly stopped lest they destroy invaluable evidence.

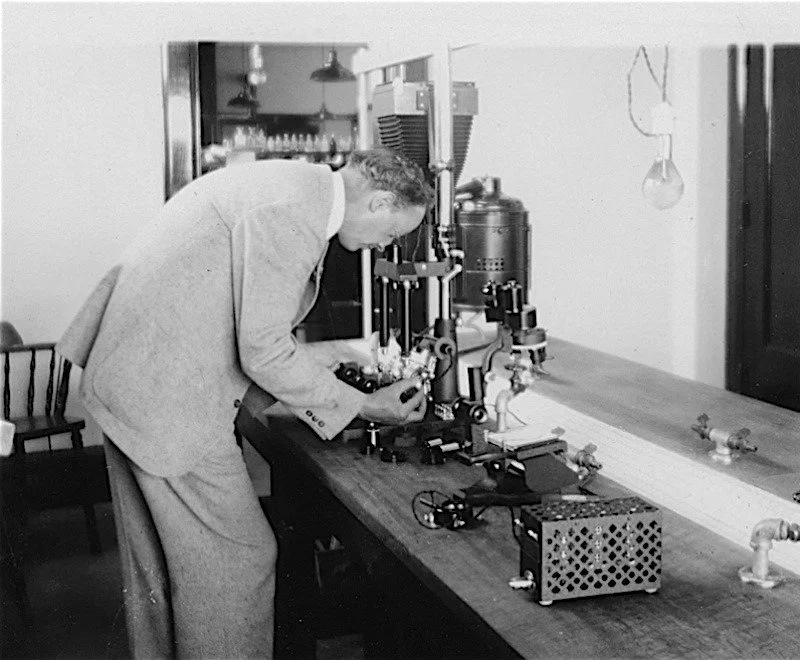

Inspector John F.C.B. Vance, renowned forensic scientist for the Vancouver City Police, was called in. At the request of Saanich Police he was asked to eliminate family members as suspects by giving each of them a blood test. None of them matched the blood samples taken from under Molly’s fingernails.

Vancouver Insp. John Vance was called in to assist in the investigation of Molly’s murder. —Eve Lazarus, Blood, Sweat and Fear

A doubling of the $250 reward for information offered by Saanich Municipality drew no response.

The inquest, personally attended by Attorney-General R.L. Maitland, drew 50 spectators. It took Dr. J.H. Moore several minutes to list the wounds suffered by Molly in her struggle with her killer.

On February 4th, Molly’s purse and a cigarette lighter bearing the initials R.L. were found under an inverted bucket beside Swan Lake. No fingerprints were lifted from either article. Then police, who’d widened their search over 60 acres, also found a pair of men’s gloves, the right one bloodstained, but not sufficiently to yield a blood type.

Of soft Capeskin, tan in colour, with full lining and close-fitting elastic wrists encircled by two coloured bands, 96 pairs had been sold in the area between October and December 1942. It took 1700 interviews to clear the first 30 pairs of gloves and, by early March, 81 had been accounted for.

Youthful suspect arrested.

On May 16th, a youth whose name was withheld, was arrested and charged with threatening a girl near Swan Lake with “the same as Molly Justice got” if she continued to resist his advances. Acting upon information provided by this suspect whose name was not released, 50-year-old logger William Mitchell was charged with the murder of Molly Justice.

But then a mysterious veil of silence descended upon the case. There was speculation that a prominent British Columbia family was involved and that ‘politics’ were covering up for them. Other rumours hinted at an unnatural relationship between two principals in the case. Newspapers stopped covering the story. Mitchell was acquitted for lack of evidence.

Police were convinced that the killer knew Molly.

They were sure that he was familiar with her habits and had targeted her. She’d been staying with friends and was returning home after work that evening. Police, rejecting Molly’s attack as a crime of opportunity, were convinced that he’d known that she’d come along the railway tracks and had waited for her.

In 1964, as Colonist copyboy bucking for cub reporter, and inspired by a lifetime of family gossip, I set out to examine the 21-year-old case. Saanich Police Sgt. Eric Elwell, present when they found the body, wouldn’t discuss it with me after first agreeing to. Another investigating officer “couldn’t remember”. Saanich Police Chief Bert Pearson, whose office in the then-new Saanich Municipal Hall overlooked the murder scene—I could clearly see it from where I stood in his doorway—brushed me off.

The files, because the case remained unsolved, were closed to the public.

What had been lonely bush in 1943 had mostly given way to a residential area. The exact spot where Molly bled to death from multiple stab wounds is now a front yard.*

*(I’ve been given two locations, by my mother and the late Pete Oliver. Mom said she was found immediately southeast of the junction of the CNR and Darwin Road. Pete said the murder site was several 100 feet to the north and west, directly opposite the family home which is still there.)

Molly, whose parents were gone, began to retreat into the mists of history.

But not for my maternal grandmother Ellen Green, who never forgot the attractive, likeable 15-year-old girl whose brutal death had, it seemed, been allowed to go unsolved and unresolved.

When a brief story appeared in the Colonist on the 20th anniversary of Molly’s murder, it drew a letter from a woman resident of San Francisco who’d been in Victoria at the time. In part it reads: “…I have never forgotten her, and never will; maybe it is because her name was ‘Justice.’ So, as always, I pray for the soul of Molly and hope one day she will meet with ‘Justice’ concerning her death….”

‘Justice’ for Molly Justice was late in coming.

In a way, Molly did finally receive the justice originally denied her. Not the nice and neat, tied-with-a-ribbon kind we like in our fiction, but justice of sorts.

Late in 1967, Saanich Police charged a 40-year-old Port Alberni man, Frank Hulbert, aka Frank Pepler, with having given false testimony as a youth at William Mitchell’s trial. Two years later, Hulbert was convicted of perjury and sentenced to five years’ imprisonment.

During a second trial in January 1969, his first conviction having been overturned on grounds of an error in direction by the judge, former City of Victoria policeman Lewis T. Kamann testified that Hulbert had admitted to him, in 1947 or ‘48, that he’d killed Molly–and defied Kamann to prove it.

In March 1996, the month following Francis James Pepler’s death, aged 68, Saanich Insp. Al Hickman reopened the 53-year-old case at the request of Molly’s sister-in-law, Marjorie Justice.

He identified the killer as Frank Pepler, who was 15 at the time of the murder and stepson to Eric Pepler, British Columbia attorney general for 20 years who, he charged, had intervened personally in the murder case and that of a sexual assault on an 11-year-old girl, four months later.

Hulbert had been given an indefinite sentence ‘for an unnamed charge’ under the Juvenile Delinquent Act and shipped off to the Industrial School for Boys on the Mainland. He also served time at Oakalla Penitentiary.

Saanich police had repeatedly tried to lay a murder charge against Hulbert/Pepler through the 1960’s but Crown prosecutors thought too much time had passed and investigators had to settle for the upheld perjury conviction and a four and a-half year sentence.

In September 1996, it was reported that “An investigation into the case of 15-year-old Molly Justice, murdered 53 years ago in Saanich, has found no evidence of a cover-up, Attorney General Ujjal Dosanjh said today in releasing the 147-page report of the investigation...”

Molly’s case had been reopened by the Attorney General’s office “to examine this case from another era because of continuing public concern over possible injustices in how the matter was handled at the time,” said Dosanjh. At issue was Hulbert/Pepler’s familial link to Deputy AG Eric Pepler who, many believe to this day, interfered in the investigation by having his stepson shuttled off the local stage as a juvenile offender rather than be charged and tried for Molly’s murder.

Dosanjjh termed some of the report’s conclusions to be shocking and unacceptable, and assured the public that it would ”extremely unlikely” that the justice system of today would permit the AG’s office to interfere or to override a decision to prosecute by the criminal justice branch (i.e. Crown prosecutors).

Suspected murderer died ‘peacefully’.

Just months before, Hulbert/Pepler, the alleged killer, ended his life as a recluse, living in a converted bus. He died ‘peacefully,’ according to his obituary.

A damn sight more peacefully than did 15-year-old Molly Justice, that snowy evening beside the railway tracks in January 1943. If he suffered any remorse over those 53 years it can’t have been any greater than the heartache suffered by my grandmother who went to her own grave without seeing the case resolved.

Granny was loyal right up until that last January 18th of 1989 with her ad, “JUSTICE–In ever loving memory of Molly…”

Hence, in January 2013, and again in January 2023, my pilgrimage to the former the CN Railway tracks (now the Lochside Regional Trail) to place a notice at or near where Molly died, 80 years ago. It isn’t much, just a laminated poster and some plastic flowers—but better that than Molly Justice not be remembered on these 10th anniversaries of her brutal murder.