In the Shadow of Greatness

From the man who brought us those memorable eccentrics, Messrs. David Copperfield, Oliver Twist, Barnaby Rudge, Mr. Pickwick and Company—there came to Victoria in 1868 the slight figure, in flesh and in fact, of one Acting Lieut. Sydney Smith Haldimand Dickens, RN.

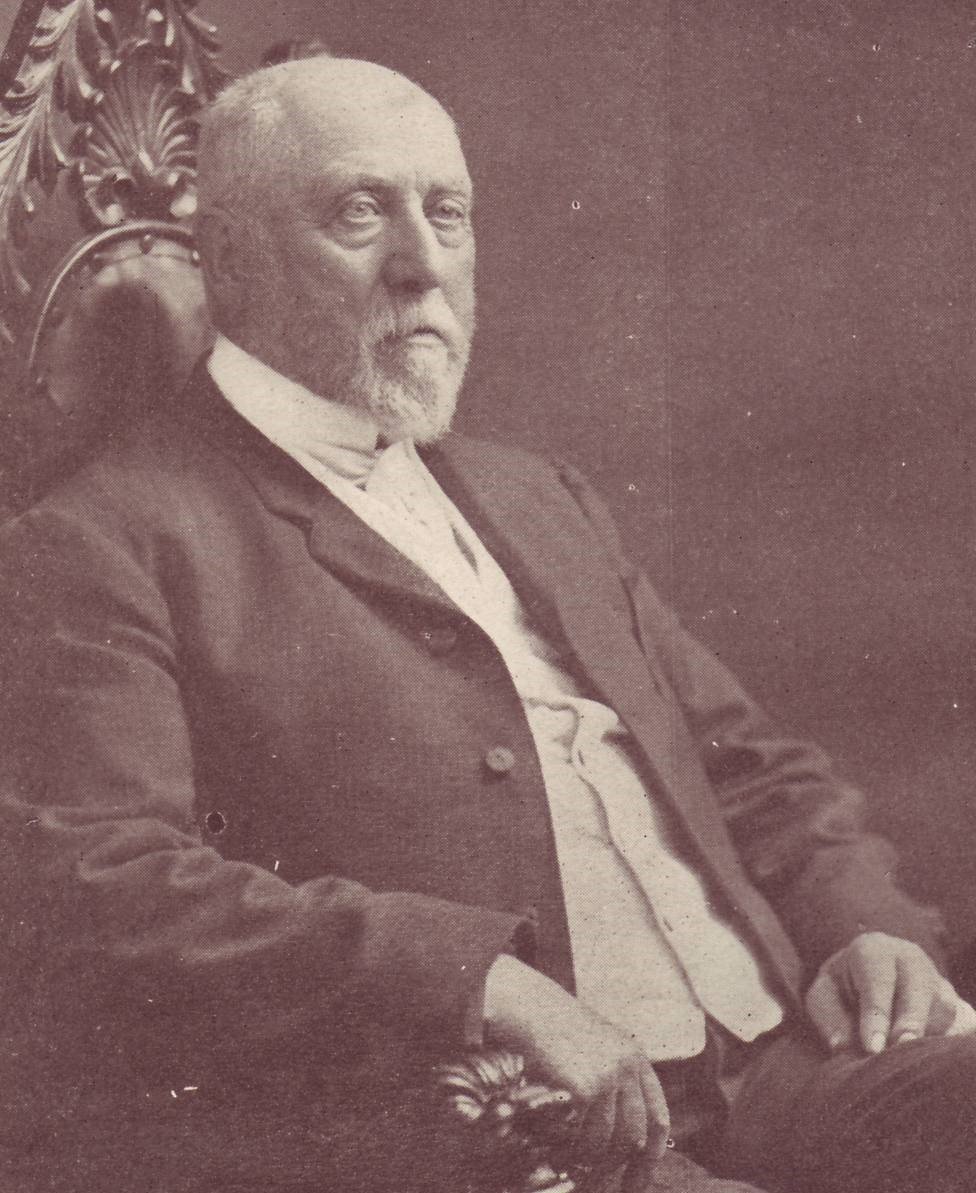

A very young Sydney Dickens.—Wikipedia

For those unacquainted with the literary classics, this junior officer of Her Majesty’s Royal Navy was the fifth son of no less a personage than Charles Dickens, celebrated novelist.

Or, as young Sydney became known to Victorians, if ever so briefly, ‘Vindicator.’

As the son of the greatest novelist of the day, much was expected of young Sydney. Was he up to it? Did he inherit his father’s strength of character and abilities? Or, as so often seems to be the case of a scion of fame and fortune, was he all but doomed to live in his father’s shadow?

* * * * *

Twenty-one when he arrived in Esquimalt, Sydney was said to have been “a born little sailor” who early on earned his father’s esteem as “The Admiral” and “The Ocean Spectre,” the latter appellation because his eyes seemed to be too big for his small, fragile body. Frail or not—at age 13 he was just three feet tall—he was off to Brackenbury’s Military School in Wimbledon.

A year later, he joined the Royal Navy as a cadet on the training ship Britannia, then a subsequent posting to HMS Orlando.

But not all went well. Two years after becoming a midshipman (a “young gentleman” in training to become an officer) he was docked a year’s seniority for unspecified “misconduct”. He managed to regain his superiors’ respect, however, and his punishment was shortened to just four months. He was promoted to acting sub-lieutenant in August 1867, then acting lieutenant the following year.

By April 1868, when our story begins, he was serving aboard the naval cutter HMS Scout.

* * * * *

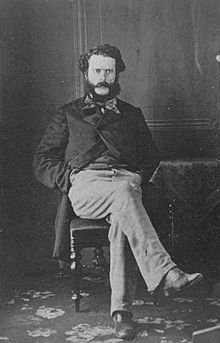

Journalist D.W. Higgins. —Author’s Collection

The story behind this forgotten chapter of our past began on a beautiful spring morning in April as pioneer journalist D.W. Higgins enjoyed his constitutional by walking to the post office. As he lived in Victoria and the post office was situated in Esquimalt, this meant a round trip of something like eight miles.

It had been as Higgins strolled along that he noticed a young naval officer attempting to drag a drunken sailor, who was sprawled unconscious in the middle of the road, from the path of oncoming traffic. Upon Higgins assisting in this unceremonious act of mercy, the two had exchanged cards, the journalist reading: “Sydney Dickens, HMS Scout.”

Higgins’ memory failed him here; the record shows that Dickens was serving on the screw corvette HMS Pylades at the time, not the Scout. —Wikipedia

In appearance, Higgins wrote years afterwards, the young officer was “rather insignificant. He was short and spare, but what he lacked in height and bulk, he made up for in dignity....”

Upon glancing at the other's card, Higgins remarked on the weather and scenery then, out of curiosity, asked his new-found acquaintance if he was related to Charles Dickens, the novelist. Much to his amazement, the officer replied that he was in fact, Dickens’ youngest son, and asked if Higgins had ever met the great author.

“Unfortunately, no,” replied Higgins, “but I am leaving in a few days for the East, where I hope to hear him read. He is now in the Eastern States, and I have timed my departure hence so as to attend at least one of his readings.”

Obviously pleased by Higgins’ regard for his father, the younger Dickens offered to give him a letter of introduction. The following day, at his office, Higgins received “a very prettily worded note from Sub-Lieut. Dickens and the promised letter of introduction”.

As It happened, however, Higgins was unable to get away as planned and, after a long, unpleasant voyage to San Francisco, he boarded another vessel for Panama where he encountered a further delay. As a result, by the time he arrived in New York, Dickens, then conducting an American speaking tour, had been forced by ill-health to cancel the remainder of his tour and return to England.

“My disappointment was great,” Higgins wrote almost 40 years later, “and I was destined never to experience the gratification of meeting this illustrious and truly great writer and novelist.”

Long after Dickens’ shorted transatlantic tour, Higgins read a book by Dickens’ former manager who revealed that the illustrious author had been plagued throughout the trip by illness, exhaustion and alcoohol; in fact, Higgins sighed, the ill-starred tour had been, “from first to last, one great puzzle”.

Only two years after, Dickens was dead. and Higgins, half a world away in outpost Victoria, never got to see, hear or meet his literary idol.

Upon his return to Victoria he’d found that Sydney Dickens, since promoted to full lieutenant, was still stationed at Esquimalt. In his role of journalist, Higgins was privy to all manner of information and in the course of duty, he heard rumours to the effect that Young Dickens's promotion had caused ill-feeling among fellow officers.

“I'd rather be a son of Charles Dickens,” one captain was overheard to remark, “than the heir of the Duke of Westminster when promotions are about.”

Professionally and socially, Higgins met Dickens on several occasions; particularly as both were frequent guests of Rear Admiral George F. Hastings, CB and his attractive wife at Hazlehurst House, overlooking Esquimalt Harbour, and within a stone’s throw of the flagship [HMS Zealous] as she lay at anchor.”

Admiral George Hastings and his flagship, HMS Zealous. —BC Archives

During this period, the Admiral found himself facing the threat of an invasion of Vancouver Island by the Fenians (see: “The Finians!” Was the Cry), an American-based “army” of Irishman fighting for the independence of their homeland.

“There was much talk of [an] invasion in 1868 and 1869,” Higgins explained, “and the Admiral was so much impressed by the information that appeared from time to time in the local papers that he hesitated to leave Esquimalt lest in his absence the Fenians should seize the naval stores and reduce Victoria.

The crisis, real or exaggerated, prompted John Robson, publisher of the New Westminster newspaper, the British Columbian, to editorially rake Admiral Hastings for importing meat and vegetables for the navy from the United States, the Fenian headquarters, rather than from mainland British Columbia suppliers.

New Westminster journalist and, later, politician John Robson got under Admiral Hastings’ skin. —Wikipedia

Hastings, whom Higgins thought to be unduly sensitive to criticism, had merely been honouring the terms of a contract signed by his predecessor.

Stung by Robson's charges, he sent for Lieut. Dickens. Apparently a firm believer of the adage, like father like son, he instructed Dickens to answer Robson in the city press under the pseudonym, “Vindicator.” The patriotic Higgins agreed to publish the rebuttal in the Colonist. Everyone, he wrote, “anticipated a brilliant onslaught from the son of the greatest English writer”.

But, upon receiving the first article, personally delivered to his home by the author, he was stunned by its mediocrity—“it was heavy, dull and laboured; no good points were made”.

Higgins had no choice but to print “Vindicator’s” reply as agreed, then wait in embarrassed silence for the inevitable broadside from the Royal City press. It wasn't long in coming; Robson “ripped [Dickens] argument to pieces and scattered the fragments all over the controversial field”.

Dickens, probably more aware of his literary shortcomings than anyone, made a second half hearted attempt to battle Robinson in print, then retired from the field with the Colombian the undisputed victor.

Alas, Dickens’ humility was compounded by a second disaster on the social front. Although not an expert horseman, he did enjoy riding with the ladies, and volunteered to escort three of them on an excursion to Millstream, then virtually unsettled and with few distinct trails. Not anticipating being out for long, Dickens and company took no food along; an unfortunate oversight as they wandered off the trail.

By dark, they were lost and worried. In desperation (or confusion), they abandoned their mounts and tried to regain the trail on foot. Hours passed without their return and, at 10:00 that night, a large search party armed with lanterns set out from Esquimalt. “They beat the bush until the grey of morning, when they came upon Dickens and two of his fair companions sitting beneath the shadow of a fallen tree and chilled to the bone.

“The other lady in her fright had wandered farther away and was not found till daylight. She was in an awful state, with clothes partly torn off from contact with branches, and she was worn out. With care and attention she soon recovered and was none the worse for the adventure.”

The good ladies stoutly proclaimed Lieut. Dickens' gallantry under fire but demurred from his further invitations to enjoy the great outdoors.

* * * * *

Perhaps because of Admiral Hastings’ disappointment with his literary prowess Dickens’ recent promotion to acting lieutenant was rescinded for a year and a-half. Two years later, he was finally promoted to full lieutenant.

By then he’d fallen heavily into debt—a cardinal sin to English gentry, his father in particular. So reckless had Sydney become with money (this failing and his bumpy naval career hint at psychological problems that we can only guess at) that the senior Dickens not only refused to help him but forbade him entry to the family home.

“I fear Sydney is much too far gone for recovery and I begin to wish he were honestly dead,” Dickens Sr. wrote to other son Henry. (By then Sydney’s sister Mamie had also come to despise him.)

Abandoned by his family, Sidney’s troubles were soon resolved once and for all. Invalided from the navy in April 1872 while serving in India aboard HMS Topaze, he sailed for home aboard a passenger ship, but made it only as far as Aden. There, he died “with the flower of youth and opportunity blossoming about him in the May of his existence,” as Higgins put it. He was buried at sea—just 25 years old.

His naval career on the Pacific Station had been anything but stellar and, more than a century after, Sydney Smith Haldimand Dickens, the fifth and youngest son of the great Charles Dickens, is best remembered for the journalistic duel that ended with a whimper.

* * * * *

NWMP Insp. Francis Dickens, 1884. —Wikipedia

Sydney isn’t the only son of Charles Dickens who came to Canada. His older brother, Francis Jeffrey, became an inspector in the North-West Mounted Police. Somewhat a tragic figure like Sydney, Francis’ Canadian career has earned mixed reviews from historians and popular writers, ranging from respect to ridicule.

Fortunately for Francis, his friends chose to address him as Frank rather than his father’s less kindly “Chickenstalker,” inspired by a character in one of Dickens’ novels. Schooled in Germany with the original intent of becoming a doctor, he switched course to join the Bengal Mounted Police. After seven years in India and squandering his inheritance, his aunt Georgina Hogarth used her influence with Lord Dufferin, then no less than the governor general of Canada, to get him a commission as a sub-inspector in the NWMP.

This was just after the newly-created, 300-man force’s famous “March West”.

Francis Dickens joined the famous NWMP too late for the legendary (and almost disastrous) March West, depicted here by the famous Canadian illustrator, C. W.Jefferys. —www.cwjefferys.ca/

Over the next 12 years he served at Forts Walsh, McLeod and Pitt, was promoted to inspector in 1880, and gained dubious distinction for his defence of Fort Pitt during the 1885 North-West Rebellion. He has been blamed, unfairly it seems, for ordering the fort’s evacuation in the face of overpowering odds—10 to one.

Two years later he, like brother Sydney, had serious heath issues which included increasing deafness, and he took early discharge from the Mounties. He was on the verge of giving a lecture tour in the U.S. when, jusst 42, he suffered a fatal heart attack.

Like Sydney, he’d been unable to handle money, being always in debt. Upon asking his father to lend him money and buy him a horse and gun so he could take up farming, Charles sneeringly told a friend that he’d only be robbed, thrown from the horse and accidentally shoot himself.

Some historians have been equally rude, having accused him of “drunkenness, laziness and recklessness”. All three charges have been contested by others.

Vancouver humorist Eric Nicol was downright cruel, writing a satirical book that’s supposedly composed of letters written by Francis Dickens. People have come to accept Nicol’s work of fiction as the real thing, and in several plays and novels his name or character has also been used unsympathetically. As a result, he’s seen to be a buffoon.

As if Charles Dickens’ sons, Sydney and Francis, didn’t have to shoulder enough of a load in their lonely travels through life while in the shadow of one of the most renowned men of his age. Simply put, they couldn’t hope to live up to peoples’ expectations of them.

* * * * *

I noted earlier that Sydney’s naval career on the Pacific Station was anything but stellar and, more than a century after, the fifth and youngest son of the great Charles Dickens, is best remembered for the journalistic duel that ended with a whimper. Perhaps so, but he hasn’t been totally forgotten; in fact, he’s been immortalized on our provincial maps with Dickens Point, south of Stopford Point on the southeast side of Portland Canal, northwest of the mouth of the Nass River, Cassiar Land District.

Like the man himself, it’s hardly distinguishable.

Master cartographer and historian Capt. John T. Walbran explains his having been so honoured: “At a theatrical performance and ball given at Victoria 29 December 1868 by Rear Admiral Hastings, Dickens was one of the principal actors, and the Victoria Colonist 31 December 1868 has a long account of the entertainment, and favourably mentions Dickens' performance in the play called ‘The Steeple Chase; or in the Pigskin.’

“Lieutenant Stopford, of [HMS] Zealous, and Mr. Brodie, of the [S.S.] Beaver, also acted. Dickens and Stopford Points are close together. Named in 1869 by staff commander [Capt. George Pender, HM hired surveying vessel Beaver (who was doubtless at the play)."