Is Historic John Tod House Haunted?

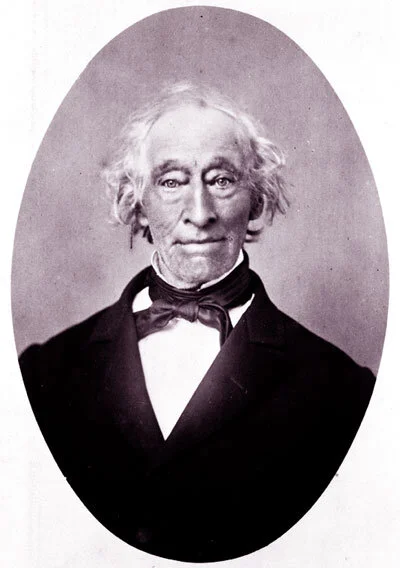

Canada’s oldest house west of the Great Lakes, built in Oak Bay by Hudson’s Bay Company chief factor John Tod, is better known for its story of being haunted by a ghost in chains. Photo: www.historicplaces.ca

Before getting down to things that go bump in the night I must introduce you to Hudson’s Bay. Co. fur trader John Tod. Not only was he one of a kind but so is this unique description of him by the gilt-penned historian Hubert Bancroft:

“Above a broad, straight Scotch nose and high cheekbones were glittering grey eyes which flashed perpetual fun and intelligence. And the mouth! Support me, O my muse! What an opening for gin and eloquence.

“Had the mouth been small, the mighty brain above it would have burst; as it was, the stream of communication, once set flowing, every limb and fibre of the body talked, the blazing eyes, the electrified hair and the well-poised tongue all dancing attendance.

“Tod could no more tell his story seated in a chair than he could fly to Jupiter while chained to the Rock of Gibraltar; arms, legs and vertebrae were all brought into requisition while high-hued information, bombed with broad oaths, burst from his brain like lava from Etna.

“But although not among earth’s pretty ones, among the starched and veneered of broadways and boulevards, his angular contour and disjointed gait presented anything but an imposing appearance, yet John Tod was built a man from the ground upward, and those with eyes might see in him a king, aye, every inch a king.”

Whew and wow! (They don’t write biographies like this any more...)

After such an eloquent description, you might wonder what more could I possibly say about John Tod, fur trader and character? A remarkable man was this pioneer who’s remembered for, among other things, having saved Fort Kamloops from attack, armed with only a scalpel.

Tod had ridden straight into a war party and told them that dreaded smallpox had broken out in the fort. Suddenly panic-stricken, the warriors dropped their weapons and lined up for him to vaccinate them with his surgical knife. That done, the daring Scot advised his patients to keep their arms in slings—and the danger of attack was averted!

Such are the legends told of this Hudson’s Bay Co. trader born about 1793, who joined the fur company as a teenage apprentice and who became a chief factor at age 40. His early years were served in eastern Canada, the greater part of an exciting career being spent in New Caledonia (British Columbia). He retired to his home in Oak Bay, today an upper-scale Victoria suburb, at age 58. Appointed to the Legislative Council of Vancouver Island, he helped to organize the construction of the first school, became a firm advocate of Confederation and a justice of the peace. He died, wealthy greatly respected, in 1882.

During his final years Tod indulged in writing letters, reading, studying religion, following economic and political developments, and occasionally enjoying such outdoor excursions as “strolling on the sea-beaten shores, and about the rocks and boulders, picking up fossilized specimens of the antediluvian worlds”. He also found time to oversee a successful farm.

John Tod left 10 children and $35,000, then a very substantial sum.

Saanich Inlet’s Tod Inlet and Tod Creek in Victoria’s Highlands district honour this colourful pioneer, as does Tod Mountain near Kamloops. Mary Tod Island, just offshore of the former Tod estate, recalls a daughter. It’s local legend that the wily older fur trader had a tunnel connecting the island and the shore, for reasons which we can only guess at. Today, Tod House is a publicly owned heritage site.

But John Tod’s story didn’t end with his passing in 1882. His house—“the oldest, still standing dwelling west of the great Lakes”—is said to be haunted. So much so that it has repeatedly made national newspaper headlines. In 1944, Mrs. E.C. Turner who’d lived in it for 15 years, said she’d had enough: “I’ve...loved the place, but I would never go back. Something dogged my every footstep.”

In January 1947 Victoria Daily Times reporter Humphrey Davy interviewed Tod House owner of two years, Lt.-Col. T.C. Evans, who admitted that he and several guests (Mrs. J. Murray, Mrs. H.T. Goodland and Col. and Mrs. Charles King) were “puzzled” by some strange occurrences. On New Year’s Eve, they’d all been in an older part of the house where stood an antique dutch cupboard. Twenty minutes before midnight, all became aware that an old biscuit box hooked to the cupboard “was swinging violently for no apparent reason”. By then Evans had become almost used to the old home’s idiosyncrasies so he tried to laugh off the antics of the biscuit box. And he refuted a suggestion that, on New Year’s Eve, people are inclined to see things.

Evans told of Christmas cards and fir boughs hung about the living room being found piled in the middle of the floor; of a rocking chair that insisted upon rocking by itself until he became so annoyed that he got rid of it; of the door latch to the basement that continued to open on its own even after he tried to secure it. Other phenomena included hats thrown about and slamming doors. He admitted that the guest room wasn’t popular with visitors who were always the first to rise in the morning and eager to take their leave.

Neither he nor his wife were unnerved by any of this

As he explained, “I’m a materialist. I don’t believe in ghosts and it doesn’t bother my wife.” Mrs. Evans thought there was more reason to fear the living—and newspaper reporters—than the dead.

Evans did express his annoyance with one recurring phenomenon: “See that window over there? For some reason it keeps on breaking on me and I’m dashed if I can find the reason.”

But all of that came to a sudden end in 1952 when he hired some workmen to install an oil tank under the lawn. They left him to finish the job himself when they unearthed human bones which he said were those of “a man who must have been dead for about 50 years. The bones looked as if they had been sprinkled with lime.” (Readers take note—we’ll come back to the skeleton’s progeny later.—TW)

Evans said he’d made improvements to the house whose foundation had been in bad repair when he bought it—against the urging of an anonymous telephone caller who warned him that the house was haunted.

When Davy asked B.C. Provincial Archives staff about previous reports of haunted happenings in Tod House, they replied they were only interested in history, not ghosts.

Davy also noted there were six chimneys in the house, one of which had been bricked up. And there was still a bullet hole (meant for Tod) in the front door. Although all the rooms other than the kitchen had good overhead, the doors are lower, making many visitors duck their heads, and the floors slope.

Davy’s report prompted a follow-up in the Vancouver Sun by reporter Ted Greenslade who plowed the same ground then speculated that the ghost was either “the old man of mystery,” John Tod, or “one of his sweethearts”. After noting how some guests had bolted from the accursed guest room during the night without waiting to say goodbye to their hosts in the morning, he termed the kitchen with its door to the cellar to be the epi-centre of ghostly activities.

“To look at, it is a very ordinary board door with a regular old press down latch fitting into a slot in the jamb. The unique thing about it is that this door regularly opens all by itself. Now, if it were merely a matter of the catch slipping out of the groove, and the door swinging open, it would be easy to explain, but it is nothing quite so simple. On the occasions when the door opens, the bar which goes through the wood can be seen moving up and lifting the catch bar out of its slot at the same speed at which it would operate if a human being were coming into the room...”

Prominent Victoria journalist and historian James K. Nesbitt went into greater detail in the Vancouver News-Herald when he wrote of human bones being dug up under the lawn of a “quaint cottage” on Heron Street which had become a “rubber-necking” target of amateur psychic sleuths. Its owner [Col. Evans], he wrote, had become the recipient of unsolicited advice on how to deal with the strange manifestations. One of these “experts” suggested that he leave a writing pad and pen for the ghost to write him a message; another advised that a pail of water “sometimes appeals to people from another world”.

Nesbitt also interviewed former owner for 15 years, Mrs. E.C. Turner, who said there was “always something strange going on in the house” that she couldn’t explain. Sometimes her cat would suddenly growl, arch her back and her hair would stand up on end. “I feel sure, even now, that the cat saw something, or somebody, that I couldn’t see.

“Sometimes when I walked along the passage [hallway] I felt there was someone walking behind me. It got to be very tiresome.

“And, too, sometimes I would awake at night feeling a presence, and the door would slowly open. I was totally convinced there was a presence, though I couldn’t see it. I loved the old house, though I wouldn’t like to go back. I felt the presence—there was no question of that.”

Col. Evans had had to install a bolt on the door leading from the kitchen to the cellar to stop its latch opening on its own. On the bright side, Mrs. Evans almost welcomed the company of their invisible tenant: “[I’m] never lonely in the house, with these invisible personages around. I don’t ever feel I’m alone.”

That said, even the Evanses refused to sleep in their guest room which had been avoided by former owner Mrs. Turner and her daughter and where two RCAF guests reported that they were awakened in the night by the sounds of “people walking about the house”. (We’ll come back to this, too.—TW)

Nesbitt concluded with the belief of one unidentified psychic phenomena expert who thought that “someone in the far distant past, probably one of Tod’s wives, was not happy in that house and that the spirit has returned to find some of the happiness it missed”.

The clippings go on. In 1949 the Colonist’s Barnett McKinley, after acknowledging Tod House’s widespread fame, wrote of how “the atmosphere of the place takes hold of you. You feel that you are definitely approaching a spot where history has mellowed the scene.

“The low front door...with its circular fanlight; the narrow, faintly coloured casement panes at the front, the generous bay windows at the side of the building, all speak of an age when workmanship was solid art and homes were built for large families—and ghosts.”

He went on to describe the low ceilings, open, hand-hewn split timber beams, and a kitchen that one would naturally associate with movie “thrillers.” None of the modern conveniences and renovations concealed the fact that this was an old home of “many memories from bygone days”.

McKinley mentioned an unnamed former resident who, as a young boy, received a whipping from his mother for telling neighbours of ghostly activities in the house. He recites the incident of Christmas holly decorations (Col. Evans said fir boughs) being thrown about, the swinging biscuit “barrel” (not box) and the door to the cellar being unlatched and opened even as a member of the household watched. All these incidents occurred at night and were more frequent in the last months of the year.

He then tells of the excavation for an oil tank and the discovery, at the five-foot-level, of human remains and of their being identified by an anatomist who said they’d been buried in lime. There was no skull but he was sure the deceased was “an Oriental”. Since then spiritual and worldly peace had reigned in Tod House although an anonymous spiritualist had warned Col. Evans that it was but a lull before the storm.

February 1950: a short article “special to the Vancouver Sun” made what appears to be the first reference to two airmen whose sleep in the guest room was disturbed by a woman in chains who appeared to be pleading with them.

An article in the Times, December 1951(?—my photocopy from the B.C. Provincial Archives is hard to read) has as its provocative subhead, “Door Opened, Chair Rocked,” and was the third article in a series on “spiritualism” by Ron Baird.

Of all the instances of psychic phenomena on the North American continent recorded over the previous 100 years, so Baird claimed, one of the strangest cases of all was that of John Tod House, 2564 Heron Street, Oak Bay.

According to Baird, Tod had a Native woman as housekeeper who doubled, he implies, as Tod’s common law wife until he returned from a visit to Scotland with a legal (and white) bride. At this the housekeeper, who’d become mentally unhinged by jealousy, “disappeared”. Baird then proceeds to recite many of the remarkable occurrences that past and present owners of Tod House had witnessed over the years:

A cookie jar swinging on a hook without aid of human forces

An antique rocking chair moving back and forth as though someone were sitting in it

The old-style, lift-up latch on the basement door opening of its own free will and leaving the door ajar (investigation revealed that considerable pressure was needed to lift the latch)

Hats and coats on hooks in a hall closet thrown on the floor

Christmas cards and evergreen boughs hung as decorations piled neatly in the centre of the room on Christmas Day

The two airmen overnight guests mentioned earlier, one of whom was awakened by a woman in chains

Which brings us to the story of these two unnamed airmen who said that one night in Tod house guest room was enough for them. Awakened by what he thought to be the rattling of chains, one of them recalled: “Over in a corner of the room stood an Indian woman, her hands held out to me in such a manner that she seemed to be pleading for help. On her arms and legs were what looked like iron fetters. She kept looking at me, her hands outstretched, and she was saying something I was unable to catch. As suddenly as she appeared, the figure vanished.”

This sensational (but unaccredited) report of a chained ghost drew requests from afar from psychic phenomena investigators wanting to visit Tod House but Mrs. Turner had turned them away, not wanting further notoriety. All these mysterious happenings had ended with the unearthing of the human remains in 1952 according to Col. Evans.

He told reporter Humphrey Davy that the skeleton was that of an Asian man and had been in the ground about 50 years. Many believe, however, a more dramatic version: that the remains were those of an Indigenous woman and linked her to the housekeeper who’d gone mad and, it’s claimed, was kept chained in the cellar.

Unfortunately, the bones disintegrated when exposed to air, he said.

Despite some so-called psychics having predicted that the ghost would return “more violent than ever,” Col. Evans told another Colonist reporter that all unexplained phenomena had in fact ceased. It’s to be noted that he and Mrs. Evans had bought and partially modernized the house well knowing its reputation for ghosts. (The most visible of their upgrades was the large, black-tiled shower stall—just like the kind, other than the colour, the colonel would have been used to in the army.—TW)

Evans concluded, “Some funny things have happened in this house. It abounds in legends,” and he accepted as fact that a “secret passage” had once existed between the house and nearby Willows Beach. The Oak Bay Leader, in January 1961, addressed the legend of a tunnel to Mary Tod Island or Willows Beach by saying that evidence of a tunnel leading to Bowker Creek had in fact been found and that it was alleged historical fact that “Chinese were smuggled into Canada via Bowker Creek.

When next Tod House made the news, nine months later, it was anything but unworldly: Col. Evans had bequeathed his 110-year-old farm house to the British Columbia Historical Society upon his and his wife’s deaths. Having been turned down by the Municipality of Oak Bay, he hoped the old house would become a B.C. historical site. “It will ensure that this great treasure of our past will not be lost as so many others have been,” said BCHS President Mrs. J.E. Godman.

Alas, this generous attempt by the Evanses to make a public ward of the historic house which is now formally designated as a heritage site also fell through and today 254 Heron Street is privately owned and not open to the public.

* * * * *

The news stories go on and on, some of them taking on a life of their own with embellishments, most of them replaying the by now familiar stories of ghostly manifestations, the lady in chains, the skeleton beneath the lawn.

Peace—so far as is known publicly—has reigned at Tod house since the discovery of the skeleton beneath the lawn.

Hudson’s Bay. Co. Chief factor John Tod left 10 children, a small fortune—and a one of British Columbia’s greatest ghost stories. Photo: bcbooklook.com

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.