Jack Fannin, ‘Father’ of the Royal BC Museum

The Royal BC Museum has certainly been in the news lately—most of it bad, unfortunately.

Would you believe, looking at it, that the Royal B.C. Museum is at risk of collapsing in a major earthquake? —Wikipedia photo

You’ve needed a program to follow recent developments, all of which have been reported in the news media and in Chronicles editorials so don’t bear repeating today.

Instead, I’m gong to turn back the clock to the very beginning of our senior museum and archives, to the man who did so much to found the former by donating his personal collection of stuffed and mounted animals.

I’m referring to Jack Fannin who, if he isn’t spinning in his grave at these fumbles by RBC management and provincial government, he must be shaking his head in wonder and despair...

* * * * *

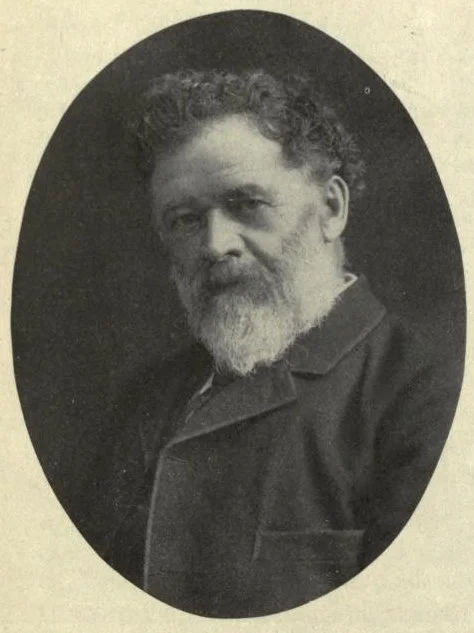

John “Jack” Fannin was a remarkable public servant. Few who knew the stocky, white-bearded figure with a braying laugh and twinkling eye realized he’d once survived one of the most terrifying ordeals recorded in British Columbia history…

“Father” of what has become the Royal B.C. Museum, Jack Fannin. —Wikipedia

“He was fond of the woods, and the mountains, liked to fish, hunt and all that kind of thing,” said one who knew him well. It’s a simple epitaph for a complex man who excelled as a natural historian, adventurer, explorer, surveyor, shoemaker, miner, musician, author, poet, prophet, composer—and great Canadian.

Little is known of Fannin's early years beyond the fact that he was born July 27, 1837, in the Ontario hamlet of Kemptville. It’s apparent, however, that young Jack grew up in the dense woods surrounding his little community. As he grew older, every tree, stream and blade of grass became a source of constant wonder and study.

Plant, animal, insect and mineral: Jack watched and marvelled at all of Mother Nature’s mysteries.

Another known fact in later years was that Jack's passion for the outdoors caused his schoolwork to suffer, for he was compelled to begin again much later in life. He taught himself all that he’d missed in class and considerably more; and he even obtained a position as a school teacher

In 1862, when the strapping young woodsman was 25, he heard wondrous tales of a gold strike in the Cariboo district of faroff British Columbia. When hundreds of people, including many of his neighbours, threw down plows and axes to follow the rainbow, Jack decided to join them.

Thus he became a veteran of the fabled “Overlanders,” qualifying for this select company by doing just that—hiking overland from Winnipeg to British Columbia

After six months of unspeakable hardship, Fannin’s party stumbled into Fort Kamloops. In Red River carts, on horseback, afoot, and on flimsy rafts, they’d battled 1,000 miles of prairie, swamp, mountain and murderous river rapids.

For the next 12 years he laboured with pick, pan and sluice box throughout much of the province without success. Disheartened at last, he turned to the less exciting but more rewarding trade of shoemaker at New Westminster until, because of his experience as a prospector, he obtained a job with the provincial government and became head of the surveys department.

His first major assignment as surveyor was no less than “Ascertaining the character and area of unoccupied lands in the valley of the Lower Fraser [River]. “With characteristic vigour, he undertook the huge task. The enthusiastic report he sent back came to the attention of Victoria's daily paper, the Colonist. As the paper commented, the report is “so highly readable that we are induced to place considerable portions of it before our readers.

“It is so much out of the dry and trodden track of official reports that we must congratulate its author upon the success with which useful information is conveyed in a popular form”.

Jack's prowess with pen, and his power of prophecy, are vividly illustrated in the following excerpt in which he describes a panoramic view of the Lower Fraser:

“Every settlement along the river can be readily seen through its windings 80 miles to the gulf, and looks still and motionless in the distance. New Westminster can be seen with the naked eye, and every settlement along the river can be readily distinguished. Sumas and Chilliwack. The former 17, the latter 12 miles away, appear almost at our feet.

“Here also can be seen in the country between Chilliwack and Cheam new openings made by recent settlers, looking upon which as new signs of awakening prosperity the imagination wanders into the future, when this green plain shall be dotted with herds and the tangled growth of forests which now covers the virgin soil of the uplands shall yield to the hand of hardy industry and fields of waving corn shall take its place.

“When the eye from this spot will rest on many a hamlet and the sound of human voices and human industry will fill the space where now is silence and solitude.

“Fanciful as this picture may seem, and I have no doubt those whose experiences have never led them beyond the beaten lines of travel through this district may think it very fanciful indeed, yet it is not only possible for this state of things to come about, but the time is not so dimly marked in the future when this very picture will become a living reality.

Time has shown Fannin’s prophecy of development in what was then unsettled Fraser Valley to have been accurate. —www.pinterest.com

“For it can scarcely be consistent with the natural course of events that this beautiful valley will remain long, as it is, a comparative wilderness while so many of our fellow beings are struggling for a miserable existence in crowded homes of the Old World.”

When next the Colonist had occasion to praise Jack Fannin, it was with blood-chilling headlines: “Amid the frosts of Stickeen! Horrible sufferings of the government explorers! Cold, hunger and grim death on every side!”

The story behind these headlines is one of incredible hardship and raw courage—typical Jack Fannin.

In October 1874, the government dispatched him to explore the headwaters of Stikine River for signs of gold. Four months later, he and French Canadian George Florrence were taken, near death, into Wrangell by an Indigenous man who’d found them.

Their story, as told by Jack's diary, is one of sheer terror.

Twice the surveyors attempted to beat upriver with supplies. The first time, their Native boatmen turned back after encountering thick ice. The second canoe attempt was defeated by the same obstacle. Retreating to Wrangell, Jack decided to await a complete freezing and try again on foot.

On December 5, “having positive information that the ice had formed, and that travelling between the mouth of the river and the Boundary Post was safe, and hoping to get over that part of the journey before the heavy fall of snow,” Jack and Florrence started out.

They estimated the 60-mile trek would take them four days and, to be safe, they packed eight days’ grub. Their journey was to last three weeks!

Soon after leaving the mouth of the Stikine, the explorers encountered the worst storm of Jack's life. For 15 days it continued with scarcely an hour’s intermission: snow, rain, and hail, accompanied by a wind so penetrating that there were moments it was utterly impossible to face it. During all this time they travelled with heads bent forward, one following in the tracks of the other, their snowshoes sinking a foot at every step.

On the twelfth day their grub gave out but there was a lull in the storm. The fog and mist which accompanied it lifted above the mountain peaks and showed them their whereabouts. They were still a few miles below the “Ice Mountain,” scarcely halfway and their provisions gone!

The men faced each other in mute horror.

When finally he was able to speak, Florrence suggested retreat. They looked back over the glittering waste of snow which had taken them 12 days to walk through, and Fannin, shaking his head, refused to attempt it. Rather, he proposed they abandon everything—including sleds and blankets—and push on to the post.

Keeping only an axe, they began the mad race against almost certain death. That night they spent ceaselessly marching about their campfire to keep warm. With morning, they pressed onward once more to encounter new-and grimmer-obstacles.

Broken ice meant wading through frigid water or constructing crude pole bridges and the shivering adventures became weaker with every step.

Somehow they pushed on, “weak and exhausted, making little headway till the morning of the third day since leaving their blankets, when shortly after starting they came to a point where further travel was blocked.”

The river was open from bank to bank with high and perpendicular bluffs on either side. Their position was grim. They could go no farther. Florrence, taking Fannin by the arm and pointing down the river, said, "We will go back to our blankets and have a good sleep.” Faith and perishing from hunger, they commenced retracing their steps.

By nightfall, Florrence could hardly stand. His desire to lie down in the snow and sleep was overpowering.

All through that haunted night, Jack talked to his comrade—talked and talked and talked until his tongue was swollen and stiff—saying anything to keep Florrence awake. At one point during this nightmare, Florrence collapsed in their campfire but was hauled to safety without harm.

The next day, while they were travelling by an open slough, Florrence stopped suddenly. Taking off his snowshoes, he plunged into the water, returning almost immediately with a salmon grasped so tightly that his fingers met through the quivering flesh.

This tiny windfall lasted five days, Fannin rationing every scrap-fins, gills, bones and all.

Finally reaching their abandoned sleds, they took one blanket apiece and staggered blindly downriver. On Christmas day they were within five miles of Wrangell but were stopped by open water. With precious axe and benumbed fingers, they constructed a flimsy raft, finishing at dusk.

Unable to wait for dawn, they set off in the darkness and had gone about a mile when they struck a rock and Jack was pitched into the river. Somehow he was able to scramble back aboard.

Now they had to land and build a fire so that he could dry out. The next day they set to work building a sturdier raft, again finishing at dusk. They were just about to shove off when a Native in a canoe chanced along. The awed saviour rushed his grotesque wards to Wrangell where Florrence “became delirious and had to be taken in charge by his friends”.

Thus ended five bitter days “without eating anything and five nights without blankets in the middle of an almost Arctic winter.” A week later, recuperated, Jack Fannin and a fresh party “started back fully equipped to have it out with the elements”.

* * * * *

In 1877, Jack had retired once again to the less rigorous trade of custom shoemaker at Hastings on Burrard Inlet (now Vancouver). Between shoe making assignments, he indulged in his lifelong passion for natural history by adding the art of taxidermy to an already impressive list of accomplishments.

The bearded bachelor in the little shop, crowded with bird, fish and mammal specimens, became a favourite of neighbourhood children who haunted his cluttered quarters in hopes of having him sing, entertain with his organ or cornet, or tell a fascinating tale of woodlore. On other occasions he led crab-spearing excursions and nature hikes about the area.

Also during this period he became internationally known as a big game hunter and guide. Then, in August of 1886, he eagerly accepted the post of curator of the newly-founded provincial museum in Victoria. To start the museum off properly, he donated his entire collection of prized specimens.

October 25, 1887, was a special occasion in his busy career.

That day marked the official opening of the new museum in a little 15 by 20-foot room adjoining the provincial secretary's office in the main building of the famous “birdcages,” the nickname given to British Columbia's original wooden Legislative buildings. Here Jack collected, assorted and preserved the flora and fauna of the province.

“So limited was the space here.” wrote a colleague, “that when the black wolf, which is still a treasured specimen of the museum, was brought to Mr. Fannin he had to take it home to his own house and mount it in an empty room, where I can remember going to see it in the course of preparation.”

Within three years he’d outgrown his cluttered office several times over.

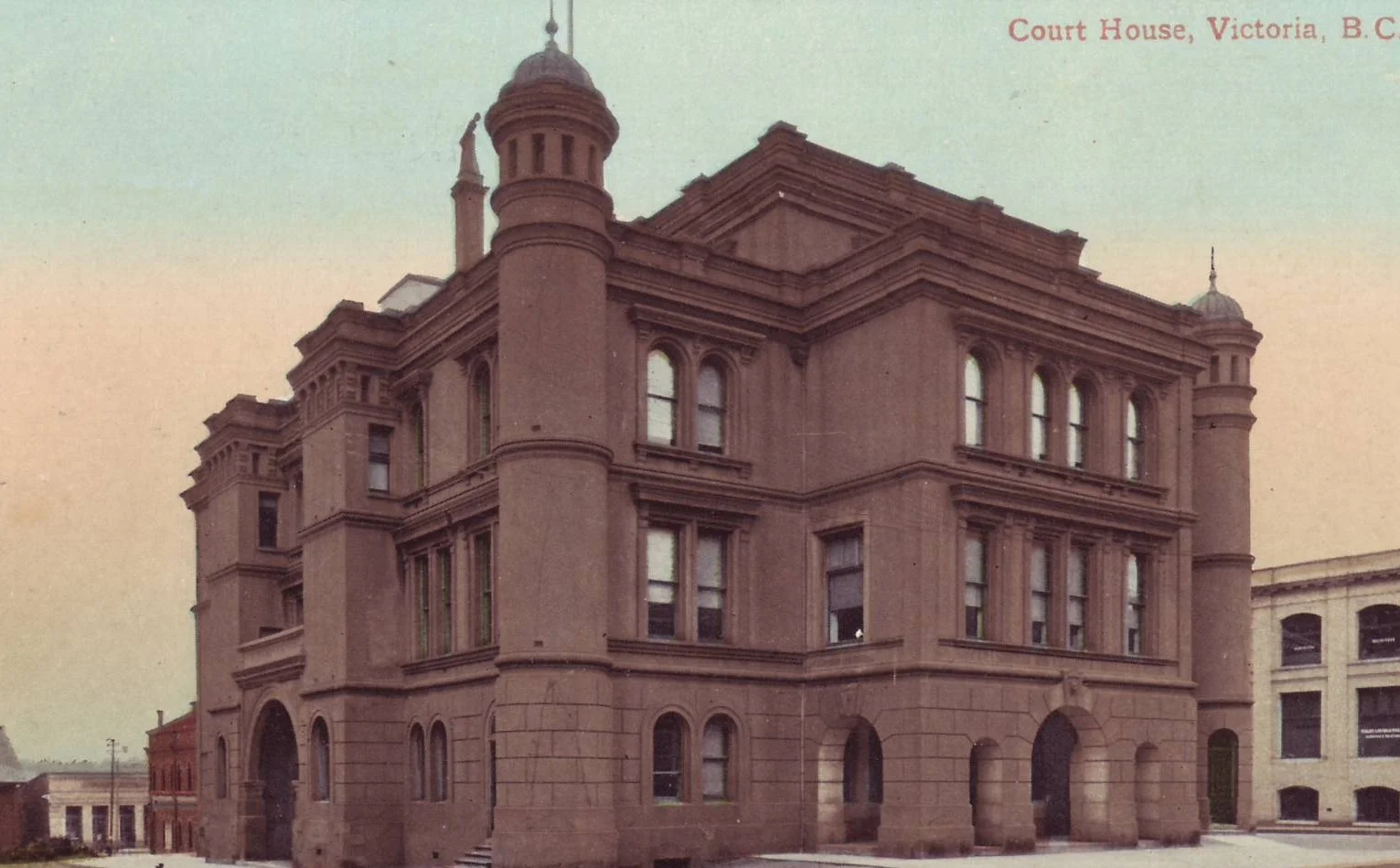

When the new courthouse was completed in Bastion Square, the delighted curator moved, lock, stock and specimen into the vacated James Bay courthouse. During this time he helped several prominent citizens form the Natural History Society to “assist in collecting and preserving natural objects for the provincial museum”.

I can clearly remember two exhibits: in a glass case, a giant replica of an earwig, so big that it gave me nightmares, and, on the wall, a large slab of coal from a mine that clearly showed three dinosaur footprints.

That one wasn’t scary but intriguing!

On opening day, May 24, 1898, H.D. Helmcken, MPP, presented the proud curator with a beautiful pipe in appreciation of his immense work. Several years before, the government had sent him on a tour of America and European museums.

But Jack Fannin was reaching the end of the trail.

After so many years of dedicated work, so many adventures, so much activity, he was stricken with illness and for his last years was a semi-invalid. Yet he didn’t retire until Feb. 23, 1904. Jack Fannin, grand old man of British Columbia's vast outdoors died four months later, aged only 66.

“In the death of John Fannin, late curator of the provincial museum,” said the Victoria Daily Times, “British Columbia lost not only one of the best known of her pioneers but one whose life's work will go down to posterity as among the most useful and conspicuous in the history of this century.

“A love of hunting, adventure, the insatiable craving of the man to study nature's laws, particularly as seen in animal life, a rare intelligence for comprehending things, and an artistic faculty for imitating them, were but some of the chief characteristics of the deceased.

“But this is not all that makes the memory of the late Mr. Fannin so fresh in the minds of many surviving him. He has left behind monuments to his skill and energy which can never be disassociated with the history of the pioneer days of B.C.”

Many Victorians mourned the old man in white beard whom they’d seen so many times, standing like a statue near Beacon Hill Park,listening intently to robins singing, or watching them flit from branch to branch.

Beacon Hill Park. —Tourism Victoria

Others recalled his “air-cleaving” laugh which, “once heard, could be recognized from the Rocky Mountains to the Coast.”

A quarter of a century later, the Geographic Board of Canada acknowledged Jack’s enormous contribution to posterity by naming after him a lake, a creek and a group of mountains near Burrard Inlet.

In northern British Columbia an intermediate subspecies of the stone sheep was named Ovis Fannini.. But probably the development most satisfactory to Jack Fannin is the fact that the collection he started in a 300-square-foot room has grown Into a magnificent, multi-million-dollar museum that actually attracts hundreds of thousands of visitors.

Today the RBC Museum’s collection comprise approximately 7 million objects, including natural history specimens, artifacts and archival records.