John Butts, King of Knaves

Part 1

So who is Victoria's most outstanding character?

Such a distinction might seem to be a difficult one to assign, given the many weird and wonderful individuals who’ve walked our Capital’s streets during the past 160-plus years. But there is one man who stands head and shoulders above all the others.

Without doubt, the most fabulous character ever to call Victoria home port is John Butts. Or John Charles Butts, ‘town cryer to her Britannic Majesty,” as this rogue preferred to call himself. A newspaper of the day expressed the view of many citizens when it declared John to be “a greater scourge than cholera or smallpox.”

The legendary John Butts as artist Dean Lewis’ portrayed him for the cover of the author’s book, Capital Characters: A Celebration of Victorian Eccentrics. —Author’s collection

John usually held forth at the corner of Yates and Government streets. In his baggy, dirty suit and wearing a belt that was two notches too slack about his protruding belly, this Englishman from Australia would announce forthcoming events and deliver commercials for city businesses in his “magnificent" tenor voice. Upon attracting the attention of passersby with the aid of a hand bell, he often threw away the script and gave impromptu performances.

More than once, these led to audience participation when the listener, taking exception to John's repartee, ended the act with his fist, foot or walking stick! Assaults and appearances in court court were occupational hazards for this hero.

John was not only anti-establishment but anti-everything that smacked of respectability. His being incurably lazy, a drunkard, thief, beggar and bootlegger in no way dampened his enthusiasm for calling names and poking fun at the more proper members of his of the community. As can be imagined, his efforts in this direction were unappreciated by leading Victorians.

Little is known of John Butts’ background other than the fact he landed in Victoria in 1858 (one step ahead of the San Francisco vigilantes, it was rumoured) and that he could wax eloquent when occasion demanded. Some took this to be an indication of respectable birth and an education which John seems to have done his best to live down.

Not that his degradation occurred overnight. The first recorded mention of him in Victoria announced that he’d offered himself for election to the House of Assembly. His campaign was almost stillborn when the same newspaper reported, just days after, that he’d been summonsed for striking a small boy. John managed to settle this embarrassment out of court and, three months after, faced the electorate with all the confidence of a new bride.

Against such formidable opponents as Attorney General George Carey and solicitor George Wright, Butts announced himself to be ready, willing and able to attend to his constituents’ needs as their assemblyman.

The Colonist, somewhat tongue-in-cheek, wished him well: “Having an intimate knowledge of government, being no party-head, and withal, having accumulated considerable money, he is no ‘man of straw,’ and hence fully believing that this constituency has common sense enough to canvass the merits of all the candidates, he hopes to successfully oppose both the learned gentlemen now in the field”.

Perhaps it was losing this electoral joust that turned John against the establishment. It's the last time we read of him playing it straight, or of his being a man of means.

Charged five months after with “one of the most abominable crimes in the calendar," John faced his accusers in court. Although newspaper accounts gave few particulars of the case, which involved a 16-year-old boy, John escaped with his honour intact. After defending himself with eloquence, the three prosecution witnesses having contradicted each other throughout their testimony, John listened with relief as the magistrate dismissed the case.

Bastion Square Police Barracks also housed the courtroom and city jail which came to serve as John’s second home. —BC Archives

During his brief stay in Bastion Square police barracks, he seemingly came to enjoy the room service for, upon acquittal, he chose to remain several days more. This seems to be the one and only time that John expressed a liking for jail; he’d exercise every argument to avoid Her Majesty's hospitality thereafter.

Within a month of acquittal, he again faced the bench, Frederick F. Davis having charged him with assault. John, he said, had kicked him “in the pants". Butts stoutly denied it and argued that he was the victim of a conspiracy. The magistrate, however, chose to believe Davis and John was given the choice of paying a fine of three pounds or 30 days in the slammer.

To date, John’s sins against humanity (at least those proven) had been slight. However, in the spring of 1860, he committed the heinous crime of bootlegging. Police Sgt. Taylor had pinched him in the act of selling liquor “across the bridge” on the Songhees Reserve, on the west side of the Inner Harbour.

“Poor Butts," lamented a reporter in mock sympathy, “will hardly escape the chain gang this time."

The magistrate heard John's impassioned plea, a tale of woe he used for the first time, and one which he’d use in succeeding appearances in police court. He had, by “patient industry,” he sobbed, saved $4.87 towards the $5 required to book passage for Australia. Only after having exhausted every effort to raise the necessary quarter had he, in desperation, turned to crime.

But the verdict was guilty and off John went, to repair city streets.

Six pounds of iron around his right ankle did little to set him on the path to righteousness, however, and shortly after his release, he again graced the dock. Upon finding him guilty of his second count of bootlegging, Magistrate A.F. Pemberton sentenced him to “three moons” in the ball-and-chain brigade.

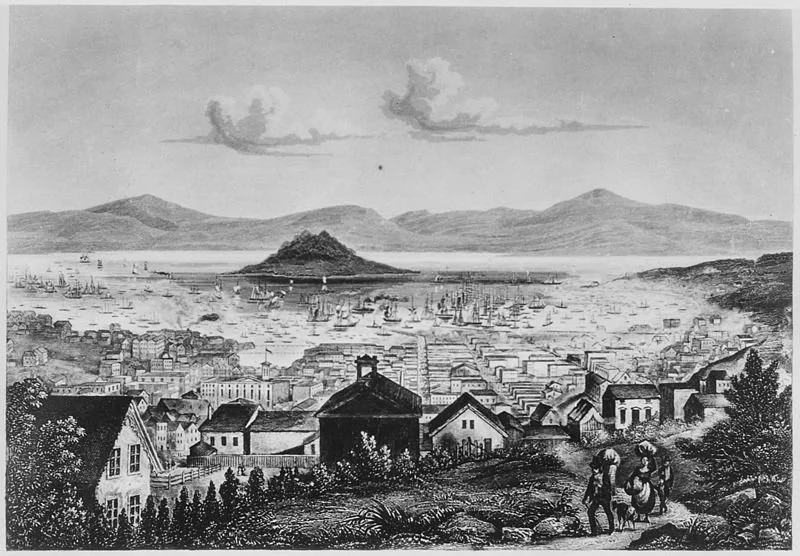

San Franciscans were warned that Victoria’s notorious town crier was headed their way. —Wikipedia

An idea of John's growing notoriety can be gained from a San Francisco newspaper warning to its readers that Victoria's infamous town crier planned to visit the Bay City. “Secure your mutton!” cried the alarmed scribe who obviously was unaware that John was yet serving his second term for bootlegging tangle-leg whisky.

No sooner was he back on the street than John was up to his old tricks. Upon taking his place in the dock, a blushing Butts listened eagerly as his arresting officer informed Magistrate Pemberton that the leading prosecution witnesses were unavailable. Such a golden opportunity wasn’t to be missed. Drawing himself erect, he asked Pemberton if he’d convict him on the mere say-so of a constable. Sobbing fitfully, he argued: “Haven't I always pleaded guilty when I was convicted [sic!]? Did I ever grumble at Your Honour’s decision?

“Never! Never! Allow me to remind Your Worship of a good old saying—one that I learned at school—that says: “While the lamp holds out to burn, the vilest sinner may return,” and do not convict me of a charge of which I am totally innocent.”

Moved by this impassioned plea, Pemberton, ever a sucker for a good sob story, replied, “Well, Butts, I don't wish to injure your good character; you may go.” Instantly, to the delight of the galleries, John was out of the dock and out of the court, a grin slashing his dirty face from ear to ear.

When next he faced Pemberton, just two weeks after, charged with vagrancy and, surprise, bootlegging, his usual eloquence failed him and he waited silently for sentencing. He asked only that he be allowed to board a ship for Australia, “his homeland,” and forever forsake the streets of Victoria.

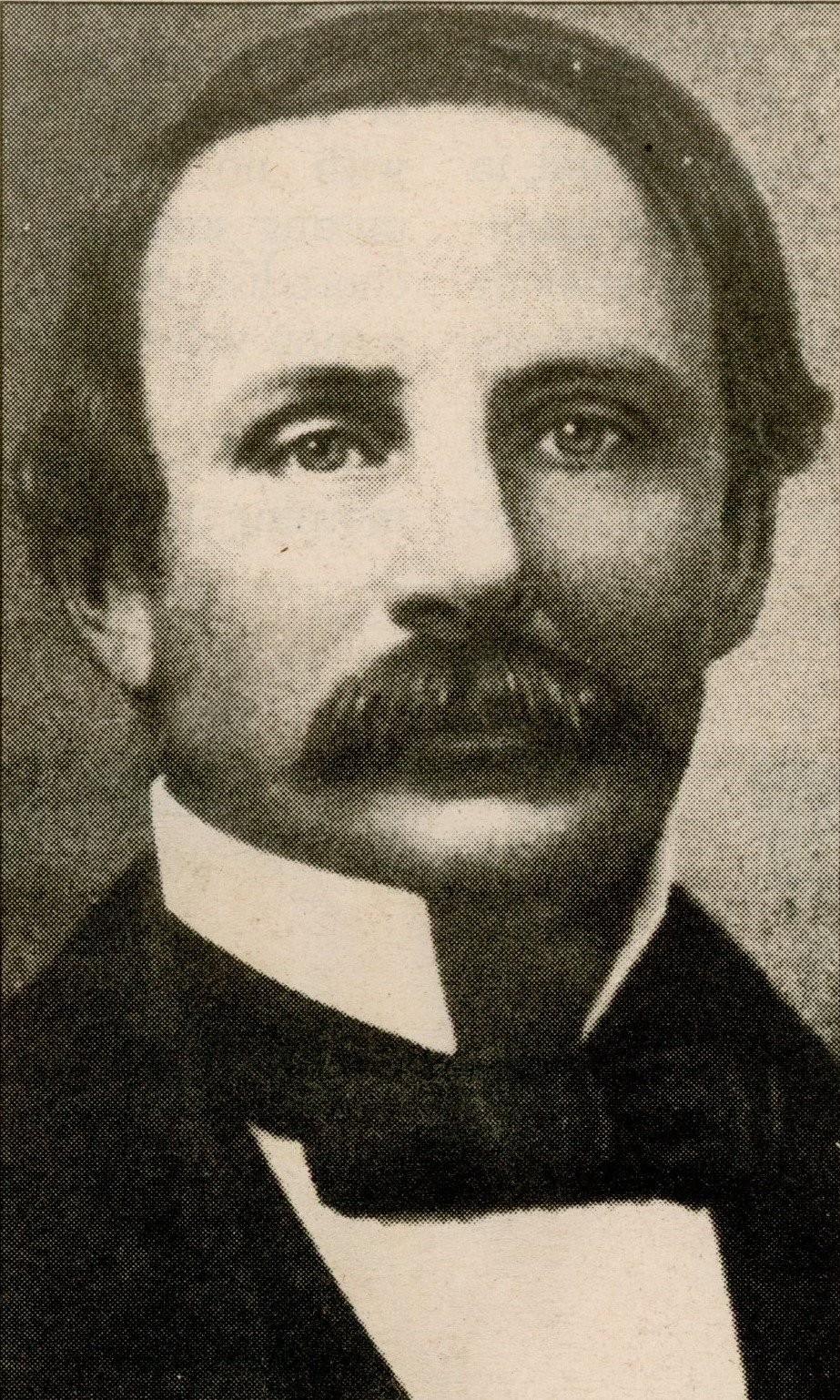

Victoria Police Magistrate Augustus F. Pemberton was a sucker for a good sob story. —BC Archives

As much to his amazement as that of spectators, Pemberton, undoubtedly overwhelmed by the thought of seeing the last of him, accepted Butts’ offer to emigrate. Before he could change his mind, John was out of the court and free, with no more intention of leaving Victoria than Pemberton.

For three full weeks nothing untoward was heard of John. When he again made news, it seemed that he’d turned over a new leaf. Not only had he become a model citizen but a missionary to boot as he delivered the word of the Lord to a devoted Indigenous following who met regularly in his college. There, in his “Congragational Church,” John would begin services with a prayer, followed by a hymn. After a “short and feeling address” and another hymn, the collection plate would be passed around and the congregation dismissed with a benediction.

Of course, it was too good to be true. A correspondent who identified himself only as “Fort Street,” informed the Colonist: “After the services, dancing, smoking and drinking whisky are the order of the evening—Butts acting as barkeeper with as much grace as he a few minutes before officiated as clergyman. It is quite an ingenious plan and the inventor is, no doubt, making a ‘good thing’ by administering spiritual comfort to his flock in two totally different ways!”

Despite this publicity, John continued to attend to his “congragation’s” spiritual needs, unmolested by police, for three weeks before he was nabbed for bootlegging and a “general inclination towards loaferism”. Once again, he faced a memorable encounter with a frowning—but oh, so gullible!—Magistrate Augustus Pemberton.

As ever, he had a ready defence, one generously spiced with Biblical quotations and classical poetry that, not for the first time, made some Victorians wonder if, deep in his past, John had had a good upbringing and formal education.

For good measure, he threw in his oft-used promise to leave Victoria for Australia aboard the first American ship if given the chance. Concerned that Pemberton might not fall for this ruse again, he went one better by offering to take under his wing a fellow prisoner and town nuisance. Poor Scotty had been arrested for faulty navigation, the result of his having taken on board too heavy a cargo of spirits, and he was faced with having to pay a stiff fine or being dry docked if convicted.

Not only would John remove himself to greener fields if released, but he’d relieve the city of Scotty—“this poor, lost wretch”—by taking him along. “I'll buy him a new suit of clothes before he leaves here, and I'll give him one pound before he gets there,” avowed the magnanimous and by this time sobbing bootlegger, “in order that he may not land a pauper. As for myself, I have only one ambition left: it is to reach my native land and die in peace at the old homestead.”

One can picture the stocky crier, his belt buckle below his beer belly, tattered hat in hand and tears streaming down his dirty cheeks as he promised to rid the city of not one but two nuisances.

All the while, the austere, mustachioed Pemberton glowered downward, inwardly torn as to whether he could believe Butts’ appeal this time. Finally, his better nature went out and yet undecided, he reminded Butts for a week. Scotty was released.

John's reprieve ended not a week but three days later when Pemberton, obviously having had second thoughts, rapped him with three months in the chain gang.

This latest indignity proved to be too much for John's frail constitution. When guards tried to rouse him one morning for work in the streets, they found that the town crier was paralyzed from the waist down. Doctors who examined him gave him little chance of recovery. Within hours, words swept the city: John Butts was dying!

(To be continued)