John King Barker

Times had indeed changed for John King Barker, back in 1906.

Although he had much in common with Billy Barker, the namesake for British Columbia’s most famous ‘ghost town,’ John King Barker had his own story to tell. —BC Archives

Gone was the fortune he’d spent a lifetime wresting from the soil; gone were his youth and his health. Old, bent and feeble, the miner hoped to visit an old friend one last time before joining those of his comrades who’d passed on before him.

But if the road that stretched before Barker, 118 years ago, was short and narrow, that behind him was as as long and colourful as that of three normal human lifetimes: a career as a prospector and adventurer which makes a modern reader marvel at the hardships that pioneers contended with in their search for gold.

* * * * *

Alas for the historian, Barker, in recounting his career to H.J. Lipsett of Olympia, Wash., found it necessary to greatly condense his story, with the result that much of interest and of historical significance is left to conjecture. The portrait which remains is that of an ‘ordinary’ man who, like thousands of others, came to British Columbia in search of fortune and helped, in the process, to build a nation.

In two short sentences, Barker (not incidentally, William Barker, founder of Barkerville) spanned the period between birth and adulthood, noting only that he was born in Hampden County, Mass., on Sept. 26, 1825, and that, upon growing up, he turned to work as an itinerant blacksmith. By the spring of 1850 he was restless. In far-off California, gold had been found the previous year and the resulting stampede had turned the attention of all America and much of the world upon the unknown western frontier.

Among those who succumbed to the gold bug was John King Barker, 25-year-old blacksmith. Proceeding to New York by the Hartford and New Haven Railway, he boarded the Panama-bound steamship Ohio. His ticket, Parker recalled, for passage to Havana, cost $60—a small fortune to a working man.

Once in the Cuban City, he planned to embark upon the steamship Falcon for the remainder of the voyage to Panama, only to learn upon arrival that the Falcon could take only a third of the hopeful passengers waiting there. Barker had no choice but to re-board the Ohio and continue on to New Orleans where he embarked upon a Gulf steamer for Galveston, Texas.

This unforeseen change of schedule almost proved disastrous when, deep in the Gulf of Mexico, his ship threatened to sink under him during a storm. However, she pulled through and, not one to be discouraged by misadventure, Barker remained aboard her for the passage to San Antone, arriving in that port in May. There, a large party of argonauts was forming for the trek cross-country to the gold fields. Restricted to men, the expedition included 800 mules and horses. At San Pedro Springs, it took the small army three weeks to organize.

On the historic morning of June 1, 1850 (Barker seems to have had a photographic memory when it came to date), the gold seekers, under command of Parker H. French, headed west for fame and fortune.

John King Barker was one of the many who left home to seek their fortunes during the California gold rush. —Wikipedia Commons

It was then that the “fun” of breaking in the green mules began; as well as the fun which resulted when many of the expedition left before their credit could be checked.

Before long, Apaches had cut loose 28 mules from the train, one man being killed in the resulting stampede. By the time they reached El Paso, most of the expedition was disheartened and voted to designate certain elected officers to sell their outfits to the Mexicans. Barker received 75 Mexican dollars for his when, with John Valentine, a fellow native of North Hampton County, he joined a Mexican mule train bound for Albuquerque, N.M.

But the Massachusetts adventurers decided, at Durango, to join a party of 50-odd Americans when, without giving details, he mentions having witnessed his “first full fight”. After only four days, there was a further re-shuffling of men, Parker and Valentine then organizing their own party of 14 for the trek over the mountains to Mazatlan. After purchasing fresh mules for $10 each, they headed westward and, in due course, arrived safely at that port where they waited a week for a steamer to call.

When the Charleston docked to load cargo for San Blas and San Francisco, they paid their fares of $33 a man and board. The inference between the lines of Barker's reminisces, as recounted more than half a century afterwards, seems to have been that $33 was a high price to pay to sail on a ship loaded with “turkeys, chickens, hogs, sheep, cocoa oil, etc, and...took a long time to get all the goods on board".

Whatever—finally—they reached the Bay City, gateway to El Dorado, on February 22, 1851—10 long and hectic months since Barker bade farewell to Hampden.

The Charleston anchored off the intersection of Leedsdorf and Commercial streets, there being no wharf facilities at that time—“only a few poles driven in the sand and a plank run out on them to get ashore on. The water at that time washed back as far as Montgomery Street."

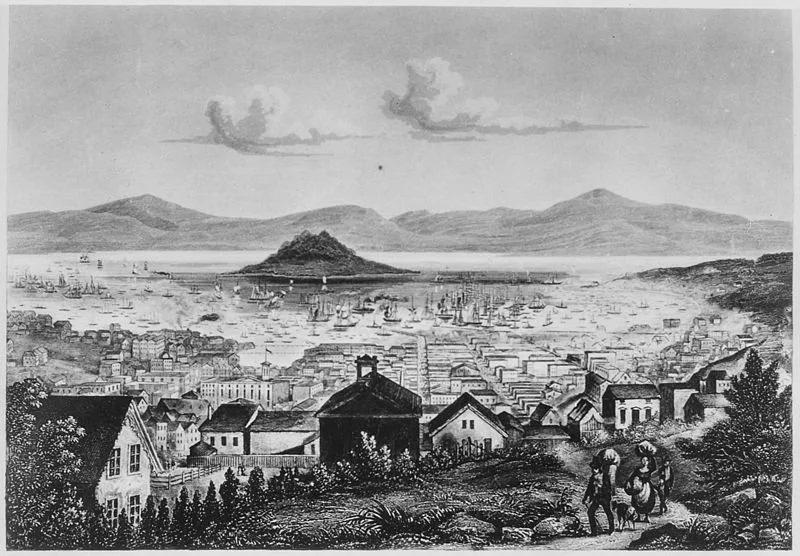

San Francisco in the 1850s as it would have looked at the time of King’s passing through on his way to the interior gold fields. —Wikipedia

As the San Francisco of 1851 also lacked most amenities, Barker spent his first night in town aboard the old whaler Niantic, then used as a floating hotel. With four ancient sisters, the Niantic was beached at the foot of what was to become Sansome Street.

After five days in the Bay City Barker boarded the steamer Seabird, Capt. Tichner commanding, for Humboldt. By this time, only nine of his party remained. As it turned out, their arrival at Humboldt was something of an occasion as the Seabird delivered the town's first shipment of U.S. mail. Townspeople marked the event by staging a celebration and firing off an old cannon; a festivity dampened when the old field piece exploded, killing one of the celebrants.

For his own for his part, Barker found five days in Humboldt sufficient. The fact that he’d been forced to spend his nights “camped in a redwood hollow tree” likely detracted from the region’s scenic wonders and, upon learning that a Capt. Smith of Arkansas operated a pack train to the mines, the adventurers agreed to join him.

Barker had to trade his Colt revolver for a mule. —Wikipedia

However, with limited cash reserves and freight costing $1 a pound, Barker found it necessary to trade his Colt revolver for a mule. In worldly goods, he was somewhat better off, being unable to pack all of his outfit aboard the mule. So, with several others, he cached his surplus gear in the hollow tree; although they all planned to retrieve the equipment later they never saw their possessions again.

Heavy rains slowed the trek to the mines to a crawl. "We were two days to Mud River, three days more over the mountains to Big Bar. "But his own misery during these five days was alleviated somewhat by the presence of the first white woman to make her way to the Big Bar goldfields.

"I was so fat that I got tired and fell asleep on the trail. I awoke in the evening and made my way to the camp where this good lady made me a bowl of venison soup which was really good. She and her husband stayed at Big Bar, she making Sunday dinners for the miners and washing clothes, etc. They made a fortune and afterwards went east to Wisconsin.... "

But if the enterprising couple made their fortunes and went east, Barker and company did just the reverse. In short, they went broke.

Before long, the entire company was reduced to $5 and ‘Doc’ Jan Fleming of Nashville who proved to be a medical marvel when he cured a patient and restored the group’s credit rating. Upon being called to the ailing and filthy miner’s side, Doc Fleming refused to attend to the man’s affliction until he was bathed. That accomplished, he took four pills from a tin case, gave the patient two in capsule form, then crushed the others into a powder. Just what the miracle-laden pills contained, Barker didn’t know. But when the patient recovered, their grocery bills were temporarily taken care of.

Then the party split once more, Barker and two others striking out for Weaverville. For a mule, the penniless prospectors traded some traps to several newly-arrived carpenters from Sacramento. Several miles along the trail, which climbed high bluffs above the river, their newly traded mule rolled over the edge and all the way down to the water.

Amazingly, it escaped uninjured and with the help of miners who’d witnessed the incident, they soon had the animal back on the trail where, exasperated, Barker sold it to its rescuers and proceeded to Weaverville on foot.

“...We arrived that evening and got supper in a log house. With no flour the price of the mail was $1. We found 5,000 people at Weaverville; mostly in tents. There were two log houses and one conical tent, used as a gambling tent."

There, Barker met a miner bound for upper Trinity River. Setting out together, they paused at a small settlement to earn a grubstake. Some weeks after, miners from up-country sent word that they’d pay “fresh gold” for a cradle. Sure that this meant they’d made a new strike, all workers downed tools and elected a party of six, including Barker, to find out. When these scouts reported that the miners had in fact found gold, 15 were delegated to stake claims for the rest.

Their arrival at the new diggings, deep within hostile Indian territory, prompted the original claimants to abandon their claims on the condition that they weren't followed. This happy development meant a change in fortune for Barker and friends, and the men set to work “with good results”. When the strike began to peter out, they moved on to French Gulch, then to Shasta City, where Barker, Jack Fanning, the Porter brothers and the Timming brothers “bought an old mine from a man and his wife, and we made money out of it".

After two or three months of this, Barker moved on to Sacramento.

“From Sacramento I went to Auburn and American River, where I mined for about three years. I was one of the first at Michigan Bluff... I was one of those who first brought water to Michigan Bluff ditch. There were about 21 miners about this part and we took up all the land we could get and divided it into 21 claims. Then we put 21 cards in in a hat and drew. The card drawn was the number of the claim you got."

Although he didn't say, Michigan Bluff must have been another profitable venture as, at his most next operation, at Antwine Canyon, he bought his “ground at $1 a foot and made money". That winter, he rested in style before proceeding to new diggings in the spring.

As before, he did well; at least until he reached the present site of Bloomfield, where quicksand buried his laboriously dug mine shaft. Then he worked his way from camp to camp until the fall of 1862. Back in San Francisco, having resolved to try his luck in Australia, he encountered four old friends who were wintering there from Cariboo.

“They gave me so good accounts of Cariboo that I went back there with them."

Thus, in the spring of 1863, John King Barker, 13-year veteran of the California goldfields, stepped ashore in Victoria from the steamship Active. After two days in the Anglo-American Hotel, his party sailed for New Westminster aboard the steamer Enterprise. At Harrison River “we transferred to Bill Moore's scow—an open boat with no covering on her deck. Her engine was an upright engine on the stern..."

After staying overnight at Port Douglas, they proceeded on foot with their supplies on their backs. There followed a stop-over at “Joe Smith's father's," passage by whaleboat and steamer to Pemberton, then a hard day's trip over the portage to Anderson Lake, another boat ride and another four-mile portage to Seaton Lake. Finally, a third steamer to Cayuse Creek where they “walked seven miles over a good road to Lillooet.

They re-crossed the Fraser River by ferry at a spot called Lorenzo where, much to Barker’s surprise, grapes were being grown. Then it was on to Marble Canyon over the Pavilion Mountains and down to “Kelly's Lake” and a roadhouse run by an American “hunter.”

Their journey wasn’t done. "The next day we got to Clinton, 47 miles from Lillooet. Next day, we went over a tall mountain called Green Timber [and] stopped with George Walters at 82 Mile House; next to the 105, 108 and then to the 111, where the road ended. Then on to the 117, run by McKinley, who cut the first tree to build Fort Walla Walla and who was there when Marcus Whitman was murdered.”

The road stops (to the reader) were reached with almost monotonous regularity: 120 Mile House, 121 127 (also known as the Blue Tent). "The road was here known as the Brigade Trail that went to the Peace River; then to the 141 kept by Murphy; then to the 144 kept by Fuller; then to the 150 kept by the Davidson Brothers."

‘Clean-up’ on the rich Cariboo Hydraulic claim in 1897; by then, Barker and partners had sold out “to some CPR officials”. —BC Archives

And so it went, mile after wearying mile, roadhouse after roadhouse: Soda Creek, Mud Lake, Australian Frank’s, Elsmore's, the mouth of the ‘Quesnelle’, Lightning Creek, Beaver Pass, Jack of Clubs Creek, and—finally—Richfield, where, for the first time since leaving New Westminster, they cooked their food “and slept in blankets".

They hadn’t stopped at a single tavern along the way as meals cost an exorbitant $2.50.

“Richfield was in the heart of the mining district. There were four cabins, courthouse, gambling houses. Every man was a Californian. Meals were $2.50 each. At Richfield, I got my first work from J. Ricthie, staking the Cariboo claim. I went on a mile to Barkerville, where I boarded at $33 a week only. Then I bought groceries for $85 and carried them home in a red handkerchief to my sleeping place under a log(!)

“I had about $2,000. I sank a shaft near here and got broke and had to go to work for Johnson Peoples as a blacksmith."

Discouraged by the high cost of living, and poor returns, Barker returned to California to make $700 in a claim at Soda Bar—then promptly returned to Barkerville. With two new partners, Jack Edwards and George Devoe, he found “good prospects” near the mouth of the Quesnel River. The Aurora claims kept Barker and partners occupied for four years, when money again ran out.

For the next 11 years he served as road boss from Snowshoe Creek to 150 Mile House.

In 1889, he “located a claim on the Quesnel River, halfway between the lake and the mouth. I organized the company known as the Caribou Hydraulic Company, capitalized at $150,000. We put in some ditches and in 1893 we sold out to some CPR officials, and I went to the Peace River country, but I do not remember much after that time.. “

The Cariboo Hydraulic Mine in 1896, three years after Barker and partners sold out. Imagine having to hand-pick your way through these blasted boulders. —BC Archives

At the time of his interview with H.J. Lipsett, Barker was 80-years-old, tired and bent. His wonderful memory was beginning to fail him (at least as far as more recent events were concerned), and he was en route to California to visit an old friend.

That done, he said, he'd be on his way once more—back to B.C. and the miner’s life he’d loved for more than half a lifetime and half a century.