Jolly Jemmy Jones, Our Most Outrageous Mariner

Part 1

He was a public nuisance, a drunkard and a scamp; some even said he was crazy. Others went so far as to brand him a pirate.

But when he’d finished he’d, single-handed. defied and defeated the courts of three nations. When he died hundreds, from British Columbia to South America, mourned the wild, exciting and outrageous Welshman known as Capt. ‘Jemmy’ Jones...

* * * * *

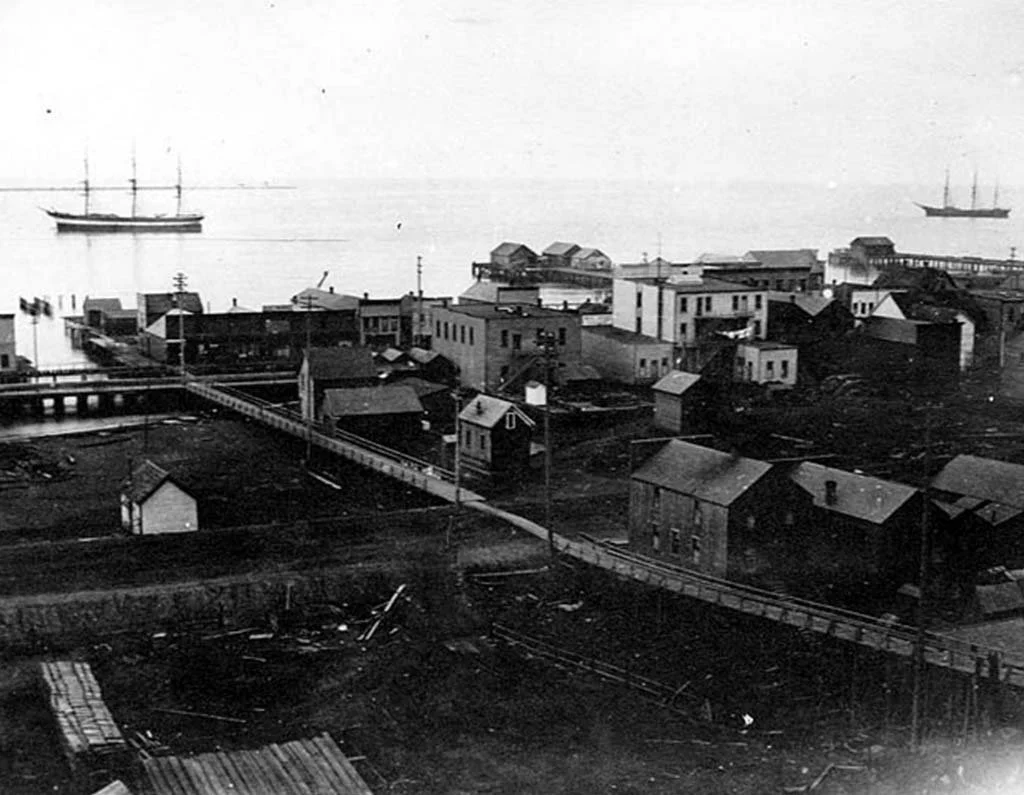

Victoria Harbour, home port to the enterprising and always entertaining mariner, Capt. Jemmy Jones. —Author’s Collection

I’ve written about scores of memorable characters over the years, even a book, Capital Characters: A Celebration of Victorian Characters—about the good, the bad and the ugly, as they say in the movies. But there was none other like Jemmy Jones whose exploits made newspaper headlines for years.

Maddening as he was to the legal authorities of the day, he made his mark with daring, invariably with humour. If there is a Heaven above, he’s up there now, still chuckling at how he repeatedly defied authority, outwitted the officers of the law who’d vowed to get him, and became a living legend in the process.

* * * * *

Marine charts show the nondescript islet at the entrance to Cadboro Bay as Jemmy Jones Island. It’s a modest enough monument to Victoria’s very own “pirate.”

Known throughout Puget Sound and B.C. waters as “Jemmy” to his admirers, the “irrepressible” Welshman began his memorable career as a teenager by searching for a wandering father. A quest that saw him working in the coal mines of Pennsylvania before travelling overland to Utah with the Mormons.

A statue depicting the epic trek of the Mormons across America. No Mormon himself, Jemmy probably believed in the safety of numbers.

In 1840 he made his way over the Sierras to join the mad rush of gold seekers to California. Almost five years of prospecting without striking it rich prompted him to move on, this time to a fledgling coal mine at Bellingham Bay. There, for the first time, he made enough money to buy the schooner Emily Parker, just in time to share in the trading boom sparked by the Fraser River gold rush.

He operated the schooner between Vancouver Island and Puget Sound ports for five years until she burned to the waterline off Victoria’s Clover Point.

Trading seems to have been profitable as he built a new schooner, the 30-ton Wild Pigeon. Her career was even shorter than that of the Emily Parker; while attempting to clear Victoria Harbour in a squall on New Year’s Day, 1858, the Pigeon capsized. Capt. Jones and his five passengers, including three women, were rescued. One, a Mrs. Ross, suffered burns and bruises from having the hot stove topple on her.

Jemmy, undaunted by this latest setback, commissioned Port Townsend shipwright Franklin Sherman to build a third schooner, to be called Carolena.

His luck held true to form.

Less than three months later, the master of the schooner Leonede arrived in Victoria with word that he’d encountered a schooner on its beam ends. It was the Carolena.

Although known to be a heavy drinker, and despite his record of three three shipwrecks in short order, few seem to have doubted Jemmy’s seamanship. In fact, he apparently made a record 28-hour run under sail between Nanaimo and Victoria, carrying coal. Forty years later, this record still held.

In May 1859, the fleet Carolena made an impressive trip from Victoria to Port Townsend, Steilacoom, Nisqually and Tumwater, Olympia and back in four days.

It was during one of his runs to Puget Sound that Capt. Jones first made newspaper headlines—as a hero.

While sailing from Victoria to Port Townsend, he encountered an Indigenous war party, 90 strong, in their canoes. They were on their way, they obligingly informed Jones, to murder an American lighthouse keeper as retaliation for some of their own having been arrested by a U.S. Revenue cutter.

Jemmy immediately made sail for the lighthouse and evacuated the keeper and his wife, leaving a man to guard and operate the light while he scurried back to Port Townsend for help. With a volunteer army of 14 (as many as the Carolena could carry), he returned to the lighthouse.

The war party had already landed and were determined to have their revenge so Jemmy disembarked the volunteers on the opposite side of the island and saved the day.

But his seamanship remained spotty.

Caught in a gale off the entrance to Esquimalt Harbour, the Carolena was driven ashore, forcing Jones and five crewmen to swim for their lives through a boiling surf.

All made it to safety and, with the help of seamen from the naval base, he soon had the Carolena re-floated and repaired. Only two months later, he was again aground, this time off Nanaimo, but without damage to his ill-starred schooner.

His misadventures at the helm of the Carolena continued, Cadboro Bay’s Jemmy Jones island and misspelled “Carolina” Reef denoting yet another of his hiccups at the helm. Some historians have rudely suggested that, perhaps, Jones’s fondness for distilled drink was the cause of his frequent accidents. More likely, it was his willingness to set sail in all kinds of weather and in waters barely charted.

Whatever the cause, Jemmy decided to swallow the anchor and sold his beloved Carolena for $1500. In the service of the famous Metlakatla missionary William Duncan, she sailed northern B.C. waters for years with, we must suspect, fewer mishaps.

In his own way missionary William Duncan was as much a rebel as Jemmy Jones. —www.biographi.ca

But Jones couldn’t forsake the sea and, despite his reputation for sinking his commands, he persuaded Port Townsend shipwright Sherman to underwrite half the costs of building a new schooner. Before long, in command of the new Jenny Jones, he was again trading between Vancouver Island and Puget Sound ports.

Characteristically, he hadn’t returned to sea without controversy—the “Welsh maid” had almost created an international incident while still on her builder’s ways.

At this time, the American Civil War was in its final stages. Around the world, Confederate commerce raiders had destroyed millions of dollars worth of Union shipping. When it became known that Jemmy Jones was rigging a new ship, U.S. naval authorities became convinced that such a rogue as Jemmy must be intending her as a privateer and dispatched the USS Naragansett from San Francisco to investigate.

Because Confederate commerce raiders were a real threat to Yankee shipping around the world, American authorities became alarmed when they learned that the roguish Jemmy Jones was building a new ship.—American Battlefield Trust

The British Colonist defended Jemmy with a chuckle: “Certainly neither Jemmy nor Jenny have a piratical look,”

Events would soon change the editor’s mind on this point!

Back in business as a seagoing trader, Jones soon had the clipper-rigged Jenny converted to steam and, later the same year, bought out his partner. His only bump during this period seems have been a minor run-in with American customs officers who charged him with an unlawfully stowed cargo of ale and porter.

His relations with American officials must have remained cordial as he was chartered to take Washington Territory Governor Pickering and entourage on a tour of Cape Flattery First Nations settlements.

Previously, a Colonist reporter had visited the new Jenny Jones at her Victoria dock where he “found the active little Jemmy in attendance on his countrywoman with all his native gallantry. Nothing, in fact, has been spared to tender her the most perfect of her kind. Dropping the figurative, the Jenny Jones has really been turned [referring to her conversion to steam] into a most serviceable boat.

“Her machinery by those excellent machinists Messrs. Spratt and Kriemler of the Albion Works is the ne plus ultra of neatness and compactness... A house has been fitted on deck and sleeping accommodations can be provided for 28 passengers aft and several forward... She will carry about 50 cattle and 100 tons of freight.”

However, if Jemmy’s ability to survive the elements had improved, his navigation of financial shoals hadn’t.

For some time he’d been evading his creditors. This erupted early in February 1865 when ship chandler McQuade and “those excellent machinists” Spratt and Kriemler had sheriffs register Jemmy in the home for insolvents—debtor’s prison.

Albion Iron Works owner Capt. Joseph Spratt lost patience with Jemmy. —Wikipedia

Newspaper headlines informed the world of Jemmy’s fall from grace and the immediate consequences. What the Colonist described as “remarkable for the reckless daring with which it was carried out,” the editor of the Chronicle termed, “a daring outrage.”

Early the previous evening, 30-40 men, some of them armed with pistols and knives, had boarded the Jenny Jones, then moored alongside the Hudson’s Bay Co. Warehouse. On board were two sheriff’s officers and their assistants. When one of them tried to resist, a member of the boarding party thrust a revolver into his face and threatened to “blow his d---- brains out.”

The sheriff’s men were locked in the forecastle, the hatches battened down and the ship’s lines cast off. The reason for the number of invaders became apparent when they attached the Jenny’s line to rowboats which towed her out of the harbour. Once at sea, the sheriff’s men were set off in an open boat and the Jenny Jones sailed for the American side, relying on sail as some of her machinery had been dismantled and impounded in Victoria’s police barracks.

This, the “pirates” only learned upon raising steam; nevertheless, they made a clean getaway to Port Angeles, the Chronicle raging: “The act is clearly one of piracy, or at least barratry.

We have had altogether too many outrages of this kind practised here, and it is high time that the strong arm of the law was stretched forth and the offenders brought to justice.”

Apparently the identities of many of those involved were known; while most had stayed with the ship, many had returned to town and “are walking the streets with undisturbed impunity”.

The Jenny’s freedom was brief, however as her temporary master could produce neither register nor manifest, she was seized by U.S. Customs.

From his cell, Jemmy assured a Colonist reporter that he’d had nothing to do with the plot to free his ship, that his last orders to his crew were to obey the sheriff. This appears to have been the case as it was rumoured that the Jenny had not been spirited away by Jemmy’s sympathizers, but by his creditors.

“Some rather startling disclosures in connection with the affair may be looked for,” the newspaper promised its readers.

It was then revealed, however, that the Jenny’s flight had been masterminded by her mate and her purser.

All the while Jemmy had been cooling his heels in a cell in the Bastion Square police barracks. With his ship in American custody, he had no choice but to take action. When the guard made his final round, Jemmy was hiding in an outhouse in the jail’s courtyard. In his bed was a dummy; once the guard had completed his head count for the night, Jemmy intended to make his way over the wall to freedom.

The guard glanced into the cell, saw the sleeping form and was about to proceed when it occurred to him that “It was rather a singular thing for a man to go to bed with his hat on.” (The slumbering form was also wearing a tie.) Entering the cell, he lifted Jemmy’s cap—to find that the debtor’s head was a loaf of bread.

The alarm was raised, the entire building and yard searched, and Jemmy found in the outhouse. He was returned to his cell after assuring the superintendent that he’d been “joking.” But, just three days later he was, to quote a laughing news account, “Gone from our gaze.”

Just across the Strait, Port Angeles, WA served as Jemmy’s temporary refuge from the law. —www.historylink.org/File/8210

From the safety of Port Angeles, Jemmy was pleased to inform Victorians how he’d flown the coop. Put to work in the jail yard with his fellow prisoners, he’d watched as the main gate was raised to facilitate their cleaning the entrance. Blocking his way to freedom were two guards, one of whom was armed with a revolver, the other with a double-barrelled shotgun.

“Now is my time...” Jemmy recounted. “I made a spring and passed the first man without being touched, the second made a grab at me, but I knocked him aside and ran past the Boomerang Inn and made the best of my way up Yates Street, several policemen following, and I think Tam O’Shanter and his grey mare ‘Meg’ were not more anxious to escape from the witches than Jemmy Jones and his legs were to outstrip the policemen.”

Outstrip them he did by hiding around a corner until his pursuers had passed.

By this time, of course, the alarm had been spread and he was faced with fleeing the Island, with police watching most points of departure. This, to continue Jenny’s gloating account from across the Strait, “puzzled me for a short time”. He decided to disguise himself. Upon changing into a dress and bonnet, he inspected himself in a mirror and “was perfectly satisfied” with his appearance.

Jemmy added, “I do not want to boast, but I think I fairly earned my liberty... I escaped in broad daylight by the aid of my own legs.” (And, it was rumoured, friends who transported him to Port Angles in a canoe.)

He concluded his “most amazing” account with a declaration: “I am Jemmy Jones, who will now make an effort to pay my debts and I ask for the confidence of my creditors in Victoria.”

Not content with this cheeky outrage, he returned to the city for his wife—and to buy a new suit.

“Verily,” snorted the Colonist, “Jemmy is too many for the myrmidions of the law in this quarter of the globe..”

(To Be Continued)

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.