Jolly Jemmy Jones, Our Most Outrageous Mariner - Part 2

Conclusion

We’re following the incredible story of one of the most colourful mariners ever to sail out of Victoria. Capt. Jemmy Jones has gone down in history as, of all things, a pirate.

For flying the skull and crossbones on the high seas? For robbing Spanish galleons of their golden treasures?

No, for “stealing” his own ship—twice—from the sheriff in Victoria, then from a U.S. Marshal. As we continue his tale, he’s just broken jail, is on the lam from Victoria police, and he’s about to make himself a wanted man in neighbouring Washington Territory...

* * * * *

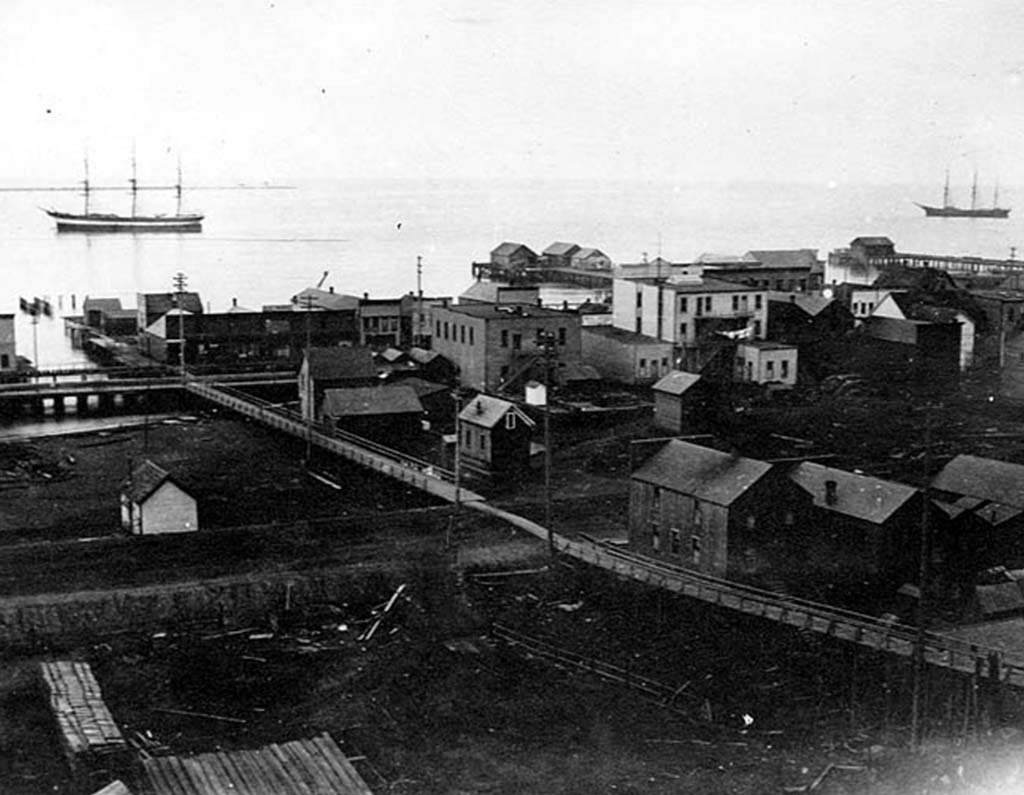

From Victoria’s sleepy looking Inner Harbour, Jemmy’s mate and engineer ‘liberated’ his schooner from the bailiffs and escaped to Port Angeles. —Author’s Collection

Also from the safety of Port Angeles Jemmy’s mate Charles Grainger wrote a letter denying the charges of piracy and giving his own, fanciful version of the flight of the Jenny. The Colonist printed the letter in full; Grainger wrote that the ship had been released from the sheriff’s custody when she cleared for Washington Territory to deliver U.S. mail for which she was chartered.

When a party Grainger identified only as “a self-constituted authority” boarded the vessel and attempted to take command in, in Grainger’s view, “defiance of all law and custom which govern the maritime service,” the mate had refused to comply. “I am a law abiding man [and] I felt it my duty to repel an effort which I considered illegal,” he wrote.

With Capt. Jones ashore “transacting some business,” Grainger denied knowing that he’d been arrested and the mate had “now found it...necessary to sail, as the time for the delivery of the mails is very strictly specified. I accordingly engaged a party to tow the vessel out of the harbour, as a portion of her machinery was defective.’

Grainger continued his preposterous account:

“After clearing the harbour, I observed several officers on board, and as I thought they had no authority to detain a duly cleared vessel, especially when she had the mail on board, “I politely requested them to go ashore.

“Seeing the justice of my demand, they readily acceded to my request, got into my boat and went ashore. There was no force or violence used whatever. The crew consisted of but seven men, and the immense amount of guns and pistols the Chronicle asserts as having been displayed to intimidate the officers, consisted of two mops, two brooms and one facet [sic].

“The two former, I am willing to admit, might prove formidable if not dangerous weapons in the hands of infuriated women.

“Now, Mr. Editor, this is about the substance of the matter, in a plain, unvarnished statement, and if you have any regard for your profession, you will have the kindness to show to the public your aversion for the contemptible style of collecting news—regardless of truth—whereby the interests of the innocent people are endangered, and the confidence of the public abused.”

On that noble note, Grainger “respectfully” concluded his version of the events preceding the Jenny Jones’s urgent departure for American waters. One can only conclude that Jemmy’s first mate missed his calling as a humorist.

Machinists Spratt and Kriemler, who made full claim for the Jenny by virtue of a mortgage, weren’t amused. When Rhys Gwynn, the Jenny’s engineer, returned to Victoria after having helped to spirit the vessel to Port Angeles, they had him arrested. In the dock on March 28, Gwynn faced the interesting charge of “aiding with other persons in creating a riot”.

After hearing the testimony of the sheriff’s men who’d been so rudely relieved of their command six weeks before, Police Court Magistrate Augustus Pemberton bound Gwynn over for a higher court, ruling that his case was far too serious for him to deal with.

A week later, Gwynn faced judge and jury—and a heavy sentence if convicted of any or all of the charges laid against him: conspiring to run away with the steamer Jenny Jones; riot; resisting officers in possession; and assault.

After all witnesses, including U.S. Consul Allan Francis (who testified that he’d advised Gwynn, who’d complained to him that he had back wages owing, to “go aboard and attend his business’) were heard, the engineer addressed the jury “in a very shrewd manner”. Fifteen minutes after retiring the jury returned with a verdict of not guilty.

Gwynn, after being warned by the judge not to associate with lawbreakers, was freed.

American authorities obviously regarded the escaped Jemmy Jones with respect for they moved his impounded steamer to Port Townsend then Olympia, intending to put her on the auction block at Seattle.

Jemmy arrived in Olympia just in time as U.S. Marshal William Huntington and a crew, including his own mate, Charles Grainger, were about to sail. When, in fact, the Jenny cleared port, she carried an unsuspected passenger—her own captain.

The state capital building, Olympia, WA.

Upon putting in at Steilacoom, Marshal Huntington, who seems not to have liked his shipboard accommodation, went ashore for the night. He left a deputy in charge of the ship—and a frantically scheming Jemmy Jones to a long night of little sleep as he plotted to regain his ship.

Morning bought a miracle.

The deputy went ashore to awaken Huntington at his hotel. This left Jemmy and Grainger in command. Deaf he may have been to the pleas and threats of his creditors, but Jemmy had a keen ear for the knock of opportunity.

Forty years after, the very proper, but obviously admiring, Capt. John T. Walbran described in his classic work, British Columbia Coast Names, 1592-1906, the challenge facing our hero: “With the U.S. officers of justice against him on one side of the boundary and those of B.C. on the other, with fuel* only sufficient for a 40-mile run, a solitary sack of flour, a few pounds of sugar and a pound or two of tea and no money, he cast off lines and sailed away.”

(*Although it isn’t mentioned in any of the news accounts, it’s obvious that the Jenny Jones’s missing engine room machinery had been returned to her so that she could be operated by the bailiffs.)

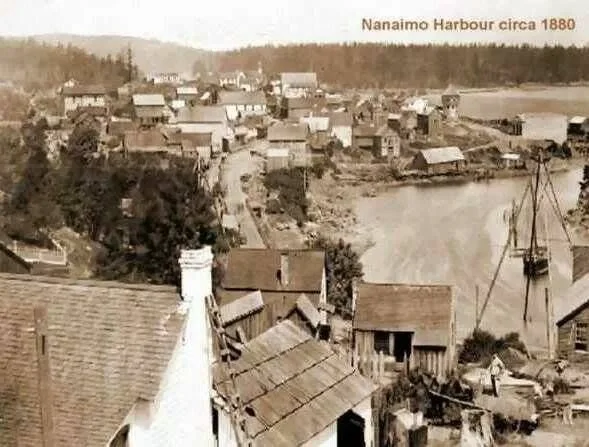

The fuel on board was enough to reach Port Ludlow where he scavenged enough cord wood to get him to Nanaimo, arriving just hours ahead of pursuing marshals on the commandeered sidewheel steamer Eliza Anderson. Nanaimo officials were uncooperative as he had no clearance papers from his last port of call, his most recent escapades were the talk of the coast, and merchants well knew his low credit rating.

At first, Nanaimo residents were sympathetic to Jemmy’s plight; years later, they’d change their minds about him. —www.pinterest.com

This likely would have been Jemmy’s undoing had not sympathetic citizens raised enough money by public subscription to allow him to purchase some supplies and sail to Newcastle Island where he engaged some Natives to load the Jenny’s bunkers with 12 tons of coal “dust” from an abandoned mine dump.

From the outset, both Victoria newspapers had chronicled the Jemmy Jones saga with less than journalistic objectivity. The Colonist obviously was a fan of the city’s very own pirate, following his activities with undisguised glee.

The Chronicle, to be contrary to its competitor, painted Jones in the darkest hues. Upon word that he’d been denied refuelling in Nanaimo, that journal gloatingly declared, “The indications are that Capt. Jones [has[ cooked a pretty kettle of fish for himself at last.”

The Chronicle underestimated its man. When overtaken by the steamer Otter in Johnstone Strait and asked where he was bound, Jemmy cheekily replied, “To Shanghai to load with live coolies for the British Columbia mines.”

Begrudgingly the Chronicle had to concede that he’d “shown his creditors a clear set of heels”.

Jemmy Jones, who faced a possible prison sentence of 20 years’ imprisonment if captured and convicted by U.S. authorities, was on the run, all right, but to sunny Mexico, not China.

Lady Luck again smiled on him. In the Gulf of Georgia (apparently he’d slipped across to the mainland for more cord wood to supplement his meagre coal supply), he encountered the sloop Deerfoot. Holds brimming with provisions to trade, she was en route to Stikine country. She had, however, developed a serious leak and was in need of assistance.

Ever gallant, Jemmy took her in tow but it was soon apparent that she must founder. Inspired, Jemmy explained to her owners that he was off to strike it rich in Mexico and invited them to join him.

Whether because of his eloquence, enthusiasm—or the threat of being left to sink—the three traders agreed to accompany him to Mexico. The hapless Deerfoot was stripped of all goods and left to her fate. (She subsequently drifted ashore and was salvaged after creating fears her company had been murdered by Natives and prompting the government to dispatch the gunboat HMS Forward on a fruitless manhunt.)

HMS Raven, a gunboat of the Albacore Class, similar to HMS Forward which served in B.C., waters as a police vessel. —military-history.fandom.com/wiki/HMS_Forward_(1855)

“Thus well manned and equipped,” Cap. Walbran continued, “the Jenny Jones made for the open sea, passed through Johnstone and Broughton straits, called at Fort Rupert and Kyuquot, and with steam and sail helping her along, arrived at San Blas, Mexico, after a voyage of 25 days.

“Here Capt. Jones paid the men their wages, and also allowed hem $625 for the sloop and her cargo. He subsequently obtained a profitable freight for Mazatlan, and on reaching that port his crew again pressed him for money. One of the men from the ship claimed $1000, and made application to the U.S. Consul to have the vessel seized and his demand was acceded to.”

Lest Jemmy consider sailing away as he had at Steilacoom, some untrusting soul unshipped and hid the Jenny’s rudder.

But the accusing seaman couldn’t verify his claim that Jemmy had fled the marshals and his application was dropped. However, Jemmy had at last become disheartened by the constant litigation and sold his ship to Mexican interests for $10,000.

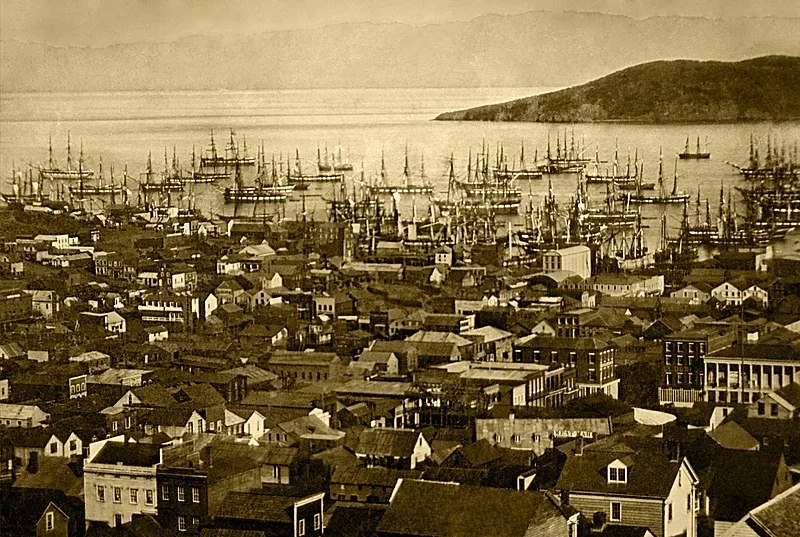

Unencumbered and enriched, Jemmy headed for the bright lights of San Francisco—and right into the waiting arms of the law. Fortunately, his spirits had revived and he met this latest disaster with his old fire and wit.

Hauled before a judge, he vehemently protested that his ship hadn’t left the marshals at Steilacoom, as charged, but that Mr. Huntington and his deputy had left his ship! Which was the truth, after all. The understanding judge replied, “Not Guilty,” and he was freed. Later tried on the same offence at Steilacoom, he was again acquitted.

San Francisco, Jemmy’s last port of call in his flight from the U.S. marshals. —Wikipedia

Thus ending what must be one of the few cases of piracy in B.C. maritime history.

At least so far as Jemmy Jones was concerned. He may have been able to wash his hands of the affair but the Jenny Jones drama continued to haunt some of the supporting actors. U.S. Marshal Huntington, who’d forsaken the ship’s spartan accommodation, and his duty, for a hotel room, thus enabling Jemmy to steal her back, was sued by Messrs. Spratt and Kriemler, and other creditors, for “culpable negligence and malfeasance in office...”

The plaintiffs won their suit in the amount of $2000.

Three years later, Jenny’s engineer, Charles Hughes, made the mistake of setting foot in Washington Territory, perhaps thinking American authorities had forgotten him. Convicted of “felonious abduction of the steamer Jenny Jones while in the custody of the U.S. Marshal,” he was sentenced to four years’ imprisonment and $2000 fine—his sentence to be halved, and the fine forgiven, if he reimbursed Marshal Huntington!

When, ultimately, Jemmy returned to the Island, he was all but broke but his debt was said to be “forgotten or condoned”.

He tried a stint of coal mining and again made news, almost five years later, when charged with being drunk and using threatening language. Pleading not guilty, he tried to convince the court that the arresting officer was mistaken. He “walked crooked,” he said, because his boots were new and hurt his feet; he “talked crooked” because he’d taken a dose of castor oil which had loosened his tongue and lost him control of it”.

(Jemmy seems to have learned something of creative licence from his mate, Grainger.)

Tongue firmly in cheek, the magistrate fined him five shillings for wearing new boots and ordered him remanded in custody for a day, that the “effect of the oil may be noted”.

“Poor Jemmy,” laughed the Colonist when reporting that the purgative effects of the castor oil hadn’t manifested themselves and he’d been ordered to post bond to be of good behaviour for a year or suffer another six months’ imprisonment.

In 1873 Jemmy was in command of the 63-foot schooner Industry and almost lost her in a gale in the Strait of Georgia. Three years later, he temporarily forsook the deck of his ship for a soapbox from which he delivered a “mellow and melodious” 90-minute long assault on the politicians of the day—until a bored listener threw a duck egg. The critic’s aim was true and “the modern Cicero...sought a bucket of water and a tablet of soap and subsequently, we hope, his bed”.

Always one to mix business with pleasure, he rented, for an honorarium, a hall in Nanaimo to sell some goods, having agreed to relinquish the premises if they were let for full rental value. When a theatre troupe tried to book the hall, Jemmy, who’d been on a week-long “rampage,” refused to vacate.

Sheriff’s officers with an eviction warrant were denied entry, only managing to serve their summons by lowering a delivery boy down a ventilator shaft!

An enraged Jemmy was off to Victoria to seek legal damages from the hall managers in the amount of $5000.

By this time even the Colonist was losing patience with its hero, terming him an incorrigible nuisance for his latest antics in Nanaimo where he’d hitched a ride in a bucket of the Harewood Mine’s aerial tramway, only to find himself stranded in mid-air, at the intersection of Albert and Wallace streets, when workers stopped for lunch. A crowd gathered, names were called and Jemmy replied with flying coal chips.

Three of the tramline towers that linked the Harewood Mine to Nanaimo Harbour. Note the bucket hanging from the cables; it was in one of these that Jemmy hitched a ride only to find himself marooned in mid-air. —www/geocaching.com

Mine officials had hoped his aerial delay would discourage him from continuing but they little understood the man who’d thumbed his nose at British and American law.

Forcefully evicted from his bucket, he made a second attempt to board the tramline before being run off, to make a further nuisance of himself during Mayday festivities. Only two weeks later, he was brought to Victoria in handcuffs, bound for the city’s lunatic asylum after having been pronounced insane by a medical doctor.

During the voyage from Nanaimo he’d amused himself with a child’s whistle.

Within a week, he was free, committal to the asylum requiring certification by two doctors; apparently a second signature wasn’t forthcoming. He had, reported the newspaper, promised to behave himself and the Colonist wished him well.

His resolve lasted less than a month. Back to terrorizing Nanaimo, he led a parade of sailors from ships in the harbour through city streets, waving the Stars and Stripes to the accompaniment of accordions, penny whistles and singing. Nanaimo residents were said to have been less than amused.

His misadventures at sea continued, Jemmy barely escaping with his life when the schooner Industry was swamped off Trial island. Between accidents he managed to transport Nanaimo sandstone to New Westminster for use in the building of the new federal penitentiary.

He also commanded the collier Discovery and sank her. Upon her being re-floated, he bought the hulk for a trifling sum and returned her to service.

In August 1882, the illustrious saga of Capt. Jemmy Jones came to a close in the Jubilee Hospital when his “naturally hardy and strong constitution,” undermined by a lifetime of hard living, gave up at age 52. He left a widow confined to an asylum and two children.

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.