Louisa Townsend of the Bride Ship Tynemouth

Long before the famous war brides of the Second World War there were the brides of colonial days; young British women, aged 14-20, who sailed halfway round the world to “the colonies” in hopes of finding husbands.

The Tynemouth was the largest of the bride ships used to transport prospective brides to the British colonies. —www.pixabay.com

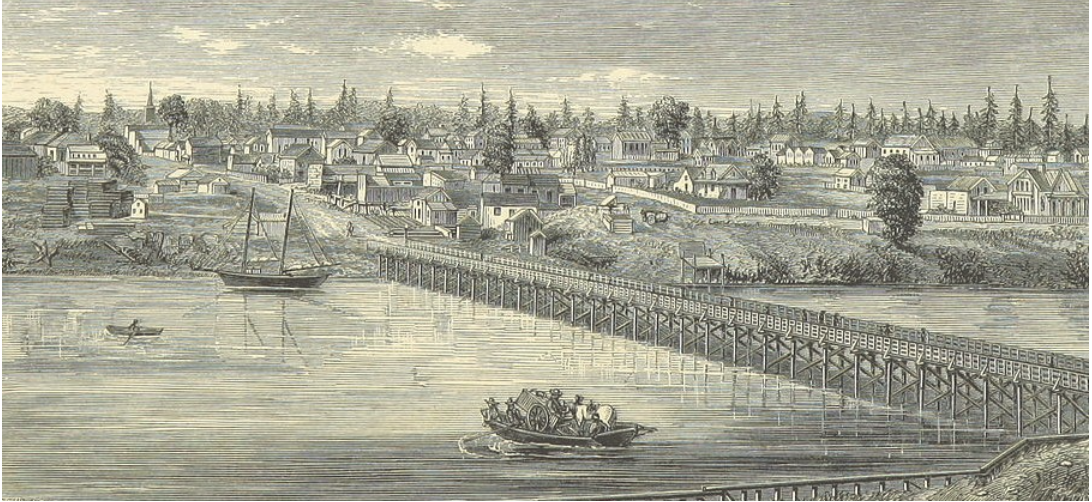

Those who landed in Victoria’s Inner Harbour in 1862 were, in the words of one of their own, “an odd assortment of females”.

* * * * *

A century ago, Mrs. Edward Mallandaine (nee Louisa Townsend) vividly recalled the historic and exciting voyage ’round Cape Horn to Fort Victoria with her sister and 58 other young women.

By the time of her interview in the spring of 1924, she was almost 93, widowed and living alone in a little cottage amid a large, old-fashioned garden in Victoria’s James Bay—within blocks of where she’d landed from the sailing ship Tynemouth in September 1862.

Confined to a wheelchair for six years, the attractive nonagenarian, of whom it was said that she didn't look a day over 60, delighted in receiving visitors. Her hair, “once a marvel of luxuriousness,” was yet thick and retained its original hue with only a sprinkling of grey.

Her cheeks glowed pink, her eyes sparkled as she spoke, and it didn't take any imagination to realize that she'd been a beautiful young woman (a fact that she modestly denied although her friends were quick to confirm it). In fact, both she and her sister had been beauties and, it can be imagined, more than welcome arrivals aboard the Tynemouth.

For that matter, not one of the blushing quote “brides” had failed to receive a warm welcome upon the ship’s arrival in Victoria. According to the record, the landing of the Tynemouth ladies “aroused greater interest” than any ship before or, perhaps, since.

Victoria bachelors feared that American miners would hijack the Tynemouth’s cargo en route. —BC Archives

White women were few and far between in the colony in 1862 and the ship’s impending arrival had been anxiously awaited by 100s of prospective grooms who’d flocked to Victoria from throughout the Island and Mainland B.C. When it was rumoured that, upon the Tynemouth’s calling at California while en route, attempts would be made to “steal some of the young women... there was much anxiety expressed here that the whole of the expected 60 might not reach Victoria”.

Fortunately for the waiting and near-frantic bachelors, the special agent in charge of the ship’s fair cargo exercised great pains to see that none of the ladies left the ship at any port of call for any reason, with the result that, upon its eventual landing in Victoria, the Tynemouth carried a full complement.

“It was a good ship,” Mrs. Mallandaine reminisced 62 years later, “and my sister and I had nice quarters, with our visiting cards, ‘Miss Charlotte Townsend and Miss Louisa Townsend,’ tacked above them. I think we were the only women on the boat that possessed such a thing as a visiting card. They were for the most part an odd assortment of females...”

Back in the Old Country, the Townsends had forsaken “a lovely home and kind parents” for the unknown. “We were taught what all properly brought up young girls were supposed to know in those days [including] music and French. We had never had to do domestic work, and when at last our relatives consented to let us come out to Canada, we thought we would find most of the comforts of home and would be able to teach French and music.”

Mrs. Mallandaine’s parents had arranged for her to stay temporarily with the daughter of a friend of her mother's “as a sort of companion”.

This woman had come to the New World years before and married. Both sisters were “very much excited at the prospect of sailing almost around the world and meeting new people and living in a strange land”.

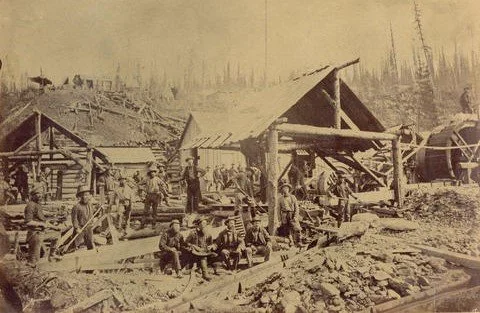

The 60 brides weren’t the only passengers aboard the S.S. Tynemouth; most of the younger male passengers were headed for the Cariboo gold fields. —BC Archives

Much to their delight, they found the Tynemouth to be fast and comfortable despite the fact that more than 300 passengers had booked for the voyage. Most of the male passengers hoped to to make their fortunes in the new Cariboo diggings. “Some of them did, I've no doubt,” she said.

She remembered the tender “taking us to the steamer, saying goodbye to my older sister and seeing the shores of England fading in the distance... "

Neatly packed away were the sisters’ “beautiful trousseau” that their aunts and older sister had helped them to make. There were fine lingerie, “dainty” dresses, hats and boxes of handkerchiefs and lace “mitts,” a piano, sewing machine, music and schoolbooks.

“The very first night out, we had a terrible storm and the ship’s cow got washed overboard. This was very serious because we had no milk. I was very ill on the ship. I could not eat the fare. The captain was afraid I might die. The ship’s doctor looked after me and the officers were all very kind. The captain had special quarters prepared for me, and delicate food. After a week or two I was better.

“When we reached California, although some of us would have liked to go on shore, we were not permitted to do so, and we did not set foot on land until we anchored out in the Royal Roads, and the little boats brought us to the wharf near where the James Bay boat house is now. I remember that great tubs of water, hot and cold, and plenty of soap had been placed in readiness in front of the old Parliament Buildings, in case we had linen that we wished to wash at once.

“Some of the women had but my sister and I were in no such need. We had worn our oldest things on shipboard and put them through the porthole when we finished with them. So we arrived in new garments, with trunks full of lovely things... "

Louisa and Charlotte were quickly hustled off to their temporary quarters in the Royal Marine barracks. Half of the ship’s female company had been engaged as servants and soon took residence in their employers' homes. Although Louisa made no mention of a welcome reception, the Colonist noted that “a large and anxious crowd of breeches-wearing bipeds assembled to see the women disembark and expressed themselves as well pleased with their appearance”.

Another Victorian who was ready for the occasion was the merchant who’d advertised the sale of men's clothing, no doubt anticipating a rush on the latest in fashion as 100s of hopeful bridegrooms tried to look their best so as to improve their chances with the lovely arrivals.

Soon after her landing in Victoria, Louisa was introduced to Mrs. Pringle, the woman with whom she would stay, and was hurried off to her home on the Mainland.

She couldn't remember, 62 years later, the name of the little community [likely the Royal Engineers’ Sapperton], it was somewhere beyond New Westminster and I know that there were a lot of soldiers and that we were never allowed to go out on the street alone.”

While at Sapperton, Louisa and other young women were warned against going out alone. —Vancouver City Archives

Asked what her immediate impressions of her new home had been, Mrs. Mallandaine sighed that, having been led to believe that life in the colony would be much like that in the Old Country, she was truly disappointed.

“No, I was not happy and I saw nothing beautiful about it. From the very first I was disappointed. One of the things that the people seemed so proud about was the fact that the gas [lighting] had just been installed [10 days before their arrival]. They kept constantly calling my attention to it.”

Far from being impressed, she thought the future provincial capital “very badly lighted...and the rain and the mud were dreadful. When we went to church, we had to carry along little sticks and put them down in front of us to step on or we should have gone in over our boots”.

For three long, lonely months she stayed with the Pringles, crying herself to sleep each night.

The house, she said, was a miserable one, and her room was like a garret with big cracks that let in the rain. Although there was a Chinese houseboy there were “tasks to do that were very distasteful to me, because I had been brought up with servants in the house and all sorts of comfort and luxuries”.

One of her more frequent duties, curiously, had been playing the community’s one and only piano. As no one else played well, she was frequently called upon to entertain at social functions.

1860s Victoria was such a major disappointment for the gently raised Louisa Townsend that she cried herself to sleep every night. —BC Archives

Once, her varied wardrobe had led to an intriguing encounter on the street when she was stopped by a passing girl whom she knew only slightly. The girl was about to be married and, captured by Louisa's pretty dress—“much prettier than anything I have”—she asked her to be her bridesmaid.

The startled Louisa agreed but, on the on the momentous day, realized that she wouldn't be able to attend as she’d promised. When a young man, acting for the bride, called at the Pringle house to find out what had happened to her, he found her crying.

Ignoring her tearful explanation, he “bundled me off, and when we reached the home they were waiting the wedding breakfast for me.”

Another interesting highlight of colonial life was that, daily, soldiers and marines stationed nearby would find reasons to walk by the Pringle home, passing again and again in less then subtle attempts to catch a glimpse of the attractive young woman at the window.

And a successful miner passing through town with a bottle filled with nuggets, asked her to marry him.

After three months with the Pringles, her fortunes improved when she returned to Victoria to serve as a companion to the invalided Mrs. Pidwell, whom she described as “very sweet and kind, and I used to teach her two little daughters. They were naughty. They did not want to learn. I had my hands full with them. The Pidwells lived where the old YWCA home used to be, on Humboldt Street.

“They entertained a lot. I remember when Mr. Pidwell was killed. He was driving out to Esquimalt and ran into the high rock that used to jut out into the road. He was killed almost instantly.”

In Victoria, she was able to ride horseback, having learned to ride in England, and she enjoyed playing cricket although her favourite pastimes were the piano, singing and dancing.

After working for Mrs. Pidwell, she joined the Rhodes household at Maplehurst where she could indulge in singing and dancing almost regularly as the Rhodes entertained often, with numerous naval and army officers in attendance. It was at one of these social affairs that she met Edward Mallandaine.

(It should go almost without saying that not all of the 60 prospective brides aboard the Tynemouth fared so well in B.C. as Louisa Townsend/Mallendaine.)

Ninety-three at the time of her interview by a Colonist reporter, by then the mother of five, she’d been widowed for 19 years and was, it turned out, within a year of her own passing. In 1924, both she and sister Charlotte, who’d accompanied her as a prospective bride, remained as close as as ever.

Her focused memories of the importance of her appearance suggest both vanity and shallowness, even, perhaps, a sign of dementia. Or, more charitably, just her choosing to recall what were for her the highlights of her cosseted youth.

“I remember the first time I went to Government House,” she recalled. “They said my dress was the prettiest there. I bought a whole bolt of tarlatan, and I made it in three rows of scalloped ruffles, with a broad white satin girdle. It was decorated with variegated geranium leaves. We wore crinolines then. I had a glorious time at that dance. I was not engaged but, Mr. Mallandaine had invited me to go there with him.

“Afterwards, I had a standing invitation to go to Government House every Friday afternoon.”

It was at a St. John's choir practice that she’d met Edward. A young widower, architect, publisher of Victoria's first directory, schoolmaster and son of a former governor of Singapore, Mallandaine had arrived in Victoria when it was just a ‘tent city.’

He fell in love, he told her, with her beautiful hair. By that time she was living with her sister Charlotte who’d married a Mr. Townsend, thereby keeping her maiden name. When he popped the question, and she consented, both agreed to keep the forthcoming marriage a secret so as to avoid any “fuss.”

They kept the secret so well, in fact, that upon Edward informing his future sister-in-law the morning after the event, she was “thunderstruck” and, according to Louisa, quite disappointed as she'd have preferred a large wedding.

“The next morning,” Louisa recalled with a smile, “I donned my new clothes, a dainty muslin dress, a large hat with tremendous white feathers down the side, and overall a beautiful white alpaca coat. We walked along Douglas Street and it was very quiet, one old man being the only person we saw. Mr. Redford, who came out on the Tynemouth, was the best man.

“That afternoon I went shopping, so you see I was very practical. Our new home was up at the top of View Street. The house is still standing. That was 60 years ago nearly.”

By 1924, Mrs. Mallandaine was a mother five times over and a widow, Edward having died in 1905. As always, she had her sister Charlotte who lived nearby, and who remained active. Even after their marriages, they’d remained close. As Louisa’s interviewer concluded, 101 years ago: “The two sisters are a remarkable pair. They have never been separated, and have grown old together. Their reminiscences would easily fill a volume and cover the most romantic period in the history of British Columbia.”

The Townsend sisters were finally separated upon Mrs. Mallendaine's death, within a year of her interview, at the age of 94.

* * * * *

The story of Louisa Townsend/Mallandaine, just one of the 60 young women of varied backgrounds, most of them orphaned or impoverished, who sought a better life by sailing aboard the Tynemouth, is one of privilege.

Not for her the hardships of frontier life, not even when aboard the ship where, according to one historical account, most of the brides were “treated as little more than cargo, stuffed into the bottom of the ship with inadequate food and poor sanitation. Many became ill during this journey of nearly 100 days...”