Love Came Too Late for Beautiful Belle Castle

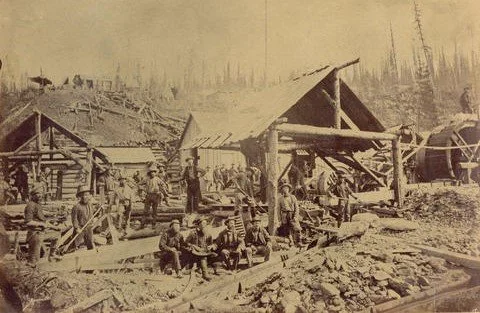

From around the world, they came to Cariboo in search of gold. A lucky few struck it rich; most had to settle for workman’s wages or return home, broke and disappointed. Single women had few choices other than to serve as cooks or hurdy gurdy (dancehall) girls. Belle Castle dealt cards. All of them had stories to tell... —BC Archives

Her real name and where she came from, no one knew. But that she’d been beautiful and a lady, all were agreed. Upon her death in a lonely B.C. mining camp, forsaken by all but the man who loved her—and the rose tree she’d nurtured and cherished with a mother’s devotion—her secret went with her to the little cemetery on the hillside.

Today, even her grave site is unknown and the mystery of Belle Castle, as she called herself, remains safe with the ages.

* * * * *

Barkerville, 1868. Journalist D.W. Higgins who first told the story of Belle Castle in a series of stories and reminiscences he wrote for the Victoria Colonist that were later published in two books, The Mystic Spring and The Passing of a Race, identified the locale as merely ‘Williams Creek,’ rather than one of this fabled stream’s three historic town sites, Richfield, Barkerville or Cameronton, a mile downstream from Barkerville. —BC Archives

She first appeared in the roaring boom town of Williams Creek in the spring of 1862. In the company of a gambler named Castle, whom she introduced as her husband, she immediately caught the eye of the townsmen. Women of any class were a rarity in the gold camps but Belle Castle as she called herself would have stirred interest anywhere.

Tall, with flowing black tresses streaked with grey, her graceful carriage and gentle manner betrayed a past of a considerably higher social scale than that of the miners, gamblers and hurdy gurdy girls with whom she and her husband consorted.

Castle himself, a faro and three-card monte dealer in one of the saloons, shared none of his wife's charm or grace, making Belle's reserve all that more apparent to the men who met her in a bar room. It was this gentility and her warm smile—even when the bank was losing—that drew an increasing number of miners to the Castles’ gaming table.

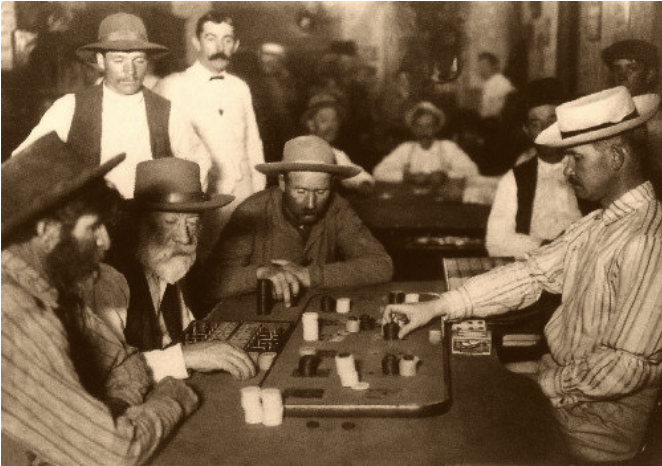

All eyes are focused on this faro game somewhere in the American West. Gambling for big stakes was popular with many miners in the Cariboo, particularly those who’d struck it rich, but women dealers were scarce. Beautiful Belle Castle was the exception—and her beauty and Madonna smile drew the serious players to her table. —Wikipedia

Although she only spoke when necessary, their table became the most popular in town and the money began to pour in.

Night after night, with the grandeur of a queen before her court, Belle shuffled and dealt the cards with natural ease. Win, lose or draw, her expression never changed; none who tried his luck could penetrate the mask behind that permanent smile. When, as usually was the case, the bank won, the loser would leave the table without a murmur of complaint.

To play with Belle—and to lose—became something that was almost expected of any miner worth his salt.

Two months passed, the Castles raking in pot after pot, but for the odd evening when one of the gambling miners would walk away a winner (only to lose it, and more, in a return bout). But, try as they might, none can get Belle to give them anything more than her Madonna-like smile.

About the same time that the Castles arrived on Williams Creek, the camp welcomed another remarkable arrival in the form of Tom Edwards. Born an English gentleman, he’d early forsaken family wealth and position when, after a bitter quarrel with his father, he’d joined the Royal Navy as a midshipman. He attained the rank of sub-lieutenant before deciding to join the throngs of fortune seekers en route to B.C.'s golden Cariboo.

By that time, there was little evidence remaining of his genteel past. Although formally educated, he’d long surrendered to the common speech of seamen, preferring a mild form of profanity to the correct English usage of his childhood. His favourite expression, according to one who knew him, was “bloody”. To him, a man was either a bloody good fellow or a bloody fool. If he heard a sermon, it was either bloody fine or bloody not. A meal was bloody good or it was bloody bad...

Hence he became known to one and all as “Bloody Edwards.”

At Williams Creek, his genial disposition and devil-may-care attitude made him a ready favourite among his fellow adventurers. In that reckless age, when fortunes could be made and lost overnight, Edwards’ obvious joy for life made him a natural leader, particularly in the evenings when the miners, their pokes bulging with dust and nuggets earned at the risk of life and limb in the daytime, would elbow their way to the bar for a night of heavy drinking, games and fellowship.

Belle Castle stood out from the usual hurdy gury girls shown here who made their living by cadging drinks from successful miners. —BC Archives

Not unnaturally, the saloons and dance halls did a thriving business. As one witness recalled half a century later: “In every saloon there were tables at which sat professional gamblers. Most of them were men and a few, alas! were women who, when they entered the [saloons], left their good names behind. In the dance houses were a number of females who rejoiced in the titles of hurdy gurdies. They were paid to steer their half-inebriated partners, after each dance, to the bar and induce them to treat at 50 cents of glass.

“These girls appeared to possess unquenchable thirst. They consumed large quantities of beer, wine and whisky but were seldom incapable of taking care of themselves. The gold commissioner of the day refused to interfere with gambling and the establishments applied the trade with a brazen indifference to decency and law.”

It was in this world of hard work, physical danger and debauchery that Bloody Tom Edwards (half a world and half a lifetime from title and home) met the lady with the enigmatic smile, Belle Castle.

* * * * *

“We are not much on style here. We cut out all the bloody society talk and come right down to hard-pan and bedrock in our own bloody language. There's no bloody sense in putting on airs or making believe that we're at home when we’re nobody here. A man's past counts for nothing in Cariboo. All we want to know is what a bloody fellow is, not what he was.

“Who would ever think to look at me, or hear me talk, that my father was a British admiral and that I had once been an officer in the Queen's bloody navy? No one...”

So said single ‘Bloody’ Tom Edwards, one of the 1000s of adventurers who’d found himself on Williams Creek in 1862 where he quickly became a camp favorite.

Miners had to be tough on the B.C. frontier so it shouldn’t come as a surprise that some of their sports, like cock fights and dog fights, were also a fight for survival. Bloody Tom Edwards was sure to be among those involved whenever there was such a contest, always placing hefty bets on the outcome.—istockphoto.com

Whenever there was an injury, it was he who rendered first aid. When death struck and a clergyman wasn’t available, he read the service with professional aplomb and without his usual profanity. When there was a prize fight between the Surrey Chicken and the Boston Pug, it was Bloody Edwards who served as second to one of the pugilists. When the local pleasure turned to dog and cock fights, he was sure to own one of the four-legged or feathered contestants.

Between these activities, he found time to make his stake. It was then, with heavy poke, that he began to frequent the gaming tables, particularly that of the enigmatic Belle Castle. Night after night, Tom took a seat before the smiling dealer, to recklessly risk his gold on the turn of a card. How many times Belle fingered the cards with almost fluid grace, no one could recall. How many times the beautiful dealer raked in the pot, only Bloody Edwards could say for sure, although those who watched the contest from time to time were aware that he was losing steadily.

But Edwards never complained and, ever so slowly, those who followed their nightly dual became aware of a growing affinity between the hard-drinking, hard-playing miner and the lady with the maddening smile.

The more observant noted that Belle always addressed Tom as “Mr Edwards”. Even more apparent were Bloody Edwards’ attempts—usually futile—to drop from his vocabulary the offending adjective that had won him his nickname.

Making his rehabilitation all the more painful was his friends having taken to teasing him unmercifully about his “romance” and, as they clustered about the table, purposely loaded their speech with “bloody” this and “bloody” that. As Edwards squirmed in embarrassment, much to his comrades’ delight, Belle merely smiled and dealt the cards. When Tom did regain his composure and his wit, the evenings were enlivened by their repartee.

Throughout these months, Belle's passion, a small rose tree, stood behind the bar amid the rows of bottles and glasses. Guarded with “a lover's jealous care,” the bush thrived in the stale, smoke-filled and dingy saloon, and became a source of constant wonder to the miners and dancing girls who watched its progress with almost as much attention as its owner.

Finally came the momentous day when tiny buds appeared. Word swept the town.

Every man and woman made the pilgrimage to the saloon, just to stand in awe before the budding bush in its surroundings of human decay and debauchery. Throughout the “birth,” Belle stood guard over her prize like a mother hen, gently declining all requests for a blossom.

But, each and every Sunday thereafter, Bloody Tom Edwards appeared with a fresh red rose in his buttonhole, and “heads were wagged and wise looks exchanged”.

When the more outspoken asked where he obtained the flower, if not from Belle's “garden,” he merely smiled.

Summer passed, then autumn, and the first snow of the year shrouded the hills. This was the annual warning to residents that it was time to head for the gentler climate of the coast until spring returned to the Cariboo, and preparations for the mass exodus were begun.

Among those preparing to leave were the Castles, rumors having circulated town that they’d sent a formidable sum of money ahead by express. Be that as it may, they bought their tickets for the next stage, packed up their belongings and paid their bills.

They were in the act of bidding farewell to friends when Belle became ill. She was put to bed with a sore throat, a doctor was called and, upon examination, she was given the grim diagnosis: diphtheria. Sometime before, Belle had nursed a woman who’d died from the same symptoms and Belle was pronounced to be in an advanced stage.

Diphtheria!

Word of Belle's illness swept Williams Creek. Dreaded even more than smallpox, the very word was enough to create panic and, overnight, the camp became a ghost town but for a handful who dared to remain a while longer to wrap up their affairs.

Even her so-called husband, after depositing a sum of money to cover her care, abandoned her side. When he boarded the last stage, a frightened hurdy gurdy occupying the place that had been reserved for Belle, he cringed in his seat amid the jeers of derision and contempt uttered by miners disgusted by his faithless flight.

Then Belle was alone. None dared nurse her as to do so virtually guaranteed their own illness. None, that is, but bloody Tom Edwards, the errant son of a British admiral whom Belle had always addressed as Mr. Edwards as she relieved him of his gold at the game table. When told of his presence, she at first refused to see him, urging the doctor to send him away lest he too, catch the pestilence. But Tom refused to leave and, over her protests, entered her sick room.

Despite the dim light, his eyes were immediately drawn to Belle's beloved rose tree, that which had bloomed almost in spite of its smoke-filled saloon habitat, and which had been placed on a shelf beside her bed in such a way that she could see it without turning her head.

Of the many blossoms which had bloomed in the summer, but a single red blossom remained. Bigger and more luxurious than the others, the surviving flower seemed to strain upward, as if offering itself to its ailing mistress. Whenever Belle woke, her first glance was towards her rose, and Edwards would carry it to her bedside, that she might inhale its fragrance.

For all of Tom’s loving care and the attentions of two physicians, Belle failed steadily.

Her face was distorted with pain, her long, luxurious tresses became tangled and unkempt, and her quixotic eyes glowed with an unnatural fire. Her forehead grew hot to his touch and her periods of consciousness became fewer. On the second day, Tom was advised to tell her that she was dying.

He received the verdict with a groan but numbly obeyed.

Upon entering her bedroom he found her to be asleep; when she did awaken, she called him to her bedside to tell him that she’d had a dream in which she’d seen herself in a coffin, that he'd been her only mourner. “Oh, Tom, I have to go just when I wish to stay.”

As the one-time gentleman, seaman and miner fought back his tears, she placed one of his calloused hands in hers and kissed it, then drew him gently down beside her. Placing a frail arm around his neck, she whispered, “Tom, I was not always what I am. Once I was as pure as the lovely rose that blooms on yon shelf. Who I was no one will ever know. My secret shall die with me. A dear mother and brothers and sisters in far away England watch for my coming with straining eyes and watchful hearts.

“But they will watch and hope in vain. They will never see me again. I have been wicked, Tom, and I am paying the penalty. But for your faithful heart I should have died alone—deserted in this wilderness of sin and wretchedness. Many times I have wished myself dead and now I would like to live for your sake. But it is too late.”

Suddenly, she drew back, apologized for having being so unthinking that she could have been infected him, and ordered him away from her bed. For several long minutes there was silence. Then Belle asked him to bring her the rose. She clutched it to her breast as a mother would her babe, kissed its leaves and caressed its branches as tears streamed down her cheeks. She then asked for her Bible and upon Thomas passing it to her, he noticed the brief inscription on its flyleaf: “Belle, from her mother, on her wedding day. Preston, Aug. 24, 1847.”

At her direction, he read a passage, when she again drew him near, to ask that the rose be placed upon her chest and that it be buried with her. When he nodded, she lay back upon the pillow and appeared to sleep peacefully.

Then Tom, too, dozed off. Upon being awakened, he was told that Belle was gone. When he glanced at the rose, he was startled to see that its last petal which, only minutes before had been brilliant red and vibrant with life, lay blackened and wasted at the end of its stem, and as dead as its mistress.

That afternoon, they carried Belle to the little cemetery on the hill. Accompanying her inside the crude coffin of pine were her Bible and her blighted rose.

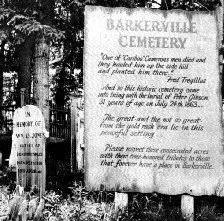

Higgins’ reference to “a little cemetery on a hill” doesn’t fit the Barkerville/Cameronton cemetery. —BC Archives

Half a century later, journalist D.W. Higgins, who’d known both Belle and Tom, noted that the headboard erected to mark her grave had rotted away, “Bloody” Tom Edwards had gone to his own grave, and “none ever solved the mystery that enveloped the career of the late Belle Castle”.