Nathan Dougan, the First Cowichan Chronicler

(Conclusion)

Two weeks ago, I introduced you to N.P. Nathan Dougan, Cobble Hill and area’s foremost historian, and his son, Bob, who carried the torch until his death in the 1990’s.

Logging with horses and oxen on the Castley farm, Sathlam. —R.I. Dougan photo

Both Dougans contributed greatly to the saving of Cowichan Valley history, beginning with Nathan’s articles that appeared in the Cowichan Leader in the 1950’s and ‘60’s. Bob condensed and published many of these ‘narratives’ as the Leader called them in Cowichan My Valley, now a rare and valuable book.

This week, in Nathan’s own words, the second half of “In the Days of the Hand and Bull-Team Logger” which was originally published in December 1949-January 1950.

Without Nathan Dougan none of the following information would ever have been recorded and thus been saved for posterity. Any newspaper references of those early days are sketchy at best.

What Nathan hadn’t observed firsthand he likely gained through conversations with some of the surviving participants. History doesn’t get any better than that.

So, back to Nathan Dougan:

* * * * *

Nathan Dougan, looking distinguished in Sunday suit and tie. —Family photo

Handsel Vickery came to Cherry Point in the spring of 1908 and acquired possession of the land now owned by Col. Lewis and others, and with Mrs Vickery made his home in the old log house that had been built by one Hazenfratz.

Vickery had been logging at Sooke; hauling logs into a creek expecting a rise of water to carry them to the beach. The rise did not did not occur; and the logs stranded there, a total loss (or so he told me).

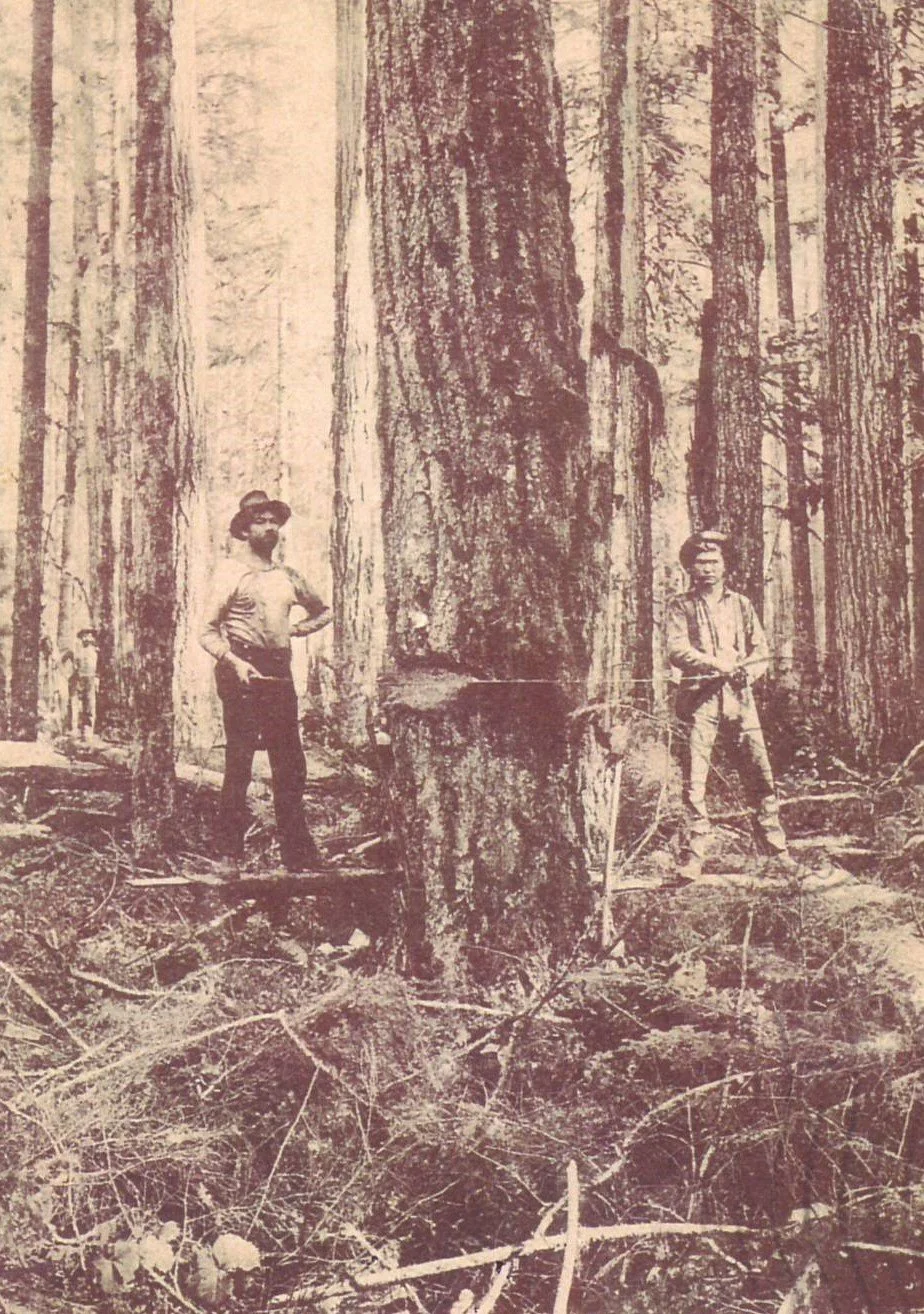

Everything about logging in the so-called good old days was work—hard work. —Author’s Collection

When he arrived, he was impecunious, but certain merchants carried him on credit. Hearing that John Spears on the [Cowichan Bay] flats had a pair of steers for sale, he went to him and was able to buy them on his notes. He brought them home and during the night they broke away and morning found them back on the flats. He brought them home again and yoking them together soon had them drawing small logs.

On credit he was able to buy a heavy four-inch-tired logging truck—these trucks were specially made for oxen or horses—and with the help of a couple of Chinese labourers, cut on the Cherry Point Road near its intersection with Telegraph Road, his first boom of logs and truck them to the beach with his yoke of oxen.

[This was my ‘backyard’ for the 20 years I lived on Cherry Point Road, just two properties up from what’s now a winery, and three properties down from the intersection of Cherry Point and Telegraph roads where Vickery, 60 years earlier, first logged. In my time, Fred Dougan lived at the intersection and brother Bob three properties farther along Telegraph Road in the old family home. —TW.]

After this beginning, Vickery was able to buy another yolk or two of oxen, and on another section of land, carried on skid-road logging for some years. He received an average price of $8 per M. and paid $1 stumpage.

A team of horses hauls a string of peeled logs (so they’d slide easier). —R.I. Dougan photo

JOHN MACPHERSON

And then there was the late John MacPherson, father of Mrs. Jean and John MacPherson, Duncan, who logged with [William] Sayward with oxen on Valdez Island for years; later taking a foreman's job at Sayward’s mill [Mill Bay], and finally returning to his farm near Riverside Road in the early 90s, where he lost his life about 1912 when attacked by a vicious bull.

About the conclusion of the Great War and into the early ‘20’s there was in this Cherry Point locality and farther south and Shawnigan a considerable amount of logging with horse-drawn, heavy six-inch-tire trucks; the amount per load averaging 1500 feet.

In 1920 there was some hauling with hard-rubber-tired motor trucks. Prices for these logs ranged from $6 to $8 per M., in the former case towed to the Genoa Mill Co., with their own tug; in the latter with towage charges on the vendor.

W. HIGGINS

The first operator to use steam power throughout—except for horses to draw [the] main line back to the woods—was W. Higgins who was logging in quite a considerable way in 1897—and I believe sometime before this [at] Haslam Creek in Cedar District). (Note: Munday's two-drum yarder was extensively used on the Pacific Coast, Washington, as early as 1891 and therefore operators here appear to have lagged a little in adopting them.)

In 1899 he moved to Chemainus, and logged for the Chemainus Mill Co. (late E.J. Palmer, manager).

A few hundred yards north of Chemainus village the old Trunk Road swung to the west side of the railroad and continued so for several miles before recrossing the rails again to continue northward. On this old road about one and a-half miles north of Chemainus stood the original school-house, called the Horse Shoe Bay school; and some distance to the west of this, Higgins commenced operations, quartering his men in the above noted school-house.

From the locality of the school-house the terrain falls steadily to the sea-beach; and here a chute was built to carry the logs to the water. It was built of logs laid on the ground, and across the railroad, so that the logs shot over, just clearing the rails.

A flagman was stationed at this point when the logs were coming down; and, of course, there was an agreement with the railroad company respecting the time logs were to be sent down.

From my knowledge of the terrain with which I was familiar at the time, I would say the chute was half a mile long. It's length would compare favourably with the Klamathon chute, carrying logs into the Klamath River in Washington; but the latter was steeper, carrying logs at a great speed.

The Victoria Lumber & Manufacturing Co. sawmill at Chemainus. —Postcard courtesy of Chris Hill

LIKED BY HIS MEN

Higgins logged here for a year or more taking from this region a great amount of fine timber. His next move was to open up the belt of timber served by the Chemainus [Victoria Lumber & Manufacturing] sawmill] railroad, which continued into Camps 1, 2, 3, 4 and 6. Eventually he moved, I believe, to the mainland, and the company did its own logging.

Higgins was a logger of the “old school,” forthright and exacting; notwithstanding, he was liked by his men. Many is the tale I heard his old hands tell of him in after years.

At those times the logs had to be sniped on the end; and the sniping must be technically correct, and all knots must be trimmed clean. Higgins would be right around in the workings, watching everything; sometimes he would pick up a man's axe and examine it; he required good men and he got them.

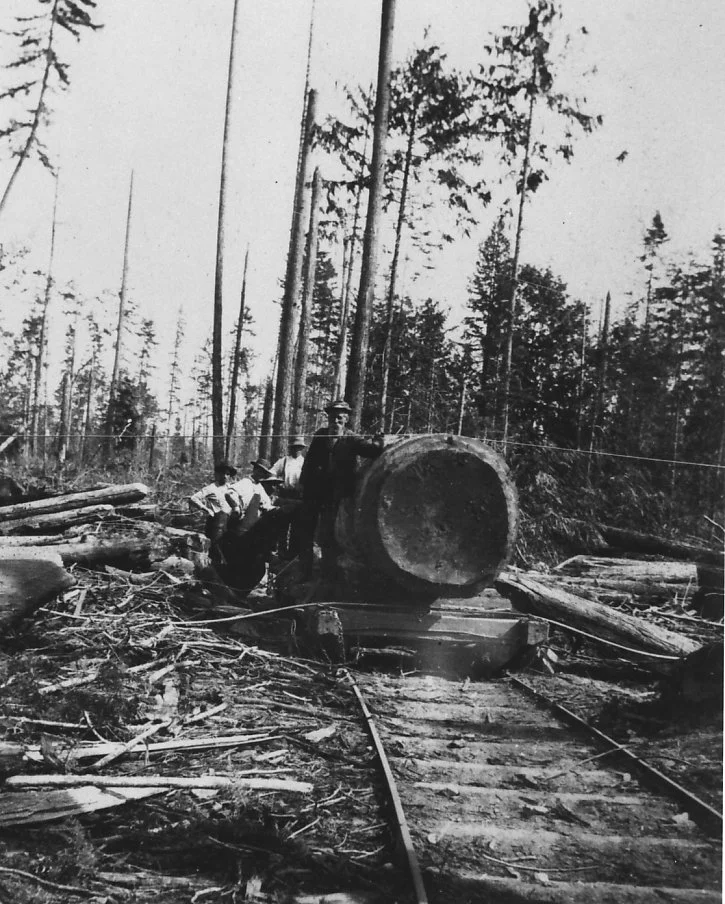

A perfect example of ‘sniping,’ the ends of the log having been cambered so it would slide easier over the rough ground before it was loaded onto a railway carriage as shown here.—Author’s Collection

In the summer of 1903, I was employed in Chemainus Camp No. 4. Tom Frost, foreman, and Bob Sprouler, hook tender under whom I worked (I was a chechako, were both old Higgins men.

The yarding donkeys drew the logs to a main skid-road and a powerful road donkey, with wide main line, receding and spool drums, drew them in long strings to the loading landing, where they were loaded on the cars by a par-buckling method with the spool drum.

This wider donkey was made in Victoria by the Albion Iron Works, and was called the Albion. Using one and a half-inch steel line—in logging parlance the steel cables are always called line: main, haul-back, sky-line, straw-line, etc.— the Albion could haul a great string of logs several thousand feet.

The logs were loaded on four-wheel trucks, the load of logs making the connection; the brakes were on the sides of the trucks, and the brakeman, as the engine slowed down on approaching a declining gradient, had to run between the trucks to set the brakes. The trucks were coupled together with chains when returning empty to the woods.

These hazard-inducing two-truck cars were in use in the Mayo camps as late as 1917, soon to be superseded by the skeleton car connected by 10 x 10 [inch] timber, strengthened by steel plates and equipped throughout with air-brakes.

DEATH BETWEEN RAILS

In 1902 or ‘03 the Chemainus Co. opened Camp 5 serviced by a railroad which passed underneath the E&N, a mile north of Ladysmith. Here the grades were very steep and a geared locomotive called the Climax was used for drawing logs in large long strings on planking which was laid down between the rails.

Accidents did not often happen in these times, but a shocking death occurred here in the winter of 1903. Frank Bourke, one of the hook-tenders, had been seen in Ladysmith (reminiscence of Mr. Pat Barry). It was remarked that he was “pretty drunk". He started for camp over the plank road. Bob Crowel, who had brought the Climax out from the factory, was the engineer.

The engine was returning to camp rear-ended since there was no ‘Y’ here for turning—where there was no turntable a ‘Y’ was used to turn an engine—and there were no lights on the rear end.

SHADOW ON TRACK

As he neared camp in the darkness of the winter evening, Bob Crowel thought he saw a shadow on the track. He brought the locomotive to a standstill, and with the fireman got down from the cab, but nothing was seen or heard; everything appeared normal.

In some perturbation, nevertheless, he continued on a short distance to the blacksmith shop, where the blacksmith and his assistant Mr. Barry were standing by. Crowel, as he climbed down from the cab, remarked that he had a feeling he had struck something a short distance down the track. Fireman Joe Vipond was on hand immediately.

They got lanterns; yes, there was a body ground up in the gears. The blacksmiths had worked all the previous night setting in a new steam brake beam—she was braked with steam—and now they must tear all this out to release poor Bourke's body. It was reverently released and laid on some boards.

ALL NIGHT VIGIL

There had been about a dozen huskies standing about; but, as Vipond quietly remarked, “We must set a couple of you fellows to stand watch through the night,” they mysteriously faded away, leaving only Pat and another man. They willingly assumed the sad vigil, for poor Bourke was well thought of. Some compassionate woman in the camp came with a sheet and covered the body.

In the summer of 1905 I was employed in this camp under foreman Harry McGarrigle—Vipond had opened a camp at Lake Cowichan—and the method of drawing the logs over the planks with the locomotive was soon to be abandoned, as the haul was becoming too long to be profitable.

In this year the ground system of logging was still practised; but workers coming from the American side were heard to say, “they were commencing to use the high-lead” system over in Washington.

* * * * *

Nathan Dougan hasn’t finished his tale of the early days of logging in the Cowichan Valley, of course, but that’s enough for today. There will be more vignettes from Cobble Hill’s home-grown historian and storyteller in future Chronicles.