Ned McGowan’s War

Part 1

As Wikipedia so blandly puts it, “McGowan's War was a bloodless war that took place in Yale, British Columbia in the fall of 1858...at the onset of the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush. It was called Ned McGowan's War after one of the conflict's main antagonists...”

Bloodless it may have been, a tempest in the proverbial teapot, a farce, even. But bland, never!

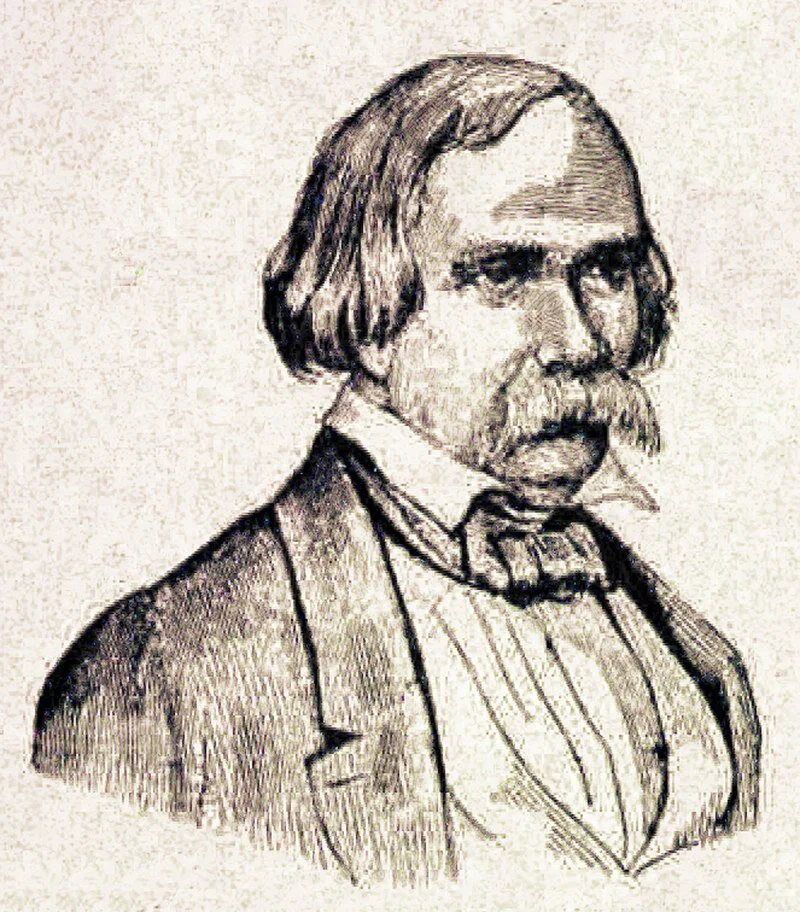

Hill’s Bar ‘antagonist’ and ‘belligerent,’ Ned McGowan could be a charming rogue—even some of his enemies couldn’t help liking him. -Wikipedia https://archive.org/stream/narrativeofedwar00mcgo#page/n14/mode/1up, Public Domain

To diss Ned McGowan as being just “one of the main antagonists” is an insult, not just to the man himself but to anyone who enjoys a good story. In reality, colonial administrators feared Ned McGowan, who’d barely escaped a hangman’s noose in California, as a direct threat to British sovereignty of mainland British Columbia.

In response, Governor of Vancouver Island James Douglas called out the army, in this case the Royal Engineers, under the command of Colonel Richard Moody. With ‘Hanging’ Judge Matthew Begbie, his orders were to put down the purported uprising of American interlopers at all costs.

Even with these historical heavyweights playing lead roles in the ensuing drama, it was disgraced ‘Judge’ Ned McGowan who stole the show.

* * * * *

A Fraser River gold nugget; they’re still being recovered after 160 years. x—https://howtofindgoldnuggets.com/

Inevitably, not all of those who were attracted to British Columbia by the lure of gold were sterling of character and welcome immigrants to this farthest-west of the Empire.

Hard on the heels of the miner and the merchant came the camp followers.

Gamblers, thieves, fallen women—and considerably worse—also headed for the riches of Fraser River. Unlike the prospectors, these fortune hunters had no intention of stooping to honest toil with pick, pan and shovel.

Rather, they hoped to mine the miners with all the temptations of human vice, from loaded dice to loaded gun.

Perhaps the most spectacular, although certainly not the worst, of this motley army was the ubiquitous Ned McGowan. His stay in British Columbia was brief—but his influence on the provincial course was memorable. Few of the thousands who flocked to Fraser River created so much excitement as this charming rogue from California who almost sparked a “war.”

Philadelphia-born of Irish parents, Ned began his tempestuous career as a typesetter with a printing firm. Young Edward proved himself to be fast, hard working and reliable—the very antithesis of the Ned McGowan of later years—and to all appearances was an honest and up-and-coming young man.

Philadelphia in the 1850s where Ned McGowan began his working career as a compositor, lawyer, politician, police officer—and bank robber. —Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia

His future as such seemed even more assured when, in 1835, he began to study law. But it was during this period that he also became involved in politics where he quickly displayed a natural ability as a speaker and behind-the-scenes manipulator for the Democratic Party.

Naturally flamboyant, charming and ambitious, he found the rough and tumble arena of politics far more satisfying and rewarding than either printing or law.

Senior Democrats were quick to see his potential and, in 1847, after serving three terms as District Clerk, Ned was nominated as the party’s candidate for a seat in the Pennsylvania legislature. Elected, he again demonstrated his flare for politics by acting as opposition spokesman.

To McGowan, politics was a war and, when giving a speech, he went for the Republican jugular. Time and again he viciously attacked the governor, until the editor of the State Gazette denounced his muck-raking in a strongly-worded editorial.

Ned, who’d proved himself a master at dishing it out, showed that he lacked the most essential aptitude of a politician—a thick skin.

He demonstrated this dramatically and violently the day after the editorial which had called him a bully, by stabbing the Gazette’s editor. Luckily for all concerned, the editor lived and McGowan, instead of going to jail for attempted murder, enjoyed the full support of the Democrats who were able to pull the necessary strings.

Ned, after resigning his seat, simply left town until the excitement subsided, later returning to Philadelphia as big as life to be made a captain of police!

It may seem an odd role for a would-be murderer but such was politics in the good old days. Ned, no longer hindered by having to keep up appearances as a legislator, now devoted himself to having a good time. But wine, women and song were costly pursuits, even for a corrupt police officer and, ere long, he was in need of money. His solution to the problem became a matter of public record when the erstwhile captain of police disappeared immediately after the robbery of a bank.

When found, he was disguised as a sheepherder and loaded down with the bank loot.

Arrested, he was arraigned for trial. There was no back-room finagling to save him this time and, upon being convicted, he had to escape and head West.

By then the great rush was on to California and Ned joined the human exodus to the gold fields. He found his own brand of El Dorado in San Francisco which was then in the iron grip of a corrupt regime. Upon exercising the political skills he’d honed in Philadelphia, Nick quickly rose to the top, being elected an Associate Justice of the Court of Sessions.

He then received a gubernatorial appointment to the post of Commissioner of Immigrants. Lest anyone back east question the commissioner’s integrity, Judge McGowan had the territorial legislature pass a special bill declaring his bank robbery conviction to be null and void.

Quite aware of what would happen to him if he fell into the hands of the vigilantes, Ned went underground.

Unable to leave the city, he hid in the room of a friend. For 10 days and nights he cowered in the small apartment, and peeked through the curtains at the vigilantes’ headquarters which were in full view of his hiding place.

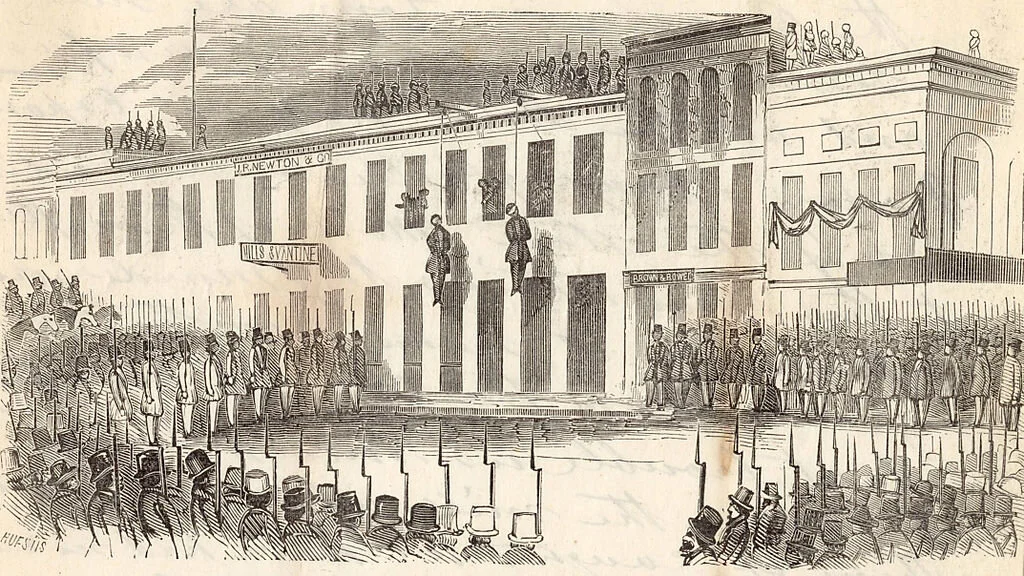

Daily, he saw friends and associates, including James Casey, escorted into the building for quick trial and dispatch. Those found guilty of more serious crimes were promptly dealt with at the end of a rope—a fate which did nothing to ease McGowan’s state of mind.

Charles Cora and James Casey hang from this makeshift gallows, 1856. —Wikipedia. By Huestis, Charles B. (active ca. 1856-ca. 1859), artist Town Talk, printer - http://content.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/tf229007rh/?layout=metadata, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=242284

Then, disguised as a priest, he made his way through the vigilantes who were scouring the city for him, and continued to Santa Barbara where, despite being betrayed by a friend, he slipped across the border into Mexico and waited for the vigilantes to lose interest in him.

Months later, he turned up in Sacramento. There, safe from justice in the Bay City, he made his headquarters at the Magnolia Saloon and entertained a large following of hangers-on with stories of his daring escape from certain hanging.

For that matter, Sacramento seemed like a second home to the judge, as many of his fellow refugees from justice had sought refuge there.

When asked by a Sacramento newspaper about his disappearing act, McGowan cheekily replied that he was afraid that he would be seized by “the Vigilance Committee’s sheriffs, and that these well-meaning but mistaken gentlemen would hang me as a felon before an honest man could be found who knew me and could prove my innocence”.

This was the “ubiquitous” Ned McGowan who was shortly to make his presence felt in British Columbia.

But before seeking his fortune in a foreign land, Ned exhausted every effort to whitewash his past. Through influential contacts in the California Legislature, he won a change of venue from San Francisco to the wide-open settlement of Napa City where, assured of acquittal by judge and jury bought and paid for, he willingly presented himself for trial in the murder of James King.

At this time, Napa was notorious as a haven for the criminal elements of the whole territory. It resembled, as the San Francisco Bulletin moaned, allegorically, of Sacramento during McGowan’s stay there, “one of the Jewish cities of refuge, where murder and other criminals could flee for shelter from the avengers of blood”.

The Bulletin, not unnaturally, was embittered by the murder of its editor and rightfully denounced Ned’s trial as a farce.

“Ned McGowan, the cunning but cowardly and unprincipled man who has played so conspicuous a part in the villainy that has heretofore been practised in this city, the tool and accomplice of equally as guilty parties now in our midst, has at last been caged in Napa, and is undergoing a farce of a trial, which is only intended to create sympathy for a hardened wretch, totally unfit to be loosed on society.

“Nearly three months since, this fugitive from justice made his appearance on the public street of Sacramento.

“Under the eye of the very governor who claims to have offered a reward for his apprehension, he was suffered, although under the indictment of a grand jury, to roam at large, hold levees, and be lionized by men of the same stripe. He was not only persuaded to ask for special legislation on his behalf, but members seemed eager to obtain his favor by granting his request, and he was permitted to occupy a seat within the bar of the assembly, during the sessions, by the side of a boon companion.”

Acquitted of any complicity in King’s slaying—the court ruled that King died as the result of the doctor’s treatment rather than Casey’s bullet—McGowan, who now revelled in the role of a public hero, was delighted by newspaper accounts of his escape from “persecution” in which he had been termed “ubiquitous”.

He returned to San Francisco to publish a newspaper under this name but the scandal sheet failed within months.

San Francisco had changed since the lawless days before the vigilantes and, although legally acquitted of the one and only criminal charge against him, Ned no longer fitted in. It was time to seek greener fields, greater challenges, greater fortunes—a decision made all the easier when a would-be assassin took a shot at him, the bullet passing through the lapel of his coat.

It was time to head for British Columbia.

When Sarah Crease made this sketch of Hill’s Bar in 1862, the excitement was over. The miners had moved on to new strikes, and the ‘ubiquitous’ Ned McGowan had returned to the United States where, it was once reported, he’d been killed by Apaches. —Wikipedia

The discovery of gold on ‘Fraser’s’ River had caught the future province ill-prepared for the onslaught of humanity which followed this latest rainbow. Among the vanguard was the illustrious Judge Ned McGowan (until his dying day, he continued to use this ‘honorary’ title). Upon making his way to Hill’s Bar, then the richest and busiest camp, he soon found himself a popular leader of the local mining community and the owner of one of the best-paying claims.

Nightly, he held court before the inevitable following of barflies and idlers.

Even without a rich claim, Hill’s Bar was the likely headquarters for someone like Ned McGowan. Situated just over a mile downstream from Fort Yale, Hill’s Bar had mushroomed into a shantytown in the months following the discovery of gold by James Moore and companions. It would, in fact, prove to be the richest of all Fraser River sandbars, yielding more than $2 million.

As it had attracted the first influx of miners, most of whom were American and little inclined to respect British authority, Hill’s Bar had also provided Vancouver Island Governor James Douglas with his first major challenge since the discovery of gold.

Faced with what amounted to an invasion of Americans, Douglas, who as Governor of the Colony of Vancouver Island and Chief Factor of the Hudson’s Bay Company, had no legal jurisdiction on the Mainland. He gambled that the Colonial Secretary would support him when informed of his actions, and issued a proclamation of authority over the gold fields.

To enforce his ultimatum, he appointed George Perrier as magistrate for Hill’s Bar and Henry Hickson as constable. For bustling Fort Yale he named Capt. P.B. Whannell justice of the peace, George Donnellan chief of police.

As envisioned by Douglas, both Perrier and Whannell had their own areas of authority. In cases where their jurisdictions overlapped, he expected them to cooperate with each other for the common good. He didn’t anticipate the spirit of rivalry which existed between the two camps, or the lengths to which their respective keepers of the peace would go.

Or that a California desperado named Ned McGowan would trigger alarm bells that the preponderantly American presence on Fraser River was a direct threat to British rule.

But he would soon find out.

(To be continued)

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.