Pacific Coast Colliery - Doomed Miners' Day in Court (Conclusion)

(With thanks to South Wellington’s resident historian Helen Tilley for sharing her extensive files and the Ladysmith & District Historical Society’s Rick Morgan.)

Human error. It has always been with us, always will be.

For the 19 miners of the Pacific Coast Coal Mine on the morning of Feb. 9, 1915, someone’s carelessness cost them their lives.

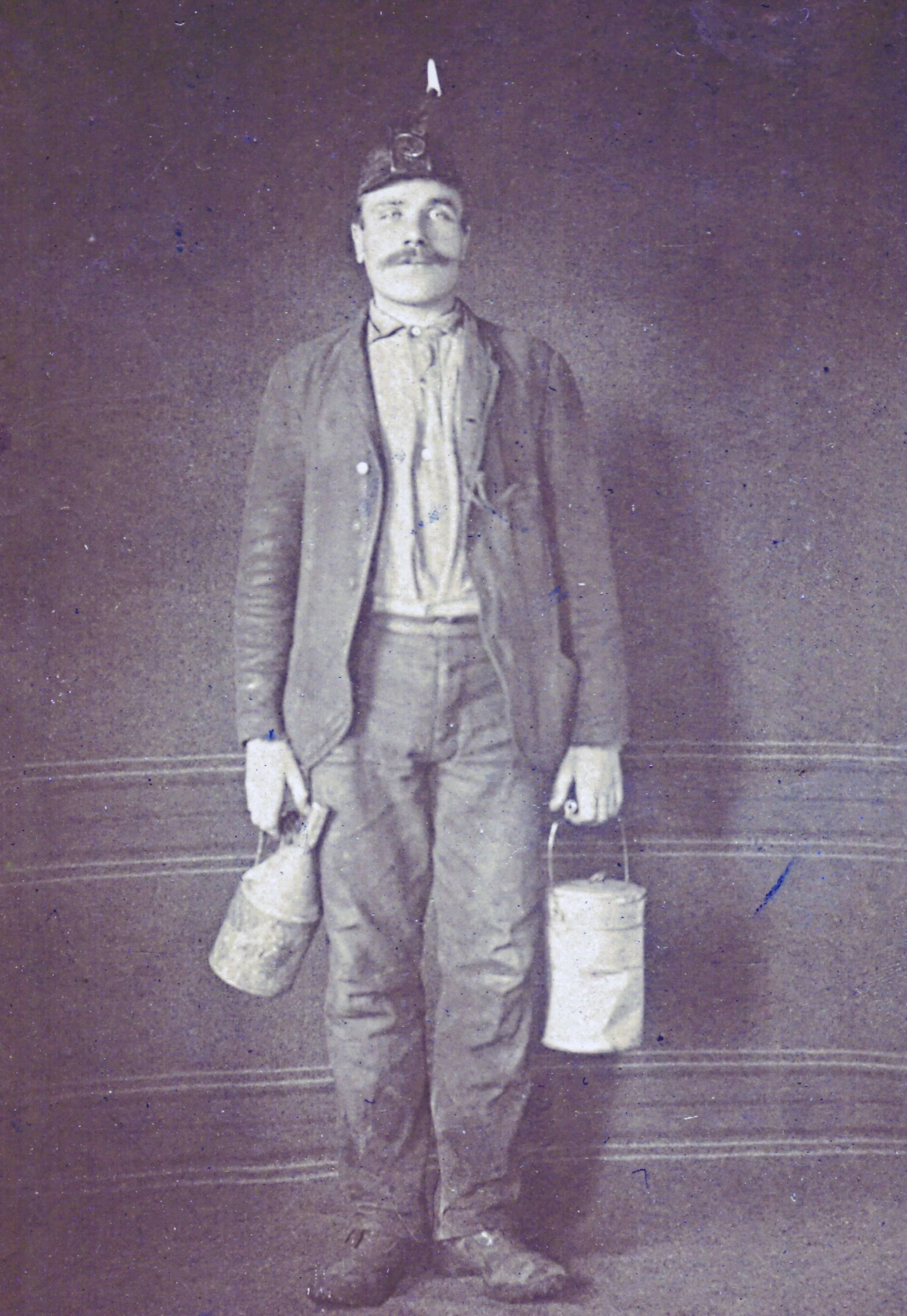

A typical coal miner of the period; sadly, we’ll never know his name. Note his lunch bucket and powder can (left).—Courtesy Tom Teer

As we’ve seen, someone misfiled the plans showing the conversion of scales between the abandoned and flooded workings of the adjacent Southfield Mine, and the working PCC Mine.

The plans that clearly showed that the miners weren’t 440 feet from danger as they believed, but within just a few feet of disaster.

Clearly, someone was responsible for an oversight that bordered on criminal negligence. But if not PCC Mine manager Joseph Foy, who was one of the victims, who?

The B.C. Attorney-General’s office was so sure where the fault lay that it pressed criminal charges against two of the principles involved in the tragedy. That one of them was the PCCM’s Managing Director John H. Tonkin probably came as no big surprise to many.

But the Chief Inspector of Mines, Thomas Graham?

* * * * *

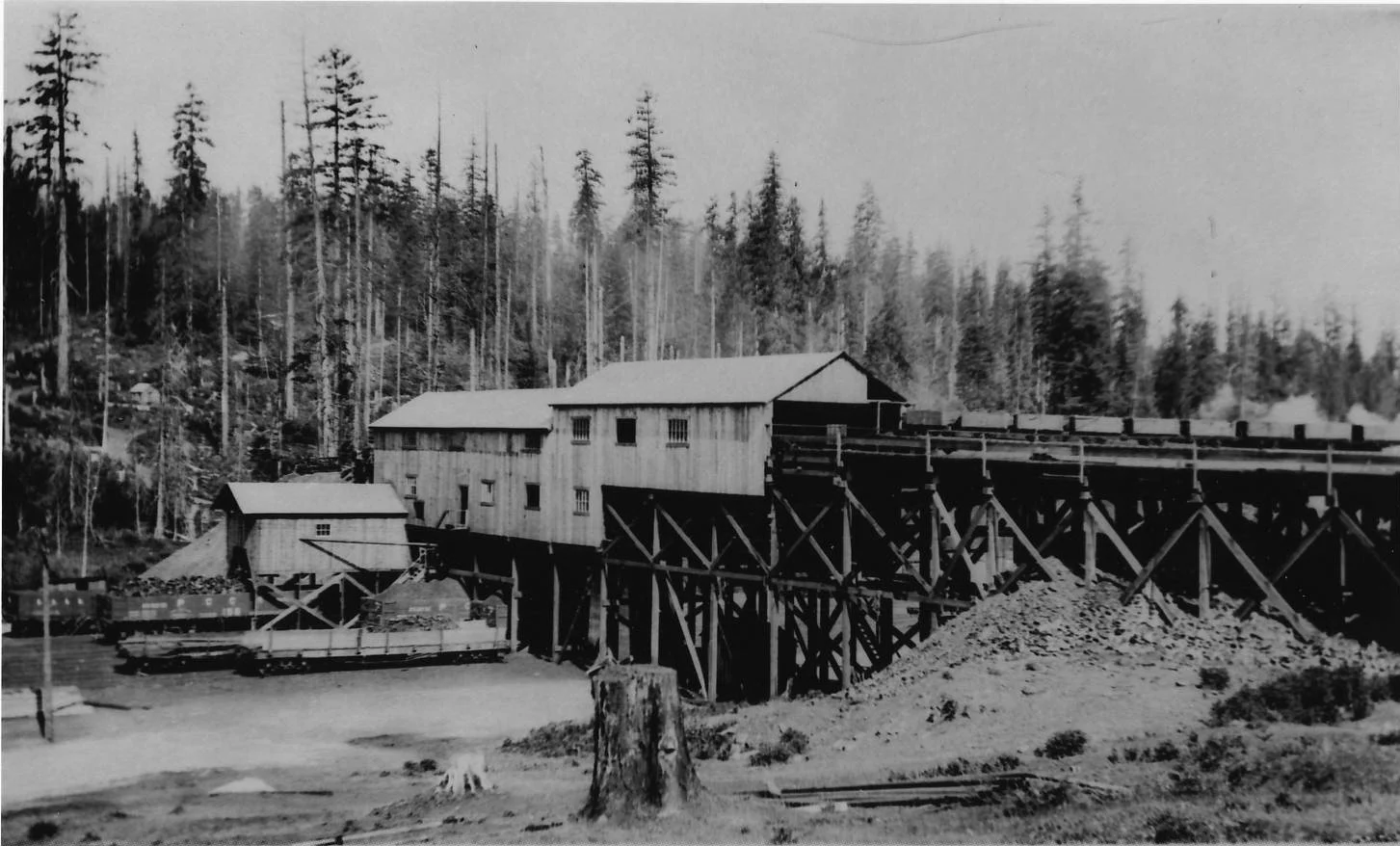

The Pacific Coast Coal Mine, South Wellington. —Courtesy Helen Tilley

There’s a story in itself of how the South Wellington Colliery had had to fight coal baron James Dunsmuir’s lawyers all the way to the highest arbiter in the British Commonwealth, the Privy Council, for the right to mine the coal. But not today. Suffice to say, what coal there was left untouched between the Southfield to the immediate north, and the also abandoned and flooded Alexandra to the south, had to be mined with due care and attention.

Which was entirely practicable given the highly accurate underground surveying available at the time. Hence Manager Joseph Foy’s absolute confidence that a safe buffer existed between his mine and the Southfield.

Until that mid-morning in 1919 when fireboss David Nellist detonated the fatal shot that broke through into the Southfield and the resulting rush of water drowned 19 men, Foy included.

As explained last week, the old Southfield Mine had used the British measurement of 132 feet to the inch, but since 1911 provincial mines, including the PCCM, had used the American scale of 100 feet to the inch. This meant a difference of no less than 752 feet between the plans of the two mines.

The PCCM disaster occurred because the plan overlay differentiating between the two scales had somehow been filed away in a drawer in the office—the PCCM was working with the wrong scale.

We’ve also seen a partial explanation of how that likely occurred. How, since 1908, the PCCM had experienced multiple changes of most of its original executives and key personnel, among them the draftsman who’d drawn the plans delineating both scales. By 1919, latecomer Joseph Foy was serving as both company superintendent and mine manager and was, quite likely, overworked.

Surely, he had to have been unaware of the discrepancy or he wouldn’t have risked his own life besides those of his men?

There are anecdotal reports of the weeks leading up to the flood, of miners becoming ill from stagnant swamp water seeping into the mine from the Southfield. But Foy had satisfied Mines Inspector John Newton that this water was coming in from a swamp on their property not the Southfield workings and posed no danger.

* * * * *

Upon being informed of the disaster, Insp. Newtom leapt to the surmise that, 25 years before, the Southfield miners had exceeded the area shown on their plans, thus approaching nearer to the PCC property than was believed. As the old workings were flooded there was no way of confirming either way.

But Newman’s immediate superior in the Department of Mines, Chief Inspector Thomas Graham knew better.

Before joining the government he’d been superintendent of Western Fuels, the current owners of the Southfield property, and had personally authorized a set of the underground workings be given to the PCCM’s then manager George Wilkinson in 1908.

Until the bodies were recovered, however, a process that would take months, Graham thought it best, so he said later, to sit on this fact. Not even at the coroner’s inquest did he reveal what he knew—and it’s because of this reticence that he soon found himself in the legal hot seat.

* * * * *

So far, PCC Superintendent John Tonkin’s known role in the tragedy was his having, three months previously, asked Chief Inspector Graham to clarify the province’s barrier-pillar law. He was motivated by the fact that the PCC was running out of coal, had, in fact, already begun a new shaft at nearby Morden. Tonkin intended to extract all he could from the area of the PCCM alongside and beneath the Southfield.

Graham informed him that the Coal-mines Regulation Act required nothing more than a safe buffer and Tonkin promised to leave 250 feet between the old and new workings. He obviously changed his mind later as Manager Foy clearly stated to Inspector Newton, just six days before the disaster, that he intended to go to within 50 feet of the Southfield.

There was no avoiding an investigation and 10 days after the flood, Premier Sir Richard McBride announced there would be a public inquiry once the bodies were recovered. Because of the major pumping involved, this grim process couldn’t begin until May and an inquest was slated to begin in Nanaimo on the 17th.

B.C. Premier Sir Richard McBride who’d once served as Minister of Mines, ordered an investigation. —www.templelodge33.ca

Although by now sure that the use of the wrong set of plans had caused the tragedy, Chief Inspector Graham continued to keep his cards under the table, telling only the Minister of Mines what he believed. He said nothing at the inquest of his suspicions, only that he was awaiting the outcome of a new survey of both mines by a competent third party. What he meant was, a fresh study of the Southfield blueprints and an actual examination of the PCC once it could be accessed.

He promised to reveal all at the public inquiry.

Based upon the limited information at hand, the coroner’s jury, as reported in the Nanaimo Free Press, ruled: “We your jury return a verdict that Thomas Watson, Robert Millar and seventeen others met their death by drowning through the flooding of South Wellington mine on the 9th day of February, 1916.

“We are unable to place the blame at present on any party or parties but would strongly recommend that the Provincial government take immediate steps to have a re-survey taken and hold a rigid examination and if possible ascertain who is responsible for the lamentable catastrophe and place the blame on the right parties.”

Ah, yes, the right parties...

Once D.B. Morkill, BCLS, had confirmed that the PCCM had been using the wrong scale, and four months since the disaster, Commissioner Justice Murphy began the three-day-long inquiry in Nanaimo. He was tasked with examining the plans and workings of the mine, the conditions prevailing immediately prior to the flooding and, if possible, identifying both the cause and those responsible.

PCCM Managing Director John Tonkin took the stand the first day but come Graham’s turn, according to historian Rick Morgan’s account of the tragedy for the Ladysmith & District Historical Society, the chief mines inspector was “subjected to a severe cross-examination...for suppressing evidence at the inquest in allowing plans to be presented which he knew to be wrong”.

The result of the inquiry filled 48 pages with Justice Murphy damning Graham’s role: “The responsibility for the South Wellington disaster on Mr. Graham’s part is, however, purely negative. He is to blame, not for what he did, but for what he did not do, and what his official position made it his duty to do.”

His judgment of the PCCM’s Tonkin was even harsher, accusing him of having “played the active role.”

(I’m tempted to break Murphy’s judgment into shorter sentences for ease of reading, but offer them verbatim, sorry.—Ed.)

“With the full knowledge that Mr. Graham was leaving everything to him, that he, Mr. Tonkin, proposed to remove the 100 foot barrier wall right up to the boundary and then turn and run west directly towards the supposed location of the old Southfield workings again, to his knowledge long abandoned and partly filled with water, and with the further knowledge that he must have had as manager that water was freely flowing into the South Wellington No. 3 north level 300 feet down from the face, which water might be from a surface swamp and might be – as turned out to be fact – from the old Southfield workings, fully aware in addition that error meant death in all probability to many miners, what did he do?

“He proceeded to South Wellington to inspect the data and come to a decision (he did not reside at the mine, but usually visited it once a week). He was aware that at Nanaimo, 4 1/2 miles distant the original map of the Southfield workings was open to inspection in the office of the Western Fuel Company. Instead of obtaining it...he used copies, and copies which, on their face, considering the problem being decided, ought to have aroused suspicion.

“On him, in my opinion, rests the direct primary responsibility for the accident.”

There was no ignoring or sweeping away such a damning ruling and Attorney General W.J. Bowser proceeded with manslaughter charges against Graham and Tonkin. At the preliminary hearings, held separately late in September, counsel for both men argued strenuously for dismissal of the charges, that the evidence didn’t warrant them.

Stipendiary Magistrate Kirkup disagreed and ruled that the evidence justified both men standing trial in a higher court.

The law moved much faster in those days and, on October 27, just over seven months after the disaster, a grand jury exonerated Tonkin and Graham. Their verdict didn’t go down well with presiding judge Mr. Justice Clement who, reminiscent of the late ‘Hanging’ Judge M.B. Begbie’s tirades against recalcitrant juries, termed them “the most irresponsible body known in law”.

* * * * *

John Tonkin returned to Salt Lake City, Utah and, just over two years after the PCCM tragedy, Thomas Graham resigned as Chief Inspector of Mines. Ironically, his replacement also had deep ties to the ill-fated PCCM, George Wilkinson having been its manager in 1908. It had been Wilkinson who asked for and received the plans of the Southfield which showed that the scale was in chains, or 132 feet to the inch, not 100 feet to the inch.

The Department of Mines had drawn its own conclusion to the affair. Noting that “the information contained in the mine office, in tracings and blue-prints, worked to the proper scale...show[ed] the correct relative position of the workings of both mines,” Mines Inspector Newton asked how the information had “escaped the notice of the colliery staff...”

He wrote that he couldn’t have foreseen that “the information so contained in the office would be so overlooked or misapplied”. After declaring that “mere legislation” couldn’t prevent such accidents, he suggested that the Coal-mines Regulation Act, which allowed owners of closed mines to withhold access to their company files, be amended to read: “Any owner or lessee operating a mine or property adjoining [an] abandoned mine, and the Inspector in charge of the district in which the abandoned mine is situated, shall, on application to the Minister, be furnished with a copy of the abandoned mine so deposited.”

How sad that the owners of the PCC Mine had, in fact, been provided the plans, only to file them away in a drawer. For this oversight, 19 men paid with their lives.

* * * * *

The restored tipple/headframe at Morden Colliery Provincial Heritage Park is one of the few real reminders of what once was the Island’s greatest industry. Few visitors have so much as a clue to the tragedy that struck this mine’s predecessor, two miles distant.

With Morden Colliery, now a provincial heritage park, about to come on-stream, work resumed at the PCC on a reduced scale. But it was all too late by then, the company’s new and extremely expensive Morden operation failing in 1922.

Upon closure of the PCCM, some residents of the small town site remained and, during the Dirty ‘30s, unemployed miners reopened some of the shafts from the surface to extract remaining coal pillars. If you visit the site, just north of the village of South Wellington, you can still see rutted vestiges of their handiwork and of this historic mine but there’s not so much as a nail to show for the large boarding house which is prominent in old photos.

The PCC Mine’s most visible remnant.—Courtesy Helen Tilley

A cow pasture on the west side of the E&N Railway tracks was the site of the colliery buildings: the tipple, boilers, machine and carpentry shops, the rescue station and, just off in the trees, the manager’s house. A concrete blockhouse-type structure in the field, some concrete foundations in the trees that were the powerhouse, and mounds of coal waste are clearly visible to the many hikers who utilize the public trail that now cuts right through both mine and town site.

How many of them even notice or give thought to what they do see is anyone’s guess.

A sign warns of danger of gas and unstable ground at the site of the fan shaft, and all about are the signs of treasure hunters’ scratching.

I’ll close with the names of the men who, on the morning of Feb. 9, 1915, went down into the deep of the PCC Mine for the last time: Olaf Lingeran, Glaggoris Marvos, Robert Miller, Jim Hornis, William Gilson, William Irving, John Stewart, Peter Fearon, Joseph Fearon, Thomas Watson, Samuel Wardle, John Hunter, Frank Hunter, William Anderson, Joseph Cadr, Frank Marvelle, David Nellis, Joseph Foy, P. Finn.

Sam Wardle, one of the miners drowned when they broke into the abandoned Southfield Mine. —Courtesy Helen Tilley