Pacific Coast Colliery - Doomed Miners' Day in Court (Part 1)

(With warmest thanks to South Wellington historian Helen Tilley who graciously dug into her extensive archives at short notice.)

This year’s Extension Miners Memorial service, Ladysmith’s annual tribute to the 32 miners who lost their lives in a tragic explosion on Oct. 5, 1909, was held last week in front of the Metal Collage on the corner of First Avenue and Gatacre Street.

There’s little to be seen today of the PCCM colliery. —Courtesy Helen Tilley

To my knowledge, there never has been a latter-day memorial service for the lost men of the Pacific Coast Coal Mines colliery operation at South Wellington.

Today, it’s a farmer’s field, the right-of-way for a gas line, and third-growth trees bisected by the E&N mainline. Other than a concrete tower-like structure in the middle of a pasture, some concrete foundations of the powerhouse in the trees, and evidences of scattered and mounded coal waste, the once famous—perhaps infamous--PCC Mine has all but vanished.

Little, besides a sign warning hikers of “possible toxic gas and collapse,” to even suggest that this was a busy coal mine. Nothing at all to suggest that here is where, 107 years ago and 100s of feet below the surface, 19 men were drowned.

Today, a popular hiking trail goes right through the old PCCM town site which is honeycombed with sinks from the original workings and from the coal recovery efforts of unemployed miners during the Dirty ‘30s. This sign is posted beside a large, fenced-in depression from which you can smell rotten eggs—gas escaping from the fan shaft.

The deaths of the morning shift of the PCC Mine should never have happened, were in fact totally preventable. The single redeeming feature, such as it was, of this tragedy was that their deaths prompted, for one of the very few times in the Island coal industry’s history, some of the principles standing trial for criminal negligence.

* * * * *

February 1915: The Belgians were holding ground, fighting on the Eastern front was heating up, and Romania watched with growing alarm the massing of Austro-Hungarian troops on its frontiers.

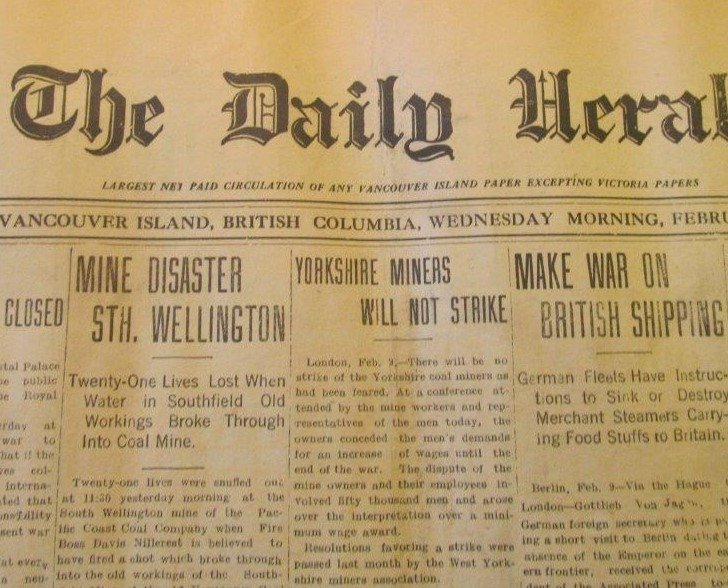

Much closer to home, in South Wellington, there was more tragedy, yet another disaster in Vancouver Island’s coal mining industry.

First reports, beginning on the morning of the 9th, were sketchy and terrifying: 24 miners of the Pacific Coast Coal Mine were reported to be in “imminent peril of their lives through an inrush of water” into the workings between the village of South Wellington and Chase River.

By the time the Victoria Daily Times went to press that afternoon (the Daily Colonist was Victoria’s morning newspaper), the situation, so far as was known, remained unchanged from that of the morning when miners detonated a charge and broke into the abandoned and flooded shafts of the old, adjacent Southfield Mine.

By afternoon, all attempts at rescue had failed.

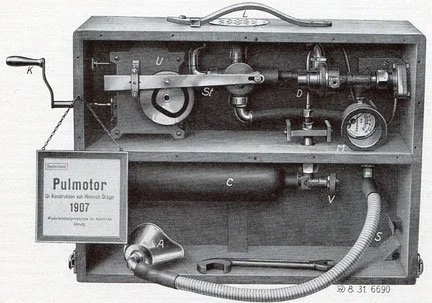

--grubenwehr-grubenrettungween.jimdofree

First word of the disaster had drawn 100s of miners from all the other workings in the district, as well as most doctors within immediate reach, in the event that any of the trapped miners were brought to the surface. In preparations for this eventuality, every pulmotor “for miles around was commandeered in case resuscitation was found to be necessary”.

“Little is yet known as to the exact extent of the disaster,” reported the Times, “but it is believed that the men are imprisoned in the workings of the Fiddick mine in No. 3 Slope. The water is said to have broken through from the old [Southfield] mine, which has not been worked for 25 years, and which adjoins the property of the Pacific Coast Colliery Company.

“Great suspense prevails in South Wellington and large crowds of people are gathering at the mine waiting for some news from the rescue parties as to the fate of the imprisoned miners...”

For the beleaguered community of South Wellington the grim drama unfolding deep underground was the second tragedy to strike within a year, the previous having been a fire that consumed much of the village.

—Courtesy Helen Tilley

Pacific Coast Collieries, owners of the Fiddick, or South Wellington Colliery, had assumed control of the shaft three years before and had recently opened its 610-foot shaft at nearby Morden. Located on the famed Douglas coal sea, the former Fiddick Mine was operated through two slopes. Due to the rolling irregularities of the coal seam, operation was conducted on the pillar and stall method, the ore being extracted by collapsing the temporary roof supports and hauled to the surface by horse-drawn carts and electrically-winched ore cars.

Well-timbered and ventilated, the PCM was a good producer, having yielded 200,000 long tons of coal in 1911 alone, but was slated for eventual closure in favour of the new Morden operation.

By the following morning, when it was the Colonist’s turn to publish, it was believed that 21 men were dead.

At 11:30 a.m. the previous day, it was reported, fire boss David Nellish [Nellist according to the Department of Mines Annual Report] had “fired a shot which broke through into the old workings of the Southfield mine of the old Vancouver Coal Company’s mine abandoned some 20 years ago. The old workings were filled with water, and when the shot broke through, the inrushng waters drowned all the men in the section of the mine affected...”

Only one man, W. Murdoch, was initially reported to have reached safety after a terrifying struggle in the darkness. Among the dead were Joseph Foy, mine manager, and fire boss Nellish who detonated the fatal charge. Ironically, Foy, who’d been on the surface minutes before the break-through, “upon hearing of the old workings being tapped,” rushed below to order the men out.

Helen Tilley: “Here is a photo from Joan Mayo titled: Sinking the Morden Shaft. Hero mine manager Joseph Foy is in the Bowler Hat. This photo was taken in 1912, three years before he died in the flood.” (Joan Mayo of Paldi’s famous Mayo Singh family was born in South Wellington.)

When he opened a trap door to the old stope, a wall of water smashed him against the timbers. Foy’s body was not among those immediately recovered.

Foy was 48, with a wife and eight children. David Nellish, 53, had remarried but a week before. Most of the other miners were single, the youngest 19-year-old Frank Hunter. Also among the dead was John Hunter, his father.

At least two heroes of the disaster were Thomas Watson of Chase River, and William Anderson, 22, who were working with the first shift when tragedy struck. Both men had reached a place of safety but chose to go back in search of their comrades.

Both men died for their efforts.

Although those on top, including the anxious relatives and friends of the drowned miners, had initially hoped that they were merely trapped, it had soon become apparent to many that the men died immediately upon the water pouring into No. 3 Slope.

Then had begun the unhappy task of recovering the bodies, a duty that mine inspector John Newton estimated would take at least two months due to the amount of water in the old Southfield workings, and the general swampy condition of the surrounding landscape. (The swamp is still there; trying to drain the PCC and its source, the flooded Southfield, would have been like trying to pump a lake dry.—Ed.)

Mourned the Colonist in an editorial: “The disaster at South Wellington, involving the loss of 20 lives was attended with circumstances of a particularly disturbing character. The doomed men evidently never had a fighting chance, and we can only hope that the death from which there could be no escape came to them with merciful swiftness.

“Coal mining is the most dangerous of callings, which those more comfortably situated ought to bear in mind when considering the labour disturbances which occur so often in regions where this industry is carried on.

“No matter how exhausting may be the regulations or how vigilant the inspections, there always is the possibility of explosion, or fire, as the sombre record of coal-mining fatalities unhappily demonstrates.”

The newspaper then asked the question that many were asking, and noted that, unlike most mine fatalities, in this instance “destruction came from an unexpected source [and] a searching investigation should disclose whether sufficient attention had been directed to the proximity of the workings filled with water.

“It must have been known that the old mine had become something of a reservoir.

“The location of its tunnels and chambers also was known. Was any heed given to these circumstances in the plan of operations in the adjoining property? These are matters that no doubt will be inquired into. Meanwhile what relief is needed should be given to those dependent upon the victims of the catastrophe, so suddenly plunged in sorrow.”

* * * * *

Half a world away on the Russian front, the world witnessed disaster of epic proportions.

But, for many Vancouver Islanders, grim and stark tragedy was homegrown reality. Ensuing news account of the PCCM disaster became something of a diary of horror as full details of the events leading up to, and immediately following, became known.

Fortunately, the death toll hadn’t gone higher as 100 miners had been at work in No. 1 Mine when water broke through into No. 3 north level, drowning 20 and sending 80 miners fleeing for their lives. Four and a-half hours after, rescuers were driven back by a second flood that effectively ended all immediate attempts to recover bodies.

For the first time, it was revealed that, four months before, water had burst into No. 4 west level without doing any damage. The subsequent disaster in No. 3 north was the first fatal flooding in Island coal mining history.

As Nanaimo coroner Thompson scheduled an inquest, Pacific Coast Collieries announced special compensation for the families of victims amounting to $1500 ($71 each if divided equally among the estates of the 19 lost men).

A Victoria newspaper reporter on the scene described the community of South Wellington as being in a state of shock. Hundreds of feet below the surface where, but hours before, 80 men had fled before a tidal wave of dirty water, coal dust and dislodged timbers, 20 of them dying almost instantly, much of the No. 1 Mine lay flooded and abandoned.

After the second break-through of water from the old Southfield workings, all attempts at rescue and recovery of bodies were suspended indefinitely.

Hindering government investigators was the fact that manager Foy was among those killed, making preliminary attempts to pinpoint the cause of the accident difficult. Although the ill-fated mine operation had been skirting the abandoned Southfield workings, according to PCCM calculations, 450 feet of coal separated No. 3 from the flooded workings, a barrier of 50 feet being considered a safe margin.

In Nanaimo, company president John H. Tonkin gave a prepared statement to the press, defending his firm’s method of operation. “I deeply regret the heavy loss of life which attended this disaster, and cannot account for the Southfield workings. The maps show that we were not within 200...feet of registered workings of the old mine.

“Every precaution had been taken to allow plenty of barrier space between the two workings and where the Southfield mine had been worked to the boundary, we had left a solid wall of 170 feet of coal, to prevent exactly what happened yesterday.”

Speaking for the United Mine Workers’ Association, president Robert Foster called for a thorough investigation by the provincial government. Said Foster: “I feel sure that there has been some terrible mistake made in either the measurements of the workings, or also the usual boring for safety has not been carried out.

“I have been talking to several of the miners who worked in the No. 3 level, and they state that the conditions were not altogether of the best of late weeks.

“Men have emerged from the mine with vomiting fits caused by the stagnant water which they were approaching. As to the result of an investigation, I cannot state what steps the UMWA will take. If the men complain of the conditions in the mines they are invariably discharged, so that it is hard for us to secure someone to appear [before] the mine inspectors.”

For the company, the disaster meant a complete halt to its operations at South Wellington for an indefinite period. For the townspeople, it meant an agony of waiting for recovery of the bodies and grief.

“No one can tell of the misery that this disaster brings to South Wellington,” wrote a reporter, “but with the usual fortitude of the mining element, the survivors are bearing their loss with magnificent courage.

“There was no panic in that little village when the dread message was sent out that the mine was flooded. The excited gathering of the relatives of the entombed men aroused the sympathies of those who were fortunate enough to have escaped, and fathers, mothers, sisters and sweethearts united and watched longingly at the dingy little mouth of No. 1 mine, but as the rescuers disappeared into the very bowels of the earth and came back without any sign of the doomed miners, tears came to the eyes of the watchers and they melted away to resume their sorrowful wait in the solitude of cosy homes that had housed happy families but a few hours before...”

Samuel Wardle, great grandfather of popular musician David Gogo was one of the miners lost in the flooding of the PCCM. David’s musical tribute to the lost PCCM miners won him a Juno nomination.—Courtesy Helen Tilley

Although there had been no shortage of volunteers for a rescue operation, it had been obvious to many from the start that those still below were dead. Initial rescue attempts had been foiled early by the rising water although some expressed the faint hope that, just possibly, some of the trapped men had been able to make their way to a dry ledge where they’d be able to hold out for days.

As slight as this hope had been, it had to be abandoned that afternoon when the second break-through of flood water occurred.

Throughout those agonizing hours, small groups of mothers and children huddled together in silence at the mine entrance. Smaller children, unaware of the tragedy unfolding about them, amused themselves beneath a bright February sun. Occasionally, a woman would burst into tears then struggle to regain her composure. Finally, with the realization that all were, in fact, lost, the small groups began to turn slowly homeward...

(To be continued)

* * * * *