Pacific Coast Colliery - Doomed Miners' Day in Court (Part 2)

(With warmest thanks to South Wellington historian Helen Tilley who graciously dug into her extensive archives at short notice.)

Of all the coal mining disasters in Vancouver Island’s history that of the PCCM in South Wellington stands out on two counts.

First, that it was caused not by the usual suspects, gas, explosion or cave-in, but by flooding. Second, that, for once in an industry that all but accepted dangerous workings conditions and their consequences as the cost of doing business, criminal charges were laid.

Someone had screwed up.

19 men had died.

Someone had to pay.

* * * * *

There’s little to be seen today of the PCCM colliery. —Courtesy Helen Tilley

Today, it’s a farmer’s field, the right-of-way for a gas line, and third-growth trees bisected by the E&N mainline. Other than a concrete tower-like structure in the middle of a cow pasture, some concrete foundations of the powerhouse in the trees, and evidences of scattered and mounded coal waste, the once famous—perhaps infamous—PCC Mine has all but vanished.

A popular hiking trail now runs within feet of where the mine entrance was situated and through the mini-town site on the east side of the railway tracks. Little, besides a sign warning hikers of “possible toxic gas and collapse,” to even suggest that this was a busy coal mine.

Nothing at all to suggest that here is where, 107 years ago and 100s of feet below the surface, 19 men were drowned.

Today, a popular hiking trail goes right through the old PCCM town site which is honeycombed with sinks from the original workings and from the coal recovery efforts of unemployed miners during the Dirty ‘30s. This sign is posted beside a large, fenced-in depression from which you can smell ‘rotten eggs’—gas escaping from the fan shaft.

The deaths of the morning shift of the PCC Mine should never have happened, were in fact totally preventable. The single redeeming feature, such as it was, of this tragedy was that their deaths prompted, for one of the very few times in the Island coal industry’s history, some of the principles involved standing trial for criminal negligence.

* * * * *

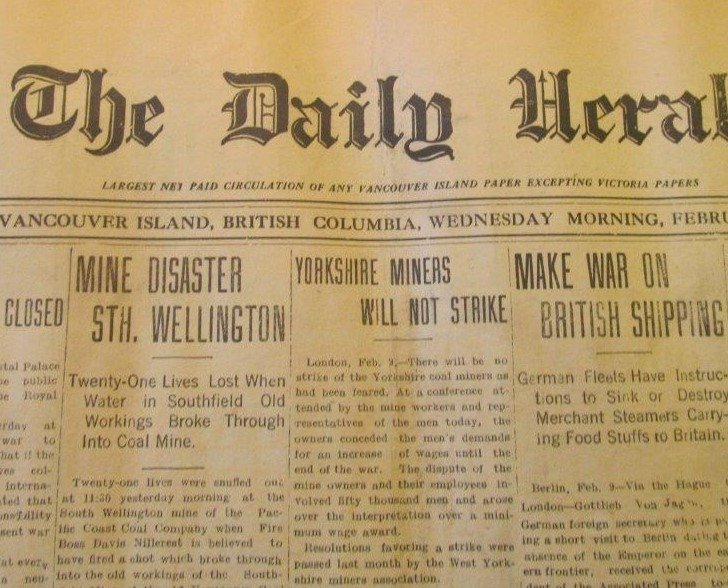

First reports, beginning on the morning of Feb. 9, 1915 were sketchy and terrifying: 24 miners of the Pacific Coast Coal Mine were reported to be in “imminent peril of their lives through an inrush of water” from the adjacent workings of the New Vancouver Coal Mine Company’s abandoned and flooded Southfield Mine, between the village of South Wellington and Chase River.

By afternoon, despite the efforts of 100s of miners from the other collieries in the district, all attempts at rescue had failed.

For the beleaguered community of South Wellington the grim drama unfolding deep underground was the second tragedy to strike within a year, the previous having been a fire that consumed much of the village.

—Courtesy Helen Tilley

Pacific Coast Collieries, owners of the Fiddick, or South Wellington

Colliery, had assumed control of the shaft three years before. Located on the famed Douglas coal sea, the former Fiddick Mine was operated through two slopes. Due to the rolling irregularities of the coal seam, the operation was conducted on the pillar and stall method, the ore being extracted by collapsing the temporary roof supports and hauled to the surface by horse-drawn carts and electrically-winched ore cars.

Well-timbered and ventilated, the PCM was a good producer, having yielded 200,000 long tons of coal in 1911 alone, but was slated for eventual closure in favour of the new Morden operation.

Today the restored Pacific Coast Coal Mining Company’s concrete headframe/tipple at Morden is a provincial heritage park.

Disaster struck at 11:30 a.m., February 9th, when fire boss David Nellist fired a shot that broke through into the Southfield and “the inrushing waters drowned all the men in the section of the mine affected...”

Only one man, W. Murdoch, was initially reported to have reached safety after a terrifying struggle in the darkness. Among the dead were Joseph Foy, mine manager, and fire boss Nellist who detonated the fatal charge. Ironically, Foy, who’d been on the surface minutes before the break-through, “upon hearing of the old workings being tapped,” rushed below to order the men out.

For the miners who survived there was grief for lost comrades, relief in their own escape, and pride in the way some of their fellows had answered the call.

Young William Anderson had reached the upper level and safety when he’d remembered his brother-in-law Robert Miller. Without a moment’s thought for himself, Anderson headed back into the mine and rising waters, to be seen no more. Earlier, “the plucky little Scotsman” had saved the lives of Casey Jones and John Murdock when he’d warned them of the flood below.

Tom Watson, it was learned, had died in the act of helping Manager Foy pass the alarm to those working below him, having been engulfed in a sudden rush of water and debris. Of those who were at work in No. 3 north level when fire boss Nellist fired the fatal shot, only three—John Murdock, Milford Devlin and Fred Gregory—escaped.

—Courtesy Helen Tilley

Working farther back from the head of the tunnel, they were carried to safety by the flood which swept them into higher levels. The same tide carried the heavy ore carts before it “as if they were so many matchboxes”.

Murdock, apparently, had been the last living man to speak with Manager Foy and had distinctly heard the screams of his drowning comrades, having had to wade the final 100 feet in water up to his waist. Devlin had heard the dull boom of the explosion and, not liking the sound of the rumbling that followed, fled for the surface without so much as getting his feet wet.

Ironically, the heroic Thomas Watson had begun work in the mine that very day. The ill-fated Fearon brothers were relatives of Manager Foy and had worked in the mine for only two weeks. New Zealander Ollie Legrion had arrived in South Wellington that Sunday, his second day in the No. 1 his last.

Company president Tonkin, in Victoria when notified of the disaster, rushed to South Wellington by car to oversee pumping operations. Six were immediately put to work, two more powerful electric pumps being ordered from Vancouver.

Interviewed by a reporter, provincial mine inspector Newton explained that he’d inspected both No. 1 and No. 3 mines just a week before and found everything “in the best of condition”.

In fact, he’d commented favourably upon the complete absence of that miner’s nemesis, gas. He said that he’d not detected a sign of seepage in No. 3 level or any indication whatever of the impending disaster. He acknowledged, however, a “slight flood” in No. 4 west level some months before, which also had been caused by miners using explosives.

He thought that the old Southfield workings must have been pushed farther than the surveys indicated, resulting in the current operation proceeding beyond its presumed safety margin.

At South Wellington, as in the aftermath of tragedies everywhere, “a morbid crowd of spectators flocked to the mine from Nanaimo and Ladysmith within a few hours after the flood occurred, while this morning another contingent of the curious invaded the little hamlet, its heavy pall of mourning disregarded by those who were anxious to get a glimpse of the flooded mine...”

(In censuring what he dismissively termed a “contingent of the curious,” this unnamed reporter makes no allowance for the fact that the people of Nanaimo and Ladysmith, both coal mining communities, had known their own colliery disasters. Is it not possible that they were drawn to South Wellington in her sorrow not out of morbid curiosity but from empathy? And isn’t it highly likely that they knew some of the miners involved?))

“All talk of funerals is idle until the water has been pumped out of the mine, but the sudden tragedy has thrown South Wellington into a stupor from which it has not yet recovered. The recent riots, the coal strikes [the famous Great Strike of Vancouver Island coal fields, 1912-1914] and then the fire which swept the mining town [the year before], were just being overcome, so that the latest horror is a particularly severe blow.”

One of those who survived the horror below was Bob Fairish, who’d been ill on Monday night and hadn’t reported for work with the morning shift on Tuesday. Had he gone to work he undoubtedly would have been among those drowned as it had been his turn to work in No. 3 level. His roommate, Billy Irving, died with the others.

New Zealander Ollie Legrion [Olaf Ligeran] had tried to get Fairish up that morning, he said, by asking him to fix his lamp before he left for the mine. “But I refused to budge.

“It seems impossible to believe that all of my good pals have gone, and I can only thank heaven that I was spared...I feel that I have been born under a lucky star,” he concluded.

A lucky star, indeed, as this hadn’t been the Durban miner’s first close call underground. Six years before, he’d been entombed for 38 hours in a mine in the old Country. But this latest disaster had cost him “three boon companions”.

One other man who’d been blessed with a lucky star was Benjamin Zeziol [sp?] initially believed to have been entombed with the others because he hadn’t appeared for work Monday morning. Confirmation of his safety lowered the official death toll to 19.

William Gibson who’d survived the Extension explosion of six years before that killed 32, had gone to work—and died.

By Thursday, February 11, three days after the disaster, the full impact of the tragedy registered itself upon the residents of South Wellington when “grief unabounded” replaced the stoic silence of the first two days.

Although not the Island’s worst colliery disaster in terms of lives lost, the PCM flood of 1915 was yet another grim chapter in the history of coal mining in this province. Sadly, it would be followed by others—beginning just three months later with an explosion that killed 22 miners in the Reserve Mine, Nanaimo.

* * * * *

All of which begets the obvious question, how—how did the morning shift working in No. 3 level punch through into the abandoned, flooded workings of the Southfield Mine? Yes, it’s accepted as fact that fire boss Nellist fired the fatal shot that broke through the wall of coal separating the two mines.

But the they were supposed to be no less than 170-400 feet apart, considered to be an absolutely safe barrier. Had the operators of the long finished Southfield strayed over their recorded boundaries, as mines inspector Newton speculated?

Or had somebody screwed up?

The sad answer, and its legal aftermath, next week in the Chronicles.

(To be continued)

* * * * *

Some years ago popular Island musician David Gogo, posing here with Cowichan’s Old Stone Church in the background, wrote a tribute to his great grandfather Sam Wardle and the lost morning shift of the PCC Mine. She’s Breaking Through won a Juno nomination. (You can play it on YouTube.) David also performed a benefit concert and worked to save the Pacific Coast Coal Mine Co.’s headframe/tipple at Morden Colliery Provincial Park.

At the site of the PCCM, during one of the many Black Track Tours I gave to raise public awareness of the need to save the then-neglected Morden head frame from eventual collapse, I presented David with a miner’s tag from this historic mine with its emotional family tie.

These miner’s tags are from Extension but those of the PCC Mine are similar. David Gogo has acquired many mining artifacts in his extensive travels as a professional musician, but the tag from the mine that killed his great grandfather Sam Wardle is special, he says.

Lost PCC miner Sam Wardle. —Courtesy Helen Tilley

(To be continued)