Pacific Coast Colliery - Doomed Miners' Day in Court (Part 3)

Of all the coal mining disasters in Vancouver Island’s history that of the Pacific Coast Coal Mine in South Wellington stands out on two counts.

There’s little to be seen of the PCCM Colliery today and a public hiking trail passes right through the old town site. Here, Island coal mines aficianado Jennifer Goodbrand checks out the sign warning of gas escaping from the mine’s filled-in fan shaft.

First, that it was caused not by the usual suspects, gas, explosion or cave-in, but by flooding.

Second, that, for once in an industry that all but accepted dangerous working conditions and their consequences as the cost of doing business, criminal charges were laid.

* * * * *

As we’ve seen, on the morning of Feb. 9, 1915, PCCM fireboss David Nellist fired a charge in No. 3 north level of No. 1 slope that broke through into the flooded workings of the old Southfield Mine.

The sudden inrush of water filled the South Wellington Colliery to a depth of 600 feet and drowned 19 men, including manager Joseph Foy who’d been on the surface but rushed below when informed of the breakthrough.

Company management had always known of their mine’s proximity to the Southfield workings which had been abandoned in 1893, just as they knew their other immediate neighbour, the Alexandria Mine, closed in 1901, was also flooded.

But accurately surveying underground mines, which resemble an inverted anthill with their levels and stopes, was long established practice, and their information about the Southfield was also taken as a given—they had a set of plans of the old workings.

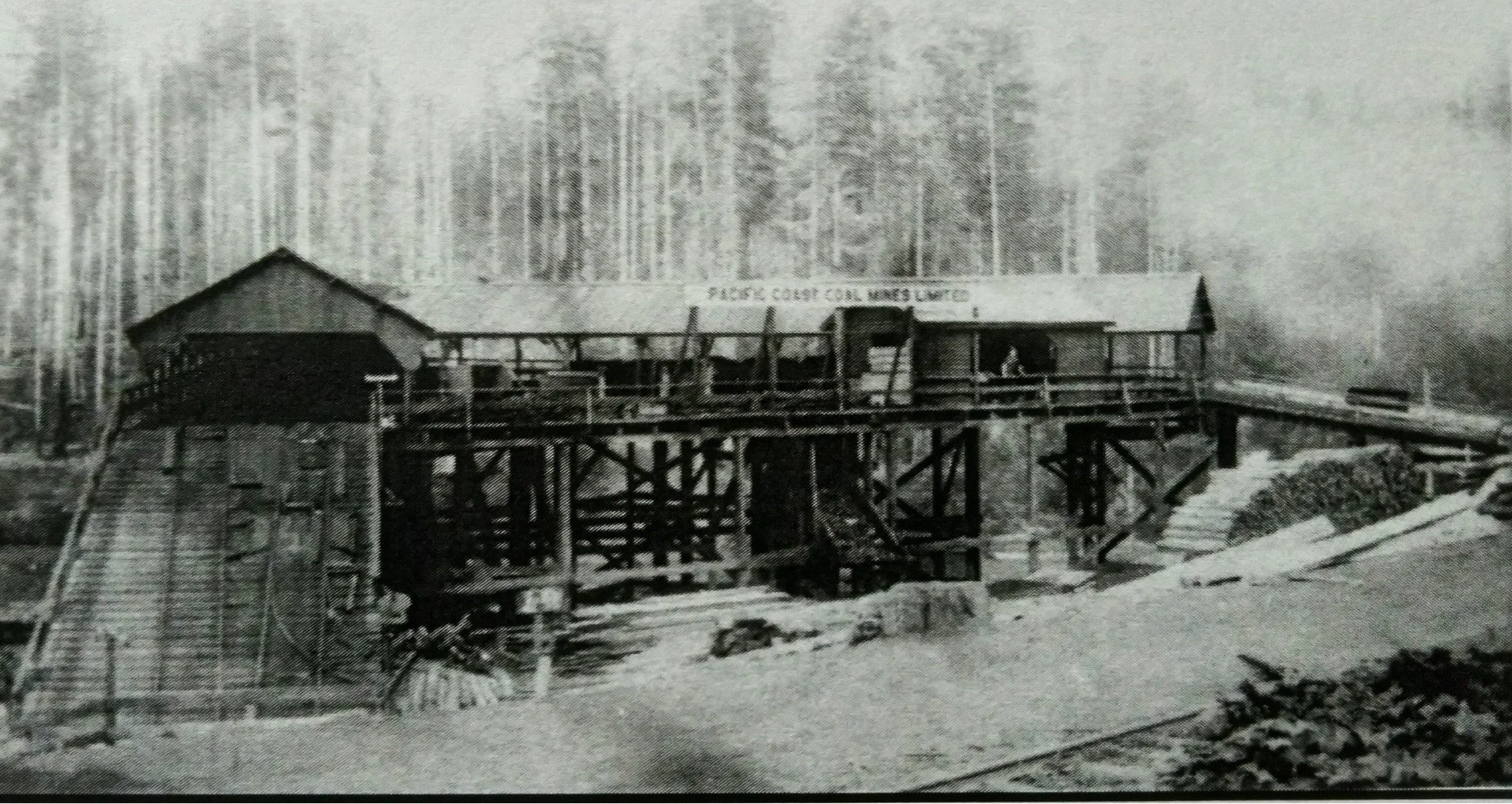

The PCC Coal Mine at South Wellington; note what appears to be at loaded ore car going up the ramp on the right. —Courtesy Helen Tilley

The Western Fuel Co., successor to the New Vancouver Coal & Land Co., owned the Southfield and its manager Thomas Stockett had graciously given PCCM manager George Wilkinson a copy of the blueprint back in 1908. Management of the Alexandria, closed in 1901, had refused to share their plans of their underground workings but that has no bearing on the tragedy of 1915.

Manager Foy was absolutely convinced that his men were all of 440 feet from the Southfield; after all, regular mining practices accepted a minimum of 50 feet to be a sufficient safety barrier. So sure was he of this critical fact (his life and those of his men depended upon it) that, less than a week before the breakthrough, he guided provincial mines inspector John Newton on an underground tour to make his point.

As Newton reported in his report to the Ministry of Mines:

“...I examined this mine on February 3rd, six days previous to the date of accident, and on visiting No. 3 North level, Diagonal slope, No. 1 mine. I remarked to Jos. Foy, the manager, who was accompanying me, that the places were very wet, and asked how far they were from the Old Southfield mine, and if be thought that the water was coming from that source.

“He answered: ‘No, it was coming from an old swamp on their own property, about 300 feet from their boundary-line.’ To prove this statement, when we got into the face of the level, close to the boundary pillar, he pointed to the roof, which was perfectly dry. He said: ‘Have no fear about Old Southfield, we are from 500 to 600 feet below any workings of Southfield mine; this is all solid coal—in fact, it is the only coal we have got, and we expect to have twenty or thirty places in this section before long, expecting to get all the coal below Southfield workings; but wait until we arrive at the surface and I will show you on the plan where we are as regards the Southfield.’

“When we arrived at the surface we went to the engineer’s office and examined the plan of their workings in No. 3 North level in relation to that of Southfield. Foy scaled the plan across, which showed a distance of 440 feet to the nearest place shown on the Southfield plan. He then showed me what they proposed to do in this section; he was going to run No. 3 North level up along the side of the boundary pillar to connect with two slopes coming down from No. 4 West level at a point 200 feet below the Old Southfield line.

“I then told him, when he reached a distance of 50 feet from his proposed line, be must have boreholes ahead, and flank holes to the side to make sure in case of any accident.

0He assured me that he would carry out these instructions to the letter, as he did not want to take any chances of losing any lives. He said it did not pay the company or anybody else to take chances, but at the present time there was nothing to be afraid of, as they were too far from the danger-line, but be would take all precautions necessary to guard against any danger from the Old Southfield workings...”

So, if surveying mines was an exact science and the PCCM had the plans to the Southfield, what went wrong?

Inspector Newton’s first surmise upon news of the flooding was that the operators of the Southfield had exceeded their boundary, putting them into the PCC’s property. But the answer soon became apparent—had, in fact, long been known—but, it appears, overlooked or forgotten during a period of corporate restructuring of the South Wellington Colliery.

0Back in the 1880s, the owners of the Southfield had followed the English custom, using the Gunters chain measurement of 132 feet to the inch for their scale. But, in 1911, B.C. mines had adapted the North American scale of 100 feet to the inch on a blueprint (as had the adjoining Alexandria Mine). It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to see the resulting cumulative effect over any given distance between 132 and 100 feet.

0mong those who left the company during the corporate musical-chairs of 1912-1914 was draftsman W.A. Owen who’d converted the Southfield plan from chains to feet; he’d resigned in July 1911 and had had two successors by the time of the tragedy. Supt. Wilkinson also departed, in January 1913, immediately followed by Manager Devlin who was succeeded by Joseph Foy then R. Richardson Roaf then by Foy as both superintendent and manager.

In the after-the-fact opinion of the Dept. of Mines, “In these many changes of officials it appears that the tracings containing the enlarged scale of the Southfield workings were replaced with new tracings on which the Southfield workings were not shown, and the old tracings were stored away in a drawer in the engineer’s room.”

Stored away in a drawer in the engineer’s room!

This initial suspicion may have been circumstantial, perhaps even speculative, but it was good enough for Chief Inspector of Mines Thomas Graham, who later wrote in the Department’s 1916 Annual Report:

“...Inspector Newton...forwarded to the Department a blue-print he had received from J. H. Tonkin, the general manager of the Pacific Coast Coal Mines, Limited. 0n comparing this print with the plan of the abandoned SouthfieId mine, it seemed evident that the company had been using on their most recently made mine-plans a direct copy of the adjoining Southfield mine (to a scale of 132 feet to the inch) instead of the enlarged plan to 100 feet to the inch, and that if a proper enlargement of the South&Id mine plan was applied to the plan of the Pacific Coast Coal Mines, Limited, the abandoned mine would be placed in such relation to the workings of the South Wellington mine as to show that it was probable that No. 3 North level had broken through into the Southfield workings, allowing the water to rush in, with the fatal results described.

“...This seemed a likely explanation of the cause of the disaster, but its accuracy was dependent upon a confirmation both of the old survey and plans of the Southfield mine, and also those of the recent workings of the South Wellington mine, the resurvey of which was impossible until the water was pumped out of the mines.

“Whilst in my own mind I had little doubt as to the substantial accuracy of [existing] surveys and plans, and therefore of the explanation of the accident, I did not feel justified in making such charge public without the confirmation of a resurvey.”

“I, however, at once verbally informed the Minister of Mines of my belief, and also of the impossibility of proving my suspicions, and, under date of March 4th, 1915, I made an official report of these facts in a letter to the Honourable the Minister Of Mines.

“In view of the absence of actual proof of my suspicions, it was deemed advisable that such suspicions should not be made public until they were verified by actual surveys, to which end we decided that as soon as practicable a competent mine surveyor would be appointed to make a resurvey of both properties, and an investigation held under the ‘Public Inquiries Act.’

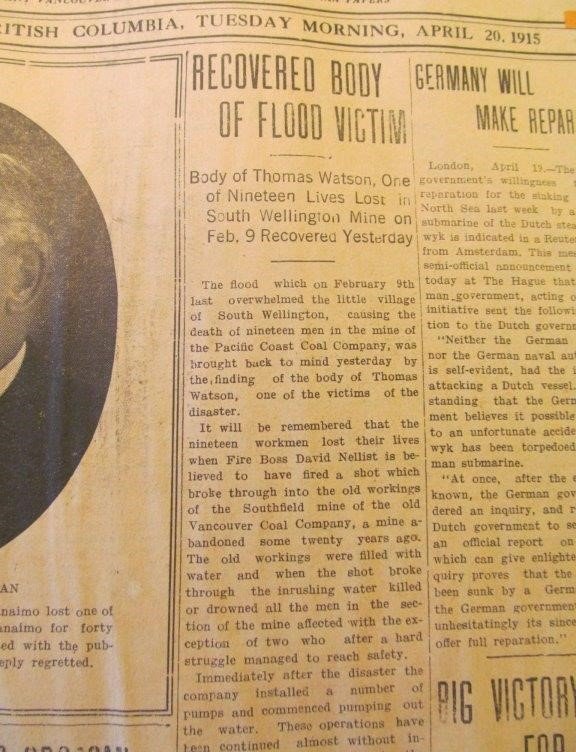

Recovery of the bodies took several months. —Courtesy Helen Tilley

“In the meantime some of the bodies were recovered and a Coroner’s inquest was held at Nanaimo on May 17th, 1915, at the opening of which the writer announced the decision of the Department to have a survey made as soon as the mine was unwatered, and that an investigation would then be held under the ‘Public Inquiries Act.’

“In view of this decision and the fact that my suspicions were still unconfirmed by survey, the writer did not deem the plans important to the Coroner’s inquest.”

Personally, Graham had little doubt as to the accuracy of the Southfield blueprints: “It will be noted that the Southfield mine was abandoned and flooded long before the present owners came in possession, and that their knowledge of the property was confined to the plans on file in the office and left there by the old company, but, judging from inference, little doubt existed as to the accuracy of these plans, as whenever the surveys made under the management of the old company bad been checked in the properties still working, they had been found to be substantially correct.”

As we shall see, Graham—who’d been superintendent of the Western Fuel Co. until he joined the Ministry of Mines—would be severely criticized and find himself in a courtroom for this decision to keep his suspicions to himself.

Late in May, British Columbia land surveyor D.B. Morkill was commissioned to make the survey and report directly to Mr. Justice Murphy who’d been appointed to hold a public inquiry. To Graham’s satisfaction the Morkill survey “proved that the plans of the old Southfield mine and also the recent plans of the South Wellington mine were substantially correct, leaving no doubt that the accident was caused by the improper use of a direct copy of the Old Southfield plan, instead of an enlargement of such plan to a scale of 100 feet to the inch, in conjunction with the South Wellington Mine plans.”

(Ironically, the plans of the Alexandria Mine, 1884-1901, filed with the Department of Mines and scaled 100 feet to the inch, showed that the Dunsmuirs, owners of the Alexandria and the E&N Railway who’d fought and lost a years-long court battle to deny settlers mineral rights to lands they’d occupied before the railway was built, had pushed their mine to the limit—and beyond.

(“...The workings of this mine had been extended so as to material]y encroach upon the seam lying under the surface of the property now held by the Pacific Coast Coal Mines, Limited, the owners of the South Wellington mine..”)

Which brings us back to the key question? How did the PCCM’s managers come to use the antiquated set of plans of the Southfield Mine with their scale of 132 feet instead of 100 feet to the inch?

What a coincidence that Chief Inspector Graham, when still working for the Western Fuel Co., had been “the medium through which a strip of the blueprint of a tracing from the original Southfield plan was given to Mr. Wilkinson, the manager of the South Wellington Coal Mines, Ltd.” This was the plan drawn by draftsman Owen that “showed clearly that it was to the scale of 132 feet to the inch,” the plan that had been converted to the scale of 100 feet to the inch.

This accurate underground chart of the old Southfield Mine “was shown on several tracings and blue-prints found in possession of the Pacific Coast Coal Mines, Limited, after the accident.”

Somehow, during the corporate manoeuvring of 1912-1914, the plan with the correct scale was filed away in a drawer and, in blissful innocence, Manager Joseph Foy had directed his men to their deaths.

How critical was the difference in the scales of the two plans? It made the Southfield workings appear to be 752 feet farther west in relation to the South Wellington workings than they actually were.

752 feet!

So who was responsible? Whose “carelessness” had led to the deaths of 19 men? Whoever filed away the correct Southfield plan in a drawer? Manager Joseph Foy for working with the wrong scale?

According to the B.C. Attorney-General there were two culprits, PCCM’s Managing Director J.H. Tonkin—and Chief Inspector of Mines Thomas Graham!

(Conclusion next week)

* * * * *