‘Return to Sender’ – Around the World, Museums Are Relinquishing Priceless Antiquities to Their Rightful Owners

After generations of resistance, the dominoes are falling almost weekly, it seems.

I’m referring to the sometimes reluctant return of artifacts, ancient and modern, in this New Age of cultural awareness and racial and ethnic sensitivity.

In Canada we’re driven by the tsunami that has resulted as a consequence of Truth and Reconciliation—a belated admission that our colonial mindset and governance of two and a-half centuries must change.

You’re seeing this again and again in the news so I’ll not dwell on it here.

‘Coppers’ were among the most prized treasures of B.C. First Nations. The Canadian government confiscated them under threat of criminal prosecution. —Author’s Collection

My intent this week is to focus on the growing trend of museums to surrender the priceless antiquities of ancient worlds—treasures often held by museums far from their creators and national origins—but particularly those much closer to home, right here in British Columbia.

To set the stage, here are the latest news items by their headlines:

l B.C. First Nation arrives in Scotland, asks museum to return totem pole taken in 1929

l Royal B.C. Museum returning museum to remote First Nation

l After 138 years, house post returning to Gitxaala Nation

l Nuxalk Nation celebrates return of totem pole from Royal B.C. Museum

Farther from home, some of these returns, or repatriations as they’ve been termed, are momentous:

l Mi’kmaq regalia to return home to Nova Scotia after 130 years in an Australian museum

l Museum: London, Athens could share Parthenon Marbles in deal

l Swiss museum returns Indigenous relics

l Chief Poundmaker’s pipe, saddle bag returning from Royal Ontario Museum to descendants

l Rare, centuries-old jewelry returns to Cambodia

l With eye on Britain, Greece welcomes back artifacts

In short, we’ve come a long way from banning, seizing and looting—and we’re not finished yet.

* * * * *

By the turn of the last century, many of British Columbia’s First Nations were in complete disarray, decimated by repeated smallpox epidemics and other devastating social consequences of their encounters with European colonial policies. According to https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/British_Columbia_First_Nations, some tribes had been reduced by up to two-thirds!

Adding insult to injury, these sad statistics weren’t, initially, even recorded because of the racially discriminatory practices of the Dominion and Provincial governments. Indigenous people and those of colour were excluded from the Births, Marriages and Deaths Act of 1872. It wasn’t until five years later that the Act was amended to include “all races and nationalities, including all Indians and persons of Indian blood, Chinese and Japanese”.

In 1916 the Act was again amended, this time to allow the province’s Indian Agents to file monthly forms that were kept separate from those used for the general populace. Even after 1943 when the reporting of First Nations vital statistics became mandatory, the records were done on separate forms and the files segregated.

Not until after 1956 did records of Indigenous citizens become part of Vital Statistics’ mainstream.

* * * * *

To get back to our theme, the growing trend towards the repatriation of historical treasures to their original owners...

The exquisite artistry of B.C. First Nations had been evident to European visitors from the start. Long before Indigenous carvings achieved popularity with tourists, the elaborate decoration of totem poles and masks and other regalia was an essential part of the culture of many coastal tribes.

With the ever-growing contacts and trade between newcomers and Indigenous residents, then the rapid and devastating decline of the latter, the acquisition of these cultural icons began. Individual collectors were soon followed by those acting on behalf of European and American museums who began to pursue Native art and artifacts systemically on the premise of “saving” them from a dying race.

What likely began as a trickle became a flood when the federal government outlawed the potlatch. Not only was the ceremonial giving away of goods now banned but so was possession of the religious and cultural icons that were treasured by individuals, families and tribes. These were to be surrendered to the Dominion for a token remuneration.

Photos of some of these seized cultural treasures literally blow one’s mind today!

See also WHEN NAVY CANNON ENDED CHEMAINUS POTLATCH

* * * * *

The United States Coast Guard considers Cdr. Dorr Francis Tozier to be the father of wireless communication in that service and a legend in his own lifetime. Certainly his career in the U.S. Revenue Service was as colourful as they come.

According to https://laststandonzombieisland.com/tag/dorr-francis-tozier/ “the Georgia-born Tozier received his commission from Abraham Lincoln one month before the president’s assassination and was awarded a Gold Medal by the President of the French Republic ‘for gallant, courageous, and efficient services’ in saving the French bark Peabody in 1877, while the latter was grounded on Horn Island in the Mississippi Sound.”

Cdr. Dorr Francis Tozier, United States Revenue Service. —www.findagrave.com/memorial/2503944/dorr-francis-tozier

He’s also remembered in B.C. for his having helped to solve the mystery of HMS Condor which vanished at sea with all hands in a storm in December 1901. Because the only man-of-war to be lost on the Pacific Station had sailed from Esquimalt for Hawaii it was weeks before she was posted as missing followed by months of searching for evidence of her foundering.

Although the commander of an American government vessel, Cdr. Tozier assisted the Royal Navy in its broad search for wreckage and it was Cdr. Tozier who found her whaleboats, a sailor’s cap and a broom in possession of a west coast Vancouver Island chieftain. Needing the boat as proof of the Condor’s loss he negotiated for the craft but its new owner rebuffed all his offers for a trade.

Tozier was at a loss as to how to proceed when the chieftain pointed to his dress sword and made it plain that that was his price. Reluctant though he was to surrender his blade, Tozier agreed and the deal was sealed. It took the British Admiralty five years to replace his sword and it took a Congressional Act of Congress for Tozier to be granted permission to accept it.

Cdr. Tozier is also remembered on B.C. nautical charts; Tozier Rock in Saanich Inlet is a permanent reminder that his ship, the U.S. Revenue cutter Grant, grounded on the previously uncharted underground hazard in 1901 and was hung up for days while awaiting rescue by two of her sisters.

U.S. Revenue Cutter Grant. —United States Coast Guard

Yet another claim to fame, this one relevant to today’s tale, is Tozier’s penchant for collecting Indigenous art during the Grant’s coastal tours. These nautical perambulations allowed Tozier access to out-of-the-way and isolated First Nations communities. An American magazine, Columbia, claimed in a 1995 article that B.C. Natives were as eager to trade their traditional handicrafts as their forefathers had been to trade pelts for white men’s tools and trinkets.

Tozier, as did others, viewed B.C.’s original inhabitants as a vanishing race, and their carvings, masks, baskets and other cultural and religious regalia to be in danger of disappearing. He collected prodigiously until his retirement from the Revenue Service in 1907.

The result of his acquisitions over the years, whether by trade or cash—and we can only speculate as to how ethically he conducted these transactions—was nothing less than staggering: “...Some 10,000 artifacts including 2,500 baskets, 100 stone chisels and axes, carved jade pipes, harpoons, war clubs, knives of copper, ivory, shell and iron, a war canoe, and ‘12 mammoth totems, each weighing between 600 to 20,000 pounds.’

“In all, the collection weighed 60 tons and required 11 large horse-drawn vans to move to the Washington State Art Association’s Ferry Museum in 1908[!]”

Cdr. Tozier died in 1926 and, come the Great Depression of the 1930’s, the Ferry Museum became financially strapped, was dissolved and his collection was disposed of, piecemeal, with many items being sold on the international market. Only a fraction of the Commander’s astounding treasure trove of Indigenous artwork made it to the Smithsonian Institute’s National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, DC. These likely are of ‘American’ origin, meaning they’re the products of First Nations artisans within the borders of the continental U.S. and Alaska.

Should you Google Cdr. Dorr Francis Tozier you’ll find several illustrated posts by what’s now the National Museum of the American Indian. They show examples of some of Tozier’s “rescues” in the formally named Tozier Collection. These aren’t on open display, incidentally, but can be viewed in person by appointment.

Their provenance, happily, can be viewed digitally, such as the story behind, for example, a Puget Sound Salish “figure:”

Collected between 1894 and 1907 by Captain Dorr F. Tozier (1843-1926, associated with the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service); Tozier's collection was purchased in 1909 by the Washington State Art Association (Seattle, Washington); when the Association defaulted on its payments for the collection.

In 1916, it became the property of the Seattle Land Improvement Company, owned by Fred E. Sander (1854-1921); in 1917. George Louis Berg (1868-1941, director of the Washington State Art Association) negotiated on Fred Sander’s behalf to sell the collection, which was purchased that year by MAI using funds donated by MAI’s Board of Trustees.

So much for Cdr. Tozier who, layman though he was, had an unerring eye for exquisite artisanship, and whose apparent altruism culminated in his “saving” much of a priceless heritage. Those who, today, criticize his actions, may be asked in fairness: Had he not done so—what would have happened to many of these treasures?

* * * * *

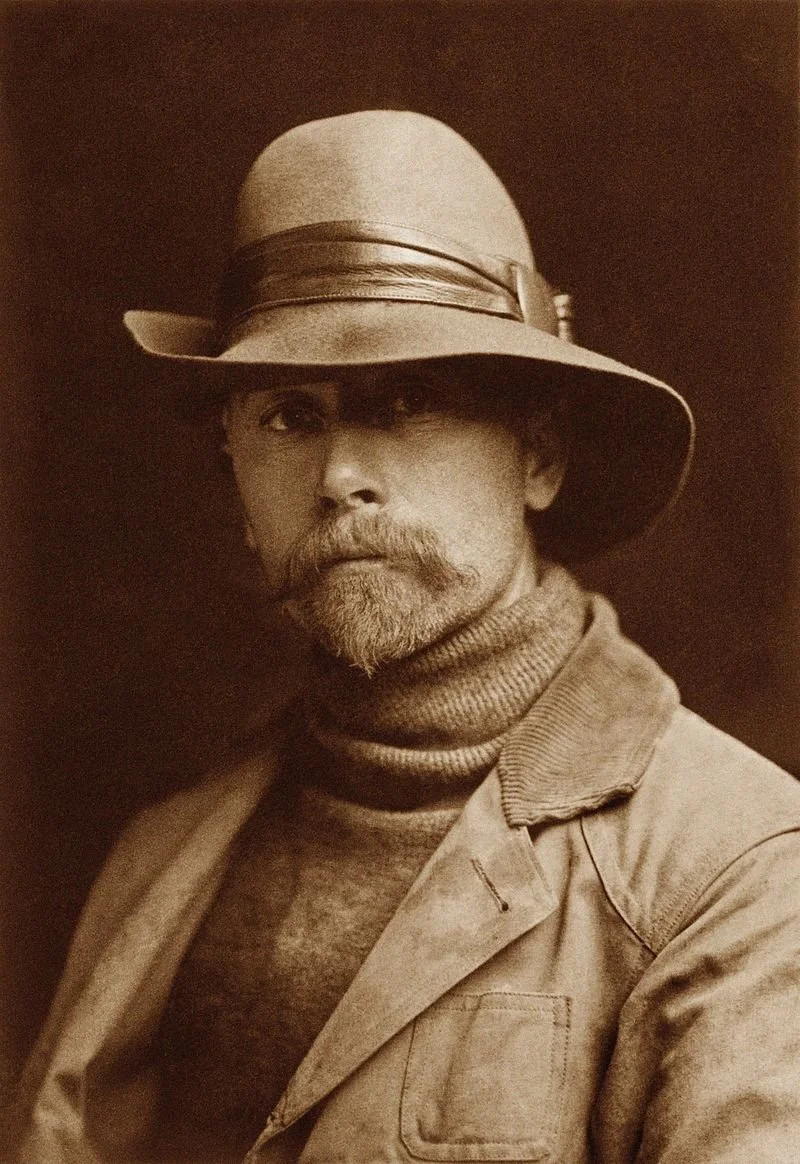

There’s another leading gatherer of B.C. Indigenous art who bears mention, this one with the highest academic credentials. In fact, German-born Franz Boas (1858-1942) is considered to be the Father of American Anthropology.

Franz Boas, pioneer anthropologist and wheeler-dealer in antiquities on the side. —Wikipedia

How ironic then that he, of all people one might think, wasn’t above wheeling and dealing in Native artifacts—even human bones. Anthropology, it seems, didn’t pay well (at least in the early years) and he, like everyone else with a family, had to make ends meet.

The son of wealthy artists, he showed an early interest in natural sciences although he majored in physics, geography and mathematics at the University of Heidelberg before turning to anthropology.

During a geographical expedition to Baffin Island he became fascinated by the culture and language of the Inuit people. Then it was more fieldwork, this time researching the Indigenous cultures and languages of the Pacific Northwest.

He emigrated to the U.S. in 1886 to work as an assistant then as a curator at the American Museum of Natural History, New York, for 10 years before becoming a professor of anthropology at Columbia University, a position he held for the rest of his career and where he won international acclaim as one of the leading anthropologists of his time.

While still in university in Berlin he’d been introduced to members of the Nuxalk Nation of British Columbia and he first became intrigued by Pacific Northwest Indigenous culture. Enough so that he spent three months here, studying the Kwakiutl and other provincial tribes, before being offered a job in the U.S. He made five more trips to the Pacific Northwest over the years.

There’s so much more to the Franz Boas story but not today as our interest is in his role in acquiring B.C. Native art.

He was appointed as first assistant to the team of more than 100 that was organized to prepare for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition (the first World’s Fair honouring the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbia’s arrival in the Americas).

It was Boas who conceived the idea of having real Inuit and First Nations representatives display the differences between their cultures and that of cosmopolitan Fair-goers by demonstrating their “natural conditions of life”. He “arranged for [14] Kwakwaka'wakw aboriginals from British Columbia to come and reside in a mock Kwakwaka’wakw village, where they could perform their daily tasks in context. Inuit were there with 12-foot-long whips made of sealskin, wearing sealskin clothing and showing how adept they were in sealskin kayaks...”

It’s to Boas’s discredit that, once the Exposition ended, he virtually abandoned the transplanted Inuit to their own devices and, within a year, four had died of tuberculosis.

His interest lay in the ethnographic material collected for exhibition which he appropriated to become the basis of the newly created Field Museum in Chicago—with himself as the curator of anthropology. Meaning that he could be cynical when it suited him or when he felt financially pressured—as he’d been when he first arrived in the U.S. and supplemented his income by selling Native artifacts and human remains.

Were any British Columbia treasures involved in these purely business sales? Will we ever know?

That said, there’s no denying Franz Boas’s contribution to science and to history. The illustrious Margaret Mead considered him to be “the father of American anthropology and the greatest anthropologist who ever lived”.

* * * * *

Which brings us to a third historical giant who spent much of his lifetime preserving North American (including British Columbia) Indigenous culture—through the lens of his camera. Edward S. Curtis (1868-1952) took 10’s of 1000’s of photos that have captured a vanished way of life as no others in anthropological fields have ever done.

A self portrait of renowned ‘Indian’ photographer Edward S. Curtis. —Wikipedia

He’s best remembered for his classic book, The North American Indian, to which he’d sold the rights when destitute in his later years.

Posterity has to be grateful that many if not most of his photos were published in book form. That’s because when wife Clara, who claimed abandonment and non-payment of alimony, was granted full possession of all his negatives in a divorce settlement, the embittered Curtis and his elder daughter Beth broke into his studio and smashed 1000’s of glass negatives.

* * * * *

All of which brings us to the present and, in February, the return of an 1880’s totem pole to the Nuxalk people of Bella Coola territory. It took a crane and the removal of a wall of the Royal B.C. Museum to lower the massive pole onto a flat deck truck to begin its homeward journey.

As noted at the start of this Chronicle, museums around the world are having to come to terms with some of their most prized antiquities. It will be interesting to see if more B.C. Indigenous treasures are finally returned to their creators.