Robert ‘Eugene’ Swanson Was All-Time Whistle-Blower!

Performed at Chemainus Theatre amid rave reviews, the Other Guys Theatre Company’s Good Timber was “a terrific local history lesson” built around (to quote the Cowichan NewsLeader Pictorial) “the logging camp poems of former Chemainus sawmill worker Robert E. Swanson [featuring] many historic clips of Cowichan’s logging days.”

Bob who?

After a career in the lumber industry Bob Swanson became B.C.’s chief inspector of railways. Off-duty, he wrote poetry, invented things and made whistles–big whistles–for railways, for ships, for lighthouses, for at least one major Nanaimo coal mine and the Duke Point pulp mill. Although born in the romantic age of steam, he’s credited with (or cursed for) having invented the air horn ‘chime’ used by diesel locomotives.

No one who was born before the late 1950s will ever forget the wonderful sound of a steam locomotive whistle; Swanson also helped to rescue the Royal Hudson from the scrap heap. --Wikipedia photo

Born in Redding, England, Bob Swanson came with his family to East Wellington, Vancouver Island, in 1907. It was there that he fell in love with trains. Dropping out of school at 14 to work in a logging camp as a whistle punk, he obviously applied his practical education on the job as he had his fourth-class steam engineer’s ticket by the time he was 17.

By 1934 he, wife Mabel and their infant daughter Sylvia were living in Kapoor, a tiny sawmill community near Sooke Lake, where he was the chief engineer.

It was “in the middle of nowhere,” Sylvia recalled some years ago. “The train went by once a week to throw us mail and supplies. There was a one-lane dirt road into and out of Kapoor. It was there he attained his further engineering degrees [five in all] by correspondence...”

The Bob Swanson mural in Chemainus. Notice the working clothes—a former business partner marvelled in later years that he’d never–not once–seen Swanson not wearing a tie.

Swanson also found time to write poetry, taking his inspiration from Robert Service, the Bard of the Yukon. Whereas Service immortalized the men and the majesty of the wintry Klondike, Swanson extolled, in Rhymes of a Western Logger, Rhymes of a Lumberjack, Bunkhouse Ballads and Whistle Punks and Widow-Makers, the wonders of the B.C. woods and the bigger-than-life men who logged them. At least 80,000 copies of his books were sold in the 1940s and ‘50s, then re-issued as a single volume, Rhymes of a Western Logger, in 1992.

(These were the inspiration for the Other Guys’ Good Timber: Songs & Stories of the Western Logger, backed up by an outstanding selection of old photos and even some grainy movie film.)

Although a journalist once described logger, poet, bureaucrat and businessman Bob Swanson as “a kind of rough-hewn West Coast Renaissance man,” he was no caulk boots and Stanfields man. As a former business partner marvelled in later years, he’d never–not once–seen Swanson not wearing a tie. The finishing touches to his personal appearance were his pencil-thin, Hollywood-style moustache and a fedora hat.

None of which matches the Chemainus mural painting of him in work clothes.

Always, the brain was hard at work, right to the very end, his former secretary describing him as a human dynamo. In fact, she said, his only visible concession to old age was his hearing, lost after 25-odd years of working with steam whistles and air horns at his remote Nanaimo Lakes testing ground, where he used a 1914-vintage steam boiler from a logging donkey for a power source. In later years, he and his two partners in Airchime Manufacturing Co. tested their products in a soundproof, echo-free chamber at their Burnaby plant.

Another of the famous Chemainus Murals depicts workers of the Victoria Lumber & Manufacturing Co. mill–among the largest in the world–anticipating the end of the shift, the whistle and Bob Swanson, its maker. The mural is situated on Cypress Street, the gleaming brass whistle is on display in the Chemainus Museum where it is among the museum’s prized possessions.

It’s believed to be “the largest whistle known anywhere. Unlike many mill whistles, this giant was never given a name, being known only as ‘The Chemainus Whistle’.

“[Its] mighty voice could be heard for more than 20 miles. Built here at the mill by Chief Engineer Bob Swanson, it started sounding shift changes in March 1940, a duty which was faithfully performed until May 1982 when the old mill was closed.

“Fed directly from the boilers by a four-inch pipe with 165 pounds of saturated steam, three whistles made up the harmonic A-Flat Major in the second inversion. Tuning the giant whistle was accomplished by phone calls at noon each day to a piano tuner in Nanaimo. Bob Swanson would adjust the bells up or down to satisfy the piano tuner’s ear.”

He was just 26 when he built his first steam whistle for the Nanaimo Lumber Co. and his whistles and horns–his ‘H5’ model was the world’s first five-chime air horn–include the Royal Hudson locomotive which he helped to rescue from the scrap heap, and B.C. ferries. They also were adapted by major railways in Canada and the United States. Swanson is better known, however, for his 1967 O Canada air horn that sounded the first four notes of our national anthem over Vancouver every day at noon, and Gastown’s steam clock.

Many know Robert Swanson today for his logging poetry rather than for his mechanical career.

Few likely credit him for having invented a fail-safe air brake system for logging trucks or for coming up with the idea for ‘runaway lanes’ for trucks descending steep hills on provincial highways.

It was a safety issue that originally prompted his work with air horns.

In the late 1940s, when most major railways were converting from steam to diesel, it was quickly noted that the diesels, for all of their power, couldn’t get it up when it came to blowing their own horn, so to speak; they lacked the necessary ooomph! Unlike the soulful sigh of a steam engine, their weak effort was compared to that of a love-sick moose. The reality was not only unromantic but ineffective in warning of a train’s approach.

As the first diesels simply couldn’t announce themselves as they approached level crossings, there were accidents including an almost fatal crash between the E&N Railway’s first diesel locomotive and a logging truck at Westholme.

When diesel locomotives came along, their first air horns were described as sounding like a “love-sick moose” and led to accidents with road traffic. It was Bob Swanson who gave them the distinctive sound that we know today. —Wikipedia Commons photo by Andrey Kurmelyov - Gallery Photoarchive copy, CC BY-SA 4.0,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=66660091

After this incident that the federal Department of Transport asked Swanson, the renowned master of steam whistles, if he could improve the air horn. He considered it as much a musical challenge as it was an engineering one and experimented with multiple horns that he called air chimes. The successful formula reproduced “a C-sharp diminished chord using five or six notes”.

Having grown up beside the tracks at East Wellington, he’d been inspired by the locomotives’ whistles which, he said years after, was “the signature of the building of Canada. That sound meant there was another human being out there in the country.”

‘Air chimes’ bearing Swanson’s patents continue to be made today, in Canada, the United States and Great Britain.

Bob Swanson made an indelible impression with those who knew him or of his work. Business partner Bill Challenger thought that he “bordered on genius. He was a most unique individual...very intelligent...also artistic... He had charisma that oozed out of every pore.”

Eminent B.C. railway historian Robert Turner thought him “an amazing character...one of those mechanical geniuses...he was really quite a wizard.” Turner marvelled that Swanson’s “sound is still heard around the world”.

It took a stroke, just shy of his 89th birthday, to end Swanson’s remarkable career in 1994. Former premier Dave Barrett didn’t think that even death could stop him: “He’s just moved on to some other project.”

In April 1995 it was reported that what was left of Swanson’s unique ‘Whistle Farm’ was being moved from its out-of-the-public’s-hearing site in the Nanaimo Lakes area to the B.C. Forest Museum (now the B.C. Forest Discovery Centre). Originally on Crown Zellerbach land, the operation, other than the donkey boiler, which was left to moulder in the bush but has since disappeared, probably to a scrapyard, was dismantled and transported to Duncan with the help of TimberWest.

* * *

Piece of history returns to city - Barry Gunn, Nanaimo Daily News

Nanaimo recovered a piece of its past this week.

The original steam whistle from Nanaimo’s historic No. 1 coal mine, gleaming brass restored to its original sheen after years of gathering dust in a Lower Mainland warehouse, will soon be on display at city hall.

A formal presentation of the whistle to the City of Nanaimo was planned for Monday’s council meeting.

It marked the culmination of some dogged detective work by Fred Taylor, beginning in 1990 when Malaspina University-College asked him about using the whistle to help publicize a play about 19th-century coal baron Robert Dunsmuir.

Swanson was known for his Nanaimo Lakes ‘whistle farm’

Taylor tracked the whistle to AirChime Manufacturing Co. Ltd. and former Island resident Robert Swanson–once known for his whistle-testing “farm” at Nanaimo Lakes.

“When I first visited there, it was old and dirty looking. In fact, it was sitting under a bench,” said Taylor.

Fortunately for heritage buffs, the whistle had been recovered after several items were stolen from AirChime during a 1990 break-in.

Swanson apparently had got the whistle from the owners of Nelson’s steam laundry on Comox Road (now Nelson’s Linen and Garment Supply), who kept it after the mine shut down in the late 1930s.

Swanson died in 1994. But after negotiating with Swanson’s estate and his business partner, Bill Challenger, it was agreed that the city should have the whistle on the condition that it not be sounded because of its age. [You can hear it on tape in the Nanaimo Museum.–T.W.]

Mayor Gary Korpan said he was pleased to see the whistle returned to the city where it saw service. It will likely be mounted and on display in the next few days.

“There was a suggestion that I should put it by the mayor

* * *

Whistle alerted miners and townsfolk of mine emergencies, and to clear streets - Nanaimo Daily News

“When that whistle blew, you knew you had five minutes to get home.”–John Cass

More than 50 years ago, the general background din of a busy port would be interrupted [by an] occasional ear-splitting blast from a ship’s horn or passing train.

But there was nothing quite like the sound of the steam whistle at Nanaimo’s No. 1 Mine, says local historian John Cass.

“It could be heard above all others,” said Cass.

The whistle would sound daily around 5 p.m. to tell miners it was quitting time; two blasts meant there was no work tomorrow, said Cass, who grew up around Victoria and Finlayson, a few blocks north of the mine’s pit head at Needham Street.

Several short blasts meant an explosion or an accident

There was also the sound everyone in Nanaimo dreaded: Several short blasts in a row meant there was an explosion or some other accident.

“When you heard that, everyone would drop everything and run to the pit head.”

An explosion at No. 1 in 1887 killed 148 [sic] men [the second worst colliery disaster in Canadian history—TW].

The mine was in operation from 1883 to 1938.

The steam whistle which has been donated to the City of Nanaimo appears to [be] the original, said Christine Meutzner, manager of the Nanaimo District Archives.

“It was blown in 1883 for that mine,” said Meutzner, adding the whistle is a valuable piece of the Island’s heritage.

The whistle was also used to clear the streets of youths in the days when the city enforced a curfew, 7 p.m. in the winter and 9 p.m. in the summer.

“When I was a young boy, we used to gather around Haliburton [Road]. When that whistle blew, you knew you had five minutes to get home. If you were caught, your parents were fined,” said Cass.

* * * * *

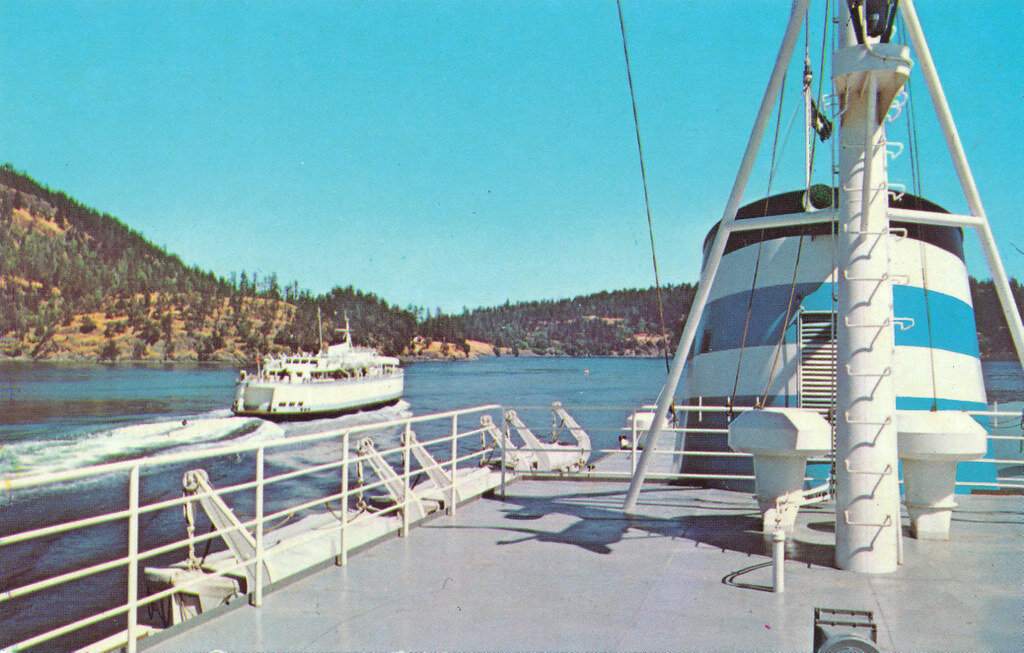

Vancouver Gastown’s famous steam-powered clock, left, is another of the ingenious creations by inventor Bob Swanson who also did whistle work for B.C. Ferries, right. —Wikipedia photos.

Robert Swanson left another legacy in Chemainus—his landmark heritage house at 2957 Oak Street. In 1994 daughter Sylvia recalled that, after he started work in 1936 as chief engineer at the Chemainus Mill, the family lived in an old grey house near the water while he bought the lot on Oak, consulted with architects, hired contractors and oversaw every detail of their new home’s construction.

Like everything else Bob Swanson did he “chose all the lumber, stucco, hardwood floors, the bathroom Italian tiles, fireplace bricks, fixtures, leaded glass windows, outside brick, every detail,” Sylvia said. It took two years to complete the landscaping when Bob took up beekeeping in the back yard.

But, hardly had they settled into their beautiful new home than the provincial government made Swanson an offer he couldn’t refuse: “In late 1939, Dad was approached...to take the job as Chief Inspector of Railways, in Vancouver,” a post he held until he retired, aged 65, and made whistles his new career.

Another of the famous Chemainus murals depicts the mill and its workers anticipating the end of the shift, the whistle and Bob Swanson, its maker. The mural is situated on Cypress Street, the whistle is on display in the Chemainus Museum.

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.