Seamen Wept as ‘Perfect Ship’ Went Down

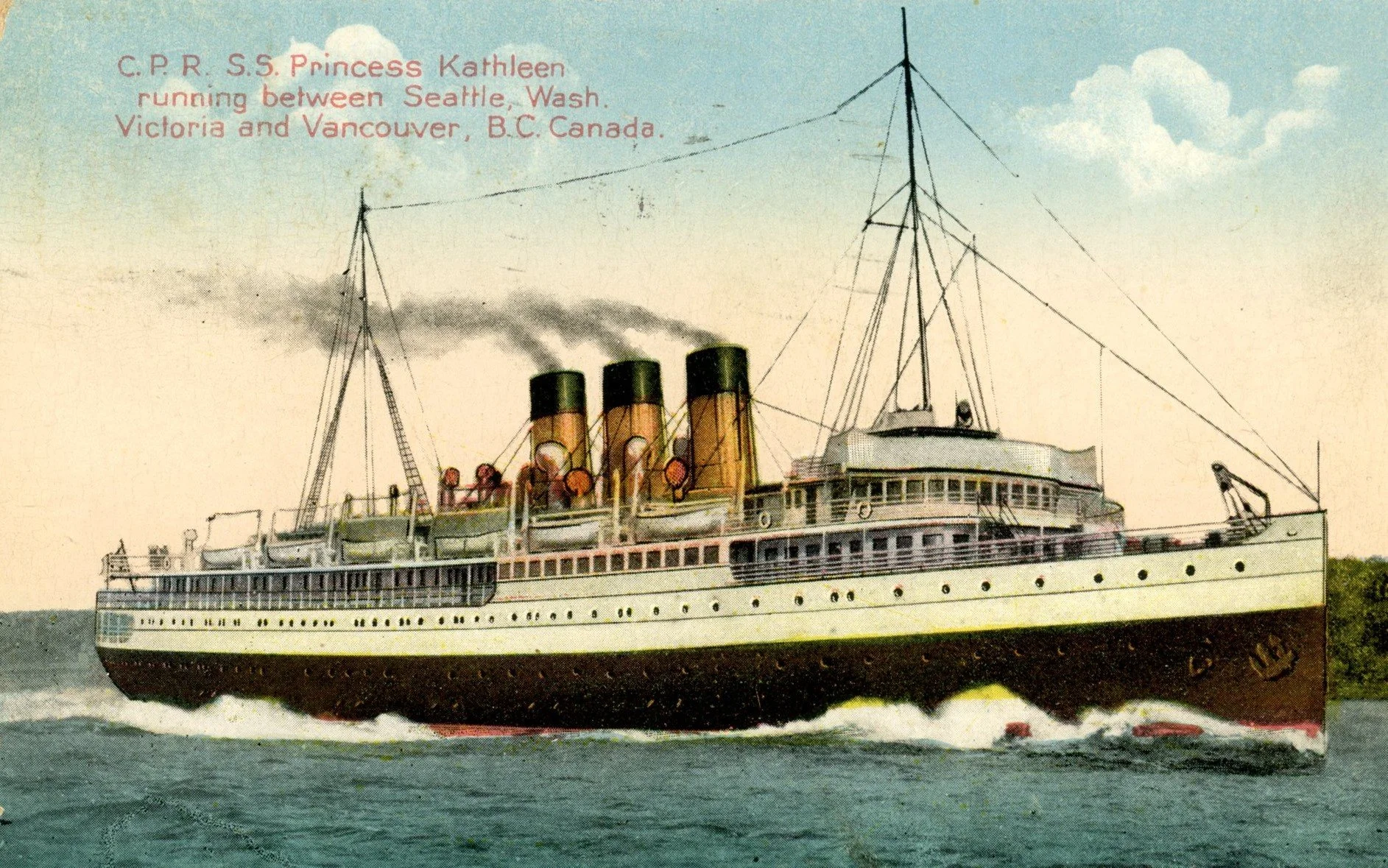

For 60 years, most provincial ferry service was provided by the Canadian Pacific Princess ships which operated on the legendary Triangle service between Victoria, Vancouver and Seattle, and between Nanaimo and Vancouver.

Among the most popular of these vessels was the Clyde-built, 6,000-ton flagship Princess Kathleen which began her coastal career on May 12, 1925.

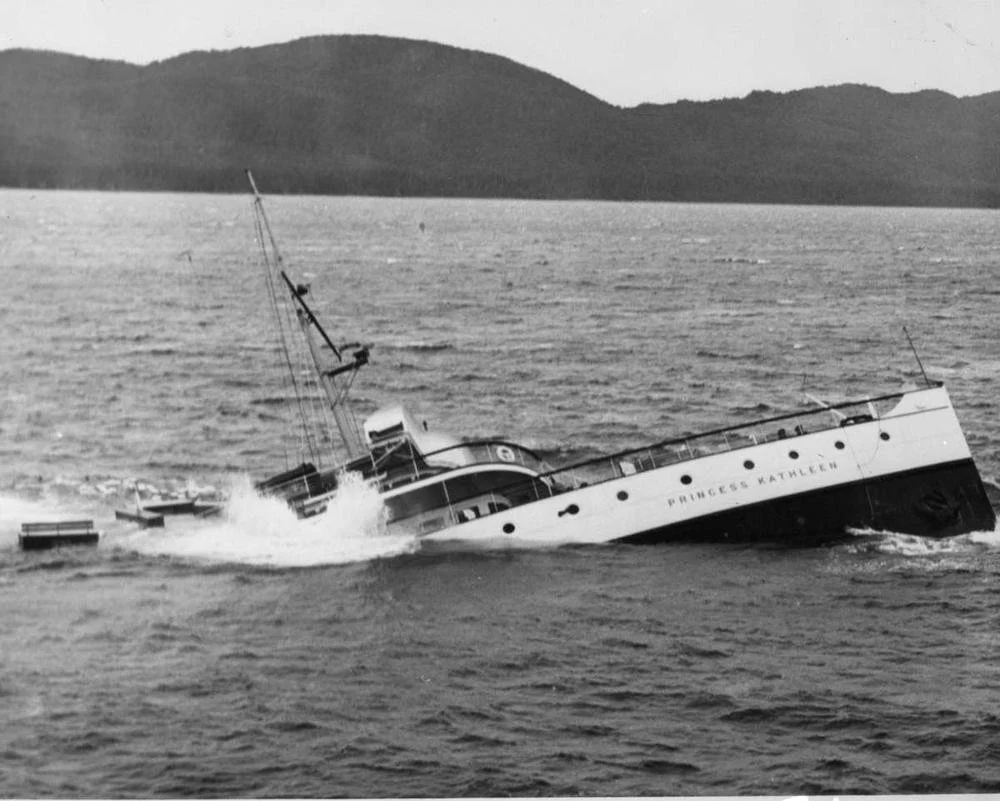

Shortly before the end, the Princess Kathleen aground on Lena Point. —BC Archives

During the Second World War, she and sister ship Princess Marguerite (See : Son’s posthumous tribute to father recalls fiery end of Princess Marguerite) were requisitioned by the government as troopships. The Marguerite was lost but Kathleen performed yeoman service in hostile seas for four years, steaming 250,000 miles and carrying almost 100,000 military personnel and civilian refugees.

The ‘Katey’ finally returned to her home berth in Victoria’s Inner Harbour at noon Aug. 26, 1946, to undergo major refit and return to passenger service between Victoria and Alaska.

But not for long. On September, 1952 while on the Alaskan route and within five hours and 30 miles of clearing Juneau for Skagway, Capt. Graham Hughes radioed that the liner was aground on Lena Point, in Favorite Channel.

At first it was thought she could be saved. But it wasn't to be so, and when she slipped beneath the waters, members of her crew wept unashamedly.

* * * * *

Many remembered her as the most beautiful liner ever to fly the checkered Canadian Pacific house flag in Pacific Northwest waters. Others vividly recalled her tragic death in cold Alaskan seas. All praised her as a grand lady, a gallant servant of her country in war and peace. Royalty from keel to mast-tip, she was Victoria's own Princess Kathleen.

A postcard of Princess Kathleen while serving on the famous Triangle Route. —Author’s Collection

Entering service May 12th, 1925, the Clydebank beauty enjoyed immediate popularity on the famous Victoria-Vancouver-Seattle Triangle Route. In the following 16 years, Kathleen reigned as company flagship, coming and going regularly with her smiling 1000s until 1939 brought war.

Around the world, graceful luxury liners were called to active service. gleaming superstructures and towering funnels which had brightened many a postcard in a happier day became drab battleship grey. Decks and staterooms which had known the carefree traveller, celebrities and royalty, now knew anti-aircraft guns and nameless 1000s in uniform.

By 1941, all the CPR’s famous white Empress liners had joined the colours, shuttling troops and vital cargo from beleaguered port to port. With November came the turn of the trim coastal twins, Kathleen and Marguerite. For Kathleen, this would be her time of glory; for Marguerite, a fiery death in a hostile sea far from home.

At 10:05 a.m. Nov. 7, 1941, the sisters, completely refitted and armed, steamed from Victoria for Royal Roads to await instructions. It would be four long, danger-filled years before Kathleen returned to home waters. Her new master was Capt. L.C. Barry, lately chief officer of the Empress of Canada.

Late that afternoon, Kathleen’s Capt. Barry and Marguerite's Capt. Leicester received their secret sailing orders. Within 10 minutes, they were navigating Juan de Fuca Strait at 15 knots, bound for Honolulu.

Hurricane force winds slowed the speedy twins to an overall 12 knots. But this was the least of the mariners’ problems. According to a company record: " The cruise, except for key ratings in deck, engine room and catering services, and the officers, had come from the Seaman's Pool and Capt. Barry was none too happy about many of the men.

“They had been shipped out from the United Kingdom to man two U.S. coastwise steamships that had been acquired by the Ministry of Shipping, but, after many delays in the delivery of these ships had been placed aboard the two Princesses. As later events demonstrated Capt. Barry's unease, which was shared by his officers, was justified."

The surly crew erupted at Honolulu when informed the ships were pausing only to refuel, that no leave would be granted. Sullen firemen had to be threatened back to their stations after a 12-hour-strike. Underway again, the sisters spent towards the Fiji islands. Reaching Suva nine days later, they fuelled and provisioned; two more uneventful weeks saw them safely anchored at Darwin.

Eight hours after clearing the Australian port, they were radioed the staggering news: Japanese bombers had just struck Pearl Harbor.

Immediately altering course for Tjilatjop, Java, the Princesses zigzagged at full speed. The calm tropical seas which had been so pleasant but hours before now held the threat of Japanese warships. The Second World War had come to the South Pacific.

Fortunately, the only aircraft encountered in the next three days were Dutch; both ships entered harbour without incident.

Kathleen’s sister, Princess Marguerite. —Author’s Collection

Due to the drastic change of world situation, it was 12 days before new orders arrived: 12 days of grief with the unruly crew. "While waiting," Capt. Barry recalled, “there was a fair amount of sickness on board: malaria, dysentery, etc. The men were getting out of hand, malingering, drunkenness, fighting and overstaying leave. Police assistance was called and some of the firemen locked up in the local jail.”

It was only through ship-side delivery by police launch that the Princesses sailed with full complements on Christmas Day.

On New Year's, 1942 they dropped anchor at Colombo, Ceylon. It was here Captain's Barry and Leicester received a belated Christmas present in the form of new crews—regular CPR Chinese from the Empress of Russia.

For the first time since clearing Victoria, Capt. Barry said with a grin in 1958, he and his officers didn't “have to sleep with wooden clubs under our pillows”!

After a brief refuelling stop at Aden, the sisters finally reached their destination, Suez. Here, Barry and Leicester had to double-talk their ships out of the unlikely duty of speedy gasoline transports.

Then it was to work in earnest.

Kathleen completed several voyages with cargo and military passengers to North African ports in the next two months, happily with little sign of the enemy. This uncertain truce ended dramatically, April 5, when a bomber roared in to attack. With Kathleen’s Bofors and Oerlikons belching fire, Capt. Barry threw the ship into a series of evasive manoeuvres at full speed and, realizing she was well-armed and fast, the lone bomber withdrew. The Princess’s baptism of fire had ended without injury.

One of her more interesting ‘cargoes,’ in the next three weeks was delivery of 1000 Italian prisoners of war to Port Sudan then, with Rommel's last assault on Tobruk, orders to be ready to assist evacuation at a second's notice. Kathleen was spared this unpleasant duty by equally unpleasant means—German tanks overrunning Allied positions almost overnight.

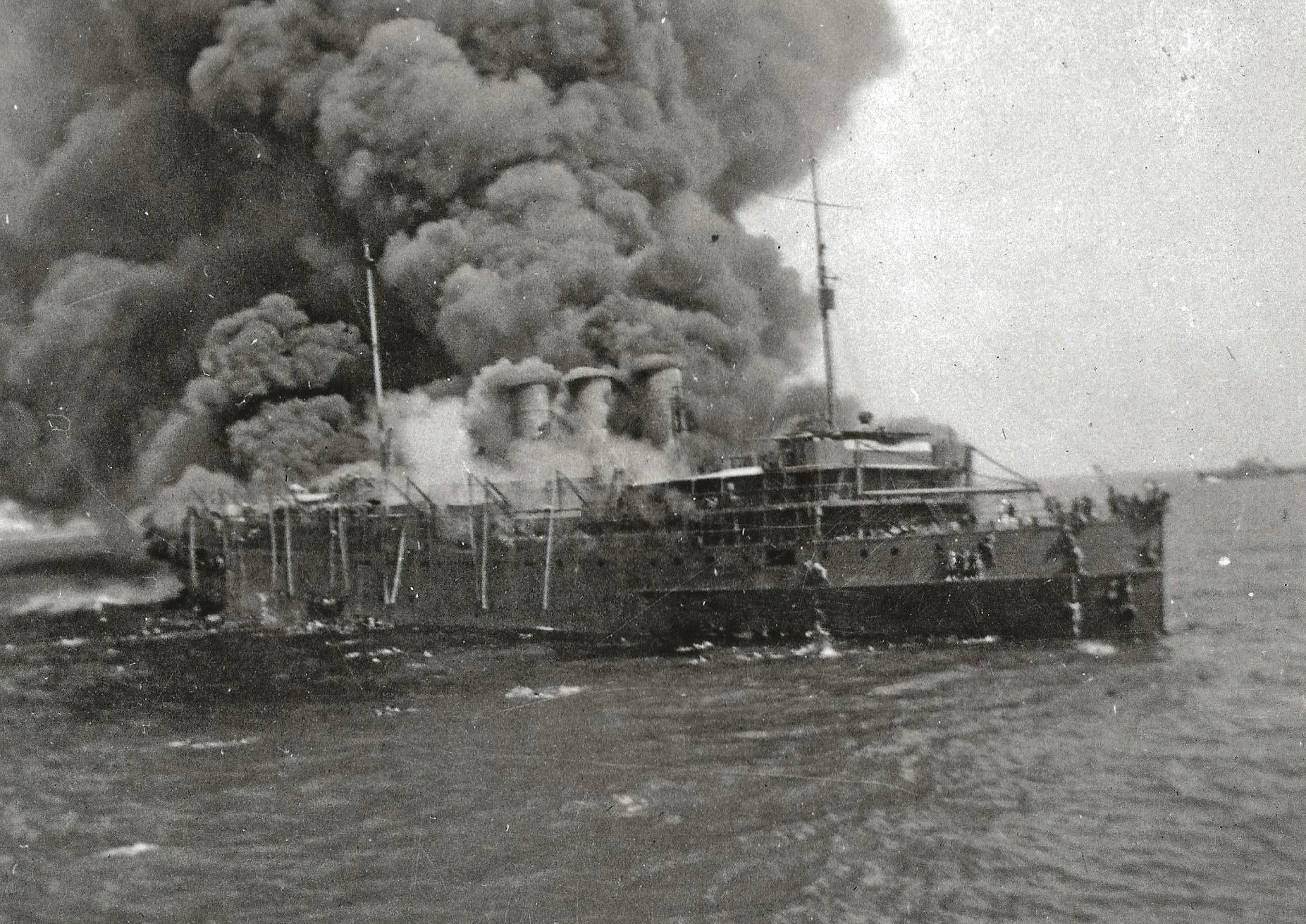

German successes in North Africa meant even more work for the Kathleen. —Lt. L. B. Davies/Wikipedia

On June 30, 1942, Princess Kathleen sadly steamed alone from Alexandria, the vital part having been abandoned to Rommel. Kathleen was the last Allied ship to leave.

Speeding to Ismalia to embark 200 officers and ratings of the Royal Navy Naval Auxiliary Kathleen sighted two submarines, believed hostile, but proceeded unmolested. Civilian women and refugees were taken onboard at Suez and during following weeks, the gaining German offensive saw Kathleen and neighbouring Allied ships under intensive air attack. Again, the Victoria lady’s luck held.

Duties became so frequent and varied, both Kathleen and Marguerite having been found “willing and able to undertake any task at any time," that an accurate record couldn’t be kept. The sisters even towed targets for RAF bombers.

Then... Kathleen was alone, poor Marguerite having gone down in flames with heavy loss of life, the victim of a U-boat.

Princess Marguerite, totally ablaze. —BC Archives

When the pendulum finally swung in favour of the Allies, Kathleen sped troops to Benghazi. Her men knew the tide had turned when they joined an enormous convoy—headed west to Tripoli. The Germans had begun their three-year-long retreat which would end in the rubble of Berlin.

There were other convoys, Kathleen’s log noting continual contact with enemy submarines and aircraft but she remained unscathed. Then it was off to the besieged Isle of Malta with fresh troops, Capt. Barry vividly remembering the “bit of a nightmare” of navigating between sunken ships for a berth.

Kathleen next began regular runs between Malta, Benghazi and Alexandria, sometimes in convoys, sometimes alone. April 6, 1943—a year and a day after her first bomber attack—her lookouts reported a formation of German planes. Happily for the Princess, the ‘Gerrie’s failed to see her, and flew off harmlessly.

A close call, was the unanimous verdict of her crew.

There were more convoys and air attacks but Kathleen maintained her exhausting schedule without mishap. In mid-September her men were treated to the inspiring sight of 10 surrendered Italian warships, including two battleships and four cruisers, being herded into Alexandria “like a flock of sheep...into the fold”.

This was a marked improvement upon a previous convoy and the torpedoing of a nearby troopship which went down in seven minutes with 800 men. Then a pleasant change of pace: ferrying Arab royalty to a two-week fete in Suez and home again. Being of noble blood herself, Princess Kathleen took it in her stride—even the carrying of livestock in accordance with Eastern custom.

It goes without saying that the troops who sailed aboard the Kathleen in wartime didn’t get to enjoy her opulent staterooms of peacetime. —Author’s Collection

The Emir Mansour was so pleased with the service, he invited Capt. Barry to the palace. After coffee and sherbet—Eastern style, of course—the Emir grandly announced he was making Kathleen a gift of 50 live sheep. Exercising admirable diplomacy, Barry gracious declined the generous officer, accepting instead, 26 bags of rice and 10 tins of ghee—rancid butter. The CPR record doesn’t mention his reaction to the latter delicacy.

Capt. Barry then formerly turned his ship over to the Royal Navy and returned to Canada with his crew for reassignment. In the two years since clearing Victoria, Kathleen had completed 131 voyages and carried 59,800 military personnel and civilian refugees 67,33 miles.

On Nov. 1st, Capt. L.H. Johnston, MBE, assumed command with his officers and crew, including many survivors of Princess Marguerite.

In the 23 months of Johnston's command, Kathleen was busier than ever, steaming to scattered Mediterranean ports. With the Allied advance gaining momentum, she roamed farther and farther afield, visiting the formerly occupied ports of Italy and Greece, Malta, Tripoli, Benghazi, Port Said, Taranto, Pieaeus, Haifa, Famagusta...

After an overdue, and all too brief, refit, the busy Princess returned to her many duties. Dubronvik, Yugoslavia, Symi and Rhodes in the Dodecanese Islands, and Suda Bay of Crete were added to her lengthening itinerary.

Kathleen even participated in the Greek civil war, exchanging 1000 Communists for 1750 Allied hostages, the Piraeus port commandant expressing the appreciation of the military authorities to Johnston and his officers for their “valuable assistance in overcoming the many problems in connection with this embarkation”.Then followed three rushed voyages to Brindisi with a division of soldiers for Tito's resistance movement.

Finally came V-E Day, but no rest for Kathleen. Now she was off to the Island of Rhodes to attend the surrender of the German garrison, and to transport General Wagner's staff to Alexandria. More grateful passengers than the Germans were Greek civilians who’d “been in camps in Egypt. For them it was a happy homecoming."

At last it came the turn of Princess Kathleen for a happy homecoming—commanded by Capt. Leicester of the Princess Marguerite who brought her home to Victoria.

In four hectic years of war, the gallant Princess had served under three decorated officers. Capt. Barry was awarded the MBE for “devotion to duty over long service in dangerous waters,” Capt. Johnston received his for leading Empress of Asia survivors safely through the jungles of Sumatra and Java to escape the Japanese, and Capt. Leicester earned his for “inspired leadership” during the sinking of the Marguerite.

When the ‘Katie’ finally returned to her old berth in Victoria’s Inner Harbour, at noon, Aug. 26, 1946, the only one on board who’d sailed with her throughout the war was Sandy, her mascot tabby cat.

Kathleen then enjoyed a $1.5 million refit, one of the largest re-conversions ever undertaken by a Canadian shipyard at that time. It was the least they could do for a valiant lady. Returned to service as a cruise liner on the Triangle Run, Kathleen found herself as popular as ever although not without incident. In August 1951, she collided in dense fog with the CNR’s smaller passenger liner Prince Rupert, narrowly escaping what could have been a major marine disaster.

The CNR liner Prince Rupert after colliding with the Kathleen. —BC Archives

Kathleen suffered a large hole just above the waterline on the port side near her forward hold, the Rupert a buckled bow. Although many of the Kathleen’s passengers had been flung from their bunks, there were no injuries and both ships proceeded to port under their own power. An Admiralty Court censured the senior officers of both ships.

Disaster came for Princess Kathleen on Sept. 7, 1952, when again on the Alaskan run.

Within five hours of clearing Juneau for Skagway, Capt. Graham Hughes radioed that the liner was aground on Lena Point in Favorite Channel. Off course, for which her chief officer was later held responsible, she’d crashed ashore two minutes before 3 o’clock, Sunday morning.

Hughes ordered the lifeboats lowered and passengers mustered in preparation to abandon ship. After waiting 45 minutes for high tide, Hughes tried to back off but the ship didn’t budge. By then the tide was beginning to ebb and the northwesterly wind, which had increased to gale force, was buffeting Kathleen’s stern towards the rocks.

Unable to keep his ship in position with his engines, Capt. Hughes ordered the 177 passengers to disembark, the evacuation taking three-and-a-half hours.

With a U.S. Coast Guard cutter and other vessels standing by, Kathleen’s 118 crewmen continued to run the pumps for 20 hours until 11 o’clock that night when it became apparent that she couldn’t last much longer. Two hours after they abandoned ship, she slid under, her final moments being captured in dramatic photographs that show her standing almost vertically in the water, her slender bow pointing skyward.

Top: Princess Kathleen in her death plunge; below, the end. —BC Archives

On the rocky shore, a fire had been built and passengers were served coffee and a light meal while willing hands wielded fire axes to slash a path through a half-mile of bush to a road. When it became apparent that Kathleen was going down, most of the crew joined those on the beach and watched in silence.

As she began her death plunge they “bowed their heads and wept”.

Survivors huddle on shore in bed sheets while awaiting rescue. —BC Archives

“She wasn't damaged so badly," complained Capt. Hughes. "She would have floated easily enough if we could have got tugs to help. We tried to back her off, without success. Then, by running her two engines in opposite directions, we tried to keep her stern up to the wind, but a 40-to-45-mile-hour nor-wester pushed her around sideways and that's what took her life.”

A marine reporter mournfully recalled: "Even when she returned from war service with only a streak of buff on her funnel to relieve the dull grey paint, she looked every inch a princess. And when she wore her sparkling white paint, gleaming brass and colourful flags as a cruise ship, she was a beautiful sight.”

Others noted that her grave in deadly Lynn Canal is within miles of two previous company fatalities: S.S. Islander struck an iceberg in 1901 and Princess Sophia swept her entire company of 343 Souls down with her after impaling herself on Vanderbilt Reef in October 1918.

Capt. O.J. Williams, manager of the coastal service, called Princess Kathleen “the finest ship in the fleet. She was also one of the most popular. And she was adaptable. She was a perfect ship for cruises, and could...operate as well as either a day or night boat on the Triangle Run.”

When divers determined that the lost liner’s bow was only 28 feet down, but her stern was in soft mud almost 200 feet below the surface, the CPR abandoned its former flagship to the underwriters, a total loss.

Eighteen months later, Kathleen remained virtually unmoved from her resting place, despite expectations of her being pulled into deeper water by winter storms.

When two young Juneau businessmen announced their intention to attempt recovery of her cargo, the underwriters allegedly threatened legal action, saying such operations would be too risky, hopeless, and, for reasons unstated, they hoped the Kathleen would slip beyond reach.

Granted full salvage rights by the Canadian Dept. of Transport, which had jurisdiction over the wreck despite its being in American waters, amateur divers Magnus Hansen and Wendell Johnson made 36 dives on the Kathleen and reported her to be “in excellent condition". In December, marine underwriters Lloyds of London signed a salvage contract with Capt. Ron Woodgate, representative of unnamed ‘American interests’ who intended to re-float the liner and convert her into a restaurant.