Editorially speaking…

John Milton Bryant (1887-1913), who’s acknowledged as “one of the first American barnstormers,” had acquired his aviator’s license only six months before his death. An inset on his headstone in the Los Angeles Odd Fellows Cemetery reads:

In Memoriam

August 6, 1913 – The first fatal airplane accident in Canada occurred when John M. Bryant, husband of Alys (Tiny) Bryant, was killed in the crash of his plane at Victoria.

He has been overshadowed by his wife’s exploits as the first woman to fly on the Pacific Coast and in Canada, feats which earned her membership in the Early Birds of America, meaning she’d solo piloted an aircraft prior to December 1, 1916. She also set an altitude record.

Alys McKey Bryant wasn’t the only woman attracted to aviation; here we see Julia Clark and her unnamed pilot. Other than their goggles they’re in their ordinary street clothes. —flickr.com

As one of three siblings growing up in Indiana, Alys (1880-1954) had shown an early bent for traditionally male pursuits by learning mechanics from her widowed father and dreaming of flight—in, of all things, “an electric-powered craft”.

Breaking horses on the family farm was also out of the ordinary for a teen-aged girl; at 17, she left home to attend university than began teaching home economics—a “female” avocation at last. Somewhere along the line she learned to drive a car and a motorcycle, definitely out of the ordinary for young women of the early 1910s.

But everything changed in 1912 when, aged 32, she saw her first plane as it made a cross-country flight. It inspired her to answer an advertisement placed by the Bennett Aero Co. of The Palms, Calif., for “a talented young lady to learn to fly for exhibition purposes”. Promised “the ultimate in excitement,” she signed on as a trainee with Bennett and his chief pilot, Johnny Bryant.

Things were casual in those pioneering days of flight. As noted, Bryant, wouldn’t get his own license until February of the following year but he was teaching others to fly; he accepted Alys as a student and trained her to be a flying performer, all in a matter of a few months.

Although unlicensed, Miss McKey achieved the distinction of being “the first female pilot on the West Coast” and gave her first professional exhibition as the Blossom Festival in Yakama, Wash, on May 2, 1913, followed by aerial performances at Portland, Oregon’s Rose Festival and the Seattle Potlatch Airshow. There, she set an altitude record—2900 feet—for women; in Vancouver, B.C., she thrilled, among the 1000s watching, the visiting British princes, Edward and George.

(One historian has suggested that the attractive and buxom Alys’s “daringly close-fitting coveralls” increased her public appeal to the men in her audience.)

A Vancouver Sun ad promoting the iron-nerved ‘aviatrice’ Alys McKey and the death-defying aviator Johnny Bryant. —Wikipedia

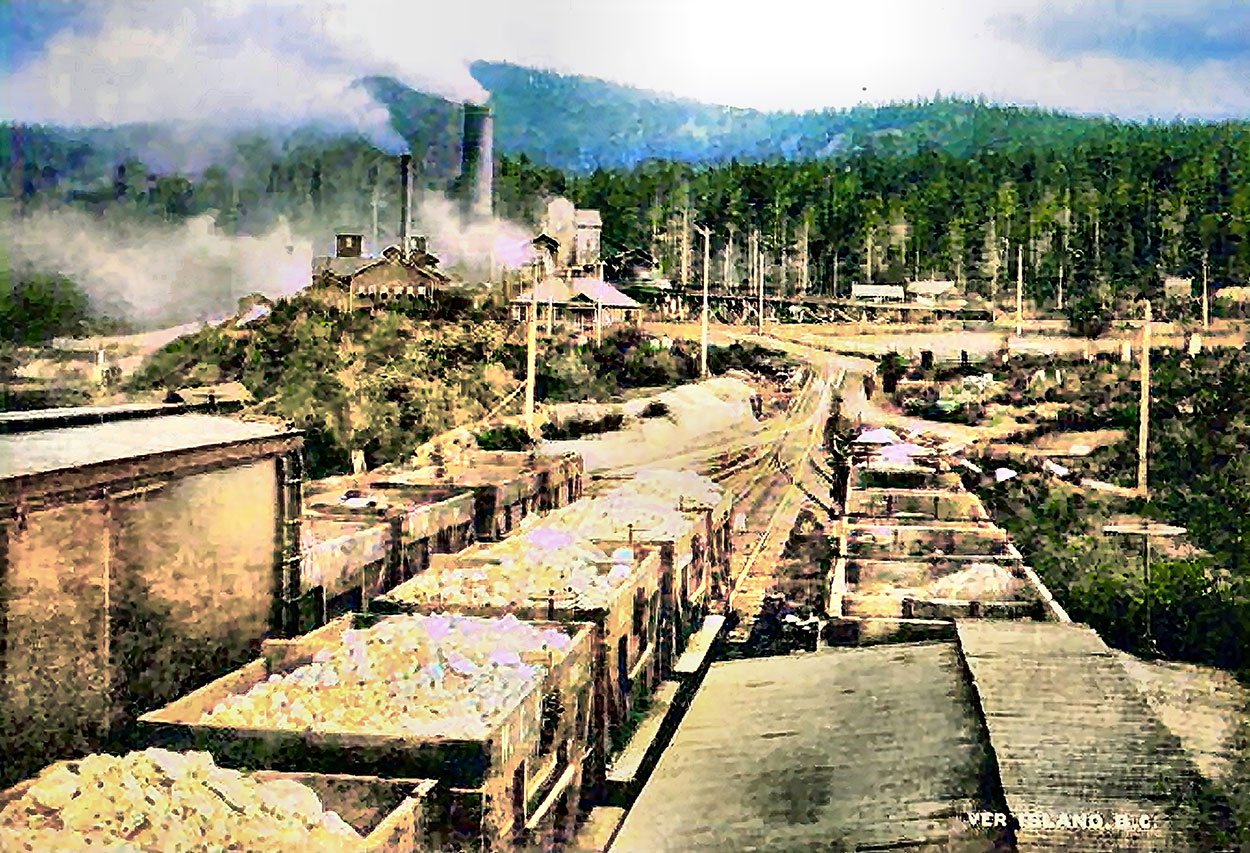

During the exhibition at Minoru Park, Richmond, B.C., she stole the show with “the clever manner in which she handled the plane,” by dipping, rolling, performing figure eights and “other evolutions of a like manner”.

She topped off the memorable day by marrying her tutor, friend and lover, Johnny Bryant.

Then they were off to Victoria for Carnival Week and, as it turned out, disaster. Years later, when recalling her own exhibition flight cut short by strong cross-winds, she described that flight in Victoria skies as the “roughest, toughest and most fearsome” she’d experienced to that date. She also said that she and Johnny would have lost their $1000 fee ($32,000 today) if they’d cancelled his flight and she admitted that they hadn’t thoroughly inspected their aircraft for damage from the Minoru Park incident.

The bulk of the Bryants’ fee, $700, went towards repairs to the Lee Dye building. With what was left she returned to California, buried her husband and, temporarily, hung up her goggles and scarf. Come July 1914, however, she was again airborne for the Seattle Potlatch Airshow where she told a reporter from the Seattle Star that she fully expected—even wanted—to die as had her husband, while at the control stick of an airplane.

He’d taught her everything she knew of “the aviation game” and she preferred instant death in a crash to “a minor accident that would leave one helpless, to live, or half live, for years, useless to the world”.

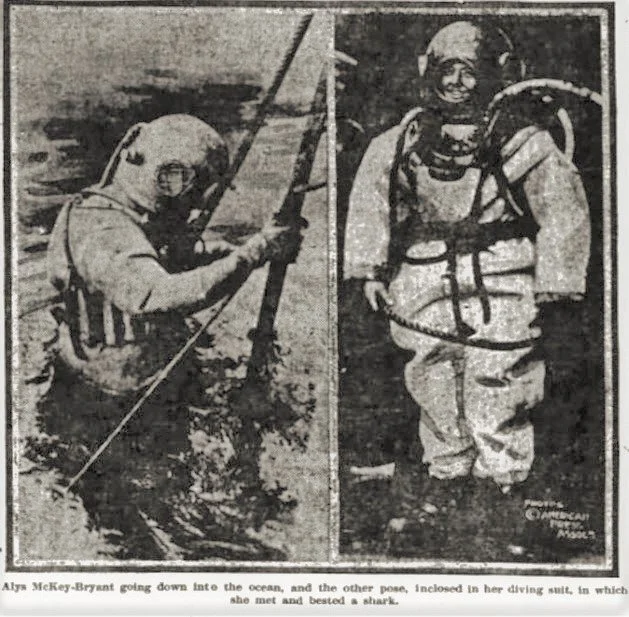

After teaching 100s of students to fly, and working in an aircraft plant during the Great War, she took up a new occupation—deep-sea diving. After learning the craft in Seattle she explored shipwrecks and removed obsolescent water pipes in the Pacific and Atlantic oceans, once, fending off a shark with an iron bar.

Alys made more news when she became a hard-hat diver. —WikiTree

Obviously made of iron herself, the remarkable Alys McKey Bryant married twice again, keeping in shape by boxing and strenuous physical exercise while promoting her own line of cosmetics.

She died in Washington, D.C., Sept. 6, 1974, aged 74.