10,000 Watched Canada’s First Fatal Air-Crash

Victoria entered the air age with a crash, 111 years ago.

During Carnival Week, August 1913, performing American aviator Johnny Milton Bryant plummeted to his death in downtown Victoria.

Stunt flying doesn’t always end well. —BC Archives

The Panama Canal had just opened, signalling increased maritime commerce for the length of the Pacific Coast, and the city was experiencing a real estate boom. B.C.’s capital was, in the words of a veteran newspaperman, “bursting at the seams”.

Hence Carnival Week, with activities ranging from a parade, a concert and numerous sporting events, to the stars of the show, a bi-plane and a gas-filled balloon.

The resulting tragedy would make Canadian aviation history.

* * * * *

But it wasn’t the only aviation history made that week. Days before, at Vancouver, on the morning of July 31st, California aviatrix Alys McKey Bryant, wife of the doomed flyer, had entered the record books “as the first woman to fly in Canada,” and Johnny had set a new altitude record of 5100 feet.

(Not everything went smoothly, however; while at Minoru Park, Bryant was angered to find a woman described as “very stout,” sitting in his pilot’s seat to have her photo taken. When he ordered her off the plane, she supported herself by holding and, it was later realized, straining the cables securing the right wings.)

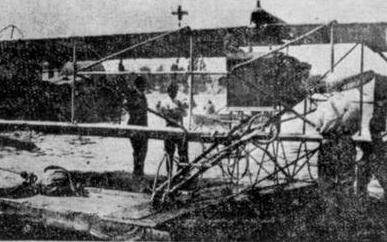

For an airfield during Carnival Week, the husband-wife duo used the Willows race track for their Curtiss amphibious pusher-type biplane (the first ‘seaplane’ to fly in B.C.).

“Like a great eagle," marvelled a Victoria Daily Times reporter, Miss McKey Bryant “made straight for the sun, whose light gleamed white on the canvas of the planes [wings], and rising, ever rising, turned towards the grand-stand where 1000s of eager faces, upward lifted, watched every sway of the arrow plane with bated breath.

“The roar of the engine was almost deafening, but coolly and with a sure-hand the aviatrist [sic] circled away from the Willows track and in the direction of the Uplands..."

The wind was gusting and uncertain that morning and Miss McKey had some difficulty in keeping control of her fragile craft which resembled the Wright brothers’ creation at Kittyhawk. Twice, she was seen to “rock...from side to side, the long planes skipping like the wings of a swallow in full flight”. Caught in turbulence, Miss McKey twice attempted to turn back towards the Willows track only to be “driven sideways”.

Alys McKey Bryant/Harrison ‘Tiny’ Bryant. —Find A Grave

It wasn't until she was over the city that she was able to make a sharp turn, when, at “fully a mile a minute [she] made back in the teeth of the breeze towards the field. Maintaining an altitude of a few 100 feet, Miss McKey soared over the track until she was over an adjoining field, when she “made a magnificent vol-plane into the enclosure, shut off her engine and canted along the ground for a score or so of yards before coming to rest plumb in the centre of the field”.

It was, all in all, a spectacular display of skill for the day, and Miss McKey’s feat was greeted with cheers. Minutes later, as she stepped to the ground, she was surrounded by well-wishers who surged from the grandstands to congratulate her and ask questions. Asked as to her problems in making a turn, she replied, “The conditions up there are worse today than I have ever been up in. The wind was very treacherous.”

Although a comparative newcomer to aviation, Miss McKey held the American altitude record for women.

She’d earned this distinction at Seattle when she flew to 3400 feet and it was understood that she would attempt to break her own record while in Victoria. The Curtiss bi-plane involved, noted a reporter, had a very powerful engine and was said to be extremely reliable.

This very machine would, in fact, make aviation history in Victoria—but certainly not of the kind that Miss McKey or anyone else had in mind on the morning of Aug. 5, 1913.

Victorian carnival-goers were blessed that week with not one flying machine but two, as the first gas-filled balloon ever to make its appearance in the provincial capital was also in town. For days, “a triple ring” of interested spectators had surrounded the contraption in the vacant lot behind the Empress Hotel, in anticipation of the moment its pilot cast off his line and took the “skyward soar for which the shining monster has being vainly waiting".

A vacant lot behind the Empress Hotel served as a landing and takeoff site for the California. —Author’s photo

Reason for the delay was the tardy arrival of the 20-horsepower engine which operated the winch controlling the balloon’s 2000-foot-long cable.

When its pilot did dare to make a trial flight with a couple of passengers, the winds which had plagued Miss McKey also played havoc with the “flagon- shaped sack," causing it to strain at its lines “in agitated action”. According to the pilot, the machine was safe in winds under 15 mph but he didn't care to carry passengers in anything stronger.

Built in Los Angeles the year previously, the balloon had been duly christened California with a bottle of champagne at the time of its maiden flight

Its most prominent feature was its body, a reporter describing the craft as a “big envelope, the sleek and glossy sides of which resemble the flanks of some well-groomed animal".

During the remainder of the carnival, the California and its unnamed pilot planned to accept two passengers at a time for a breathtaking ascent and aerial view of the city.

The same afternoon, more than 3,000 Victorians turned out at the Willows and the Gorge to watch rowing regattas and water sports played by the men of the American. British and Canadian navies. But, as in the morning, the real crowd-pleaser was the Curtiss bi-plane, to be flown this time by ‘Johnny’ Bryant, also an altitude record holder.

Despite the same gusting winds which had hampered Miss McKey (Mrs. Bryant), Bryant gave one of the longest flights of his tour "before the gaze of 1000s of eyes which were glued upon the swift-flying bi-plane". For a quarter of an hour, the 26-year-old Missourian thrilled his audience with his manoeuvres by climbing to an altitude of several 1000 feet then diving earthward until within a few 100 feet of the ground, when he made his “famous” roll and brought his audience to their feet with enthusiastic cheers.

Mr. Cool himself, the barnstorming aviator Johnny Milton Bryant. —Wikipedia

All of those watching were said to have been thrilled by his “complete mastery over the machine”. Performance done, Bryant made a perfect landing in the middle of the race track after making a final sweep over the stands while waving to his audience.

It was, according to the press, a brilliant performance.

The balloonist continued to have problems with the high winds, the California straining at her moorings. When two days passed with ground-level winds in excess of 15 mph, he wondered if it would be calmer once the California achieved her maximum altitude.

"Aero-planist” Bryant dashed this hope, however, when he reported the wind to be up to 35 mph at the 2000-foot level. The steadily increasing gusts even made it necessary to increase the weight of the balloon’s anchors behind the Empress Hotel.

The previous evening, a trial flight had been attempted but, due to the velocity of the wind, and the inadequate buoyancy of the gas, the “cumbrous envelope" had timidly ascended only to treetop level where it was caught by a northeasterly gust which promptly blew it off in that direction, then hung it up on the roof of the Church of Our Lord.

The Church of Our Lord where the California became entangled. —Chris06—Own work/Wikipedia

And there the balloon, its pilot and passenger remained until they were ignominiously hauled back to the Empress by cable.

Although he, too, was bedevilled by the winds, pilot Bryant refused to call it quits and, installing floats on his plane (another British Columbia first), braved the strong westerly to fly from Cadboro Bay to the Inner Harbour. Few of the 10,000 men women and children lining the causeway and adjoining streets, and holding on to their hats, had thought it possible that he’d fulfill his advertised flight when, from the east, had come the unmistakable drone of the Curtiss.

When the “bird-like” machine, with its white floats, began to circle overhead, all cheered the aviator’s courage.

“Soon the throng burst into cheering that swelled greater and greater, and from street to street, and, as if the aviator heard it, he waved his hand." For almost 10 minutes Bryant flew at at a height of nearly 1,000 feet, his airplane rocking like a cradle, and “great gasps of relief would go up from the throng every time the frail aerial vessel righted herself.

“In that wind the flight was dangerous, almost to foolhardiness, but the manner in which the aviator banked at the corners and headed off towards the wind showed that to the master pilot there was less danger than appeared to the onlookers...”

Completing his flight with a flourish, Bryant whirled downward in a series of circles to 500 feet then cut his engine and glided the remaining distance to the surface of the harbour. Moments later, as its floats creamed through the waves, the Curtis ghosted to the harbour entrance, turned, and effortlessly skimmed the distance to the Grand Trunk Pacific dock.

Upon stepping ashore, Bryant casually admitted that the three-mile flight from Cadoro Bay had taken all of 20 minutes as the Curtiss had encountered strong headwinds at the mouth of the bay—so strong, that, for five full minutes, he’d “stood still in mid-air, unable to move forward, the great propeller thrashing the air futilely". He’d then made a forced landing after narrowly avoiding one of the islets at the head of the bay before trying for a second time.

Immediately upon the ‘hydroplane’ being secured alongside the dock, the crowd surged forward for a closer look at the wonderful craft and warmly received the announcement that Bryant would make another flight at 5:00.

Bryant’s plane in the Inner Harbour as he prepares for takeoff on his fatal flight. —BC Archives

Almost on schedule, Bryant boarded his plane, since moved to the Marine and Fisheries wharf, and, engine turning smoothly, headed out into the harbour. Immediately becoming airborne, he circled and headed back towards the city. By the time he was over the business centre he was thought to be at the 800-foot level.

Moments later, as the audience of thousands lining the Inner Harbour watched intently, the Curtis continued northeastward to Fort Street then Blanshard where Bryant began to make his turn.

But, as he passed over City Hall, the plane ‘took a sudden swoop downward till the elevation would be between 100 and 200 feet. As it came down the right [wings] seemed to crumple up and Bryant was seen to be stooping over, apparently in the effort to right something about the steering gear."

The Curtiss soared over the old Market Square and fire hall, rapidly losing altitude, crossed Government Street and “dropped almost vertically to the top of the Lee Dye building” at the corner of Cormorant Street and Theatre Alley. Bryant had been in the air for less than five minutes.

Victoria’s Chinatown entered the aviation history books in August 1913 when Johnny Bryant crashed into the roof of the Lee Dye building. —Author’s photo

Almost from the moment of his takeoff, those watching had been sure of impending disaster. Obviously unable to gain the satisfactory altitude, Bryant had faltered momentarily then regained control and entered his turn as a “cry of dismay went up and [none of those watching from the harbour] drew breath for the few seconds that really elapsed until he ‘d fallen on top of the building”.

Instantly, all began running towards Chinatown, Fisgard Street being transformed into a “solid mass of people".

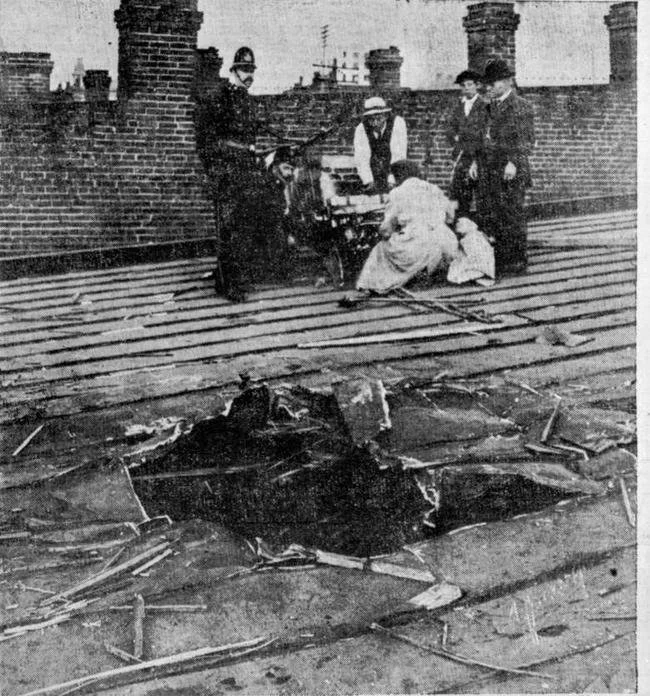

Well ahead of the rush were City Detective Heather, Motor Constable Foster and Constable McLellan, who’d started for Theatre Alley at a run as soon as they realized that Bryant was about to crash. Reaching the top of the Lee Dye Building by means of a ladder from an adjoining roof, they found themselves a second or two behind a Mr. Ferrin, who’d watched the tragedy unfold from Cormorant Street.

A newspaper showing the hole in the roof of the Lee Dye building; in the background, Victoria police examine the engine of Bryant’s ill-fated biplane. —BC Archives

Bryant was lying on his side, beneath the crumpled wreckage of his plane. Buried in canvas, wood and wires, he was barely breathing but alive, although the policemen realized that there was nothing they could do for him. When, minutes later, Dr. George Hall was lifted to the roof by aerial ladder (the first fire truck having been delayed by the shoving mass of people in the street), Bryant was dead.

The flyer had sustained a broken neck, a broken back, a fractured skull and both legs were broken—yet, amazingly, but for a cut above one eye, there was no obvious sign of injury.

Tenderly removed from the wreckage, Bryant was wrapped in a sheet and lowered to the street. There, the crowd, which had by this time reached the scene, scrambled for a glimpse of the body, the police having to fight their way through them to the ambulance. When police then began to lower the wreckage to the street, a near-riot ensued as men and women fought for souvenirs of the wreckage, prompting a disgusted reporter to remark, “a more unseemly sight could not be imagined than was presented by the ghouls”.

Among those who’d witnessed the crash was Mrs. Bryant, who’d known before the others that her husband was in trouble.

She was running towards Cormorant Street, almost hysterical, when Police Chief John Langley overtook her in his car and picked her up. When he informed her that Bryant was dead, she collapsed and had to be escorted to the police station, where she was attended to by Dr. Hall.

It was then learned that J.W. Bennett, owner of the lost plane, and the Bryants’ manager, had warned Bryant against flying that day; not only because of the wind conditions, but because of the injury the aircraft had sustained the week before. (An examination of the wreckage found that some of the braces for the right wings had been stretched to the breaking point—a result of the crash or because the “stout lady” pulled on them at Minoru Park?)

Bryant had insisted on going up, however, saying that he didn't wish to disappoint the people (or lose his fee).

Bennett had been waiting for him at the British American Paint works on Laurel Point, where he expected him to land. When Bryant had taken off, Bennett had had to move around a building for a better view, by which time the plane had crashed.

Bryant, sighed his manager, had been above the ordinary run of professional aviator, and “in every way a man of high character". It was through Bennett that Bryant had met Miss McKey, then a flying student. They’d been married only nine weeks.

At the inquest Bennett testified that he thought the plane’s steering post buckled and Bryant, while trying to reach the control cable, grabbed the wire holding the strut between the wings, causing it to collapse and throw his plane out of control.