Seeking Justice – Bea Zucco’s Amazing Crusade

Years ago, when I was still writing the Chronicles in the Cowichan Valley Citizen, I received a complaint from a young woman who accused me of writing only about male pioneers.

She hadn’t been paying attention. I was able to reel off a list of women whose stories I’d told from my days of writing for the Colonist to that point in time in the Citizen. To name just a few, locally, provincially and nationally:

—Annie Duncan

—Clara Gravenor

—Johanna Maguire

—Elizabeth Sea

—Minnie Paterson

—Nellie Cashman

—Lillian Alling

—Anna Mae Ullman

—Nellie McClung

—Laura Secord

—Edith Cavell

—And numerous others

There were more but I’m not going to dig for them now. Yes, by far, my articles were male-oriented because, folks, the colonial British Columbia frontier was, for the first decades, predominately a man’s world.

Which isn’t to say I couldn’t have tried harder to be more inclusive. But when working to deadline, as I almost always was doing in those days (and still do), I followed the line of least resistance. So men’s adventures, achievements, conflicts and failures it was...

But her complaint did give me pause for thought which, in my usual roundabout way, brings us to this week’s Chronicle. For years now, and I do mean years, I’ve had a book on my desk that contains an article about a truly amazing woman who so impressed me that I’ve wanted to write about her.

But there’s always something to do and I’d need the publisher’s permission to make use of the firsthand content so I kept putting it off and off and off. The book I’m referring to is Volume 13 of Boundary History, published by the Boundary Historical Society boundaryhistorical@gmail.com.

Well, last week I bit the bullet and emailed them, asking for permission. Talk about service!

Within half an hour I had a response from Doreen Sorensen, Secretary, saying she’d pass my request on to her board of directors. Next day, I had their approval. All they asked in return is that I acknowledge the BHS which, as you can see, I’m doing here.

So who is the heroine who so impressed me that I’ve kept her at my elbow all this time?

—Family photo courtesy of the Boundary Historical Society

Hands up, those of you who recognize Bea Zucco. To quote the BHS, “From miner’s wife and mother in the bush to champion on the steps of the provincial legislature, and more, Bea...travelled a unique path. Her story is an inspiration.”

Quite simply, her husband, a miner, became terminally ill with the dreaded occupational hazard and ‘widow-maker,’ silicosis. But there was no Workmen’s Compensation pension, no government interest, just the old story of “too bad, so bad...”

Mrs. Zucco, like 100s of other miners’ widows with young children to care for, was on her own. She resolved to fight to have the disease officially recognized as a workplace hazard and threat to workers’ health. Her nine-year-long struggle, during which time she, too, contracted tuberculosis, took her all the way to the Provincial Legislature.

That’s the Bea Zucco I want to tell you about. A peoples’ champion who has received too little recognition. As I’ve long argued, we Canadians just don’t seem to honour our heroes, male or female. Ironically, in the few cases where we have done so, we’re now hellbent on tearing down their statues and their reputations.

But no editorializing; just the story of Bea Zucco who, unable to help her own husband, set out to help her young family and, ultimately, 1000s of others in the same dire circumstances.

What follows is, for the most part, in Bea’s own words. I’ve kept editing to the absolute minimum and offer a summary at the end...

* * * * *

If something good comes, I enjoy it to the fullest, for I know it cannot last forever. If something bad comes, I live through it, for I know it will pass.

I was born in 1922 in Nelson, B.C., but my family moved to Grand Fork when I was two years old. My Mother died when I was five and I was raised by my father, my Granny and friends.

When I was in Grade 6 my Father moved my sister, Margaret and me up the North Fork [the Granby River, then considered to be the North Fork of the Kettle River] where I finished school, Grade 8, at the Beaver Creek School. My father was ill. It was still Depression time and we were not able to go any further in school.

When I had just turned seventeen, in January 1940, I married a neighbour, Jack Zucco.

He was born in Spokane, Washington, in 1911. The first years of his life were spent in Phoenix [B.C.] but when he was quite young his parents moved to a farm 20 kilometres up the North Fork. He also went to the Beaver Creek School to Grade 8. He went to work at a very early age, first for Bob Simpson and then when he was old enough (probably 15 or 16) he went to work underground at the Union Mine. He worked in various mines in the Kootenays—the Durango, the Kootenay Girl.

Within the year of our marriage we moved to Bralorne and then on to the Red Rose mine at Hazelton. It was quite an experience for a girl of eighteen. We lived in tents with a bed made of fir boughs, about 10 inches long and stacked with the soft end up. The bed had to be remade when a sunny day came, which was very seldom.

My days were filled helping the camp cook. He had to cook everything on a 45-gallon stove with a flat top. I had a very tiny cook stove with a small oven, but everyday I made a cake for the crew of about 15 or 20 men. To show their gratitude, as each one went to town they would try to outdo each other by buying a bigger and better box of chocolates. It was during the war and things were rationed. Since I had more chocolates than I wanted they were passed around at the supper table.

I became pregnant with my first child.

At this time we moved up to the top of the mountain, a mile above [the] timberline into a very small cabin with ice still on the inside of the boards. I still had my little stove which was quickly put to good use drying out the cabin. We had only scraps of lumber for wood as there were no trees. We were happy to see snow arrive as the only water was brought up in two barrels on horseback. Each trip probably took three hours and the water had to service the cookhouse and about 15 men and myself.

Our little cabin was about 10’ by 12’ and held a REAL bed, my little stove, a small table and (blasting) powder boxes for chairs. I had a few shelves put up and kept chocolate bars, shaving cream, cigarettes and small items that the men night need.

My entertainment in this camp was helping the cook. The new cook loved to drink all the extract flavouring as there was no liquor allowed in camp. Consequently, he would get drunk quite often and would order me around, but he did teach me to roast meat and to make pies. Eventually my husband, who was the foreman, cancelled all flavouring coming into the cookhouse. Any cakes were then made without any flavourings.

One incident I won’t forget was the flying outhouse.

Because it was very windy, all the buildings were held down with cables tied onto logs buried in the ground, all except the outhouse. The men would wait one by one in a line up after dinner. As one man came in the other would go out. One time as the door was opened the man waiting saw the outhouse flying over the hill. Until a new one was built they all had to use the mine!

At this time I was getting close to the end of my pregnancy and the first aid man was worried that I would have the baby early. I had to go to Hazelton. The new baby was two weeks overdue.

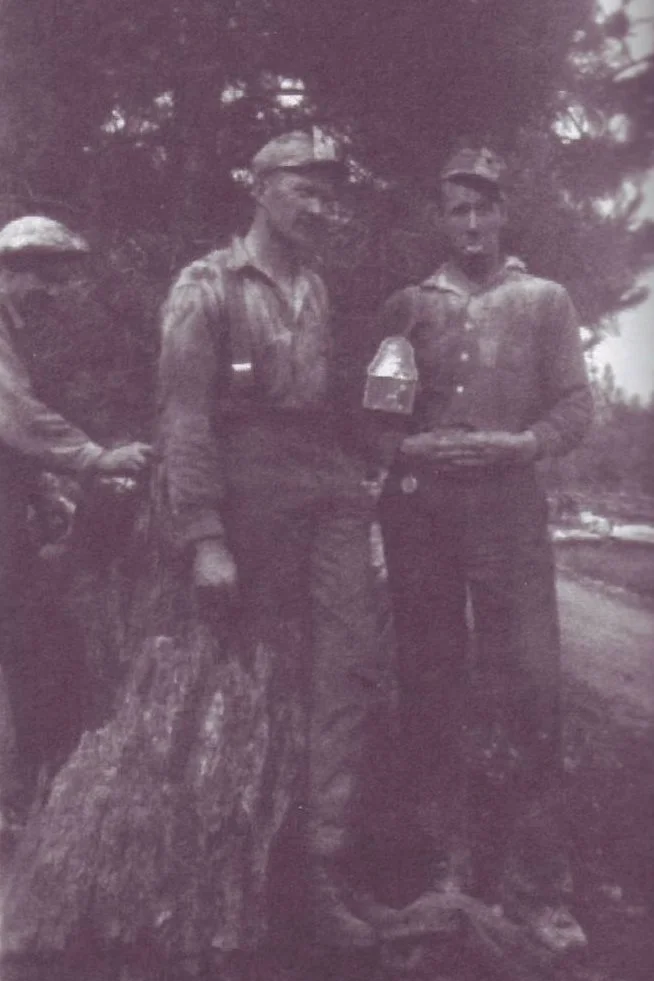

Hard rock miner Jack Zucco, right, and the mountaintop Red Rose Mine. —Boundary Historical Society

We lived at the Red Rose Mine until 1944 and then we were moved to Trail. The mine at Hazelton produced tungsten and it was no longer needed for the war effort. We moved from Trail to Grand Forks where we farmed for a few years, then to the Fairiew Mine at Oliver and then on to the H.B. Mine at Salmo. By this time we also had a son, Johnny, and I was pregnant with my third child, Sylvia.

We were back living in tents, but in June we moved into a beautiful little company house in Salmo which I designed.

In September 1949 Sylvia was born in Trail Hospital. It was about this time Jack came down with a bad cold. I came home with the new baby and life was wonderful. We had a beautiful new home. We bought our first furniture, a chesterfield and a record player with one record—the Mills Brothers. I’m sure we wore out a needle playing that record.

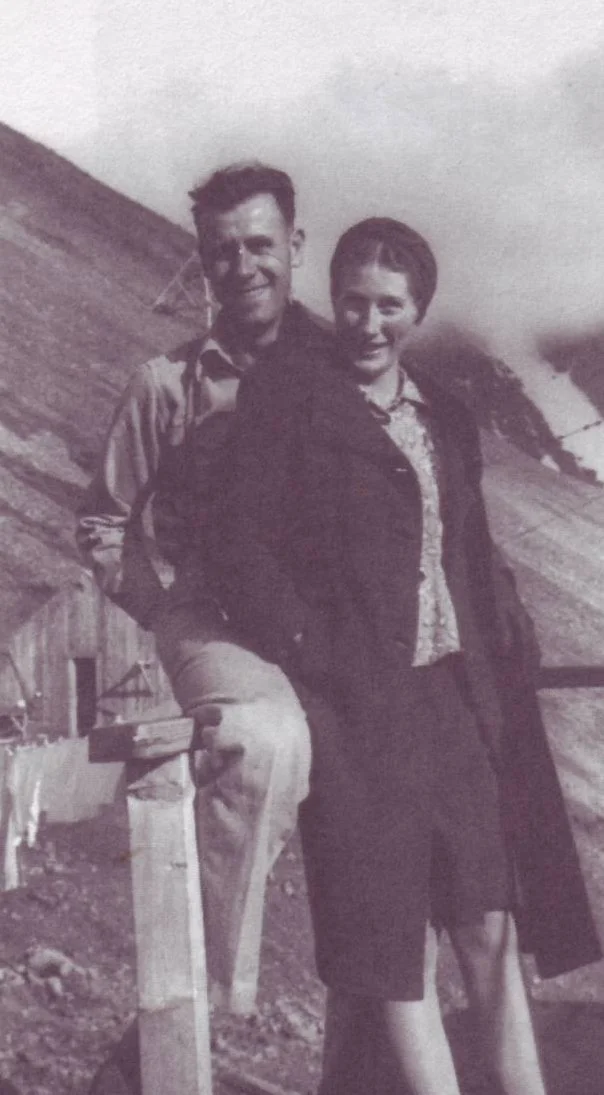

Jack and Bea in happier days. —Boundary Historical Society

Six weeks went by. My husband was getting sicker. I finally talked him into going to see a doctor in Salmo. The doctor sent him to Nelson and they put him in the hospital. The next day I went to see him. It was then the doctor told me he had tuberculosis.

My whole world was shattered. I remember driving home from Nelson to Salmo, crying all the way.

Jack was sent to Tranquille [B.C.’s tuberculosis sanitarium, 1907-83] and I had to move from the Company house. I had no place to go. My daughter Margaret was left in Salmo with the Albert Best family as she was going to school. Johnny was sent to Grand Forks to stay with my sister, Marg Bryant, and Sylvia, my beautiful new baby, was left with John and Olwyn McMynn at the mine. I went to Kamloops to be near my husband. I went to work at Tranquille

In 1952 I was called into the doctor’s office where I was told they expected my husband to live only another month or two. I had been corresponding with Dr. Goresky in Castlegar who had been helping people to heal themselves through psychology. I took my husband out of Tranquille on a stretcher and took him to Castlegar where we moved into a basement suite. The people from the mine at Salmo had moved our furniture and filled the fridge with food.

After a few months my husband had gained weight, was up walking and I was so sure he was getting better. A trip to Nelson for X-rays dashed all my hopes. Dr. Morrison told me the TB would not heal because of the silicosis in his lungs. Unfortunately, I couldn’t get it in writing. (The silica dust, common in hard rock mines, causes damage to the lungs. A pension is provided for patients with silicosis, but not for those with tuberculosis.)

We moved into a house in Kinnaird and by this time John McMynn had convinced Cominco to pay out Jack’s life insurance, over $2000. With that and some help from my father we managed. His father bought the place in Kinnaird. Now I had all three children living with us. It proved very hard on the children. They were shunned at school because their father had TB.

I became pregnant with my fourth child. Dr. Goresky told me my husband would live as long as I looked after him and that he could even outlive me. I had to make a very big decision. Him or the children. Jack was put into Pearson Hospital in Vancouver.

In August, 1952, my daughter, Dede, was born. In the hospital they decided to give me a blood transfusion to help me get back on my feet. Then a year later the public health nurse gave me another TB test and it was discovered I had TB also. Up until this time I had always had a negative patch test In those days the doctors did not believe anything could be passed from one person to another in the blood.

The family was separated once again. The children were put into other people’s homes and I was sent to Pearson Hospital where I spent a few months. When my husband had first gone into Tranquille and I was working there, I watched fear take over the patients.

Now I was living in the midst of this fear, but was determined to overcome it.

After a few months in the sanitarium, the doctors wanted to operate on my lungs and cut out the TB. Since I was still “negative” and could not pass the disease on, I refused the operation and signed myself out. I had very little money and my friends thought I was crazy.

I spent a few weeks in a cheap boardinghouse to gain my strength back. Then I used a diamond ring to put a down payment on a car. I talked some cosmetics people into trusting me with a load of cosmetics and left for the Interior. It was one of my unforgettable trips. The very first day I got into Aldergrove where I checked into a motel.

In the morning I managed to sell the lady who had the motel enough cosmetics to cover the price of the room. Then I headed for Hope where I sold a lady at a beauty parlour some stock. Then on to Manning Park where I spent the weekend in a bunkhouse—cheap rent. I sold all the girls who were working there more cosmetics.

On Monday I drove to Princeton, rented a motel for a week, bought a few groceries and spent every spare moment when I wasn’t selling cosmetics, practising Dr. Goresky’s theory. To make a long story short—in six months I returned to Vancouver.

My husband insisted I have an X-ray and I was cured.

The only other treatment I took was from a chiropractor, Steve Liptak. He told me to get out and climb mountains, get lots of exercise, because I was sneezing a lot. He said that was my body’s way of getting rid of everything. I studied Dr, Goresky’s theory religiously. I guess I wanted to prove that my decision in bringing my husband to Castlegar had been the right one. I should have taken him to Steve, also.

Then I moved to New Westminster. After several attempts to get some written statements from the doctors that Jack had silicosis, I took him out of the San and drove him to Bellingham. There he was X-rayed and I got a letter from that doctor saying that he indeed had silicosis and that it was making it impossible for the TB to heal.

I took this information to the Workmen’s Compensation Board, but they ignored it. That was when I decided to take my children and sit on the steps of the Compensation Board office. We got lots of media coverage, but all they promised was a commission. When I received a letter months later turning down my husband’s request for a silicosis pension, I then took my children to Victoria where we sat on the Parliament steps for a day.

Lots more media overage and another promised commission. Then another letter turning down the pension.

In the meantime we were evicted from one house, then the second eviction. I then decided to move the children back to the Interior. I went to a car dealership in Vancouver and convinced them to loan me a car. I put a big sign on the top and drove to many mining camps where I gave talks. The men and the Union donated enough money to keep me going and to hire the Union lawyer, John Stanton.

I talked to every provincial politician and wrote letters, but it was a waste of paper, stamps and time.

Then there was an election coming up and I went to Victoria and sat on the steps of the Legislature for ten days. I slept in my car the first couple of nights. Then a mining engineer whom we had met at the Red Rose Mine invited me to stay in their house at night. What wonderful people! When I left Victoria they gave me an envelope to open on the ferry. It was a lovely note and $50. A fortune!

I was living from hand to mouth, but in my spare time I was selling a cleaner and if I could make a sale two or three times a day I could get by for that day. I was always selling something: cosmetics, wonder brushes, books, pots and pans, cleaners, whatever. There was probably another commission. I lost track. I spent a lot of time cornering politicians. I heard they were giving a speech somewhere, I would be there.

In 1957 I had a bad case of burn-out and I went by boat to Kitimat. I was selling silverware then, but the weather was dreadful. I had no car and the bus service was terrible. Fortunately, I’d picked up a B license somewhere along the way and knew the RCMP Sergeant. After a couple of very difficult weeks I got a job driving cab. It was quite an experience.

I came back to Vancouver because my husband was very ill.

He died on April 2, 1958 and by this time the doctor in charge at the San was very helpful. I phoned the lawyer and he protected the autopsy so the “problem” couldn’t be buried.

Since it was going to be several days or weeks before I would know the outcome, after the funeral I packed up what few belongings I had into an old car. It had poor brakes and I had to go down all hills in low gear. It took me two days to drive from Vancouver to Castlegar. I was worn out, both physically and emotionally.

After a week or two I had a call from Simma Holt, a Vancouver Sun reporter, who had taken a real interest in the case and remained a friend for years. They had proven the silicosis and could I come to Vancouver to collect the pension? I had no money and very little energy, so Simma sent me the money for a bus ticket.

That was 36 years ago and after the children were grown I started the Argosheen [Carpet Cleaning Shampoo] business. All my previous experience in selling was put to good use when I found a wonderful product that we buy direct from the manufacturer.

Today my daughter, Sylvia, looks after the business and I enjoy a lifestyle I have always dreamed of—a little farm, chickens, a garden a faithful dog and a few cats. I am so grateful to have been able to return to Grand Forks and the quiet life.

* * * * *

This case received wide spread publicity at the time. Quote from the Vancouver Sun, April 24 1958, “Make Amends to Mrs. Zucco”.

“Nothing less than retroactive pension award will satisfy simple justice in the Zucco case. The dead miner should have had a pension from the Workmen’s Compensation Board during his disabled lifetime. His widow ought to be reimbursed for the sum foregone and pensioned for the future. If the law doesn’t allow for this course, then the law ought to be changed.

“No matter how generous the settlement, Mrs. Bea Zucco has earned every penny in her courageous fight to prove that her husband suffered from compensable silicosis. A pathologist has now established that the WCB made a tragic mistake—certainly in good faith—in rejecting the claim... The speed with which the Board makes amends will be one measure of the sincerity of its apology.

“The public’s admiration and sympathy went out to Mrs. Zucco for her determined struggle in what seemed to be a lost cause.

“She can’t be compensated in money for years of grief and misery. But she may derive some satisfaction from knowing that her fellow citizens regard her as a woman of heroic character.”

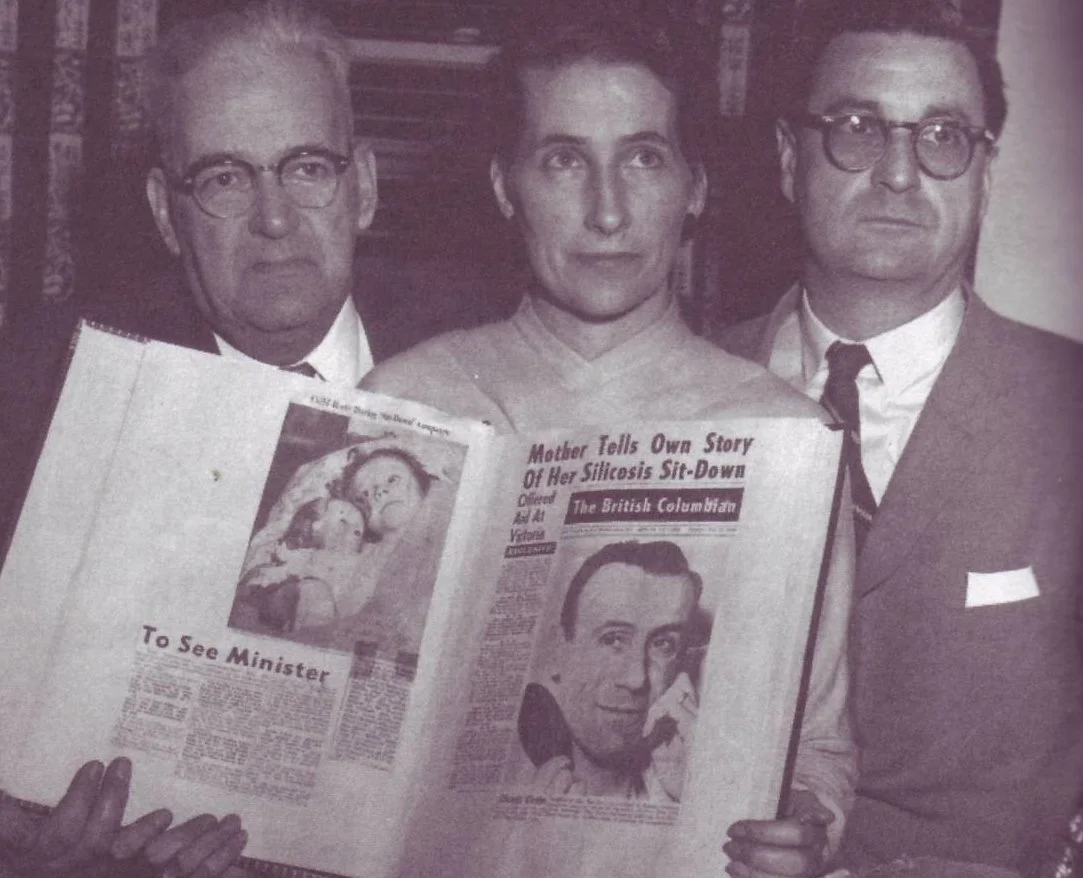

John Stanton, a pioneer labour lawyer, handled the Zucco case against the WCB at the request of Les Walker, a mine mill officer who was also suffering from silicosis. Stanton writes of this case in his book, Never Say Die, 1987, Steel Rail Publishing:

“The case had taken nine years and included the professional opinion of many doctors. Sixteen had confirmed a diagnosis of silicosis; only seven had not.

Les Walker, Bea Zucco and labour lawyer John Stanton show newspaper clippings of Bea’s crusade from her scrapbook.—Boundary Historical Society

“Bea Zucco and her children received the benefits to which they were entitled under the Act. It was a long-overdue debt the mining industry owed to Jack Zucco, whose youth had been sacrificed to enrich the industry. Money alone could never compensate the Zucco family. Jack not only suffered the physical torments of the disease but experienced the anguish of knowing that he was dying without being able to provide for his family.”

Boundary History Editor’s Note: Bea Zucco, having faced incredible hardships with a dying husband and with four small children to care for while she herself had contracted TB, had finally been vindicated. It was a victory not only for the Zucco family, but for others suffering from silicosis.

“It became a benchmark case and had immediate repercussions to amend the Workmen’s Compensation Act to ensure there were no more cases where someone had to die to prove his rights to a pension. She opened the way with grace, courage, determination and drive and all without bitterness.”

* * * * *

In June 2018 an obituary in the Grand Forks Gazette reported that Bea Zucco had passed away, peacefully, with her family at her side.

Predeceased by her husband Jack and son-in-law Terry Kinsella, she was survived by daughters Margaret, Sylvea and Dede (Jay), and son John (Carol).

“Mom wore many hats as a sales person,” the family noted, “starting with her home made cheese when she lived up the North Fork. She also sold pots and pans, world book [encyclopedias], jewelry, etc...”

The obituary went on to list the other products that Bea, the master sales person born of necessity and natural ability, had promoted over the years.

As for Bea’s lonely, years-long crusade ‘seeking justice,’ “Mom was an advocate for families who had lost loved ones to silicosis and TB from working in the mines. She fought the Government and WCB and finally won her fight seven [sic] years later. She was a very strong and determined lady who fought for what was right...”

Well-earned retirement had suited Bea well.

Bea poses with broom before her rustic cabin during her contented retirement. —Boundary Historical Society

She had her small farm where she planted large gardens every year, relished having her family and friends about her, going to the casino, and travelling, including a trip to India, several to Australia to visit daughter Dede and family, to Tasmania and Fiji, and one around the world in 1973.

Ever the adventurer, while Down Under, age 80, she climbed the Sydney Harbour bridge and walked around famous Ayers Rock. She was 89 when she paid her last visit to Australia.

There you have it.

That’s the lady at my elbow I’ve wanted to write about all these years. My thanks to the Boundary Historical Society for allowing me to share Bea’s incredible story with Chronicles readers.

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.