Sewell Moody: Man of Prophecy

“Sale of the Burrard’s Inlet mill—the sawmill owned by J.O. Smith was sold on Thursday by his creditor’s assignees. It was purchased by Mr. Moody for the sum of $6900.”

This brief business notice of 1869 announced the start of a remarkable career in pioneer provincial commerce, that of far-sighted and highly respected American financier Sewell Prescott Moody whose career was cut short by disaster.

A tragedy made all the more poignant by Moody’s message from the beyond the grave.

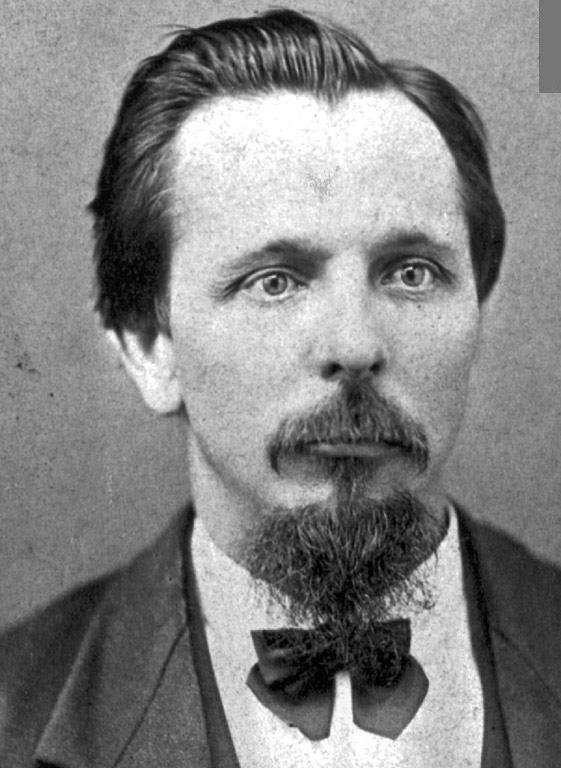

Hartland, Maine businessman Sewell Prescott Moody who, in just 14 years, set frontier British Columbia on the road to industrialization. — PD-US, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10903026

Moody left a legacy that’s with us today. He’d been among the first—and among the few—to recognize the future of ‘Burrard’s Inlet’ when it was just a rain forest.

In those days, when New Westminster was the capital of the mainland colony of British Columbia, and Victoria the capital of the Crown Colony of Vancouver Island as well as the commercial leader of the entire Pacific Northwest, the brash young Yankee’s predictions were greeted with open scorn.

Yet, within 20 years, the future became apparent even to the scoffers and, although Moody didn’t live to see his dream come true, his imprint on a young province resounds to this day.

When Captain George Vancouver had poked about ‘Burrard’s Channel’ in the late 18th century, he learned to his disappointment that the Spanish had beaten him twice, the second time as recently as days before. Notwithstanding this, he proceeded to name many of the predominating geographical features and christened the inlet for friend and former shipmate Captain (later Admiral) Sir Harry Burrard. He described the fjord-like waterway thus:

“From Point Gray we proceeded first up the eastern branch of the sound where, about a league from its entrance, we passed to the northward of an island which nearly terminated its extent, forming a passage from 10 to seven fathoms deep, not more than a cable’s length in width.

“The island lying exactly across the channel, appeared to form a similar passage to the south of it, with a smaller island lying before it.

“From these islands, the channel, in width about half a mile, continued in direction about east. Here we were met by about 50 Indians [sic], in their canoes, who conducted themselves with the greatest decorum and civility, presenting us with several fish cooked, and undressed, of the sort already mentioned as resembling smelt.”

With HMS Discovery’s departure the inlet returned to being the domain of its inhabitants, the Squamish, Musqueam and Tsleil-waututh tribes. Not until the mad rush up the Fraser River in search of gold, just over half a century after, did the dominating forest attract the fleeting attentions of passersby.

Even the Yorkshire potter, John Morton, who became its first settler, tried his luck in the gold fields before becoming interested in reports of clay deposits near Coal Harbour.

Undaunted upon discovering that the clay was actually sandstone, Morton decided to homestead and, with fellow ‘49ers Bill Hailstone and Sam Brighouse who’d accompanied him up the Fraser, Morton preempted 500 acres in what’s now Vancouver’s highly esteemed West End.

Alas, their struggle against the wilderness failed and the partners had to move on in search of wages.

For a time they were able to rent their rancherie until someone burned it down.

It remained for two entrepreneurs named Hicks and Baker to point the way in 1862 when they salvaged the power plant from a wrecked steamboat and set up a tiny sawmill on the North Shore. When, finally the struggling lumbermen got going they cut an encouraging 10,000 feet of lumber on their first day of operation.

Unfortunately, their first day of operation was also their last as their creditors foreclosed.

Although few seemed to realize it at the time, Hicks and Baker had attempted to harvest one of the richest stands of timber in the world: a seemingly-limitless jungle of fir, cedar, hemlock and pine that would ultimately sire a metropolis.

That same year, T.W. Graham and Company of New Westminster gambled that they’d succeed where Hicks and Baker had failed, and took a lease of 300 acres on the North Shore. Graham appears to have enjoyed greater operating capital than had his predecessors as the new company soon erected a water-powered sawmill and named its little settlement Pioneer Mills.

When, within months, the sternwheel steamer Flying Dutchman loaded the first cargo of 500,000 board feet, the great logging industry was on—almost.

However, Graham and associates (although they were cutting 40,000 feet of lumber daily) also failed and sold out to New Westminster grocer John Smith who set a record by shipping an amazing 278.000 feet of lumber and 16,000 pickets in a single cargo to Australia.

But with his subsequent failure, S.F. Moody & Company became the fourth venture to try for the golden ring on Burrard Inlet’s North Shore.

It’s said that “Sue” Moody, who’d become involved in the infant logging business in B.C. by hauling rafts of lumber from Burrard Inlet to Victoria, had crossed the U.S. continent in a covered wagon with his family when he was a teenager.

Arriving in B.C. in 1861, he worked as a timber cruiser and estimator before partnering with Moses Ireland who’d made a modest stake in the Cariboo diggings.

According to Ireland, his $2000 and Moody’s $600 allowed their company to succeed modestly by importing cattle and general supplies until Moody’s family background in lumber in Maine and experience of rafting logs to Victoria gave him the idea of exploiting the forests of the lower Mainland.

He, Ireland, Joshua A.R. Homer and Capt. James Van Bramer joined to build a steam sawmill in the Royal City.

Their start was anything but auspicious—when the first vessel to load for an export market grounded on a Fraser River sandbar and was stranded for six weeks, other ship masters were frightened off. So Sewell and company turned their eyes to Burrard Inlet. A second, successful attempt to purchase Graham’s Pioneer Mills at a bankruptcy auction enabled the partners to resume production in February 1865 and, to again quote the Dictionary of Canadian Biography:

“Though greatly handicapped by the lack of marketing information and [currency] exchange facilities, Moody slowly built up the first substantial lumber export business from the British Columbia mainland, and sent shipments to California, Hawaii, Peru, China, Australia, New Zealand and Great Britain.”

(The syndicate also invested in coal seams in Coal Harbour and English Bay in 1865 but nothing came of their British Columbia Coal Mining Company.)

The sawmilling Moody & Company also got off to a rocky start (literally) when their scow, the Matilda, stranded off Victoria and, with her cargo, became a total loss. Declared the Colonist: “Much sympathy is expressed for Mr. Moody...who has only recently built the mills [sic], and was about to commence operations.”

Despite this setback, with buyers in Victoria, Nanaimo and the Royal City, Moody, Nelson & Company (as it was now known) proceeded with plans to build a worldwide network of markets. Moody visualized a steady stream of ships calling at Burrard Inlet to load British Columbia lumber for ports of all nations.

Almost immediately, he succeeded where his predecessors had failed—and put Burrard Inlet on the map.

But not without another hiccup. By December 1873, the company, now known as Moody, Dietz and Nelson, had upgraded from water power to steam and expanded—only to lose it all in a disastrous fire. However, with the steam plant of the decommissioned Royal Navy gunboat HMS Sparrowhawk, the company was soon cutting 112,000 feet per 24 hours.

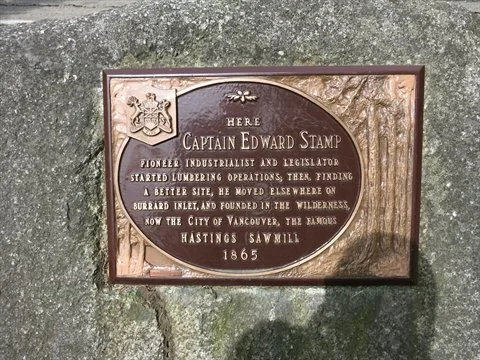

Another pioneer to see the potential of this region was Capt. Edward Stamp, founder of Vancouver Island’s first sawmill at Alberni. Upon personally examining the south shore of Burrard Inlet, Stamp returned to England to raise the necessary capital to form his British Columbia and Vancouver Island Spar, Lumber and Sawmill Company. Stamp apparently experienced little difficulty in convincing British backers of the project for, in 1865, he returned with the tidy sum of 100,000 pounds—a king’s ransom.

Interestingly enough, Stamp’s first choice for beginning operations was what’s now Stanley Park. But (fortunately for posterity) he changed his mind and his mill site to eastward when he learned of the riptides there that would would have wreaked havoc with his log rafts.

This plaque in Stanley Park reads, “HERE Captain Edward Stamp, Pioneer Industrialist and Legislator, started lumbering operations, then finding a better site, he moved elsewhere on Burrard Inlet, and found in the wilderness, now the City of Vancouver, the famous Hastings Sawmill, 1865.”

His British backers’ confidence in Stamp’s business ability was readily justified when Stamp negotiated with Colonial Governor Frederick Seymour for a timber lease of 30,000 acres for 21 years at one cent per acre(!) and permission to import all of his equipment, duty-free.

Thus, on opposite shores of Burrard Inlet, Stamp’s Mill and Moody’s Mill came into being, the former consisting of the mill, a store and a four-acre collection of shacks and saloons.

A later visitor was unimpressed with the new township, terming it an “aggregation of filth” and “a running sore”.

Unlike Captain Stamp who seems to have run a less-than-tight ship, Sue Moody was one of the province’s first conscientious businessmen. Not only was his renamed Moodyville reasonably neat but it boasted of a library, school and electric lighting—luxuries as yet unknown in Victoria, New Westminster or, for that matter, any settlement north of San Francisco—and no saloon.

Stamp’s Mill, on the other hand, continued to grow topsy-turvy and was wide-open, its Indigenous and Kanaka loggers with a sprinkling of Scandinavian ship deserters, enjoying their choice of saloons which outnumbered all other business establishments. Consequently, when residents enthusiastically changed the settlement’s name to Hastings Mill, in honour of Rear-Admiral George Hastings, RN, Commander-in-Chief of the fleet at Esquimalt, he must have been something less than flattered.

Undisputed king of this wild and woolly congregation was Gassy Jack Deighton, after whom Vancouver’s Gastown is named. Jack had descended upon the settlement with nothing more than his Native wife, his in-laws, a servant, a barrel of whisky and six dollars in his pocket.

Despite this lack of wealth, and almost, overnight, Jack’s Globe Saloon opened its swinging doors to the thirsty loggers. A contemporary (and competitor) later described Jack as having been of “broad, ready humour, spicy and crisp and everglowing, of grotesque Falstaffian dimensions, with a green, muddy, deep purple complexion that told its own story.

“He had the gift of grouping words, which he flung from him with the volubility of a fake doctor.

“These words, shot at random, always hit a mark; unlucky would be the man whom Jack would nickname, for he would carry it as long as he lived.”

Across the inlet, under the stern eye of Sue Moody, residents displayed considerably more decorum, the timber magnate from Maine preferring married employees and favouring their building their own homes. Instead of spending their free hours exercising their elbows, Moodyville residents enjoyed the library and reading room of the Mechanics’ Institute. On Sundays, there were the services of the Rev. Ebenezer Robson.

Regardless of the loggers’ pleasure, or lack of, business grew on both sides of the inlet with ships from as far distant as Australia dropping anchor off the towns to load spars of Douglas fir and cedar.

Although force of business kept Moody in Moodyville much of the time he continued to call Victoria home where he married Janet Watson in 1869 and they had two children.

As early as mid-1868, Moody’s mill (now steam-powered) had shipped almost six million feet of lumber and 800,000 shingles compared with Stamp’s four million feet of lumber and 100,000 shingles. Another difference in figures was more noteworthy: Stamp had bellied up whereas Moody continued to prosper.

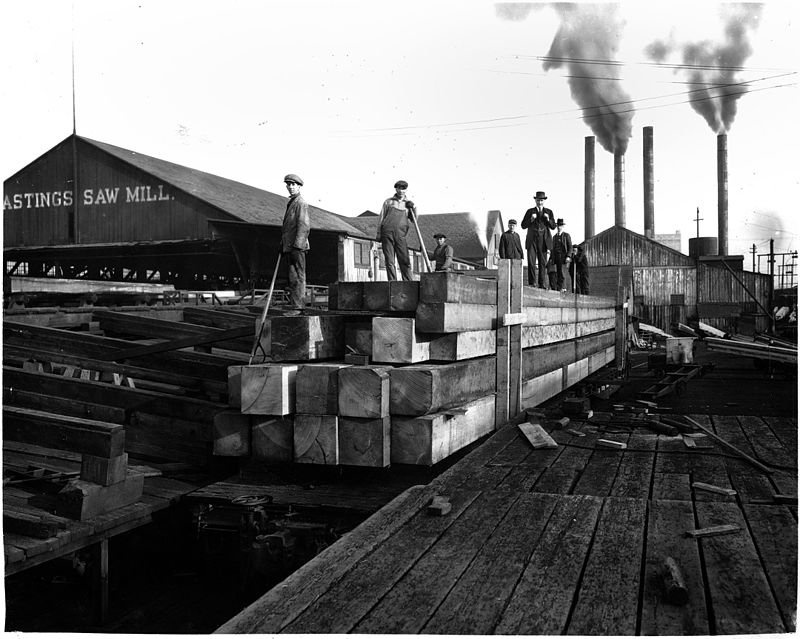

A load of prime first-growth fir beams just cut at Hastings Mill. —Wikipedia

As evidence of his financial health, he ventured farther afield by building a telegraph line between Hastings Mill and the Royal City. Moody had become so comfortable that when his mill burned down, he was merely inconvenienced and was soon back in production.

But that all ended in November 1875 when Moody sailed for San Francisco aboard the steamer Pacific. Within hours of clearing Victoria, the Pacific met disaster off Cape Flattery when she was rammed by the sailing vessel Orpheus.

In a matter of minutes the Pacific was gone, only two surviving of a company of more than 250. Among the dead was Sue Moody, beloved lumberman of Victoria and Burrard Inlet.

Old and overcrowded, the steamship Pacific sank in minutes when she was struck by the Orpheus which sailed on without checking for survivors. —Wikipedia

Mourned the New Westminster Herald: “A gloom was cast over the community by the receipt of the sad intelligence of the loss of the Pacific, many of the victims being known and esteemed here... One of them, Mr. S.F. Moody, was among the foremost men in the new Westminster district, and whose loss will be at once sincerely regretted and widely felt.

“Always ready to hold forth in manner, enterprising and energetic in business and the head of a large and wealthy firm—he was one whose place will not easily be filled.”

Many mourned the Maine businessman whose humour, honesty and regard for his workmen had made him universally popular. Few were prepared for the shock of learning that, in death, Moody was to have the last word.

This macabre twist occurred in Victoria when a resident walking along the Beacon Hill Park shore came upon a length of board, later determined to be a piece of wreckage from the hapless Pacific. What caught the beachcomber’s eye was the brief message which had been pencilled on its painted surface:

“S.P. Moody, all is lost.”

Immediate reaction to the discovery was that a “heartless hoax” had been perpetrated by someone with a perverted sense of humour who, upon finding the board on the beach, had written the message then launched the plank again.

But when friends identified the writing as being unquestionably that of Sewell Moody, it was “supposed that when the vessel as going down he wrote the inscription on one of the beams of the stateroom with the faint hope that the board would be found and his friends informed of his fate.

“If such were his purpose it has been attained by the casting up of the fragment after it had floated nearly 100 miles on the breast of the hungry sea, and reached the shore within sight of the deceased gentleman’s home. The feelings of a man taking leave of life under such circumstances can neither be imagined nor described.”

In Moodyville, all mourned the founder of Burrard Inlet’s lumber industry, the Mechanics’ Institute being filled to overflowing for the service conducted by Rev. Dinnick.

“Never on any occasion, religious or otherwise,” reported a witness, “have we seen the [reading] room so well filled and the number there was a sufficient indication of the kindly feelings of he community toward the deceased.”

Moody’s untimely death wasn’t the end of his company, however. According to the North Vancouver Museum and Archives, the historic mill operated until 1901 when the City of North Vancouver gradually absorbed the site, a process not completed until 1925, and Moodyville still showed on maps as late as 1932.

To put Moody’s triumph in historical context, “For the first two decades after British Columbia entered Confederation in 1871, the mill the mill was the largest single source of export revenue in the province.”

Today, Moodyville is a suburb of Canada’s third largest metropolis and continues to prosper under the name of North Shore. Residents have good reason to celebrate their heritage by recalling their area’s former glory—and to honour Sewell Prescott Moody, the timber prophet who showed the way.

The coming of the railway in the 1880s may have been Vancouver’s guarantee of maturity but it was lumber that rocked the cradle.

For years, Moody’s family kept the piece of weathered stanchion bearing his final farewell before presenting it to the Vancouver Maritime Museum. It’s a sad memento of that terrible day when S.S. Pacific foundered with her hapless hundreds and Sue Moody hastily pencilled a last goodbye on a broken plank.

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.