Shot Down On Christmas Eve (Part 1)

(First of 2 Parts)

“A crime as dark, cowardly and mysterious as ever disfigured the history of the province.”—Victoria Colonist

* * * * *

Dec. 24, 1890 – Christmas Eve in Victoria. Despite predictions of clear skies, evening brought rain.

For East Wellington storekeeper David Findlay Fee Jr., in town to visit his family and friends, midnight brought sudden, violent death.

It all began innocently earlier that evening with a masquerade party in the Philharmonic Hall on Fort Street. Among the celebrants were David Fee and Frank Partridge. Resplendent in their white costumes with red braid, they’d slipped away from the party to attend midnight mass in St. Andrew’s Cathedral.

St. Andrew’s Cathedral, Victoria. In December 1890 it was under construction and completed two years later. Since 1990 it has been a National Historic Site of Canada. —Wikipedia

Minutes later, they headed back to the hall. Passing the rising brick walls of the new cathedral, they crossed View Street and headed southward along the west side of Blanshard, towards Fort.

Their progress was suddenly barred by a man standing in the rain beneath an umbrella and apparently leaning on a walking stick. They moved to pass him by, at which the stranger muttered something. Partridge didn’t quite catch what he said, but later testified that was something to the effect of, “I challenge you.”

Both men, curious, turned to face him.

The popular Fee, a toy trumpet slung round his neck, was but four feet from the man under the umbrella who, to their horror, raised his ‘cane’—a double-barrelled shotgun—aimed it point blank at Fee and snapped a trigger.

The deadly blast caught him in the chest and spun him, lifeless, to the sidewalk, almost dragging down Partridge who’d been holding him by the arm. Partridge was so taken aback by the sudden, senseless attack that, upon recovering his balance, he stood motionless, unable to move as his friend’s killer dropped his umbrella and without another word, strode off down View Street, to vanish into a cottage just 30 feet away.

As startled churchgoers rushed into the street, Partridge looked down on the body of the young man who, moments before, had been alive and filled with the celebration of Christmas. Now Fee lay in a growing pool of rain-slicked blood.

In keeping with the surrealistic atmosphere surrounding what must be one of the most bizarre murders in Victoria history, one of the first to arrive at the scene was Supt. Harry Shepard, chief of police, who was among those whose Christmas church service had been shattered by the gunfire.

His first order was that Fee’s body be removed to the Philharmonic Hall from which Fee and Partridge had innocently departed less than half an hour before. As Supt. Sheppard and five of his officers hurried to the View Street cabin indicated as the killer’s retreat, a silent cortege carried the body to the hall and instantly transformed the “scene of revelry...to one of sadness”.

Approaching the cabin from the rear, police burst through the door and into what was described by a newspaper reporter as the quarters of a bachelor labourer.

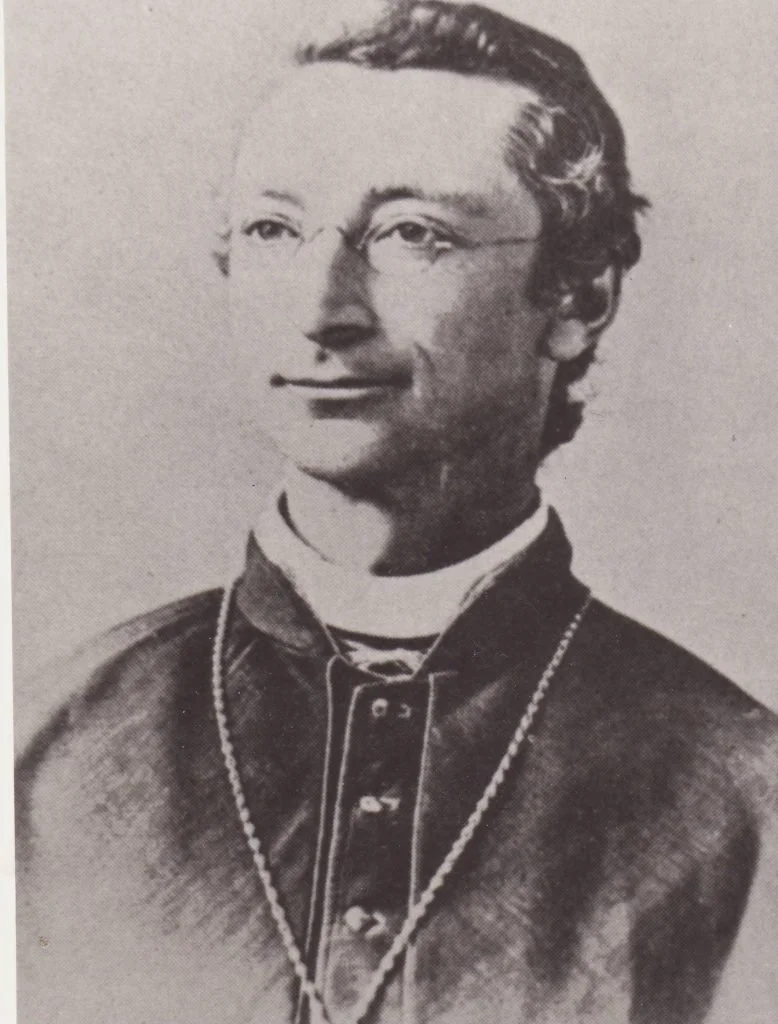

Although no one was at home, the murder weapon—barrel still warm—was lying in a corner. A search of the cottage turned up several letters addressed to George Taylor (apparently a stone cutter recently of Seattle), copies of the rules of the Young Men’s Institute, a picture of the late Archbishop Charles Seghers (martryred by a madman) “a regalia of some Irish society,” a large German pipe, tobacco and a half-emptied bottle of whisky.

There was a picture of Archbishop John Charles Seghers on the wall of the cabin where the murderer was last seen. Police wondered if it had any significance to Fee’s murder. (See the previous post, ‘The Murderer and the Madman’.)

Because the cottage stood on the cathedral building site, Chief Sheppard sent a runner in search of Aeneas McDonald, contractor, to learn which of his employees occupied it. In due course he was informed that a labourer named Joe Silk was the missing occupant, and an alert was issued for his arrest.

Results were soon forthcoming, Silk being apprehended within the hour on Blanshard Street. Protesting his innocence, Silk told Sheppard the man they wanted was his former roommate, Lawrence Phelan, who’d but shortly before confessed to him [Silk] that, while acting as watchman at the cathedral site, he’d shot a man who’d “threatened” him.

The almost ludicrous chain of events continued at the police station, to which Sheppard and his posse hustled the frightened Silk, sure he was, at the least, an accomplice to Fee’s shooting.

There, they found the object of their just-launched manhunt—in a cell.

The Victoria Police Department when Harry Sheppard was chief. —VPD

Lawrence Whelan, his correct name, had turned himself in. Jailer Bill Irvine, still dumbfounded, explained how Whelan had roused him from his bed with the starling admission, “I’m the man that shot a man tonight and I have come to give myself up.”

Brought before Chief Sheppard, the red-haired and mustachioed Irishman was calm and collected. Declining to make a full statement just then, he identified himself as Clarence W. Phelan (the police officer jotting down his few remarks seems to have misheard him), 33 years old and formerly of Dublin.

He concluded the interview with these intriguing words: “After the accident, I came at once to the police station, but found a crowd standing around the door. I was afraid that they would attempt violence, and so I thought I would take a walk around the block, and come back again. I did so. I was gone about an hour. I don’t deny that I killed the man.”

Many Victorians celebrated Christmas Day, 1890, quietly. In an age when everyone knew everyone else, young Fee had been a popular man about town and the circumstances of his death stunned one and all.

His parents operated a store at North Park and Quadra, and David, who for a year had managed a general store in the up-island coal mining community of East Wellington, had returned to Victoria for the holidays. His popularity can be judged by the tribute paid him by a Colonist reporter:

“...During his life long residence in Victoria, few young men made themselves more popular than the deceased. Everyone had a good word for ‘Dave Fee,’ as he was styled by all his acquaintances. He always took a prominent part in Pythian matters, was an enthusiastic fireman and always first in events of a social nature.

“His fearful and sudden death will be keenly mourned, and the greatest sympathy will be extended to his bereaved parents in this their hour of sorrow.”

The inquest opened in police court on the afternoon of December 6, spectators filling the galleries until they were elbow to elbow. Waiting silently in the dock, only a facial twitch betraying his nervousness, Larry Whelan was seen to be a man of medium height, with bright blue eyes, a bushy moustache and a face “that could not be called vicious”.

Neatly dressed in a black suit with stiff white collar and tie, he cast furtive glances at spectators who stared back, many of them with open hostility.

Chief Sheppard led proceedings by stating he had been at mass when, startled by a gunshot, he’d run outside to find, but a few yards distant, the body of David Fee. At Frank Fairbridge’s instruction he and five officers had stormed the Silk cottage where they recovered a shotgun with one barrel discharged and still damp from rain.

The gun and the umbrella picked up at the murder scene by Fairbridge were produced as evidence.

Fee’s friend and the sole witness to his death, Frank Partridge, then said that neither he nor David had done anything to provoke the attack. He had to admit that he didn’t recognize the confessed assassin.

Here, Partridge was challenged by Whelan who, acting in his own defence, referred to a “fish horn in your hand that you were blowing”. The young printer denied having been so armed but agreed that Fee had worn a child’s trumpet around his neck all evening.

Next to testify was Ed Wriglesworth, son of a saloon keeper, who identified the murder weapon as his own, saying Whelan had borrowed the shotgun—without shells—on Christmas evening.

The umbrella was tentatively identified by Ed Bermudiz who, as did Whelan, resided at the Dominion Hotel. He was reasonably sure that it was identical, but for a missing tassel, to one he’d loaned the accused. Questioned by Whelan, he vaguely referred to having routed a prowler from the church three weeks earlier when acting as night watchman.

The Dominion Hotel on Yates Street where Whelan resided is still with us as the Dalton Rocket Condominiums; as the Dominion Hotel, it’s on the Canadian Register of Historic Places. —www.templelodge33

John F. Harbottle, stone contractor for the new cathedral, said he’d been called aside in a Government Street saloon, shortly after midnight Christmas morning, by Joe Silk with this chilling and frantic whisper: “Larry says that he believes he has shot a man.”

Told that Whelan was waiting outside, the shocked contractor and a Mr. Sealey followed Silk to an obviously distraught Whelan who told them of having been bothered by troublemakers who, when ordered to show respect for the church, had blown a trumpet in his face.

Harbottle was unimpressed. With a laugh, he attempted to dismiss Larry’s story as that of a man “crazy all the time, from drink probably”.

At this, Whelan expressed some doubt whether he’d actually hurt the man and, to set him at ease, Harbottle (convinced that the watchman had imagined the whole thing) suggested that he and Sealey stroll along to the intersection of Blanshard and View to check it out while Silk and Whelan waited for their return at Harbottle’s house on Chatham Street.

Harbottle and Sealey, of course, quickly realized that Whelan had been all too accurate and hastened to urge him to surrender to police.

(To be continued)