Shot Down On Christmas Eve (Conclusion)

We’ve seen how, just after midnight of Christmas Day, 1890, David Fee Jr. was gunned down on a city street as he and friend Frank Partridge were returning to a Christmas celebration after attending midnight mass.

St. Andrew’s Cathedral, Victoria. Now a National Historic Site of Canada, in December 1890 it was under construction when its watchman, who supposedly was guarding the site, shot and killed young storekeeper David Fee. —Wikipedia

It was a shocking and apparently senseless crime: a case, it seems, of mistaken identity.

Was it a mistake?

Was there more—much more—behind this fine young man’s cold blooded slaying than was obvious?

* * * * *

When police stormed the cottage in which the murderer had last been seen, they found the murder weapon, still damp from the rain and warm from having been fired, several letters addressed to a George Taylor, copies of the rules of the Young Men’s Institute, a picture of the martyred Archbishop Charles Seghers, “a regalia of some Irish society,” a large German pipe, tobacco and a half-emptied bottle of whisky.

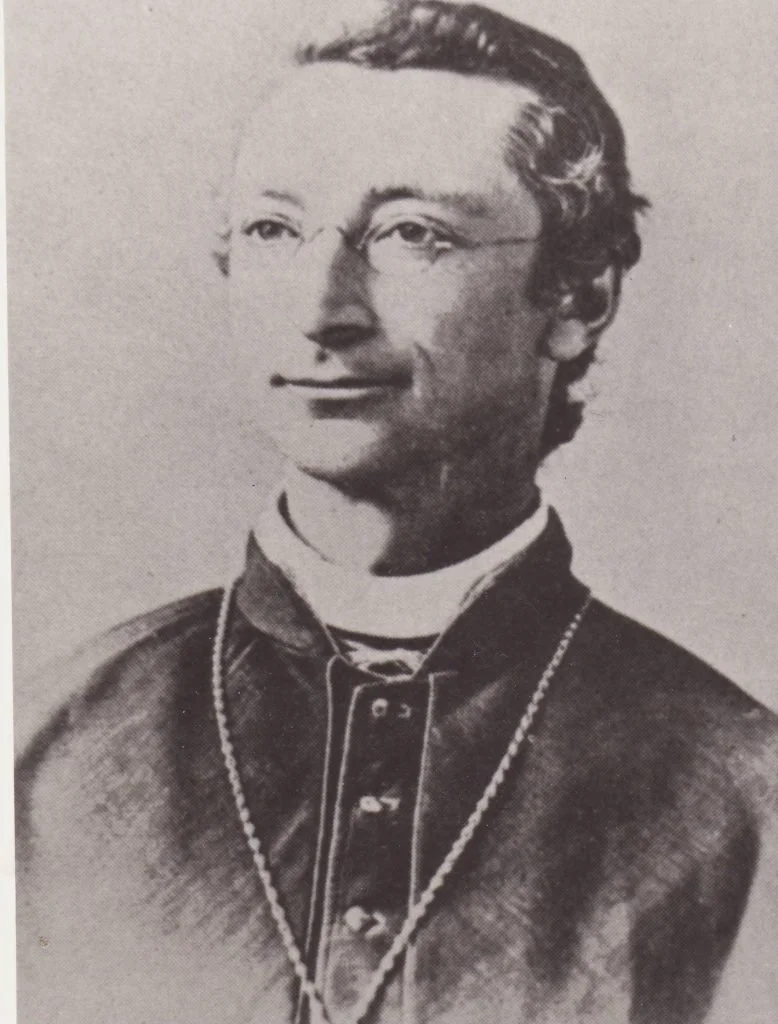

There was a picture of Archbishop John Charles Seghers on the wall of the cabin where the murderer was last seen. Police wondered if it had any significance to Fee’s murder. (See the previous post, ‘The Murderer and the Madman’.)

Because the cottage stood on the cathedral building site, Chief Sheppard sent a runner in search of Aeneas McDonald, contractor, to learn which of his employees occupied it. In due course he was informed that a labourer named Joe Silk was the missing occupant, and an alert was issued for his arrest.

Results were soon forthcoming, Silk being apprehended within the hour on Blanshard Street. Protesting his innocence, Silk told Sheppard the man they wanted was his former roommate, Lawrence Phelan, who’d but shortly before confessed to him [Silk] that, while acting as watchman at the cathedral site, he’d shot a man who’d “threatened” him.

The almost ludicrous chain of events continued at the police station, to which Sheppard and his posse hustled the frightened Silk, sure he was, at the least, an accomplice to Fee’s shooting.

There, they found the object of their just-launched manhunt—in a cell.

The Victoria Police Department when Harry Sheppard was chief. —VPD

Lawrence Whelan, his correct name, had turned himself in. Jailer Bill Irvine, still dumbfounded, explained how Whelan had roused him from his bed with the starling admission, “I’m the man that shot a man tonight and I have come to give myself up.”

Brought before Chief Sheppard, the red-haired and mustachioed Irishman was calm and collected. Declining to make a full statement just then, he identified himself as Clarence W. Phelan (the police officer jotting down his few remarks seems to have misheard him), 33 years old and formerly of Dublin.

He concluded the interview with these intriguing words: “After the accident, I came at once to the police station, but found a crowd standing around the door. I was afraid that they would attempt violence, and so I thought I would take a walk around the block, and come back again. I did so. I was gone about an hour.

“I don’t deny that I killed the man.”

At the inquest, filled to overflowing with curious and, it was said, hostile spectators, Larry Whelan was seen to be a man of medium height, with bright blue eyes, a bushy moustache and a face “that could not be called vicious”.

Chief Sheppard told how he’d been at mass when, startled by a gunshot, he’d run outside to find, but a few yards distant, the body of David Fee. At Frank Fairbridge’s instruction he and five officers had stormed the Silk cottage where they recovered the shotgun produced as evidence with one barrel discharged and still damp from rain, and an umbrella.

Fee’s friend and the sole witness to his death, Frank Partridge, testified that neither he nor David had done anything to provoke the attack and he hadn’t recognized the confessed assassin.

Challenged by Whelan who was acting in his own defence, the young printer denied having blown on a “fish horn” but agreed that Fee had been wearing a child’s trumpet around his neck.

Saloonkeeper Ed Wriglesworth identified the murder weapon as his own, saying Whelan had borrowed the shotgun—without shells—on Christmas evening. The umbrella was tentatively identified by Ed Bermudiz who, as did Whelan, resided at the Dominion Hotel. He was reasonably sure that it was the one he’d loaned the accused.

Questioned by Whelan, he vaguely referred to having routed a prowler from the church three weeks earlier when acting as night watchman. To Whelan’s question, Harbottle conceded that he’d heard the accused slayer say that the shotgun, intended to scare off “pranksters,” was loaded with blanks.

Former roommate Joe Silk elaborated on this point, saying that he had, in fact, provided Whelan with blank shells two hours before the shooting, the latter having expressed a desire to “fool the fellows that come around playing tricks”.

He further described how the watchman, much alarmed, burst into his cabin at midnight, shotgun in hand, to breathlessly inform him that he’d shot a man “to save myself”. Silk, who couldn’t understand why he, too, was under arrest, had taken Whelan to the Monarch Saloon to confer with John F. Harbottle, stone contractor for the new cathedral.

Harbottle told how Silk had called him aside in a Government Street saloon, shortly after midnight Christmas morning, with the chilling and frantic whisper, “Larry says that he believes he has shot a man.”

Told that Whelan was waiting outside, the shocked contractor and a Mr. Sealey followed Silk to an obviously distraught Whelan who told them of having been bothered by troublemakers who, when ordered to show respect for the church, had blown a trumpet in his face.

Harbottle was unimpressed. With a laugh, he attempted to dismiss Larry’s story as that of a man “crazy all the time, from drink probably”.

At this, Whelan expressed some doubt whether he’d actually hurt the man and, to set him at ease, Harbottle (convinced that the watchman had imagined the whole thing) suggested that he and Sealey stroll along to the intersection of Blanshard and View to check it out while Silk and Whelan waited for their return at Harbottle’s house on Chatham Street.

Harbottle and Sealey, of course, quickly realized that Whelan had been all too accurate and hastened to urge him to surrender to police.

John Crawford, a young construction worker, told how he’d met Whelan in the bar of the Dominion Hotel earlier Christmas Eve. Whelan was armed with a shotgun and an umbrella and both workmen (apparently having made an early start to their celebrating) began to practise military drill with the “weapons”.

Crawford had been sober enough to check the shotgun first, noting that it wasn’t only empty but that rags had been stuffed into the barrels to keep out the rain.

Asked why he needed a gun, Whelan replied that he knew employer McDonald liked to play tricks on his watchmen. “If he comes around, playing tricks on me, I’ll give him a charge of shot!”

When Whelan left to take up his post, Crawford tried to talk several others into “having some fun; let’s go around and see him,” but he couldn’t find a single adventurous soul to accompany him just one block to the cathedral construction site. Crawford then headed out alone but not finding Whelan at the church, he checked the Wriglesworth saloon and was assured that Larry was standing watch.

Crawford was about to give up when he encountered Dennis Dacey and talked him into having some fun at Whelan’s expense. At the church they found Whelan and Joe Silk. When Crawford made as if to enter the cathedral, Silk tersely advised him, “Don’t go in, the gun is loaded.”

Crawford, who’d examined Larry’s weapon earlier, snorted that he knew it to be harmless.

Silk insisted that the shotgun was loaded with live ammunition, at which Crawford demanded that Larry show him the weapon. Whelan refused to hand it over but the frustrated practical joker managed to break open the weapon and see there was a shell in each breech.

Shocked, Crawford ordered the drunken watchman to empty the gun but Whelan, sulking, stalked off into the darkened cathedral. Only when Silk swore that he wouldn’t leave Larry unattended did Crawford depart to resume his holiday festivities.

Dr. John S. Helmcken; he and Dr. Davie made the startling discovery that Fee had died from the devastating effects of a solid, home-made slug rather than the anticipated charge of buckshot. —Wikipedia

The inquest was reconvened on December 29 before an even larger audience. Drs. Helmcken and Davie who’d examined Fee’s body, had expected to find it peppered with fine shotgun pellets. Instead, they found a single wound from a “murderous looking slug...of lead, apparently hammered into the form of a ball, but larger than the ordinary rifle ball.”

This crude projectile had torn a hole two inches wide through Fee’s heart and lodged itself against his shoulder blade. Death had been instantaneous.

Chief Sheppard, recalled to the stand, stated that a search of Joe Silk’s bedroom had yielded 26 shotgun shells, all but one of them empty of shot, and loading equipment. (Shotgun shells were of brass in those days and could be recycled—Ed.)

Returned to the stand, Silk repeated his earlier testimony that the shells he’d given his friend were blanks. He firmly denied having warned Crawford that the shotgun was loaded; he said he’d suggested that Larry might shoot somebody so as to scare Crawford off.

He concluded by declaring that Whelan, on the job as watchman for the first time, wasn’t drunk.

It’s at this point that an entirely new slant on the shooting was introduced.

City fire chief Tom Deasy told of an argument he’d had with Whelan about an American flag, trimmed in green, which had been hung from a derrick at the cathedral construction site at the laying of the cornerstone ceremony. Whelan, obviously in sympathy with current Irish unrest and its American (Fenian) offshoot, threatened anyone who tampered with the banner of defiance.

Contractor Aeneas McDonald corroborated the flag testimony, saying he’d had the Stars ‘n’ Stripes hauled down. Three times on Christmas Eve, he’d checked the building site for his watchman; each time he’d found the cathedral to be unguarded. He hadn’t known that Whelan was armed and said he wouldn’t have allowed it.

It was at the last sitting of the inquest that the coroner submitted, as motive, that Whelan, enraged when the Fenian symbol had been removed, and blaming Chief Deasy, shot Fee by mistake. A blotter, taken from Silk’s cottage, bore the ominous words, “He will never speak again.”

On Christmas Eve, surmised the coroner, a drink-befuddled Whelan had mistaken Fee’s and Partridge’s white costumes for the white raincoat usually worn by Deasy!

Whelan was committed for trial, Silk charged as an accessory before the fact. Five weeks later, Whelan stood alone before the formidable Chief Justice Matthew Begbie—the ‘Hanging Judge.’ He’d been convicted by a jury of his peers, not of murder but of manslaughter.

It’s pure legend that Matthew Begbie was a “hanging judge” who was eager to condemn men to death. There’s no mistaking, however, that he was outraged that the jury voted to spare Larry Whelan from the gallows. —Wikipedia

Begbie seems to have interpreted as an attempt by the jurors to save Whelan from the gallows by convicting him of the lesser charge. Terming the prisoner “a drunken, quarrelsome fellow,” Begbie tore into him with an impassioned 300-word tirade, which concluded in these memorable words:

“...Never again will you be allowed to call yourself a free man; never again will you be allowed to carry on your drunken brawls; never again will you carry your flag over your shoulder and challenge a fight; never again will you shoot down, like a dog, an estimable young man, a worthy citizen.

“Believing you guilty of wilful murder, I will protect you from the dogs. You shall not be torn to pieces by your indignant fellow citizens. You shall go from here to be made miserable, to be a slave for the rest of your life. You are not going to a home, an asylum, a refuge, but to prison where you shall work without hope of freedom and reward for all the rest of your life.”

Ten years later, by order of the federal department of justice, Whelan was released.

Such was the extraordinary case of David Fee’s encounter with a drunken watchman. Such was Christmas in Victoria, 132 years ago.