Six Weeks of Death

So the late great B.C. historian B.A. McKelvie titled this manuscript, seven decades ago. I just found it in my archives; I really must shuffle my files more often.

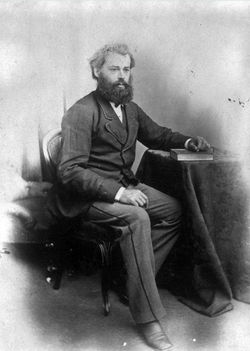

Bruce Alistair (“Pinkie”) and Mrs. McKelvie. —Courtesy Phyllis Bomford

For those who don’t recognize his name, B.A. McKelvie was a leading provincial journalist and the foremost historian and writer of ‘popular’ B.C. history in the 1920s-’50s. He was gone when I, a kid, history buff and aspiring author/historian, discovered him during my first visit to the BC Archives while looking for such serious topics as lost treasures, shipwrecks, stagecoach robberies...

McKelvie had been there, done that, decades before me. Not only did he leave a legacy of his historical research and writings, he inspired me. He’d made a career of writing about our colourful past; why couldn’t I?

Sure, he’d had a day job as a senior reporter and editor in Vancouver and Victoria, but that was a mere detail and, millions and millions of words later, here we are.

Vancouver-born of Scottish parents from Quebec in 1889, McKelvie’s first job was as a printer’s apprentice at a newspaper. In 1913, after several jobs that included a failed attempt to start his own newspaper in Ladysmith, he became a police reporter for the Vancouver Daily Province—a job so eventful that, besides his notebook, he packed a .25 automatic pistol with him!

A job so eventful that he was there the day the city police chief was gunned down by a crazed drug addict; he attended another notorious police-killer ‘Flying Dutchman’ Henry Wagner’s hanging. And he also reported, firsthand, the famous confrontation between a federal government determined to deny entry to 100s of equally determined East Indian immigrants aboard the S.S. Komagata Maru in Vancouver Harbour.

The ‘Komagata Maru Incident’ is considered a seminal event in B.C. history, and young newspaper reporter Bruce McKelvie was there. —Wikipedia

He must have found following years as an editor with the Vancouver Sun and the Victoria Colonist quiet after his exciting days as a police reporter, and occupied himself with establishing a reputation as an historian and writing books on B.C. history.

Some of his manuscripts were among the treasures in a large box of personal papers—letters, documents, manuscripts and some photos—that late family member Phyllis Bomford kindly gave me 15-20 years ago.

Also included were several typescripts that, so far as I know, have never been published. Let’s correct that here and now with ‘Six Weeks of Death,” B.A. McKelvie’s rousing tale of shipwreck. (It’s the first time I’ve seen canary copy paper in years.)

* * * * *

Six Weeks of Death

by B.A. Mckelvie

A single grave at Quatsino and the resting places of two unknown seamen at Ucluelet recall how two fine British sailing vessels perished on the jagged reefs off Vancouver Island’s storm-beaten West Coast within a few days of each other during that awful “six weeks of death” extending from December 13, 1905 to January 24, 1906.

Within that tragic period the crashing, thundering waves ground three staunch craft to pieces against the rocks, and claimed 162 lives. Eight of the personnel of the first victim of the Storm Fury gave up their lives; all on board the second one, some 37, perished, while the third one, the Valencia, marked her loss with 117 dead.

The story of the Valencia is well known. This is an account of how the other ships were destroyed.

Fifty [sic] years ago not much was known about the shifting drift that set up off Swiftsure Bank, at the mouth of the Strait of Juan de Fuca, when high winds blew from certain directions. It was known that there was a usually constant current that varied little in flow or direction during moderate weather. This, however, it was later learned, took on a different set and speed during heavy gales, and contributed largely to the evil reputation as the “Graveyard of the Pacific,” that was given to the West Coast.

The U.S. Government established a lightship at Swiftsure Bank but it didn’t help the King David or the equally ill-fated Pass of Melfort from destruction in the ‘Graveyard of the Pacific.’ —Wikipedia

All three disasters in that deadly six weeks may be charged against the vagaries of [this] shifting drift, and the fact that they were not included in sailing directions or marked on charts.

It was about December 13—as well as survivors could recall, for they almost lost track of time in their misery—that the British ship King David, Captain Davidson, from Salinas Cruz in ballast for Puget Sound, dragged anchor and struck on the dangerous Bajo Reef, about 10 miles from Nootka.

The vessel made the entrance to the Strait of Juan de Fuca on December 7, all on board looking forward to spending the Christmas season in port. There was a high wind outside and fog within the Strait, and the King David was unable to weather Cape Flattery. She beat off and, three days later, made a second attempt to make the Strait, only to run into more mist.

The lookout man, during a momentary break in the swirling grey curtain, thought he saw breakers, and could hear the pounding surf.

The anchors were dropped. For three days they held, and all that time the fog persisted. It was on the unlucky 13th that the captain caught sight of land and could appreciate the extreme danger of the situation.

As the visibility cleared the wind rose. Captain Davidson ordered the anchors lifted and an attempt made to beat away from the adjacent rocks. But the anchors did not come free; they dragged on the rocks. Every device of marine skill known to the captain and officers was tried, but to no avail; the big ship drew steadily closer to the white breakers that showed the lethal rocks of Bajo Reef.

Then with a grinding crash the King David struck on the starboard quarter with such force that two knuckles of stone broke through the steel plates and held her fast.

Later in the day, when the tide receded, it was considered wise to send the older men and apprentices ashore with the second mate. They were instructed to take shelter in an abandoned Indian shack that could be seen about a quarter mile away. The captain, first officer and the remaining seamen continued on board of the wreck. During that time, under direction of Steward Duncan McFarlane, a good store of supplies was got ashore.

In making the first landing the old sailmaker, Donald Mcleod, fell into the sea and was rescued with some difficulty. The experience unbalanced his mind, and he became so violent that he had to be restrained.

After the three comparatively quiet days the wind rose again and the strain on the vessel caused the stays of the mainmast to give. Captain Davidson ordered abandonment of the vessel, and although the sails had all been furled to lessen the strain on the masts, the wind soon tore and shredded the canvas on the main topmast.

Large fires were started on the beach to attract the attention of passing vessels. None saw them. The weather was cold, and the poor wretches were soaked with rain and sleet most of the time. Some days passed. The picture was not very bright. The only chart that the captain possessed of this coast showed very little. Cape Beale was the only place indicated as being inhabited on the West Coast.

Then two sailors volunteered to go in search of habitation to the Nor’west. They were gone for three days and returned with a wild tale of having gone a distance of 25 miles when they met an Indian who told them that no help could be expected before March. Nootka was less than 10 miles away in the direction they claim to have gone!

As a result of the picture given by the seamen, First Officer A.W. Wollstein, a young and capable New Zealander, offered to take a boat and try and get to Cape Beale. It was their only hope, and the captain consented. Six men volunteered to form the crew of the longboat. Their names should be remembered in this saga of the sea.

They were John Rogers, Liverpool; H.G. Ray, Newport, Wales; Evan Jones, Carnarvon, Wales; Martin Pedersen, Norway; J. Polda, Denmark, and P. Sorensen, Denmark. They knew they were going on a dangerous mission, but cheerfully pushed off and headed south east—and the mist closed in about them. They were never seen again.

At first those who were left shivering on the beach—for even those attending the fires could not keep warm when the wind howled and the sleet cut their faces and hands—were expecting that Wollstein and his men would bring them rescue.

But as day dragged after miserable day hope commenced to fade, and it was now felt that perhaps the boat had been caught in the gale that swept along the Coast from December 23 until two days after Christmas.

It was on January 19 that the CPR steamer Queen City, Captain Townsend, was making towards Nootka on her run from Victoria, when sight was caught of the fluttering rags of canvas from the still standing mast of the King David. The Queen City approached closely as possible and saw waving men on the beach. Captain Townsend signalled that he would return for them, and then went on to Nootka. But he had scarcely reached that place when he noticed that the glass had started to go down.

Fearing an approaching storm, the S.S. Queen City raced back to rescue 18 survivors of the King David. —BC Archives

Without loss of time he turned and raced back to where the wreck lay. Already there was every evidence that a storm was brewing, but he managed to get the survivors off the beach: Davidson, Second Officer W.E. Edwards, four apprentices and a cabin boy; eight seaman, and the delirious sailmaker. The condition of McLeod became worse, and when the Queen City lay for several days stormbound at Quatsino, the poor fellow died. His shipmates buried him there.

Such, then, is a brief outline of the first victim of the sea on the West Coast in that “six weeks of death”.

The Pass of Malfort was a four-masted steel bark of 2291 tons net registry. She was owned in Glasgow and was a splendid example of the Scottish ship-building art. A graceful craft, she had an overall length of 298.8 feet, a beam of 44 feet and a depth of 24.5 feet. She was in-bound to Port Townsend in ballast for a cargo of lumber.

It was Christmas Day that she attempted to enter the Strait of Juan de Fuca. It was thick weather, and she could not measure the speed with which the treacherous drift was carrying her from her estimated position off Cape Flattery towards the hungry reefs in the vicinity of Barkley Sound.

It was a terrible night. Indians, on the morning of December 26, heard rockets. One or two natives ventured out into the cold rain and howling gale from their huts on the other side of the promontory away from Amphitrite Point. They could, however, neither see nor hear anything and returned to the shelter of their homes.

A new whistling buoy had been placed off the Amphritite reef, but it had been carried away in a recent storm, and search had failed to locate it, so even the chance of such a warning being conveyed to the Pass of Melfort had been eliminated.

Captain Google Scougall, his officers and men had no chance of averting a wreck. The powerful current carried the bark directly towards the shore, and then the mighty, seething waves lifted the proud craft high and slammed her down, a pitiable, helpless thing on the rocks.

In the few moments before she was broken, the desperate men, and one woman—the captain's wife—fired rocket after rocket into the wet curtain of the night. The Indians heard, but could not locate the wreck—and by that time there probably was nothing to be seen.

It was the following morning that Captain James Gaudin, Dominion Government agent Marine Agent, received a wire from A.H. Lynch, Ucluelett. It read: “Vessel went ashore last night, quarter mile east of Amphitrite Point. One body has been recovered, dressed in oil skins and overalls; two more seen washing in the surf, but it is impossible to reach them.

Captain and Marine Agent James Gaudain was informed of yet another shipwreck, this one off Amphitrite Point. —www.findagrave.com

“Several ship’s buckets, marked ‘Pass of Melfort,’ a barometer, some cabin wreckage, boat hooks, smashed boats; the figurehead of a woman painted white, and much wreckage is in a small rocky bay. There is no wreckage on either side of it. My opinion is that the vessel is very close to shore; they are evidently anchored. A torn paper with the name single ‘John Huston’ on it, apparently a part of a log book and a large photograph of 15 men taken at break of poop, evidently of the captain, apprentices and some of the crew.

“Everything possible is being done to recover more bodies."

But it was only possible to recover one more body from that wild sea by the time that the salvage ship Salvor, Captain Charles Harris, reached Ucluelet. There was no priest or minister to give a Christian burial to these unknown men, but W.M. Mackenzie, the local storekeeper, in order to give them some form of decent internment, agreed to read the burial service from the Church of England prayer book. As the little handful of residents, Indians and men from the salvage vessel gave reverent attention, the service was carried out.

And the cruel Fates—not satisfied with the human sacrifices exacted by the storms—added a bizarre evil touch. As the kindly storekeeper was conducting the burial service, his home and store burned down.

As far as could be discovered there were 37 victims to the wrecking of the Pass of Melfort. The broken and twisted mass that had been a fine bark was pushed across the reef into deeper water.

* * * * *

So wrote B.A. McKelvie, four years or so before his death in 1960. In my own way, and 100s of stories about West Coast shipwrecks later, I’ve been following in his footsteps all these years.