From Shetland to Vancouver Island

Eric Duncan is remembered for having written what has been described as “the most important document for the history of the Comox Valley,” From Shetland to Vancouver Island: Recollections of Seventy-Five Years.

Pioneer Comox Valley chronicler Eric Duncan. —Author’s Collection

Published in Edinburgh in 1937, it’s a fine read but long out of print. Happily, I’ve had a copy—a first edition, to boot—for years and have read it twice. It was, in fact, one of my earliest antiquarian book finds.

Recently, I scanned it again and found a chapter which I’m sure will please Chronicles readers.

* * * * *

Sketches of some pioneers and Old Timers

by Eric Duncan

When the Burrages left their place by the Indian village in 1866, they leased it to the Hudson's Bay Co., who sent up an agent of theirs from Nanaimo –Adam Grant Horne, an Orcadian, as were many of their employees at that time. They built him a dwelling-house, with a large fireplace and chimney of English brick brought around Cape Horn.

The house is still standing, but the bricks were lately removed. Horne was well acquainted with the language and habits of the Indians, but he found the location rather quiet. When I came, he owned the only buggy in the district, and the business was very small. I remember him saying, "My son and myself have stood a whole day behind that counter for one dime.”

Adam Horne had had a distinguished career with the Hudson’s Bay Co.; his assignment to the Comox Valley must have been a letdown. —BC Archives

One peculiarity about Horne, which I never saw in anyone else, was that although he wrote like copper plate he blundered in spelling the commonest words. When the Company dropped the business as unprofitable, he moved back to Nanaimo and kept the grocery store on Victoria Crescent for a long time, where he also handled farm produce from Comox. His son was postmaster of Nanaimo for 50 years.

George Ford, from Gloucestershire, sailor and Australian, was original owner of the Finley farm, the best place on the upper road. A year after he came his potatoes were cut down by frost in August, which so disgusted him that he deserted the place, and made an arrangement with Henry Maude, west of the Tsolum River, to go with him to Hornby Island and raise sheep, there being a whole stretch of open land there and no wild animals.

Both these men married Indian [sic] wives, and stuck by them. Ford's holding included all the open land of agricultural value on the island, and it was on his place that I first saw the mis-named “Canada" thistle, which old manor-house records show to have been a fodder plant in England more than 300 years ago.

Besides sheep, Ford raised a crowd of lusty boys, the famous Ford Brothers.

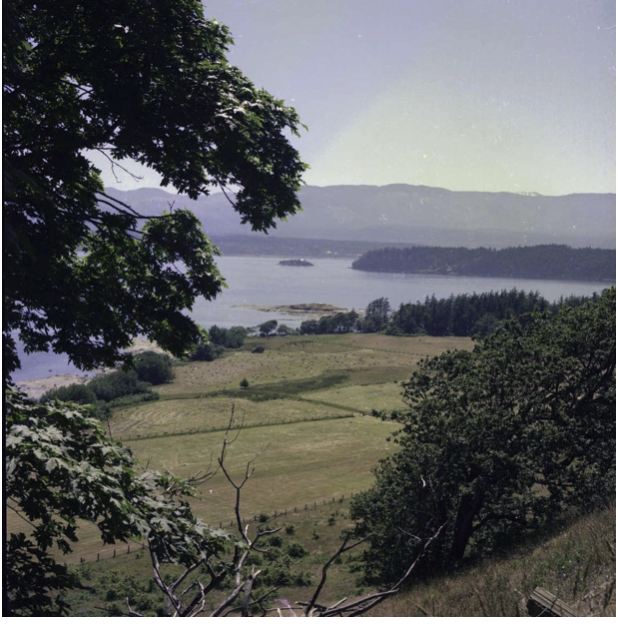

Pastoral Hornby Island in 1975. —BC

Maude had no family, but his estate encircled the whole of Tribune Bay, and is now a summer resort. He complained to me of the prowess of his sheep, saying they were too strong for him to handle. Unlike Ford, who was uneducated, he was of good lineage, a connection of the late General Maude of Mesopotamia, and he had a set of Chambers’s Encyclopedia, besides other books. His friends in England sent him the 9th edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica, and I then tried to buy his Chambers’, but he would not sell.

He always had an unhealthy look, as of a man who had got old before his time. Being at Victoria in the spring of 1888, I heard that he was passing away at the Old Saint Joseph's Hospital, and called, but he was in a comatose condition.

There were no settlers on Denman Island when Ford and Maude went to Hornby. It was the naturally open land that attracted them, and Denman being heavily timbered had to wait for the Eastern Canadian axemen, who came some 10 years later.

Robert Ritchie, Glasgow baker and Australian, had that large farm on the upper road, the north half of which is now occupied by the Ball family. Most bakers are shrunken and pale through the inhalation of flour dust, but he was a big florid man, and helpful to his bachelor neighbours with hints on baking, though most of them did not profit thereby, but ruined their health with saleratus [baking soda] concoctions.

A prosperous Comox Valley farm ca 1911. —BC Archives

He sold out for $3,000 in 1884, and leaving most of the cash in the Dominion Savings Bank at Victoria, went on to San Francisco, where he disappeared and was never heard from again. He had been thought single, but in 1934 a daughter-in-law turned up in Melbourne, and she got the money, which had been in charge of the Canadian government for 50 years.

One of Richie's late successors on the farm was Markham Ball, a good and highly intelligent young Englishman from Nottinghamshire, who, I believe, shortened his life by hard work.

The south half of this same farm reminds me of a rather queer episode. During the Great War it was bought by the Soldier Settlement Board for the use of returned men, and a young fellow named Hal Symons was the first to be located on it. He had been used to farming and was no dunce in other ways, being a good performer on the piano and organist for some time at the local Presbyterian Church.

I had heard he was from Dorsetshire, and meeting him on the road one day, the following colloquy ensued: “You are from Dorsetshire?” “Yes, born and brought up in Dorsetshire.” “What do you think of {English novelist and poet] Thomas Hardy?” “Thomas Hardy—Thomas Hardy—I don't think I know the name.” “But you have heard of him? He lives in your town." “No, I don't believe I have. What business was he in?”

Famous English novelist and poet Thomas Hardy. Pioneer Symons: “Thomas Hardy, who?” —Wikipedia

Well, I gave up then. Probably the only world-figure that the little place has ever produced, and he had never heard of him! Such is fame.

Adam McKelvey, Irishman and Australian, was an outstanding figure among the pioneers, having one of the middle sections of fine bottom land west of the Tsolum River. Cameron and McCord, his neighbours to the south, did not stay long, and he took over there holdings, thus securing 300 acres of the best land in the Valley, where he grew potatoes “as big as your fut.” He was long thought to be single, but at last brought out a wife and grown-up son from Ireland.

His wife was a good dairy woman, and James Harvey, Nanaimo grocer, “subtracted” to take all the butter she could make, so McKelvey soon became a moneyed man. Before the Canadian Pacific Railway got across, the only paper currency in general circulation through the Province were the notes of the banks of British North America and of British Columbia, both of which institutions were later absorbed by Eastern banks, but by some means McKelvey had come into possession of a $10 bill of the Bank of Ottawa, which he wanted to change.

As several $10 bills of the Confederate States (which were worthless) had been passed around, the local dealer to whom he applied was a little dubious of the strange bill. “Oh, but,” said McKelvey, "that's the Bank of our country. If that Bank is no good, then our country is gone in."

Today, real Confederate money is valued as a collectible; at the time of which Duncan is writing about, it was worthless although sometimes passed successfully to unsuspecting victims. —Heritage Auctions

At that time there was a boom in Port Moody lots, as the supposed railway terminus, and McKelvey bought one. But when he went to see it, he said he could not stand on it, as it was measured from top to bottom of a cliff overhanging the sea.

In his younger days McKelvey worked hard and well, but getting older he took more leisure and became an adept angler. He always fished alone, and brought home many a good string, and when asked how we did it, he said he pulled a grey woollen thread from his sock and knotted it around the hook.

He was not a bad fellow when sober, but when liquor was in him he became vicious. Samuel Cliffe of the Lorne Hotel had a big black beard of which he was proud, and on one occasion when he had a row with McKelvey, the latter tore a big handful out of one side of it. Poor Sam had a weary time trimming it before it regained its original symmetry.

Long a popular landmark of the Comox Valley, the Lorne Hotel. —BC Archives

McKelvey's wife was considerably older than himself, and after she died he took a trip back to Ireland and married the younger sister of his daughter-in-law, bringing her out along with him. His life in Australia was a favourite topic, where "a drink o’ wather an’ a drink o’ whisky cost a shilling apiece, an’ ye'd ruther take the wather.”

It would have been well for him if he had followed this maxim in British Columbia, for, as the years grew on him, the liquor habit grew also, and finally finished him.

The story of his opulence brought out a whole crowd of young Ulstermen to the district. There were three McQuillans, three Gilmours, two Crockett's, two Surgenors, two Steeles, a Johnson and a Morrison. Some of them stayed and some went elsewhere, but they were all good workers.

North of McKelvey, on a compact and open little farm of 120 acres, was another Irishman and Australian, James Clarke, who's bright bushy hair and white freckled skin reminded one of “Life-in-Death” in the Ancient Mariner. He lived in a log hut sunk to the roof in a hillside, and his only table tools were a big spoon and butcher knife.

When he got tired of oxen, he worked a pair of speckled cayuses with harness made from strips of green cowhide. In the middle ‘90s a nephew of his, a man of 35, named Patrick Byrne, came over from the States and stayed awhile with him, but finally left. He had got his mail at Sandwick, his nearest post-office, and he told me, as postmaster, on leaving, that he had put in six months trying to induce Clarke to build a decent house and “live civilized,” but he had failed and was never coming back again.

Some 18 months later Clarke told me he was dead. Clarke himself ended up in the provincial mental hospital.

A brother, Daniel, and two sisters, named O'Grady and O'Rooke, all in County Louth, Ireland, were the nearest heirs, and, like all Old Country people of that generation, they thought their relative in “Americkay” must be rich. Daniel, in particular, wrote insisting that his brother had “walth,” and that either it was hidden, or “Pat” Byrne had got it.

Drake and Jackson, Victoria lawyers, managed the estate, and I understood it took all the livestock and cash to pay Clarke's expense at the asylum. The farm was sold to a hard-working Scots family name Vass, from the coal-mines of Cumberland (who are still on it), for $2,500 and the money divided among the heirs.

It’s easy to see why the Comox Valley, although far removed from “civilization” in the 1860s, drew farming pioneers. —BC Archives

And now we come to the last of note among the pioneers, William Beech, who outlived all his companions, and died in 1931 at the age of 98. He was a small, spare man from Staffordshire, and a sailor before locating here. In 1870 he sold one of the best farms to raise funds to go back to his native place for a wife—a wife who stuck by him faithfully through all his long after-life and now survives him.

Returning with her in 1872 he took up a portion of good alder bottom land, and in over half a century did not sleep five nights off it.

Beech had none of the modern fear of large families. “Children are wealth," he told the writer more than 40 years ago, and just as soon as ever they were able to set them to work on the land, and thence-forward did little himself but supervise. Year after year he could be seen seated on his veranda, pipe in mouth, watching his boys and girls busy in the fields below. They married early and cleared out; but as fast as the older ones went younger ones took their place, and even grandchildren came back under the yolk.

In early days huge droves of swine helped with the plowing, and Beech never forgot that. He advised new-comers to get all the land they possibly could under crop, no matter how roughly: “Scratch, or burn, or blacken the surface somehow, and throw in your seed." His tools and machinery were primitive, he lived substantially on what he raised, he held fast to the maxim of old Polonius—“Neither a borrower nor a lender be” and so he kept to carefree mind.

Spry nearly to the last, he left a host of descendants.

Joseph Rodello, an English-speaking Italian, who had been one of Garibaldi’s soldiers, was the first and chief customer from the Robb town lots. He bought the ground on both sides of the road at the head of the wharf, and built on the east side a large rambling store, and on the west the old original Elk Hotel. For a good many years he was storekeeper, hotel-man, tax collector and postmaster; but he had the help of [land surveyor George] Drabble in the two latter offices, and about the time that I came, he rented out the hotel.

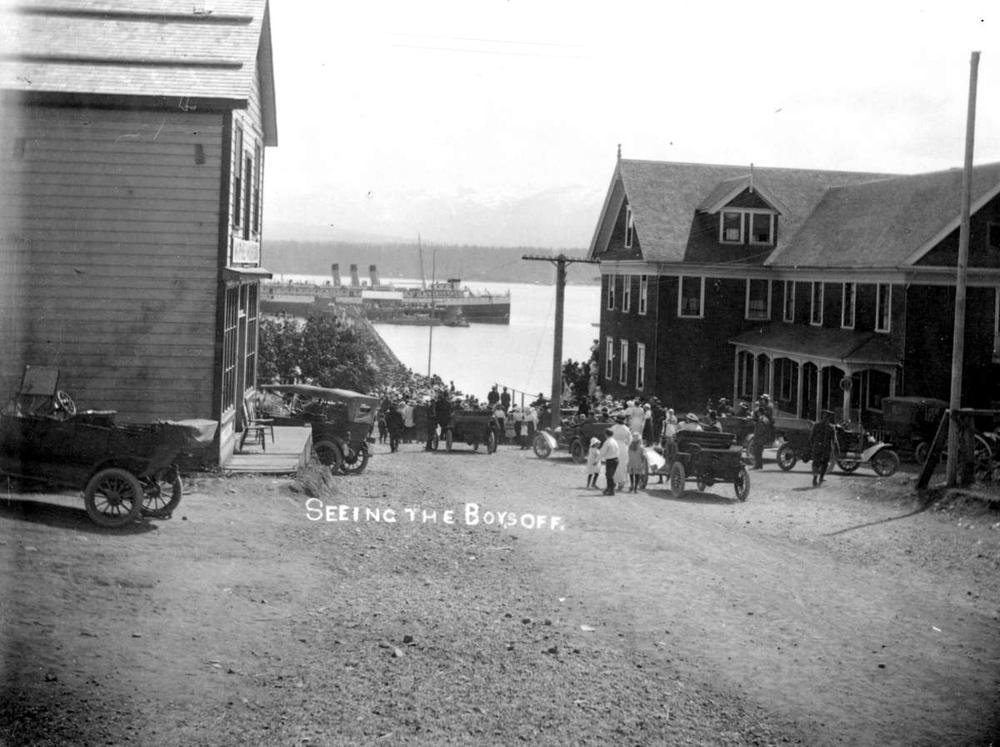

Downtown Comox, 1911, the Lorne Hotel on the right. —BC Archives

John Fitzpatrick was an American carpenter and builder, who erected many of the early dwellings and barns, and he did good substantial work. He and his wife leased the Elk Hotel from Rodello and conducted it for several years. Then Fitzpatrick bought a large lot from the Robbs on the top of the hill which slopes down to the wharf, and there he built the Lorne Hotel—so long connected with the house of Cliffe. The Marcus of Lorne being then Governor-General of Canada accounts for the name. After running it a few years Fitzgerald sold it to Cliffe and went back to the States.

So much for the pioneers and old-timers of 1862.

* * * * *

Born in Sandwich, Shetland in 1858, Eric Duncan joined his uncles in the Comox district at the age of 19 and farmed at Sandwick, today part of Courtenay. He served several public offices as noted, including 23 years as postmaster, a position that introduced him to all in the community.

He’s described as a prolific writer because of the many letters, poems and articles he submitted to newspapers and magazines in the Canada, the United Kingdom and the U.S. The modest home he shared in Sandwick with wife Anna Ask is on the Canadian Register of Historic Places.

Their adopted son Charles (Pritchard) Duncan was killed in the First World War.