Steamboat Mountain - Tale of Three Cities

Overnight, progress and prosperity came to Steamboat Mountain and environs, with not one but three township springing up where, but weeks before had been virgin wilderness...

Few British Columbia will have heard of Steamboat Mountain. Yet, a century and a-quarter ago, it was the site of the richest gold strike in provincial history.

At least, such was the claim made for it by its promoters. Alas, when the bubble burst, thousands were heartbroken to find that this latest El Dorado was just a myth—a gold rush that existed only in the minds of two American confidence men!

This First Nations family was lucky—they weren’t among the many who sought their fortune on Steamboat Mountain. —BC Archives

The story behind the rush to Steamboat Mountain (now Mount Shawatum) is as intriguing as the way in which this hummock of stone in south-central British Columbia won its first name. According to legend, it was christened back in the days when Port Hope was a Hudson's Bay Co. Fur trading post. As late as 1858, the isolated fort, some 80 miles up the Fraser from what was to become New Westminster, remained far off the beaten track, its only visitors the annual fur brigades, company officials and neighbouring Indigenous peoples, all of whom travelled overland and by canoe.

Until the arrival of the first steamboat, Fort Hope was completely isolated. That changed overnight with the reports of a fabulously rich gold strike on nearby Steamboat Mountain. —The Canadian Encyclopedia

Thus it came with some surprise to officers of the fort, early in June of that year, when Natives informed them that they’d observed great puffs of white smoke rising from the river like smoke signals. Although he found it hard to believe, the post factor, a man named Walker, concluded that the strange smoke must have been from a steamboat attempting to beat its way upriver. Due to the fact that the river below the fort arched in a horseshoe and formed a strong current, Walker knew that any visiting steamer would be sometime in arriving.

The following day the little Surprise puffed into view, whistle blowing, crew cheering.

But, much to the crew’s amazement, those at the fort greeted them with polite restraint. The Surprise hadn’t lived up to her name and the steamboat’s captain was mystified by the reception until Walker grinned that all of the fort’s inhabitants had known of the vessel’s impending arrival 24 hours in advance; their cool reception was a joke.

With that, all present marked the historic event with cheers and whoops. Hours later, the Sea Bird moored off the fort, and Hope’s link to the outside world by riverboat was forged. With this development, Steamboat Mountain appeared on the maps, a name which was, half a century after, to make headlines across the continent.

Actually, there’s another legend concerning the christening of Steamboat Mountain.

According to this source, what’s now known as Mount Shawatum was originally named after two prospectors named W.L. Wood and James Corrigan. Apparently, the two built a raft with which to navigate the Skagit River as far as their claim on Ruby Creek, a tributary. For reasons lost to history, Wood and Corrigan christened their raft ‘Steamboat,’ and its place of launching became known locally as Steamboat Landing.

Whatever the case, the Steamboat Mountain area slept peacefully until the 1880s when British Columbia's golden treasury drew more and more prospectors to the area. Gold wasn’t to be found in paying quantities, however, with the result that, after the initial interest, Steamboat Mountain was allowed to rest on disturbed—until 1910, when two American miners, Dan Greenwald and W. A. Stevens, reported a fabulously rich discovery on the mountain slopes.

They had, they said, been tipped off to a previously unreported rich strike by a dying prospector in Nevada, and had travelled to B.C. to see for themselves.

This is what drew 1000s of fortune seekers to creeks such as those on Steamboat Mountain. These bottles are filled with gold nuggets! —BC Archives

The result of their survey was a wild stampede to Steamboat Mountain as the first 100s, upon hearing of the newest El Dorado, poured into the area by riverboat, on horseback and on foot. The rush gained momentum when respected Vancouver mining promoter C.D. Rand announced that he’d “acquired substantial interest in the discovered claim... that development work on the mine would proceed during the winter months and a stamp-mill was planned for the following year."

Jumping onto the bandwagon, Hope newspapers heralded the strike as a genuine El Dorado, reached by following the “trail of the gods,” this heavenly goat track more or less following what’s now the busy Hope-Princeton Highway to Mile 120, before turning south along the Skagit River to a point within a few miles of the American Border.

Overnight, progress and prosperity came to Steamboat Mountain and environs, with not one, but three townships springing up where, but weeks before, had been virgin wilderness.

Although small enough by today's standards, each of the “towns” boasted a store and the inevitable saloons, as well as sundry other buildings and residences (many of these tents). With mining and real estate promoters working around the clock to promote the area as B.C.’s latest Mecca for the enterprising and adventurous, more and more people—and more and more money—flowed into the region.

Why not a rush to Steamboat Mountain? After all, B.C. had known really rich gold strikes before—Barkerville was proof of that. —BC Archives

All were convinced that this was the biggest strike since the Klondike.

Typical of the of that halcyon era, the new communities—Steamboat, Steamboat Mountain and Steamboat City—vied for supremacy, each proclaiming itself to be the capital of the new goldfields.

Messrs. Stevens and Greenwald, not unnaturally, enjoyed immense popularity. Whenever they arrived in Hope, it was to a reception such as usually reserved for royalty. Crowds turned out to cheer, and the beaming prospectors turned promoters basked in the glory of their discovery.

By the spring of 1911, the rush to Steamboat Mountain had swelled into a wave of humanity, and the competing communities of Steamboat, Steamboat Mountain and Steamboat City became household words throughout the Pacific Northwest.

Unfortunately, due to their similarity of names, confusion began to grow among those farther afield; a problem that the News tried to eliminate by designating the townsites by their hotels. Thus, the three settlements became in, turn, McIntyre and Raymond's Hotel; Still and Raymond's Hotel; and the Jarvis Hotel. The former hostelry proudly announced itself as the "Steamboat with buildings,” although the promotional releases prepared by hotelier Jarvis weren't far behind with their glowing descriptions of the aerial tramways and double-track railways leading from the mines.

Of the three communities, Steamboat was the first to form a Board of Trade under the guiding hand of David Sloan, to act as city council and to oversee the “care of sanitation, fire protection, street paving and lighting;” in short, all of the modern conveniences. Not to be outdone, the leading citizens of Steamboat Mountain advertised their mines as being richer than those of Ontario's famous producers at Porcupine.

Think placer mining for gold is easy? Look at all those boulders! —BC Archives

The satellite communities of Chilliwack, Hope and Princeton weren't slow to discern the potential of the proximity to the new diggings and soon began to herald themselves as gateways to Steamboat Mountain.

But only Hope enjoyed the talents of Harvey P. Leonard, who poetically penned that it would soon become famous for it skyscrapers and be linked to the Canadian Northern Railway. Business continued to boom with something like seven companies being incorporated, with as many as many millions in capital, to search for the Golden Fleece of Steamboat Mountain.

When winter snows brought a halt to further development, most of those involved settled back to await spring thaw, sure that, with the snow gone, they’d strike it rich. Those who’d already staked their claims on likely looking creeks throughout the vicinity undoubtedly felt the most confident as it was rumoured that, come spring, at least 5,000 more gold seekers would be on the scene.

Every rock, every pebble, every grain of sand has been washed and sorted by hand—with no guarantee of a pay cheque at the end of the day. —Vancouver City Archives

The more optimistic of those taking part in the stampede were open to possibilities of silver, platinum, copper, lead and zinc existing in the immediate locality. For that matter, a geologist named Camsell went so far as to report the discovery of diamonds on nearby all Olivine Mountain.

Finally, it was spring, and the diggings roared to life with renewed energy. Steamboat City now boasted its own newspaper, the Steamboat Nugget, edited by R.J. Clark. Among the newcomers was the well-known “Alaska Jack” Ginnin, who opined that, after mining throughout the continent, he’d never seen more likely looking prospects than those of Steamboat Mountain.

But—ever so vaguely at first—an undercurrent of confusion began to manifest itself throughout the various camps. More and more, questions were being asked by old hands and newcomers alike. Questions such as: where was the gold?

Amazingly, all of the excitement, all of the commotion and all of the optimism hadn't turned up so much as one single rich strike!

Slowly, then with greater urgency, word began to spread that there was something seriously wrong on Steamboat Mountain. For all of the glowing reports made to date, no one other than Messrs. Greenwald and Stevens seem to have found anything beyond “colour.” Finally, mining entrepreneur Rand, head of Steamboat Gold Mining Co. Ltd., became worried enough to call upon the partners at their mine—to be turned away by an armed guard.

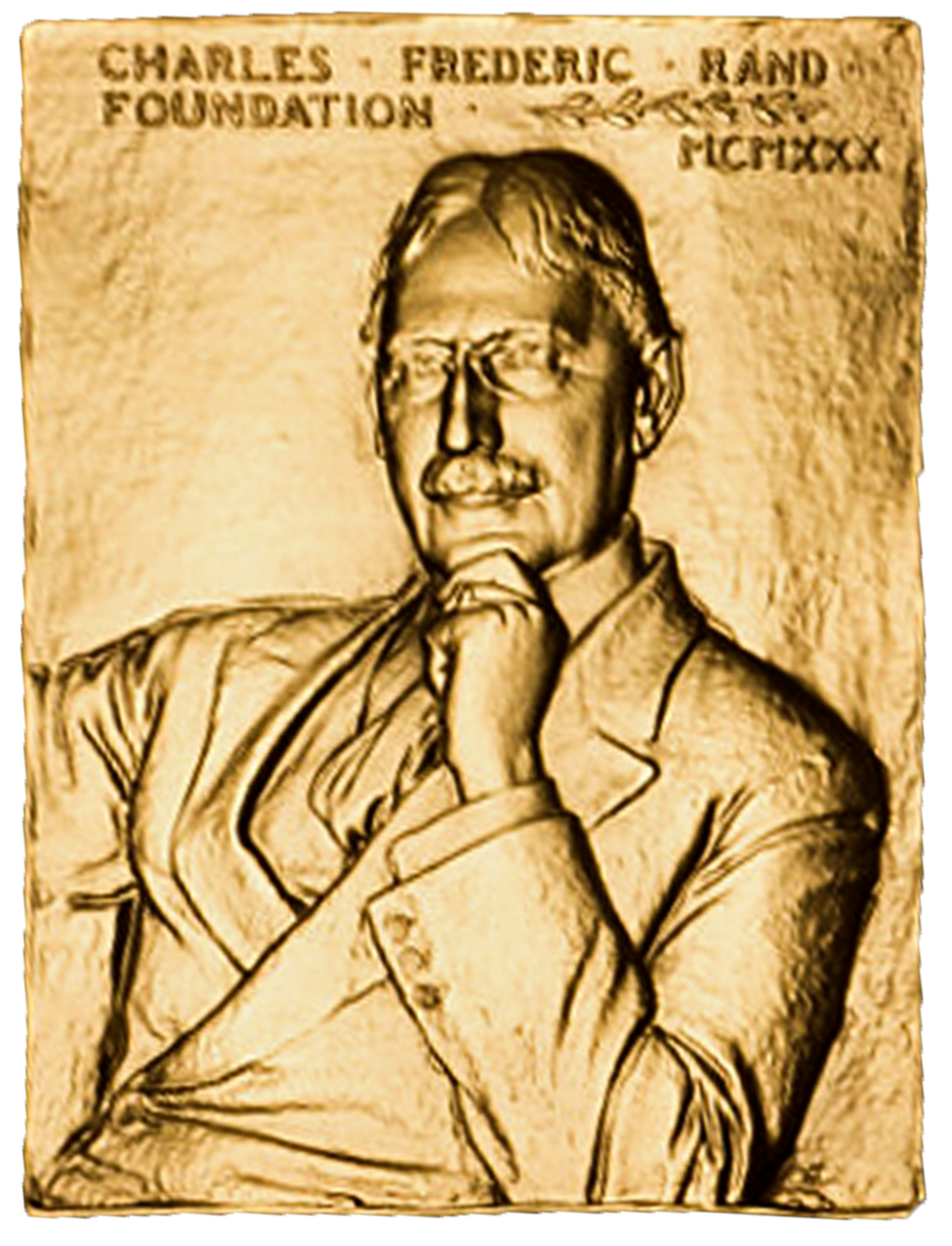

American mining engineer Charles F. Rand was no one’s fool. This gold medal issued by by the American Institute of Mining, Metallurgical, and Petroleum Engineers bears his likeness: “The Charles F. Rand Memorial Gold Medal was established in 1932 and is awarded for distinguished achievement in mining administration, including metallurgy and petroleum. Charles F. Rand was President of the Institute in 1913 and Treasurer from 1922 to 1927. Rand was a developer of mines and new processes in iron mining. He was President of several mining companies.”

—American Institute of Mining, Metallurgical, and Petroleum Engineers

Now alarmed, Rand waited until nightfall and attempted to sneak inside for a look, only to be discovered and again ordered off the property.

By then it was July, and the questions—by now accusations—were flying thick and fast. When someone at last admitted aloud that he hadn't seen any real gold since he arrived, someone else remarked they hadn't seen Greenwald or Stevens for some time either!

With this observation, panic swept Steamboat Mountain and Steamboat City. It didn't take long to discover that the partners had secretly disposed of their holdings for good sums and had vanished. Greenwald later turned up in South America then New York, Stevens popping back into the public view in California.

Several professional mining engineers were brought in to verify or to debunk the value of various claims—particularly those of Greenwald and Stevens. All were negative but couched their findings diplomatically.

W.A. Lewis gave his opinion of the Steamboat Mountain diggings, based upon two months of on-the-ground research, with both barrels:

“There’s nothing there, never was, and never will be. It was all a fake. All the gold samples that were brought out from there were from Tonapah and Cripple Creek [Nevada].”

Others suggested that the Americans had salted their claims by hack-sawing gold coins into fragments, loading them into shotguns and peppering the rocks with high-grade “ore,” courtesy of the United States Mint. To the uninitiated (and to many who should have known better), this was a sure-fire method of turning worthless rock into a gold mine.

Sadly, it was all over.

The golden dreams of Steamboat Mountain were nothing more than empty air and, disheartened, the thousands of fortune hunters turned sadly homeward, or moved on to newer, more promising fields.

Within months, the three little townsites were virtually deserted. By this time the evil Mr. Greenwald appears to have thought all had been forgiven, or at least forgotten, and returned to New York. There, playing to the hilt the role of the successful mining promoter, he was interviewed by a newspaper reporter. Piously, he told his interviewer how much he hated those “wicked men who lure poor miners to worthless ground by sending out false reports[!]"

Upon the interview being picked up by Canadian newspapers, the West Yale Review grimly noted, “Dan's nerve food is a success.” Greenwald then seems to have dropped out of sight.

As for ex-partner Stevens, things didn't go as well. Upon losing his ill-gotten gains in another mining venture in California, the destitute and despondent swindler committed suicide.

The years passed, and Steamboat Mountain’s short-lived gold rush became another memory. Then even its name was changed. Camp poet laureate Leonard has left us this wistful tribute to the brief glory that was Steamboat Mountain’s, 125-odd years ago:

Take me down, down

Where the Steamboat trail goes

There we’ll bury our Sorrows

Our cares and our woes.

Get a claim while you can

And the diggings are new

If you linger long, all you'll get is a view.

Instead of the rain we’ve the real ‘Mountain Dew’

Down where the Steamboat Trail goes.