Editorially speaking…

Instead of my usual catch-all of contemporary news with historical roots, a sidebar, so to speak, to this week’s post on once-infamous Ripple Rock.

Seymour Narrows and ‘Old Rip,’ as will be seen, were the most feared navigational hazards in British Columbia waters—indeed, on the entire Pacific Coast. For more than three-quarters of a century they posed a double threat, one visible, one unseen, to life and limb.

On a lesser scale, they created traffic jams by forcing ships, large and small, to wait for a favourable tide before proceeding north or south. The cost of this navigational inconvenience alone justified the Rock’s partial destruction by explosives—the greatest non-nuclear blast in history until that time.

But it took several efforts, several lives, millions of dollars and years of brilliant and heroic effort to achieve what remains as one of the most remarkable engineering feats in Canadian history.

One of the ships that came to grief in Seymour Narrows was the warship, USS Saranac, in June 1875.

* * * * *

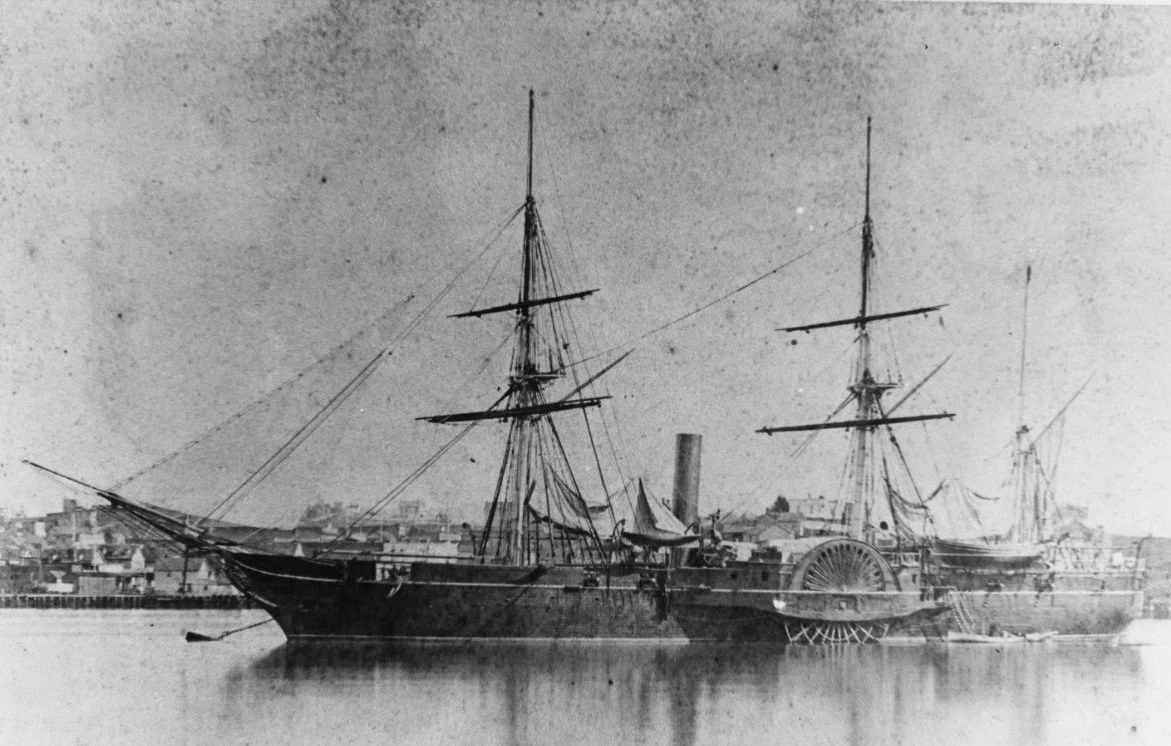

The paddlewheel steamship USS Saranac. Her engines couldn’t match the incredible force of notorious Seymour Narrows. —Wikipedia

“The fearful rushing water as it closed over her was so powerful that it would have killed any living being who might have been aboard..."

The loss, in a matter of minutes, of the USS Saranac was one of the more spectacular of the 1000s of British Columbia shipwrecks over the past two-plus centuries. ‘Saranc,’ Indigenous American for “the river that flows under rock," inspired the naming of this 13 gun sidewheeler. In 1862, Captain George Richard, Royal Navy hydrographer, applied it to Clayoquot Sound’s Saranac Island—in honour of the Civil War sloop rather than the disappearing river.

Some 13 years later, the object of this compliment met her fate in Seymour Narrows. Not, as some have noted, as Ripple Rock’s first shipwreck, but certainly one of its more conspicuous casualties. Under the command of Capt. W.W. Queen, Alaska-bound Saranac cleared San Francisco on June 8th, 1875.

Her mission was anything but warlike, the small three-master gunboat (at 2100 tons, small by today’s standards although her company numbered 173), was serving as a floating laboratory for Smithsonian Institute scientists in quest of ‘natural curiosities’ for the forthcoming Philadelphia Centennial Exposition.

In the Campbell Rivers Museum is the journal of a young seaman who was on board Saranac on her last voyage. Presented by Charles Sadilek’s granddaughter, it describes, in the Yugoslavian immigrant’s neat hand, how the steam-powered sloop coaled at Nanaimo then, with Capt. William George as pilot, proceeded up the Inside Passage.

(Sadileck thought Nanaimo to be prettily situated but too wet for his taste, it having rained intermittently through their stop-over there—“altogether too much when it is kept up almost the year round”. Sadileck’s information about annual precipitation obviously didn't come from the Chamber of Commerce.)

Saranac sailed “on what is called a fine day,” the young seamen continued, ruefully, "a patch of blue about as large as a postage stamp may be seen overhead, but that does not signify that the rain is over..."

Rain or no, all went well until the 18th when the ship entered the southern approaches to Seymour Narrows and the twin underwater peaks known singularly as Ripple Rock. Capt. George had taken many ships through these swift narrows between Vancouver and Quadra islands and he advised Capt. Queen to wait for flood tide before proceeding.

But, overruled by the Saranac’s master, George called for full steam ahead, for maximum manoeuvrability once into the rapids. Seaman Sadilek enjoyed an unobstructed view of the unfolding tragedy:

"...In the midst of the whirlpool, the ship refused to answer her helm and was for a moment beaten about by the angry waters. All of a sudden there came a crash [that] shook the ship as if it had been fired into [by] a battery of guns".

Saranac struck the ‘The Rock’ with such force at 14 knots that every man aboard was thrown to the deck and she heeled so far over that it was feared she must capsize. With a last gasp her engines drove her towards Vancouver Island and her anchors and a hawser were thrown out to secure her to the shore.

Mere minutes had elapsed since she struck but, already, Saranac was sinking.

Some men leaped to shore, most took to the boats. "... Hardly had we got away to a safe distance,” wrote Sadilek, than "the combined pressure of the rising water in the hold and the air started to tear away the upper deck with all its weight of guns. But only for a moment, for the next instant the ship commenced to sink under the water stern first and it was a brief moment before she disappeared entirely.

“The fearful rush of water as it closed over her was so powerful that it would have killed any living being who might have been aboard."

Saranac’s company had watched her go in stunned silence. Then, as loosened spars shot to the surface, "cheer upon cheer rose up in the air... It seemed like losing a friend whom we had not properly cherished until [she] was leaving us forever..."

Although it was high tide, which lessened the current to some extent, for some of the crew it was all they could do to make it to land safely, so ferocious are these rapids.

Charles never forgot Seymour Narrows. He’d “never seen an inland body of water more threatening than Seymour Narrows. Even the ocean in a tempest has no such ravenous aspect.”

Their hardship wasn't ended. By evening they were so exhausted as to be “quite indifferent to our fate, and had the boat capsized it would have been doubtful if any of us would have made any great effort to save ourselves..."

Four days after USS Saranac’s sinking her company were picked up and taken to Esquimalt. There were no casualties.

That’s how powerful are the tidal currents of Seymour Narrows.

Today, cruise liners regularly ply the Inside Passage and navigate Seymour Narrows as a matter of course. This hardly would be the case if ‘Old Rip,’ as the larger of the underwater mountain peaks was unaffectionately known, still lurked within 20 feet of the surface.

* * * * *

I’ve seen this photo of downtown Duncan’s Quamichan Hotel many times; I’ve used it many times. But to see it in full colour thanks to the colourization and resolution skills of Nigel Robertson is to see it anew.

The handsome Quamichan Hotel on Duncan Ave., Duncan, as it likely looked in 1895. It and the Tzouhalem across the railway tracks were the city’s leading hotels in the long ago. Duncan also had the Alderlea Hotel, known as the “loggers’ and miners’ resort”—a horse of a totally different colour! —Nigel Robertson