The Killer That Was Ripple Rock

Probably few of the 1000s of commercial and pleasure craft annually plying British Columbia waters have much fear of navigating Seymour Narrows.

True, this 2500-foot-channel between Vancouver, Maud and Quadra islands is still hazardous.

But, within living memory, this was the dreaded lair of the worst marine hazard of the entire West Coast—Ripple Rock.

An aerial view gives only a sense of the incredible tidal surge that’s Seymour Narrows. So powerful that it could stop ships in their tracks! Compound this with the danger of Ripple Rock’s twin fangs immediately below the surface and it’s little wonder that vessels of all kinds and sizes came to grief here for more than three-quarters of a century. —Wikipedia, Maj. J.S. Matthews collection, Vancouver City Archives

100s—that’s 100s—of vessels, large and small, came to grief here.

Removal of the threat Ripple Rock, one of the great engineering feats in Canadian history, involved many years, millions of dollars and several lives.

* * * * *

Prior to the epic blast of April 5, 1958, ‘Old Rip’ was a “submerged, steeply sided mountain situated approximately in the middle of Seymour Narrows. The bulk...is well below the water’s surface at low tide, but two pinnacles situated about 410 feet apart in a north-south line reach upward to menace passing ships.

“The north peak section is approximately 160 feet wide by 360 feet long and the south peak is approximately 150 feet wide by 200 feet long. At low tide the tip of the north peak is only about nine feet below the surface and the south peak is approximately 19 feet down."

The dangers of Ripple Rock were well known to early mariners. An 1886 B.C. Pilot, published by the British Admiralty, recommended vessels “enter at or near slack water and keep the eastern shore aboard in order to avoid Ripple Rock. Vessels steaming at the rate of 12 knots have been unable to make headway and even to be set back, while attempting the Narrows during spring tides."

Thought to be first to safely navigate the Narrows where tidal changes can form 17 mile-an-hour currents, was Capt. George Vancouver. But many ships and small craft in following years have not been as lucky. First victims were the American gunboats USS Saranac and Wachusett.

Sananac met her grim end on June 15th, 1875, when transitting the Narrows, then known as Euclataw Rapids, at an uncontrollable speed of 14 knots. Unable to answer her helm in the giant eddies, Saranac was swept over the main peak, which gutted her. When the last longboat left her buckling sides, she slipped to 60 fathoms, a total loss. Other ships followed....

Apparently “no complete record of losses has been compiled, but it is estimated (in 1956) that since 1875, some 14 large ships have been lost or severely damaged and that more than 100 smaller vessels, fishing boats, tugs and yachts have been sunk with the loss of approximately 114 lives."

The CPR ‘Princesses’ Ena, Maquinna and Mary, the CNR ‘Princes’ George and Rupert, and the CCGS William J. Stewart are among the better known ships to have encountered difficulty here.

The Canadian Coast Guard’s hydrographic ship William J. Stewart became victim to Ripple Rock, in 1944. Incredibly, she was salvaged and returned to service until finally retired in 1979. Even then she wasn’t quite done, serving for years as a floating fishing resort in Ucluelet.—BC Archives

Seymour Narrows provided another, in economic terms, greater headache. Due to its fierce tides, ships were forced to await slack water which occurs but twice a day. Consequently, ships lined up “like cars on Main Street waiting for the green light. At the right moment they dart through from each end, causing a heavy traffic which, in itself, is far from desirable in such a restricted passage.

“The yearly loss to ships forced to lie idle for long periods add up to millions of hours with consequent costs and dollars."

First to express interest in removing the infamous Rock came, surprisingly, not from a Canadian agency, but from the United States Army Engineers. The American cable ship Burnside, en route to Alaska, had narrowly escaped being sunk in the formidable Narrows, and the chief of engineers suggested “some understanding might be reached with the Canadian government looking to its removal in the interest of shipping..."

This acute observation eventually reached Ottawa after passing through American, British and, finally, Canadian channels. The American report then seems to have been ‘filed’—meaning it hasn’t seen the light of day since.

Unfortunately, Ripple Rock couldn’t be filed away and forgotten. During the next 37 years, Seymour Narrows claimed victim after victim, capsizings, collisions and strandings becoming almost commonplace. One reasonably accurate record of mishaps, 1875-1974, lists 27 ships, smaller craft and barges. In 1931, the government went so far as to have a commission investigate the possibilities of removing the menace.

The provincial capital’s strange argument was an old one, dating back to the days of Confederation. Ripple Rock offered the only natural foundation on which a bridge could be constructed to finally, truly unite Vancouver Island with the rest of the province. (A story in itself.)

As the controversy raged, the issue became one of landlubbers versus mariners. The former favoured retention of the rock cap until it was possible to build a causeway. Sailors were equally adamant. The Rock had to go—and what was the matter with these lunatics, wanting to compound the threat by building a bridge on top!

The commission favoured the latter and weighed different proposals as to how to do the job. Five plans were examined, four of which were rejected as being “impracticable, too expensive,” or too dangerous. Ironically, the theory deemed too expensive was the one ultimately employed and which proved successful.

The best plan, said the commission, as it was "inexpensive and promising success,” was to drill and blast the Rock from a floating platform. The estimated cost $167,000.

The public again joined in the act, forwarding several unique proposals, including a Royal Canadian Navy attack with bombs and torpedoes. Even though years began to pass without any concrete action, the suggestions continued to come. One dreamer, keeping up with the times, favoured dropping an atomic bomb. (This does’t sound too impractical when one recalls that the U.S. government gave serious thought to using “clean” nuclear devices in mammoth engineering projects.

The initial attempt to actually remove, or at least reduce, the bottleneck came in 1942. The new interest in such an ambitious undertaking resulted from the Second World War, then raging; both the Canadian and American governments were anxious to have the vital Inside Passage clear for shipping.

First of all they had to do convince a contracting firm. When no bids were forthcoming, two companies suggested a ‘cost-plus’ arrangement. Awarded the contact, the B.C. Bridge and Dredging Co. began the monumental task by building a complete working model of Seymour Narrows and its underwater monster, including the floating plant with which they intended to perform the job.

Tests finished, a special 150-foot-long drilling barge was constructed and towed to the site. Six concrete anchors, some weighing 250 tons each, were sunk in either shore and heavy steel cables run across—no mean achievement in itself. The barge was secured to the cables and held over the Rock, to serve as a platform for drilling operations. The plan was to pepper the underwater mountain with holes and fill them with explosives.

Drilling was about to begin when the cables, vibrating uncontrollably in the riptide, "snapped like threads!”

Throughout the summer of 1943, workers struggled desperately to anchor the barge. Despite their every effort, the cables continued to break—roughly one every second day.

Work was suspended for the winter, and it wasn’t until the summer of 1945 that another attempt was made. Again, a barge was to be held over the Rock by cables; cables that were 3500 feet long and weighed 10 tons a piece. But this time, instead of being submerged and the victims of treacherous tides, they were strung overhead.

Once again, the barge was successfully installed and drilling began.

Winning this preliminary bout was another remarkable achievement of the contractors. However, by autumn, only a pitiful eight percent of the required holes had been bored—at a cost in access of $1 million. Faced with financial disaster, without any guarantee of success, Ottawa dropped the project. This decision was influenced by the drowning of nine workers when their small boat capsized in the frenzied Narrows.

Another eight years passed with mariners still urging the Rock’s removal.

In 1953 the National Research Council accepted the challenge. When the herculean task of obtaining ore samples from the seabed was completed, the answer became apparent. Not only were the rock formations the same as those encountered every day by miners but, better still, the sea didn't leak into the test holes.

Thus, tunnelling under the Narrows from Maud Island and up through the Rock itself, which had been suggested—and rejected—25 years earlier, was the solution. Seven hundred and 50 tons of high explosive would provide Old Rip’s farewell.

Work began in 1955 with a main shaft more than one-half-mile-long being painstakingly carved from Maud Island. None of the tragedy which had broken the back of the wartime scheme plagued this operation, work progressing smoothly but for labour difficulties.

When miners reached the Rock, ‘raises’ were extended upward to each peak. Then ‘coyote drifts’ and ‘boxhole’ entries were carved out of Rip’s belly. These would hold the special explosive, Nitromex 2H, two years in the developing specifically for this task. The amount to be used had been increased by 1,375 tons—theoretically sufficient to “raise the 390,000-ton Empire State Building one mile straight up!”

But the blast had to be neat as well as powerful. Engineers were “required to sheer off mountains that were underwater and throw the rocks so precisely that no dredging would be necessary. The rock must not only be shattered but must also be aimed to fall into submerged holes in the waterway. To let it fly at random would mean dredging it out again; to let it settle back in the same place would not solve the problem.

Quite an order!

As zero hour approached, the RCMP took extensive precautions. Scientists had determined that a danger zone of three-mile radius would be created. This area included a safety margin but the Mounties carefully checked the entire circle, evacuating 65 persons, their pets and livestock.

This was the easier part of the officers’ job, for they knew that some individuals would risk “having their heads blown off for the sake of a front-side view of the blast”.

Dozens of old logging roads and trails were barred and as the momentous event drew near, B.C. Forest Service units supplemented RCMP mobile communication trucks. Roadblocks were installed and five RCMP patrol craft and two RCA F crash boats assumed stations at each entrance to the Narrows. An RCMP plane would be on hand to rush any injured to hospital.

But the Mounties’ greatest headache promised to be a record traffic jam on the Island Highway near Campbell River. Newspapers, radio and television had given the project such immense publicity that it was expected many would seek front row seats. However, this problem was solved by using the same news media: announcements pointed out that the blast could be delayed by adverse weather and the public would find it much more comfortable to watch it on their TV screens.

As the last hours ticked away, fears were expressed as to the damage to be caused by the largest non-nuclear, peacetime explosion in history.

Campbell River feared that the man-made earthquake would crack two nearby dams. A pulp milk only six miles from the blast was anxious about its 200-foot smokestack. If the engineers trying to alleviate these fears didn't sound too convincing to some, that was because they weren't all that sure themselves just what the blast would do!

The explosion would be triggered from a bunker, just 700 yards away, on Quadra Island. By dawn, April 5th, all technicians were at their posts although the weather caused anxiety. The leaden sky dimmed hopes. Favouring them, however, were southerly winds and high cloud level. These conditions were essential to clear away resulting gases.

While the clock entered its final circuit, the observation bunkers filled with more than 200 guests, mostly newsmen and photographers. On hand were Lieutenant Governor Frank Ross, the federal minister of Public Works and his deputy, and the top officers of Western Canada's armed forces.

Zero hour was 9:31 a.m, timed so that northern tides would carry debris and gases into isolated waters. Sixteen minutes before the blast, the sky had so darkened as to indicate postponement. Then the first rocket was fired—the order was “Go!”

“.. Three... Two... One... 0! " came the countdown, which had been delayed two minutes by an aircraft entering the danger zone.

A moment passed quietly as 5.3 miles of fuse flashed at the rate of 21,000 feet per second. Suddenly the green water became a surging white as a great bubble rushed to the surface. Sky vanished behind a flower-shaped smudge of rock and water that soared higher and higher, reaching an awesome 1,000 feet.

Top: The first sign of the incredible upward surge of water and debris. Bottom: One of the most famous photos ever taken: the Ripple Rock explosion.—By Lett, Sherwood (1895-1964) - [1], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=68393624

A monstrous, living thing—350,000 tons of rock fragments, 370,000 tons of water—the artichoke broadened, streaking toward the island shores at two miles per minute. The 2,750,000 pounds of Nitromex, detonating in a split-second chain reaction, continued for long seconds—an eternity to the speechless observers.

Shock waves slammed into rocky shores, again, without damage.

As the blast gradually subsided, the spectators’ main anxiety was the result of 30 months of work at a cost of $3 million. Was Ripple Rock impotent at last?

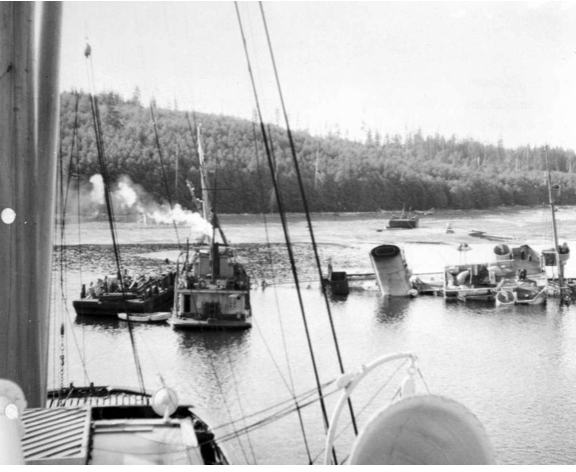

The RCMP Patrol Vessel Victoria and consort Nanaimo were the first to navigate Seymour Narrows after the historic blast. —www.flickr.com

To find out, RCMP boat Victoria with Lieutenant Governor Ross and guests aboard, slowly approached the Narrows. From the south came RCMP Nanaimo. The patrol vessels neared, then passed each other... It’s ironic that the first vessel to steam over Ripple Rock was named after Victoria, the city that had so much to say in its defence.

The enormous surgery was a complete success—at least 40 feet had been amputated from Old Rip’s twin peaks. The feared damage from the blast’s shock waves never materialized, one of the greatest undertakings in Canadian history had been finished to perfection.

After 83 years of shipwreck, death and maritime inconvenience, Ripple Rock’s fangs had been pulled.