Terror On the Tracks - Head-On Collision at Ladysmith

(Part 1)

“I’ve written a book.”

This statement, from almost anyone else, would have been no outrageous thing in itself. I heard if often when wearing my publisher-printer hat.

But from this humble man of the soil who’d told me in previous conversations that he’d had but Grade 3 formal education...!

What would possess him to begin such an undertaking? That old myth of self-publishing, ‘vanity’? Dreams of writing the Great Canadian Novel?

The answer proved to be much much deeper. There was neither ego nor ambition at work here. The man had a story to tell, one that had driven him since childhood; hence his very personal, almost simplistic, but meaningful title, A Story To Be Told.

I’ve told a few stories myself over the years. But in all my historical meanderings, I think this one is unique and among the most poignant and intriguing of them all.

* * * * *

From such a generic title readers learn little from the cover of this modest book of only 64 pages. The artist’s illustrations shows an oncoming steam locomotive on a curve of track—you have to look twice to see that a second train is headed in the opposite direction, on the same track.

It’s in the late Bob Dougan’s dedication that the first real hint comes that four men lost their lives in the wreck of Engine No. 1, north of Ladysmith, on Sept. 11, 1900: Robert Fisher, Superintendent of Alexandra Mines [sic]; Samuel Walton, engineer; Hugh Thomson, fireman; Henry Saunders, brakeman.

Nathan Dougan, left. —Bob Dougan photo.

The story begins more than 30 years before, with the arrival at Cobble Hill of James and Annie Dougan. They worked hard to carve a successful farm from what was rain forest and, 10 years later, their seventh child was born. According to his own son, Robert, Nathan Paul “inherited much of the Irish temperament, easygoing most of the time, argumentative when in the mood, and very serious about life in general. He was inclined to trust others too quickly, I sometimes felt.

“He was never cut out to be mechanic [work with his hands] but he was a good student; he loved a good book and never seemed to tire of the delightful pastime of reading and good literature.”

Nathan’s first job on the farm began at the age of six, driving the milk cows out to pasture on neighbouring Thain’s farm in the morning before school, and fetching them for milking in the afternoon.

As he grew, so grew his responsibilities on the farm and, at age 14, he finished school to work full time at home.

He didn’t stop studying, however, dedicating most of his evenings to reading good books. It’s likely because of this that he became a good conversationalist and undoubtedly it contributed to his later recording much of the area’s history in the Cowichan Leader; son Bob later compiled these into what became a highly readable and much sought-after book, Cowichan My Valley.

Likely, too, Nathan’s reading made him increasingly restless. This at a time when the world about him—even out-of-the-way Cobble Hill—was dramatically changing.

Completion of the E&N Railway had sparked the founding of Cobble Hill Village just a mile from the Dougan farm which, situated on the southwestern slopes overlooking what would become Dougan Lake, had but a short time before been been wilderness. One could now travel to Victoria or Nanaimo in just a few hours instead of having to hike the Malahat.

There was a bigger world than that of the Dougan farm, for all its acres, and Nathan decided that he wanted more from life than the daily drudgery of the family homestead.

One day in 1895 he threw a pack over his shoulder and with just a few dollars in his pocket—and without so much as a goodbye to his mother and father—headed for Seattle where three of his brothers had already established themselves.

Or so he thought.

Upon arrival he found that not only were his brothers unemployed, but so was much of the male populace. It was an inauspicious start in the real world and, down to the last of his money and with no prospects of finding work, Nathan had no choice but to return home.

From Victoria he hiked over the Malahat to a farm at Hillbank where he was hired to cut cord wood for 50 cents a day and board although he had to cook his own meals. Years later he would tell his son that this, his first real job off the farm, was hard work and less fare.

But it was his guilty conscience that bothered him most. Here he was, within two miles of home and he hadn’t called upon his parents, so embarrassed was he to face them. It took a family friend to convince him to swallow his pride.,

His father, ever the stern patriarch, showed no emotion; his mother’s restrained demeanour told him better than words how badly he’d hurt her by his unannounced departure.

Nathan went back to working on the farm. But he knew he couldn’t stay. There had to be more to life than this, for him. He was determined to find it.

* * * * *

I never met Nathan Dougan even though I moved to within five properties of his son Bob’s acreage in 1974 (which is how I came to know Bob). It’s one of my smaller regrets. I’m sure I’d have liked Nathan as I did Bob. I know I’d have been—I am now—respectful of his well-earned mantle that he and the late Jack Fleetwood) share as senior Cowichan Valley historian/storytellers.

We’d have been neighbours, Nathan Paul Dougan and I. But he of the well-known pioneering Cobble Hill family passed away three years before I bought property at Cherry Point, five years before I moved from Saanich. Happily, I did get to know Bob (and brother Fred who lived just up the street from me); it’s through Bob that I came to learn the story behind A Story To Be Told.

As we’ve seen, with his love of literature Nathan wasn’t meant to be a man of the soil. After the failed attempt to find work in Seattle and his shame-faced return home, this young man who, as a boy, had run from his first encounter with a train, resolved to work on the railway like his brother Isaac who, in Bob’s words, was only too willing to instruct him in telegraphy. Thus equipped, Nathan found a job as telegrapher and weighman for the Alexandra Mine in South Welllington.

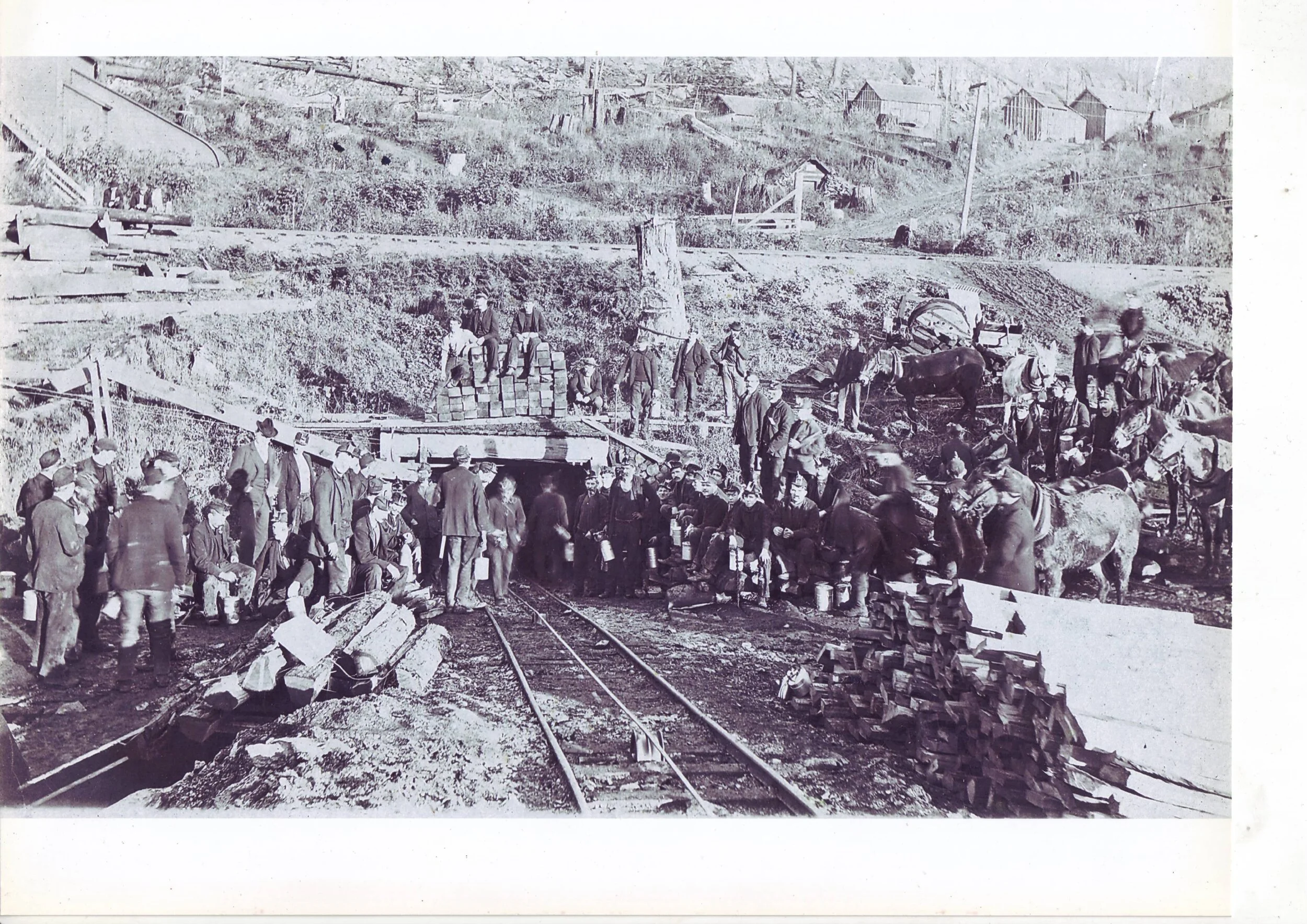

The Alexandra Mine at South Wellington where Nathan Dougan had his first job as telegrapher and weighman. —Tom Teer photo.

He was to weigh the loaded coal cars and to manage the telegraph office. The latter was by far the easier task, the position of weighman placing him in a state of constant conflict between the manager and the miners; the former for not wanting them to be accredited too much for their coal, the latter for being convinced they weren’t allowed enough.

This no-win situation drove him to seek employment elsewhere. In the fall of 1898 after teaching a Cumberland druggist to operate the telegraph there, Nathan moved to Oyster Harbour where James Dunsmuir was building the new town of Ladysmith.

The new Extension Colliery was underway as were the deep sea bunkers and wharves, and the din of pounding hammers and rasping saws was heard from first till last light of day. Because of litigation with a competing colliery over a right-of-way, Dunsmuir had shelved his original plan to ship coal via his established Departure Bay wharf facility and ordered construction of a shortline railway from Extension to Oyster Harbour. It joined the mainline E&N Railway at Fiddick’s Junction, South Wellington.

In a 1954 article published in the Ladysmith-Chemainus Chronicle Nathan recalled his arrival in Ladysmith and his being set up as telegrapher-dispatcher in an old rail car which served as both his office and his “abode”. “My telegraph call, ‘AR,’ I took from the word car; wonder if it is still the same.

“For some time my job was a sinecure; wiring for timber and building supplies and assisting Mr. Bugslag with the time-keeping kept me but lightly occupied; even when coal commenced and long were the hours, it was not an onerous job...”

But the pace picked up and kept Nathan on his toes. Besides being telegrapher he was now train dispatcher, ticket agent, expressman and purchasing officer. As a conversion, his office-abode, an old passenger car whose rich oak interior recalled its better days, worked well enough but for the fact that its small windows limited his view of the rail yard. His peripheral view of the mainline track, north and south, was quite restricted.

This was a critical matter. While being briefed on his duties, it had been impressed upon him that he was to “read those engine numbers correctly. Do not at any time identify engines by appearance. Read your orders carefully and hand them directly to the conductor who is in charge of the waiting train.”

But how could he do this when he could hardly see the tracks? Visibility was even worse if he was working in the freight shed. Upon the approach of a train he’d have to drop everything, return to his office window, note the passing locomotive’s number and wire Fred Brown, head dispatcher in Victoria, who’d authorize the coal train to proceed onto the E&N mainline. Dougan would pass this order, in writing, to the conductor.

Crude as it was, this system worked. But as the new Extension mines began shipping and rail traffic increased, the lack of a bay window became more problematic. Colliery locomotives No. 1, No. 7 and No. 10 came and went several times a day, there was increasing traffic on the mainline, and smaller yard engines shunted cars about the yard and to the harbourside bunkers at all hours.

As if this weren’t enough, the colliery added a new engine—a second No. 1—to its roster!

“It was to be a yard engine,” son Bob wrote more than 80 years later, “which was quite within the rules, but in order to do its shunting of the loaded and empty coal cars for both docks, it had to travel on a portion of the E&N mainline. At least 3000 feet of mainline would be used, which meant that the engine would be travelling on tracks past the dispatcher’s office most of the working day. My father found this confusing and asked his boss why they did not give this engine another number.”

It didn’t require another number, he was told; after all, it was different in appearance from the others and in due course a new dispatcher’s office—one with a big bay window—would be built for him. He must be patient. Till then, “Be careful and keep things moving.”

Also domiciled in the telegraph-dispatch car was “a hard-bitten old railroad man”. Hugh Lutes, who bossed the Chinese section gang and who’d learned the ropes during construction of the CPR under the legendary Andrew Onderdonk, was an ardent fan of Liberal leader Wilfred Laurier. He was also a heavy drinker: “Lutes could imbibe an enormous amount of whisky... Indeed, he was so thoroughly infused with alcohol that I truly believe, were he exhumed, he would be found as natural as life...”

Lutes strongly disagreed with the way things were being run. He was waiting for a reply to a wire one day when a train passed the office. Normally taciturn and hungover, on this day he was garrulous enough to say that the various locomotives, yard, colliery and mainline, “should have their own distinct numbers,” that there shouldn’t be two No. 1’s. Also, he insisted, it was essential that Dougan see the front of those engines, so as to be able to check those numbers.

“It’s dead wrong, Dougan. One of these days when you’re busy you could make a mistake, and report the wrong locomotive. They will blame you, Dougan. A collision between two engines is a terrible thing; it is always fatal to the engineer and fireman.”

His parting words were, “Make a mistake, young Dougan, and you’ll never forget it!”

Nevertheless, as Nathan would tell Bob years later, he hiked his job and “didn’t want to complain my way out of it”.

As it happened, after Saturday morning, Sept. 15, 1900, he’d have the rest of his life to regret not having spoken up...

The original water colour by artist Lloyd Witham as he perceived the last moments before the Nos. 1 and 10 met head-on north of Ladysmith.

I’m going to intrude here. In April I revisited the old Diamond Yard north of Ladysmith. It’s situated just beyond the TCH overpass, on the left (west) side. The E&N mainline, the very stretch of line that ‘s the stage for Nathan Dougan’s story, parallels the highway but it and the former marshalling yard are hard to see from the highway if you’re paying attention to your driving; you’re best to access the Diamond area by coming in the back way past the hospital and the Ladysmith cemetery.

There’s absolutely nothing today to show that, a century ago, these few level acres of scrub trees were the site of the second busiest railway yard on the Island. Even two-three years ago you could find rusted tie plates and spikes littering the ground that gave a hint of the past, but no more.

In short, even if you know your Ladysmith or Island railway history, you have to stretch your imagination to mentally view this flatland, with its overwhelming noise of passing traffic, as a busy rail yard. Here, seven days a week, small steam engines shunted loaded and empty cars about, passenger and freight trains came and went on the mainline—the mainline they shared with loaded and empty coal trains, coming and going from South Wellington.

That’s where, at Fiddick’s Junction, immediately south of the old No. 10 Mine at Beck Lake, South Wellington, a once crucial switch shunted coal trains onto and off the mainline from the colliery railway.

At Fiddick’s, as at the Diamond Yard, there’s nothing today to even suggest its historical significance, just an abandoned grade leading off the mainline and now severed by a massive gravel pit. Just two sandstone bridge piers in the Nanaimo River serve as its memorial.

(To be continued)

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.