Terror On the Tracks - Head-On Collision North of Ladysmith

(Part 2)

You won’t find this in Bob Dougan’s book, A Story To Be Told. It’s something he told me personally; of growing up on the family farm on Telegraph Road, Cobble Hill, and of knowing ever so vaguely, even as a child, that there was a skeleton in the family closet.

Whispers, sometimes, between adults, and hints, even smirks, from his schoolmates—but nothing substantial, nothing he could really grasp in his young mind: just something sinister in his father’s past...

There was more to it than that. Every so often when he was very young and playing in the yard with his brothers and sisters, a big man in a big car (as both seemed to small children who seldom saw either one, close-up) would sometimes visit his father. Nathan Paul Dougan would invite him in and the two would talk for hours.

But for days after each visit, Nathan would be quiet, “down” as Bob put it.

So who was the big man in the big car?

It wasn’t until Bob was an adult that his father told him of his short-lived career as a telegrapher-dispatcher for the E&N Railway. A career cut short when Nathan made a fatal mistake and allowed two trains on the same track at the same time and four men died.

Without denying his own culpability, Nathan explained how the railway’s traffic system was also at fault, how improvements were made after the fatal crash and after Nathan was convicted of manslaughter.

And the big man in the big car? He was Nathan’s jailer with whom he’d become friends.

******

On a warm sunny day in March, we go looking for the site of the Ladysmith train wreck. —Photo courtesy of Bill Irvine

“A most distressing train wreck occurred...on the E&N Railway two miles north of Ladysmith,” reported the Duncans Enterprise. “As a result of a collision four men were killed...”

The old railroader’s warning came to pass when the southbound No. 1 engine and 14 loaded coal cars met head-on with the northbound No. 10, with 34 empties, on a blind curve just north of the Diamond Junction switching yard.

(For those readers familiar with the stretch of Island Highway that parallels the E&N tracks north of Ladysmith, we’re talking about the Ivy Green Park area, on the west side of the highway.)

At an estimated impact speed of just under 40 miles per hour (each engine had slowed down slightly from 20 mph because of the curve and slight grade), the smaller No. 1 was sandwiched between its own loaded cars and the heavier No. 10 whose engineer, fireman, a passenger, conductor and brakeman, with just seconds to react, leapt to safety after applying the brakes and throwing the engine into reverse.

Not so engineer Samuel Walton (who also tarried to apply his brakes and switch gears, fireman Hugh Thomson, brakeman Henry Saunders (just two days on the job) and Robert Fisher, superintendent of the Alexandra Mine.

There was a thunderous bang instantly followed by an ear-splitting grinding and twisting of steel as coal cars, loaded and empty, were catapulted into the air or piled atop each other like dominoes gone mad. Tons of coal, dust and shattered train parts rained from the air.

Once everything had settled, there was brief, stunned silence. Somewhere in the midst of the carnage were the mangled remains of Walton, Thomson, Saunders and Fisher.

(Almost two years to the day before, another Dunsmuir coal train had plunged into the Trent River when the Union Colliery trestle collapsed, killing seven crewmen and passengers. The No. 1’s fireman Hugh Thomson was supposed to have been on that train and undoubtedly would have been killed; he used to say how lucky he’d been “not to take that train out”.)

Joseph Hunter, the E&N’s general superintendent, was on his way north on other business when he was informed by telegraph of the accident. He was soon on the site and, once the bodies were recovered (all but one of Thomson’s legs), overseeing 100 men in clearing away the debris and laying down new track to bypass the wreckage so that the mainline service might be restored.

Victoria for permission to “run engine No. 10 north. On being asked if engine No. 1 had arrived from the north, he replied that it had. This, as it afterwards proved...was when the grave error was made...”

Two graphic views of the wreckage of the No.’s 1 and 10. From Victoria and Nanaimo, special excursion trains were pressed into service to carry curiosity seekers to the disaster scene.—Bob Dougan photos

“My father, Nathan Paul Dougan, made a mistake in reporting E&N No. 1 on a spur leading to one of the bunkers for unloading at Ladysmith,” Bob Dougan wrote in his 1986 study of the tragedy, A Story To Be Told, “when in fact it was on its way from Wellington with a number of loaded coal cars on order No. 14, issued by Fred Brown, Head Dispatcher in Victoria.

“On receiving the report that E&N No. 1 was in the yard at Ladysmith with its train, Brown telegraphed an order back to Ladysmith, ordering Conductor Thornborough to proceed to Fiddick’s Junction with Engine No. 10. Father told me that he handed the order promptly to Conductor Thornborough, who was waiting in [his] office.

“Thornborough [returned] to his train and ordered the engineer to pull onto the mainline to proceed northward.”

Three days after the crash, the Victoria Colonist reported: “As a result of the inquest held here today to inquire into the death of Henry Saunders, one of the victims of the railway accident at Ladysmith on Saturday, Nathan Paul Dougan, the operator at Ladysmith, was committed for trial on a charge of manslaughter, the coroner’s jury ruling that the accident was due to his negligence.”

For the four men of the No. 1, instant death. For their families and friends, grief and irreparable loss. For young Nathan Dougan a lifetime of regret.

* * * * *

Two trains on the same track and four men dead: It was a railway man’s worst nightmare come true.

At the inquest for brakeman Henry Saunders, the E&N’s Chief Dispatcher Fred Brown, who had 35 years’ experience as a telegrapher and dispatcher, testified, “Engine No. 1 was reported [to me] to be in the clear at Ladysmith inside the yard limits...and the operator asked me for orders for No. 10, which [I] immediately gave without further question.” He identified the operator as Dougan and declared “there could be no mistake” in his [Brown’s] taking the message that No. 1 was in the Ladysmith yard.

Last to take the witness stand, Dougan acknowledged that he’d received Brown’s order to dispatch the No. 10 to Fiddick’s Junction. Asked why he’d informed Brown that the southbound No., 1 was in, he said, “I believed her to be in.”

Coroner: “What reason had you for believing her to be in?’’

Dougan: “I cannot state what reason I had, except that I believed her to be in.”

Coroner: “Did you see her?”

Dougan: “I did not.”

The jury ruled that Saunders died Sept. 15, 1900 in the collision of coal trains No. 1 and 10, the accident being the result of “negligence of Nathan Paul Dougan in reporting the arrival of train No. 1 at Ladysmith to the [Victoria] train dispatcher when it had not arrived”.

Dougan, who, it was said, appeared not to understand his situation, was taken before magistrate Yarwood who committed him to trial for manslaughter.

Son Bob noted that Deputy Coroner Stanton’s questions had been to the point, the answer giving by his father, brief. However, while the Colonist’s coverage of the inquest had been detailed, even verbatim, its account of the trial, which began on October 11th, is “somewhat brief...with no statements from the witnesses for the Crown or the defence”.

Given the sensational circumstances of the tragedy, the Victoria daily’s coverage—all of two paragraphs—is extraordinarily muted. Why? Could it be because it was owned by James Dunsmuir?

Eighty years after the Ladysmith tragedy, Bob, who’d grown up in a family in which there were some things one didn’t talk about, set out to learn the whole story. With the help of Thomas Lines, well known Cowichan Valley barrister, he obtained a transcript of the trial. This in itself was was something of a challenge as many records have been lost or destroyed over the years. As luck would have it, a transcript was found. Written in an obsolete form of shorthand, it defied Bob’s attempts at deciphering it until he enlisted the help of the late Ladysmith historian Viola Cull and her niece, Mrs. J. Kenny.

H.K. Prior testified that he’d hired Dougan two years before, his duties being to “report trains, see to freight, and telegraph the arrival of trains [at Ladysmith] to...the head dispatcher in Victoria... It was [Dougan’s duty] to satisfy himself that the mainline was clear...before requesting permission for a conductor to take another train out on the main line.” Prior had a book of rules, didn’t know if Dougan had one. The Ladysmith yard was very busy. The E&N had “only” one No. 1 engine the Wellington Colliery “some little engines”.

Chief Dispatcher Fred Brown outlined routine procedure, described Dougan as a “fair operator” whom he’d interviewed for the job. “I did not point out his duties under the regulations. I had used him before at Wellington. I know his capabilities.”

He detailed the last, fatal communications between Victoria and Ladysmith on the morning of the 15th.

“If I had got an order from the operator that [No. 1] had left [South] Wellington at 10:00, I would not have issued my order and probably the accident would not have happened...

“There is no loose system on my line. I worked on CPR. They kept a train register [but he didn’t]. I accept word of [the] operator and don’t check back on him...” The Nos. 1 and 10, referred to as specials because they were Wellington Colliery rather than E&N ‘regular’ trains, usually operated between Ladysmith and South Wellington on a first-come first-served basis, their comings and goings being monitored by the Ladysmith dispatcher.

Look closely at this side view of the No. 1—Dispatcher Dougan would have had only a glimpse of her as she passed by his office. Do you see any identifying numbers? —Bob Dougan photo

It was a conductor’s duty to report to the dispatcher upon arrival but he was given considerable latitude—“if he reports inside of an hour or half an hour, it is the custom. The rule was for the conductor to report when he was ready [to go].” The colliery and three mainline engines didn’t, in his mind, require “any special checks for this small number of trains”.

“We [the E&N] have only one [No. 1] engine. The Colliery have a [No. 1] engine but I give no orders to her unless she comes on my line. On 15 September she was in Ladysmith, a dead engine.”

Albert Bostock, conductor and survivor of the No. 1 who’d been riding in the caboose and had jumped to safety, described the horrific crash.

Eight years on the railway, he had a rule book but didn’t know if other employees had copies as they were “not any too numerous”. He didn’t think there were enough to go around, Supt. Prior having told him “they had run out,” but “I never heard complaints of their absence. I don’t think I heard any complaints of the way the line was run. I was satisfied.”

He’d never heard Dougan complain about his job or safety or operating conditions.

Conductor of the No. 10, Joseph Thornborough, stated that the No. 1”was not there on my arrival” at Ladysmith. “I have known other days when [No. 1] did not run to Ladysmith. I have left Ladysmith before [No. 1] even came down.”

Head dispatcher Brown had testified that the No. 10’s conductor shouldn’t have applied for clearance if he knew the No. 1 wasn’t in the yard. Nevertheless, armed with Dougan’s 10:02 a.m. order, Thornborough headed north at 10:12 and “met [No. 1] about one and one-half miles from Ladysmith.”

It was Dougan’s responsibility, he said, to step out of his office and “see for himself if the [No. 1] train was in.”

All said and done, but for those so tragically involved, it was a funny way to run a railway.

* * * * *

They say that hindsight is 20-20 vision, Looking back from the vantage point of more than a century, with the sworn testimonies of those involved to ponder, the marvel is not that Ladysmith had its head-on collision between locomotives No. 1 and No. 10, but that it took so long to occur.

As far as the Crown was concerned, it was all the fault of Wellington Collieries’ dispatcher Nathan Dougan for clearing the No. 10 for Fiddick’s Junction in the belief that the No. 1 was in the Ladysmith yard. There was a No. 1 in the yard, sitting idle. It was one of two engines bearing the same number—but it was not the southbound coal train.

At Dougan’s trial for manslaughter Conductor Thornborough testified that he’d asked Dougan for permission to return to Fiddick’s in full awareness that No. 1 “was not there [Ladysmith] when I arrived.” Previously, the E&N’s chief dispatcher had stated that he shouldn’t have done so without verifying the No. 1’s position.

Thornborough had the complicity of senior engineer Frederick Bland: ”We knew [No. 1] was at South Wellington when we passed and that she had not arrived [Ladysmith]. Thought she was not in the way... I saw the driver of [No. 1] at South Wellington. He shook his head at me and I took it as a notice that he was not leaving and when I got orders to proceed, I was satisfied.”

Dougan couldn’t check with his South Wellington counterpart, Frank Pelky, because the telegraphist-dispatcher wasn’t at his station that morning. He was hitching a ride to Ladysmith on the No. 1!

Not a single witness was called in Dougan’s defence although Isaac Sowerby, Vancouver station agent with 17 years’ experience including dispatching came close. After describing the double-order system used on the Mainland whereby the movement of two trains sharing the same track were plotted, he said, “I have often known an operator [dispatcher] to say train in, and it was not there...

“Just before the train arrives, operator very busy and he is liable to make mistakes.” Nevertheless, he thought “it would be duty of a train operator to verify his report” before informing the Victoria dispatcher that the mainline was clear.

Last to take the stand, Dougan swore that he’d never had a rule book, that he’d had “no instructions whatever,” thereby contradicting the chief dispatcher’s clam to having examined him for the position two years before. He explained that he couldn’t see up or down the tracks, only a train as it passed by, because even his new office (built to replace the original converted passenger car) lacked a bay window.

There were no windows in the freight shed. On 15 September, “Conductor [Thornborough] came and asked for orders...about time [No. 1] was due. Saw a train passing station. I was very busy about my different duties. I naturally believed it was the No. 1 as it was her time of arrival and when [Thornborough] asked for orders to Fiddick’s Junction, that confirmed my belief... I did not guess, I actually believed it was [No. 1].”

He listed his other duties besides those of dispatcher and telegraph operator: recording all coal shipments, checking, weighing, loading and unloading freight, selling tickets, janitoring and “custom work as well” (sic). In the previous four months 150 buildings had been erected in Ladysmith and “all materials came through my station”.

He confirmed Conductor Thornborough’s testimony that the No. 10 had—more than once—proceeded onto the mainline without waiting for the No. 1 to report in. It was done, in fact, with Victoria’s knowledge: “If [No. 10] went out when [No. 1] was not in, I was generally told by the conductor or [chief dispatcher].”

On the fatal morning, “I was not told by Conductor Thornborough [No. 1] was not in.”

Three hours after retiring to consider their verdict with a copy of the railway’s rule book, the jury returned with a verdict of guilty, a strong recommendation for mercy and a firm reprimand for Dougan’s employers: “From evidence submitted...we beg to advise that the present system of train dispatching and signalling of trains in use on the E&N Railway could be greatly improved, and so ensure greater safety to the travelling public, as well as to employees on the roads. We would suggest that this matter be brought to the attention of the Provincial Government.”

(Shortly afterwards, Wellington Colliery locomotives were renumbered so as not to conflict with E&N engines.)

Judge Drake held Nathan Dougan to be wholly accountable; despite his having many other duties to perform, it was up to him to go about those duties, “notwithstanding people coming about”.

But he accepted the recommendation for mercy in sentencing him to nine months in prison.

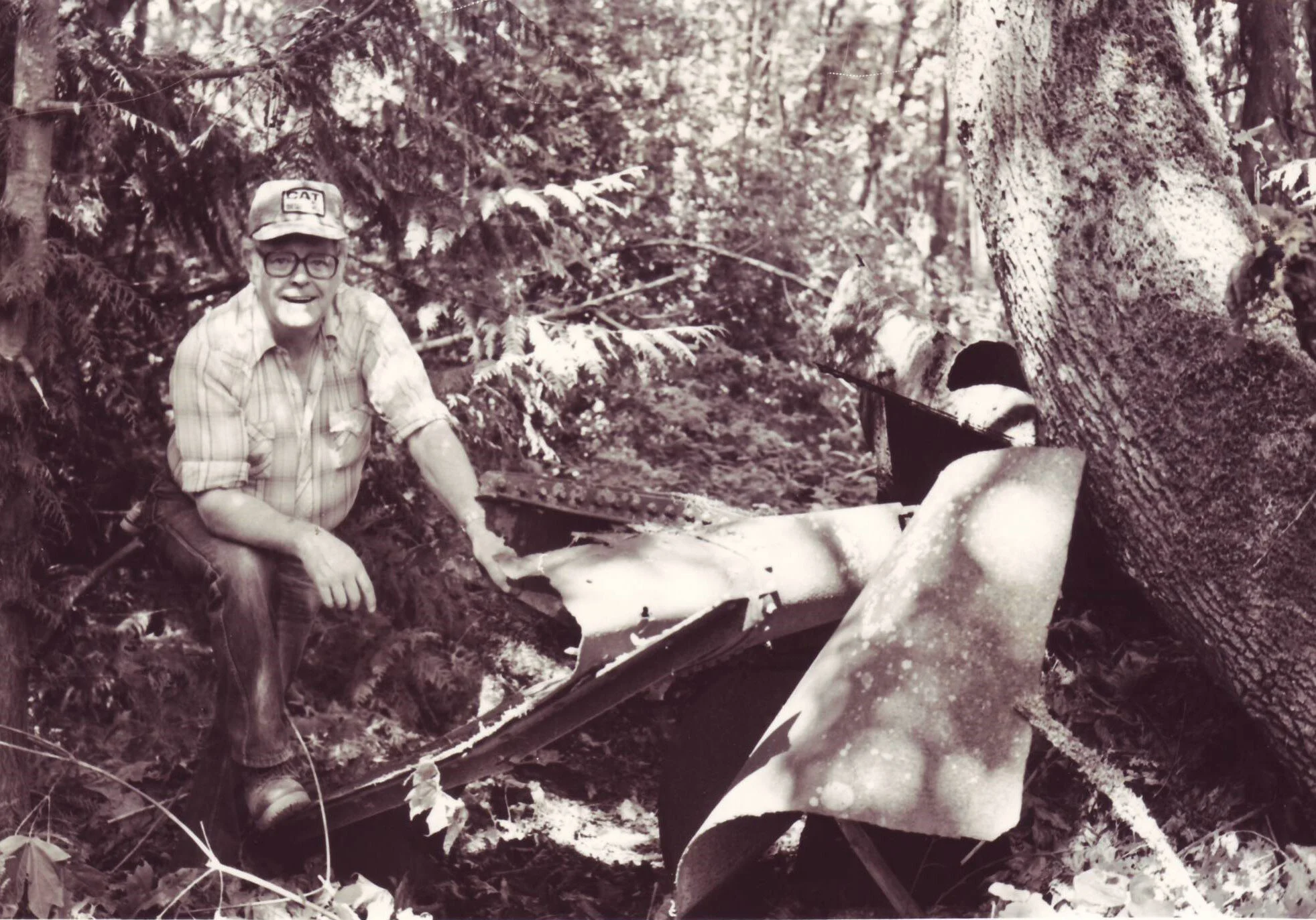

In 1986 Victoria railway historian Patrick Hind examined the wreckage of a tender of one of the two colliery trains involved in the Ladysmith disaster. —Author’s Collection

“My father never claimed to be totally innocent of blame for the terrible accident that took the lives of those men,” son Bob wrote 80 years later. “He always felt, however, that the mine company, Wellington Collieries, and the E&N’s management should have realized that the system in use, for identifying and dispatching of trains, consisted of a lot of guesswork. In his opinion, the train crews, who were engineers and conductors, and therefore more experienced in traffic control, should have, for their own safety, put pressure on the Wellington Collieries to renumber their locomotives.”

It seems obvious that they should have pressed for safer operating procedures, period. To think that, according to testimony by other railway employees, it wasn’tt unusual for the No. 10 to pull out of Ladysmith in full knowledge that the No. 1 hadn’t arrived—!

It’s also undeniable fact that both the E&N Railway and Wellington Collieries were owned by James Dunsmuir, the richest and most powerful man in the province, who couldn’t have been pleased with the adverse attention.

According to Bob, although some family members gave a different number, Nathan served seven months. But it wasn’t hard time, his father having told him that he did errands about the jail, served meals to the chain gang from a chuck wagon, and spent much of the time in the home of his jailer, Vern Stewart, nephew of the Nanaimo police chief, where he chopped firewood and looked after the garden. He and Stewart became friends.

After having several short-term jobs, Nathan returned to Cowichan, married Robina Colvin and began a family on 70 acres subdivided from his grandfather’s farm. The young man who’d sought to escape farming, first by reading then by working for the railway, was back on the land to stay.

Always fascinated by local history, and having known so many pioneer families, for almost 20 years he wrote for the Cowichan Leader. In the early 1970s Bob published many of these articles in book form and Cowichan My Valley, although long out of print, clearly demonstrates Nathan Paul Dougan’s affection for the men and women who’d laboured so hard to make their homes in the Valley.

Bob’s own book, A Story To Be Told, also out of print, is a minor classic in its own right. More than that, it’s an expression of love for his father whose story, long a deep, dark family secret, he set out to learn in the 1980s.

Bob had no desire to whitewash his father, he told me, only to understand. He and Nathan had discussed the tragedy in later year, the rest he’d learned through the newspaper accounts and the trial transcript. That research, such as it is, must stand.

But it seems evident that Nathan Dougan and the crew of the ill-fated No. 1 were victims of shoddy operating procedure that must surely have led to disaster, if not on Sept. 15, 1900, then on some other day.

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.