The Case of the Haunted Man

In last week’s Chronicle we saw how Frank Hulbert aka Frank Pepler appears to have gotten away with murdering 15-year-old Molly Justice in 1943.

He ended his life as a recluse, living in a converted bus. According to his obituary he died “peacefully,” 53 years later.

Which begets the question, Did he suffer remorse? In other words, did Hulbert’s conscience trouble him in later years—or not?

We’ll never know.

Pioneer Victoria was the last stop for many a man on the run... —Sun Life Insurance

But there are case histories of men who—so it’s surmised—were driven to the brink of despair, even self destruction, by the inner demon of a guilty conscience. A century and a-half or so ago, Victoria City Police detective John George Taylor was convinced he was on the trail of just such a man.

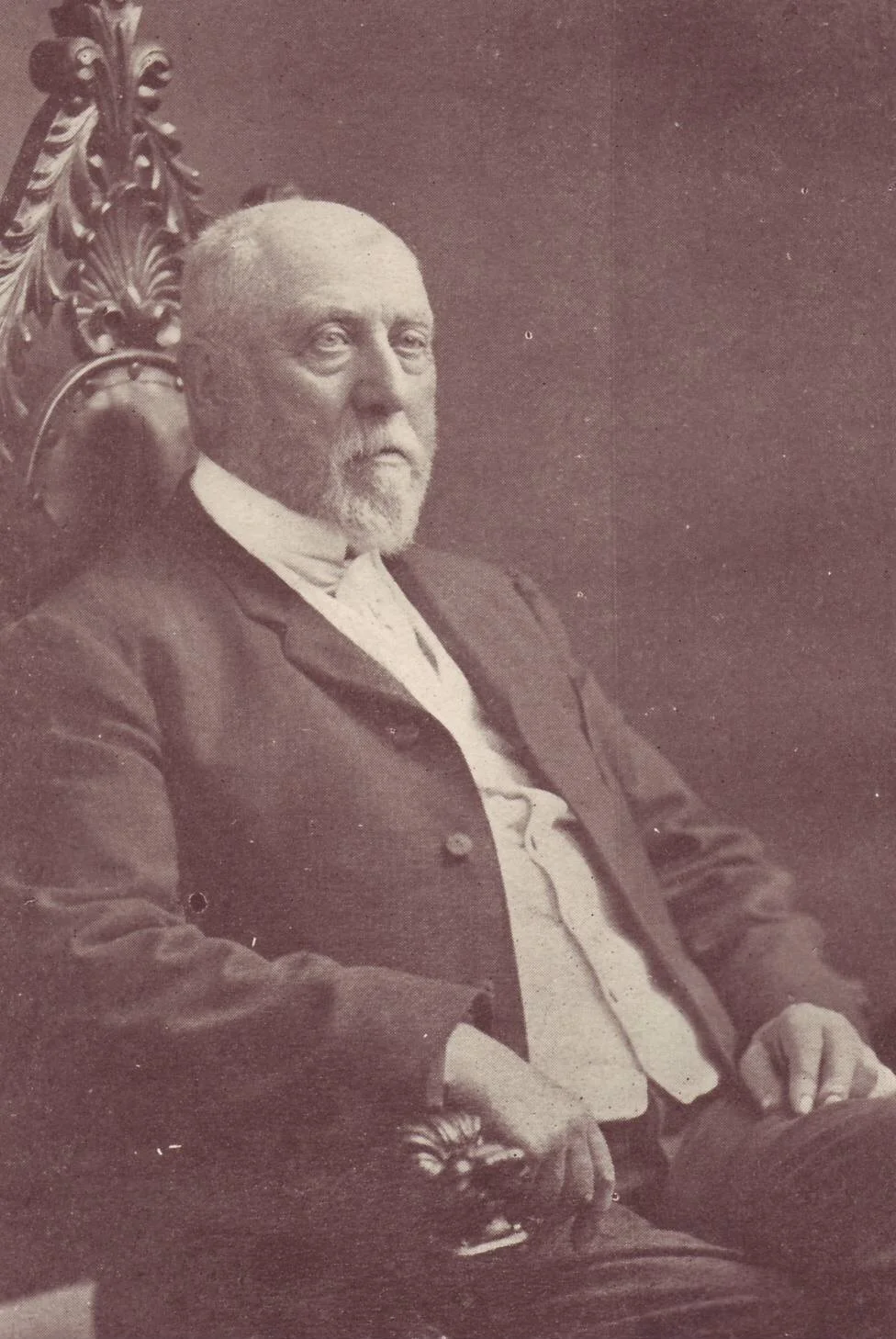

Once again we’re indebted to pioneer chronicler D.W. Higgins whose half-century-long careers as a journalist and politician gave him an inside pass to many of the most newsworthy and historically significant events and characters of his day.

Fortunately for posterity, upon retirement, he recorded some of the best stories in a series of newspaper articles and two books. Here, slightly condensed, is one of his most fascinating tales, ‘The Haunted Man.’

* * * * *

Yes, his prose can be somewhat florid by today’s standards—but D.W. Higgins is one of B.C.’s greatest storytellers of all. —Author’s Collection

The circumstances I am about to relate occurred in the year 1861. The facts were known to a few who lived here at the time; but I believe that with the exception of myself there is not now a living person who was cognizant of the extraordinary combination of events which I intend now to put into print for the first time.

Nearly every old resident knew John George Taylor. He was alive as late as 1891 and his bones lie at Ross Bay [Cemetery]. He was an Irishman and came here from Australia in in 1859. He had been a miner, a rebel, a constable and a member of the Gold Escort in that colony and possessed remarkable detective instincts.

He was one of the most intelligent men who ever joined the Victoria police force, and being strong and fearless, resourceful, and keen-witted as a razor-blade, he was generally selected to inquire into involved cases that required a mind of more than ordinary capacity to unravel.

I do not think I ever met a man whose judgment upon all matters connected with the discharge of a constable’s duties could be so implicitly relied on as Taylor’s...

Taylor brought some money here, and during the 15 years he remained on the force added to it by means known only to detectives and their patrons, so that when he died he had the tidy sum of $30,000 [three-quarters of a million dollars today—TW].

...One night Detective Taylor came to my office and told me that he had watched a strangely-acting man for some weeks, off and on, and had been unable to find out the slightest thing about him.

“And yet,” he said, “the man acts as if he had committed a murder some time in the past. In fact, he’s haunted!”

“What!” asked I, “you surely don’t believe in such things as ghosts?”

“Well, no,” he replied, “I don’t; but that man thinks he is haunted, and I think he is, too. He imagines that he is followed by a child. He fancies he hears the patter, patter of little feet on the sidewalk, and sometimes thinks he hears the rustle of a dress as if some woman were walking by his side.”

“Do you hear them, too?” I asked.

“No, I never hear a thing; and yet the poor soul while I am with him, hears the fall of the feet and the swish of the dress and starts and trembles and breaks into a cold sweat. I don’t believe he ever sleeps—at least not at night. I meet him at all hours walking swiftly along the street with his head bent and his eyes fixed on the ground.

“At first I thought he was a burglar and tracked him, but he never stopped anywhere or did anything—just walked all night. Towards morning he goes to his room in the Fort Street Chambers and does not appear again till nightfall.

“I often engage him in conversation. He is mighty intelligent and has been a great traveller. He’ll talk until he hears the patter of the little feet and the swish of the gown and then he’ll start off like the wind. He’s been somebody some day, but he’s crazy now or next door to it.”

“I say, Taylor, I’d like to get acquainted with that man. If I can’t see a ghost I’d like to do the next best thing—talk with a man who has seen one.”

Popular historian John Adams has made a successful career of giving ‘haunted’ tours of Victoria. I don’t think he’s ever told the tale of D.W. Higgins’s ‘Haunted Man.’ —Author’s photo

There was at that time on Yates Street a place called the Fashion Hotel; it was the resort of the young men of the day... It was arranged that Taylor should steer the haunted man into the Fashion on a certain night, and that i should meet them there as if by accident.

The arrangement was carried out. I was introduced as Mr. Smithers and the man’s name as given to me was Cole. He was really very presentable and chatted away like a man who had seen the world.

He seemed quite sensible. We smoked and drank and conversed for an hour on different subjects, and finally we separated without his having given the slightest evidence that he was haunted or that he was other than a staid, respectable gentleman enjoying a quiet evening with friends.

About two o’clock the next morning, when on my way to my room in Ring’s Hotel, I almost ran against my new acquaintance. He stood by the side of an awning post and I just managed to make him out by the feeble gleam from a street lamp.

“Halloa!” I exclaimed, “you’re out late.”

“Yes,” he replied, “but I’m not the only one. There are others who are out late, too.”

I thought he referred to me, so I laughed as I told him that my profession required me to keep late hours.

“Oh, I don’t mean you,” he rejoined; “I refer to others.”

Then the story Taylor had told me about the man being dogged by the sound of a child’s footsteps and the rustle of a woman’s dress occurred to me.

A creepy feeling began to run up my spine and my hair acted as if it were about to rise and left my hat from my head.

I wished myself safe in bed and made a sudden movement to open the street door and ascend the stairs, when the lunatic, murderer, or whatever he was, laid a strong hand on my shoulder.

“Hold!” he said. “Stay with me—please.”

“No,” i replied as calmly as I could, “I must go to bed. I am sleepy and tired.”

Without noticing what i said, the man retained his hold on my arm and hoarsely whispered:

“Did you hear it?”

“Hear what?” I demanded, as I tried in vain to throw off his grip.

“That—that child walking! Listen to the patter of its footsteps! Surely you can hear it. Listen!”

I listened but heard nothing and so told the man.

“By heavens!” he shouted. You are deceiving me. Everyone tells me the same. You do hear it. You must hear it. Everyone lies!”

I struggled to free myself and succeeded; but he grasped me again. Then I realized that i was in the hands of a stronger man than myself. Again I struggled and again I succeeded in freeing myself. I started for the stairs, hoping to avoid him. By a strange fatality the latch of the door, which was always supposed to be held back by a catch, to allow roomers coming late to bed without arousing the household, was sprung and the door was fastened tight.

I turned and faced the man, making a feint as if to draw a weapon. To my surprise he calmed down instantly, and instead of an aggressive attitude he assumed a pleading tone.

“Forgive me,” he said, “I was excited. I thought you must have heard what I always hear—night and day—morning, noon and night. No matter where I am they are always with me—the soft patter, patter of a child’s feet and the rustle, rustle of a woman’s dress.

“I hear them now—I hear them always, if i lie down or stand up. I have gone 1000 feet below the earth’s crust in a mine and the sounds were there. I have ascended 2000 feet in a hot-air balloon, and all the time the little feet and the gown made themselves heard and felt in the atmosphere.

“Sometimes i fall asleep for a few seconds and then I awake with a start and the sounds break upon my ear and I can sleep no more. It is torture, torture, and it is wearing me out.

“I cannot live much longer—I ought to die, anyhow. I am a lost man.

“I wonder,” he added with a deep touch of pathos in his voice, “if the sounds will follow me beyond the grave...if they will accompany me and like accusing spirits give evidence against me!”

He buried his face in his hands and seemed to weep.

I felt that I could listen no longer. The weird tale of the man, the ferocious air with which he had accosted me, the uncanny hour which he had chosen for the relation of his troubles to me, a stranger, and the feeling that i was unarmed and entirely at the mercy of a madman, if not a murderer, who had fled from the scene of his crime, alarmed me and I knocked loudly on the door for admittance.

Presently I heard a window raised and the rumble of a familiar voice broke like sweet music on my eager ear.

“Who’s dar?” asked the voice.

“Ringo,” I said, “come down and let me in—quick.”

Presently Ringo was heard descending the stairs, and the door was flung back and there stood the landlord on the lowest step. He held a lighted candle high above his head in one hand, while in the other he carried a short club...

“Ringo,” said I, “lend me that club.”

He complied and I turned swiftly around to face my antagonist. To my surprise no one was there. The man had vanished. I listened and failed to hear the faintest sound of retracing footsteps.

“There was a lunatic here who assaulted me.”

The old man came out on the sidewalk with his candle and gazed up and down the road, shook his head, looked at me earnestly for a moment and then asked, with one of his inimitable and never-to-be-forgotten grins, “Have you bin drinkin’?”

“No, Ringo,” I replied, “not a drop.”

“Well, dar ain’t no loo-na-tick har.”

“No,” I said, “he’s run off.”

Ringo shook his head again, chuckled...then with the air of a father admonishing a wayward child, he pointed his fat forefinger at me and said solemnly: “You’d best go to bed and sleep it off.”

...I slept soundly and in the morning told Taylor all about my encounter, and he proposed to “run Cole in...” I begged him to wait awhile and see if we could not find out more about the stranger and his antecedents.

So the hand of justice was stayed.

Several days passed and I saw nothing of Cole. Taylor told me that he had met him nearly every night and that one day, under pretense of wishing to see another man, he had knocked at room No. 4, Fort Street Chambers, and the door was opened by Cole in person. [Taylor] was invited to enter, “and,” said Taylor, “I found everything in order.

“...The room was bright and all the appointments were cleanly. There were nice white sheets on the bed and there was a pretty bedroom set. In one corner a grate fire was burning and at the warm blaze the man cooked his meals. Taken altogether, he’s much better fixed than I am, and I’d hate to have him look into my sleeping quarters after seeing his.”

“Did you find out anything more about him?” I asked.

“Nothing, except that I saw a daguerreotype case on the table. I took it up and opened it, and got a glimpse of a very sweet-looking young woman with a child of about three years of age at her side. I only had a glimpse, because Cole, who was busy at the grate making me a cup of tea, turned quickly around and tore the case from my hands, muttering a word that sounded much like an oath, and put it in his pocket.

He apologized instantly for his rudeness, saying that he had one of his queer turns. He offered no explanation for his singular conduct, but the rest of the time that I was there he shivered like a man with the ague and kept hearing things. I am sure he did because he often looked over his shoulder and twice got up and peered under the bed and table.”

“What do you make of the fellow, anyhow?” I asked.

“I put it up that he’s an escaped murderer from somewhere, that his victims were the woman and child whom I saw in the case, and that it is their ghosts that haunt him.”

I met Cole frequently in the daytime but never again at night. He seemed to avoid the settled part of the town after sundown. I was tempted to call at the Chambers but never yielded to the temptation To be frank, I stood in wholesome dread of the man. I regarded him as a crazy criminal, and I had no fancy for another encounter with an irresponsible person such as he clearly was.

One day Taylor came to me. His eyes were dancing in his head with excitement, and as soon as the door was closed and the rest of the world was shut out my room, he began:

“You know that poor soul, Cole? Well, when I picked up the daguerreotype case in his room, as I told you, I saw ‘Shanklin, daguerreotypist, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S.A.” stamped on the gilt rim that surrounded the pictures. I only caught a glimpse but I remembered the name and address, and I wrote to Shanklin, etc., and told him about seeing the portraits with his name on as maker and asked if he knew the parties. I also described Cole as well as I could.

“Today, I got an answer from Mr. Shanklin telling me that my information is most valuable’ that there have been anxious enquiries made for many months as to the whereabouts of one James Coleman, who disappeared two years before from Pittsburgh; that the portraits are those of his wife and child and that the description I gave of the man answered the description given of James Coleman in a handbill sent out by the police and which I now have.

“Then,” [he] continued, “I have a letter signed by one Tardell, who calls himself Chief of Police, asking me to keep a close watch on Cole and telling me that a party will leave Pittsburgh immediately for Victoria to take him in charge.

“So I have located him at last,” concluded Taylor, “and he shan’t slip through my fingers. He undoubtedly murdered his wife and child and that is why he is haunted by them.

“Do I believe in ghosts? Yes, from this on I am a believer in them. They have brought this wretch to justice, and he will be surely hanged for his crime. No wonder that he hears the footfalls of a child and the wish of a woman’s dress. The scoundrel! I am surprised that their dying cries do not haunt him, too.”

...In those days it required about eight weeks for a person to reach Victoria via Panama and San Francisco from New York, and nearly two months fled before anything more was heard from the East. It was in the month of May that Taylor came to me with a queer look on his usually immobile face and said, “Those parties arrived last night!”

I understood that he meant the parties in quest of Cole. “Yes,” he continued, “and i have arranged to point the man out to them today.”

“The villain [will] be much surprised,” I remarked.

“Yes, indeed,” returned Taylor, “and he’ll not be the only surprised person either. There are others who will be astonished.”

...About four o’clock that afternoon Fort Street was the scene of a very remarkable incident. A tall, dark man was seen to emerge from the Fort Street Chambers and walk rapidly towards Douglas Street. As he neared the corner, Taylor stepped out of a doorway and accosted him. The man shook the detective’s hand warmly. Taylor laid a hand on the other’s arm as if to detain him, and the two engaged in an animated conversation for a few minutes. The detective afterwards described the interview as follows:

“Have you heard from them lately?” he asked.

“Yes, I hear them all the time. Last night and this morning they were worse than ever.”

“How do you account for them?”

“Oh! I don’t know. It must be nervousness.”

“Did you ever do anything wrong—did you ever kill anyone, for instance?”

“No, no, thank God, no!” he returned with fervour, “at least not intentionally, but I know that the woman and child who haunt me are dead and that I murdered them by my ill-conduct.”

Still retaining his hold on the other’s arm, Taylor turned him slowly round till he faced the East and then beckoned to some person who stood within a store...

“Release me!” exclaimed the man, “I must walk on until the end.”

He throws off the detective’s grasp and turns swiftly around, as though preparing to fly from the spot... He utters a cry like a wild animal in pain and falls backward just as a young woman and a little girl advance with streaming eyes and outstretched hands.

“They told me you and Dorothy were dead!” he gasps.

“Jem—husband--have I found you at last? Thank God, I did not die!’ the woman cries. “You were not to blame. It was the work of that wicked woman who led you astray, Jem—dear Jem!--and I forgive everything. Come home and we shall be happy once more. I was very sick, for I loved you all the time, but I felt that some day we should be brought together again. Come, dear, come!”

The man makes a motion as if he would fly; but the woman grasps his hand and implores him to hear her. He pauses...and with the ever-ready Taylor on one side and the woman and the child on the other, suffers himself to be led into a little room at the rear of the store, and there, Taylor said, he left them locked in each other’s arms and shedding tears as if their overcharged hearts would break.

“Do you still believe in ghosts, Taylor?” I asked a day or two afterwards.

“Well, no; not exactly. But I believe in a conscience although I don’t know that I have got one myself. It was remorse that ailed Cole or Coleman. He had deserted his wife and child and was afraid to return or write home. She loved him and paid the Pittsburgh police to hunt him up, for her father has heaps of money.

“His conscience made him a coward and made him hear things. But, by Jove! it took an Australian-Irishman to bring them together again, and my fee was $1,000 which I have got sure enough.”

“Does he still hear things?” I asked.

“Oh, yes, he hears the childish footfalls and the woman’s garments swishing; but he now sees as well as hears the child and the woman and does not fear them any more. They will return home. It was a lucky thing for all concerned that I picked up that daguerreotype case, wasn’t it?”

I acquiesced and the incident was closed when Mr. and Mrs. Coleman and child, united and happy once more, left for home on the next steamer.

* * * * *

Today the Taylor building serves as a seniors independent living facility for the Cridge Centre for the Family. —Courtesy of the Cridge Centre

As we’ve seen, detective John Taylor, who wasn’t sure he had a conscience, was obviously mercenary. The fact remains, he bequeathed his sizable estate to the B.C. Protestant Orphanage, Victoria.