The Cave of Crystals

For years in a previous lifetime I spelunked on weekends. In other words, I and friends explored caves, small, large, often wet and dirty, but sometimes breathtaking.

Horne Lake’s Riverbend Cave is so spectacular it’s now a provincial park. —Author’s Collection

Which probably accounts for my particular interest is this legend of a lost cave as told by Rev. William Henry Collison, one of B.C.’s legendary missionaries among coastal First Nations. He tells the story in his fascinating memoir, In the Wake of the War Canoe (edited and annotated by Charles Lillard).

Born in County Armagh, Ireland in 1847. Collison attended the church missionary college at Islington and the Indian School, Cork. He. married Marion M. Goodwin in 1873, the year in which the Church Missionary Society sent him to Port Simpson to assist William Duncan. He became the first missionary to work on the Queen Charlotte Islands [Haida Gwaii] in 1876.

After receiving holy orders from Bishop Bompas at Metlacatla in 1879, he began working with the Gitxsan on the upper Skeena River. In the early 1890s he and his family moved to Kincolith where he remained, except for brief trips to England, until his death, January 23, 1922.

Which brings us to the story of the Cave of Crystals, as told to Collison by an old chief whom he’d known for many years, and whom he’d “been privileged to lead from heathenism into the light of the truth”. The chief’s story, related two years before his death, struck Collison as being so remarkable that he immediately committed it to writing:

* * * * *

There was great excitement in the central village on the lower Nass [River] in response to an invitation which had been sent out some weeks previously. The tribes were assembling from every camp on the river. Some great event was about to take place. The canoes which had been sent to summon the chiefs were manned by young braves, who cried aloud in front of the various camps, that the head chief had discovered the Gan sha-goibakim-Labah, or that which enlightened the heavens, and was about to lead an expedition to procure it.

It was further announced that the leading chief of every crest and clan who joined in the expedition should receive a share in this wonderful discovery.

An ambitious hunter of the tribe, who had ascended the highest mountain on his hunting ground in quest of the mountain goat, was overtaken by the sunset when near the summit. There he was compelled to seek shelter in a cleft of the mountain for the night.

He was not without food, as he had shot a young sheep early in the day. This he had skinned, and then having rolled up the choicest portions of the meat in the skin, which he had first scraped and cleaned carefully, he had cached it in a crevice of a rock where the wolves and wolverines could not find it.

To this natural food depot he now descended, and having abstracted a choice cut he kindled the fire, and impaling his steak on a stick, inserted it firmly in the ground leaning towards the fire. It was soon frizzling and roasting.

While waiting in pleasant anticipation for his evening meal, he drew his pipe from his belt, and having filled it, he applied a burning cinder and puffed away, with his gaze fixed on the fire.

Rev. W.H. Collison and family. —Wikipedia

Suddenly he was startled by the cry of a wolf nearby on the mountain, which was quickly answered by a whole pack lower down. At once he realized what had occurred. This solitary wolf which he had first heard had discovered the portion of the sheep which he had discarded, and was summoning the pack to the feast.

Concluding that prudence was the better part of valour, he instantly seized his gun, and grasping the stick on which his evening meal was roasting, he rushed up the mountain. Higher and yet higher he hastened, with the howling of the hungry wolves ringing in his ears. He was no coward, as he had often faced both the grizzly bear and the wolf in fierce conflict, and brought them down with his trusty weapon. But now the night was overtaking him; he knew he could but fire at random in the darkness and waste his precious ammunition.

Meanwhile, the wolves had ceased their howling, and he knew they were engaged in devouring the remains of the sheep, as an occasional angry yelp indicated the struggle which was taking place over it.

Still he continued his upward flight, and now reached the point where hunter’s foot had never trod before. Nor could he climb higher, for a glacier hung like a curtain from the crags above him.

Brought thus to a stand, he looked around and discovered an opening, into which he passed. To his surprise and satisfaction he found it was a lofty opening, with the roof sloping upward and outward. And as he gazed he was attracted and astonished by what he supposed to be a number of icicles, suspended from the overhanging roof of his shelter. But on closer examination he found they were not icicles but stalactites, of which several had fallen to the rocky floor underneath and been broken.

A miner could not have been more delighted on discovering a gold mine than was the hunter on the discovery of this gallery of crystals. For he had often heard thrilling tales of the discoveries of such treasures in the past, and how some chiefs had become great and wealthy by purchasing numbers of slaves with them.

Some calcite formations resemble icing on a giant wedding cake, —Author’s Collection

He was not much troubled with the fear of the wolves, so elated was he with his great discovery. Besides, he knew that they had descended the mountain again. They had followed his trail to the fire which he had left burning right in the centre of the narrow pass; fearing to pass it they united in a final concert of howling, then retreated down the mountain.

He then unbound his rabbit robe, which he carried slung over his shoulders, and wrapping himself in it he placed his gun near to his side and lay down to rest till the day should dawn.

But sleep he could not. His mind was too full of his discovery, and as he lay looking upward he could see the starlight flashing from crystal to crystal and illuminating the roof of his shelter with the rays.

At length he slumbered and dreamed of wolves and crystals until he saw the pack of wolves rushing up in an attack on his treasures, from which he awoke with a start, to find that the day was breaking. He arose quickly and hastened down to his fire, and finding a few sparks still burning he quickly replenished it and fanned it into a flame. Hastening back to where he had hidden the meat he took a portion from the natural safe, and returning to the fire he roasted it, and feasted on it for breakfast. This he concluded by a draught of water from a stream which trickled down the mountain.

Thus refreshed he started on his return journey to the camp, where he related to the astonished tribesmen the story of his great discovery.

This, then, was the cause of the gathering described before. It was to acquaint the chiefs of the neighbouring villages of the news of the discovery, and to device plans for obtaining possession of the prizes. It was at length decided that a strong and very long basket should be constructed, together with some new bark ropes, and that a slave named Zidahak, who was famed for his ability in climbing to dizzy heights, should be lowered in this basket from the top of the mountain to the gallery where the glistening crystals hung.

While these preparations were being made Zidahak was the hero of the hour, and in the enjoyment of his honours he quite forgot he was a slave. The lucky finder was also rewarded with many presents, and promises of more when the crystals were brought home. For this purpose a number of the strongest of the braves from each tribe was selected to accompany Zidahak to the mountaintop, and to lower him down to the treasures.

Many were the charges he received as he took his place in the basket to be lowered down to the much-desired gems.

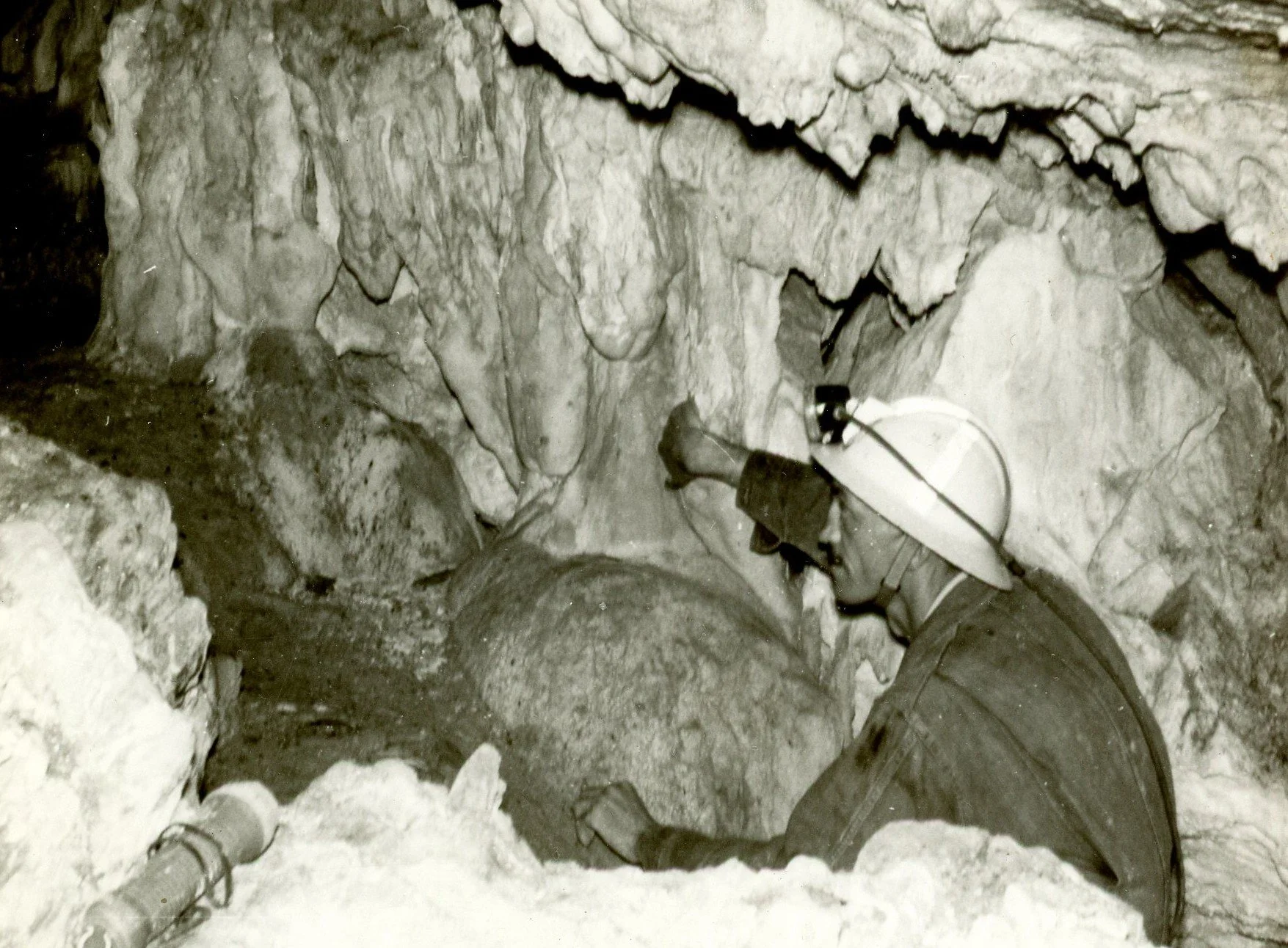

Zidahak was instructed to retrieve stalactites. But limestone also forms lava-like flows such as shown here. —Author’s Collection

A signal was agreed upon, which Zidahak should give when ready to be drawn up, and this dome he was gently pushed over the edge of the precipice. Hand over hand he was gradually lowered downwards and yet downwards until but little of the rope was left, and they began to fear that it would prove too short to reach the prize.

But just then within a few feet of the end, a jerk of the rope thrice repeated from below indicated that he had reached the spot. Securing the rope to a spur of rock they sat down to await results.

Meantime Zidahak was not idle. Now with this right hand and now his left, and occasionally with both hands, he was pulling off first the largest stalactites within his reach and then the smaller, and packing them in the basket around his feet and legs.

Higher and higher he packed them, without reflecting for a moment on the weight which he was adding every minute to his load. And now, as the basket was quite full, he placed several under his arms, and then gave the signal agreed upon for hauling him up. Slowly, inch by inch, the basket began to move upward, creaking under its weight.

Now he could hear the shouts of the young men above as they heaved away in concert on the strained rope. And still they toiled on, trusting to Zidahak to guide the basket and keep it clear of the projecting ledges of the rock steep. This he endeavoured to do, and was successful in his efforts until near the top. Just here was a sharp projection, and as the pull on the rope was more inward now, he was unable to keep the rope off the rocky ledge.

Suddenly a strand of the rope was severed by the sharp ledge of rock, and he cried aloud to warn them of the danger. But instead of trying to devise some means of repairing the damage, and fearful of losing the prize now it was almost within their reach, they all united in a strong pull together.

Instantly the rope parted and all the party were thrown on their backs. The basket with the unfortunate slave and all his hard-won treasures was hurled downward several hundred feet. His body, together with the stalactites, bounded and rebounded from rock to rock and from ledge to ridge, until arrested about midway down the mountain.

There they found him, a mangled mass, but on unfolding his inner garment, or what were you what remained of it, they found six of the smaller but more perfectly formed crystals lodged, three under each arm, where he had clasped them even in his death fall. Of the others only broken scraps could be found here and there scattered down the mountain.

After the young men who had formed the expedition had cremated the remains of the faithful slave Zidahak, they hastened to return to camp with the six stalactites thus preserved. There was much mourning and lamentation in the camp when the sad news was announced; but their sorrow was not for the unfortunate slave Zidahak, but rather for the treasures which had been lost with him.

The six crystal stalactites which had been preserved were exhibited for several days in the lodges of the leading chief, and hosts of Indians from all the tribes entered to examine and admire them. They generally ended their examinations with exclamations of sorrow for the Lost crystals. “Alas now, how sad that such a number of these costly crystals should have been lost. Iowa. Alas!”

But not a word of regret for poor Zidahak.

A meeting of the chiefs and their counsellors was then convened, when the crystals were named and distributed to the leading chiefs. The first crystal was named Aizuli, or The Eldest, and was presented to Chief Neishlishyan, or the Grandfather of the Mink. Of this crystal, a chant or song was composed by the music master of his tribe, which was sung on special occasions, as when a potlatch was made.

The second stalactite was named Tka-ga-Koidiz, or the Coming of the Whole. This was presented to Chief Gadonai, and a song was also made for it.

The third crystal stalactite was named How-how-imsh-im laub, or the Lion Stone, and was presented to Chief Klaitak, the predecessor of the chief who narrated the incident. A chant was also composed by the music master of the tribe for this crystal.

The fourth crystal was named Daow-im-Latak, the Ice of Heaven, and was presented to Chief Gwaksho, who was the chief bear hunter on the river, and killed a bear on one occasion without any weapon but his teeth.

The fifth crystal was named Kalga Lagim Lakan, the Great Fire Glass of Heaven, and was presented to Chief Neish lak-an-noish, who was a Tsimshian chief, but had married in Nishga chieftainess. This chief was famous for his skill as a carver and designer in gold, silver, and wood.

The sixth and last of the crystal stalactites was named Gwe-yel, and was presented to Chief Ginzadak, who after a hard life of raiding and fighting with other tribes at length became a Christian.

A great song was composed by the music masters of the camp in commemoration of the finding of the crystals, and the circumstances connected with it. This song was named Maouk, and was sung annually by the tribes when they assembled for the potlatch, or for Yiaak, on the lower river. They were generally known as Giatka-deen, or The People of all the Valley.

Such was the story as related to me by Chief Klaitak. The Lion Stone, which had been presented to his predecessor, was now in his possession, and as I was desirous to see this ancient treasure my request was granted. The young chief in whose charge it had been placed, favoured me with a view.

It was carefully hidden away in a strong chest in his house, and no one was admitted but myself on the occasion. It was evident from the care with which he exhibited it to me that he still considered it a crown jewel.

The stalactite was eight to 12 inches in diameter. It was hexagonal in shape, and looked like cut glass. As I examined it, I was pleased to remember that not only the old chief, who had told me the story, but also nearly all the chiefs to whom they had being originally presented, had [not] heard an older story of greater and more enduring treasure than this.

* * * * *

That’s the remarkable story of the Cave of Crystals as recorded by Rev. W.H. Collison. As a former spelunker I’ve been blessed with seeing such wonders as the stalactites described, in their natural, undisturbed settings. The artistic wonders wrought by water and limestone can defy the imagination and must be seen close up to truly appreciate.

I’d love to know what became of the six stalactites for which poor Zidahak gave his life.