The Cowichan Connection to Ross Bay Cemetery

I can clearly see them now, 20-odd years later: the two older ladies in the back row as they turned to each other, their faces puckered as if they’d just sucked a lemon.

As entertainment convener for the Cowichan Historical Society, I’d just announced that the next month’s speaker would be John Adams of the Old Cemeteries Society, Victoria (https://oldcem.bc.ca).

It was the idea of talking about cemeteries that distressed these ladies.

Ooh, morbid!

Well, I beg to disagree.

I’ve spent 100s of hours, driven 1000s of miles, visiting cemeteries throughout southern B.C. and on the Island. To coin a phrase, I’ve never met a cemetery I didn’t like.

—https://www.findagrave.com/cemetery/639348/Ross-Bay-Cemetery#view-photo=46287385

Some, of course, have been standouts. My favourite, for a variety of reasons, is our own St. Peter’s, Quamichan.

But, much as I’m drawn by the peaceful settings, usually of trees and other greenery amidst a surround of pavement and traffic, it’s the stories that appeal to me. I mean, really, if the headstones and family monuments were meant to be private, why do they write on them?

Hence the title of my 2012 book, Tales the Tombstones Tell: A Walking Guide to Cemeteries in the Cowichan Valley.

But it’s a select few of the wonderful stories of Ross Bay Cemetery that I’m going to tell you about in this week’s Chronicle.

Obviously, I’m not even going to begin to try to cover all the occupants of the 28,814 markers spread over 11 hectares (27.5 acres) overlooking Ross Bay since 1872. Nor am I going to deal with the cemetery’s more illustrious residents that include a Father of Confederation—there’s a treasury of information available elsewhere, including online, for those so inclined.

For the series of tours I did over the years for the Old Cemeteries Society (“dedicated to researching, preserving and encouraging the appreciation of Victoria’s heritage cemeteries” since 1987) I usually described some of the lesser-known, even unlamented, pioneers, characters, eccentrics and outcasts from my research for yet another book, Capital Characters: A Celebration of Victorian Eccentrics.

But, today, several Ross Bay Cemetery residents who have deep Cowichan Valley roots. Here goes...

* * * * *

Let’s begin with Edward Lemon, a 22-year-old Cowichan Bay logger who met his fate on a Victoria gallows in 1884 for the shooting of a friend during a drinking party.

The case for the Crown, as presented before a jury and Chief Justice (“Hanging Judge”) M.B. Begbie, was straight-forward: Lemon had plied the victim and the latter’s wife with rum-laced tea that he might take advantage of her. But, drunk or not, Mary had resisted his advances and called upon her husband, Johnny, to help her.

Lemon, who supposedly had watered down his own drinks, had the advantage and stunned Johnny with a chair. When the dazed man stumbled outside, Lemon followed with a single-barrelled shotgun, shouted, “Look out, I’m going to shoot you,” and fired.

As Mary watched helplessly, Johnny died on the spot.

Lemon argued self-defence, saying that Johnny had attacked him with a knife and showed a cut in his coat as proof. Although it took a jury only half an hour to find him guilty of murder; they unanimously recommended mercy.

So-called ‘Hanging’ Judge M.B. Begbie. —www.biogaphi.ca

Begbie, belying history’s conception of him as a merciless judge (he wasn’t—Ed.), sentenced Lemon to die but delayed execution for five weeks, that the Dominion authorities might consider sentence.

But, after a further month-long reprieve, Ottawa ordered that execution be carried out.

“Poor fellow!” wrote a Victoria newspaper reporter after interviewing him in his cell. “One cannot [deny] a feeling of sadness that his young life is about to be cut short by a crime committed in a state of intoxication.”

At 6:00 a.m., May 31, 1884, Edward John Lemon who said he accepted his fate and embraced God, mounted the gallows erected in Bastion Square with a firm step. He glanced at a bright blue sky overhead then down at the “blanched” faces of his official audience. The hood was slipped over his head and the trap sprung.

Twenty minutes later, Dr. John S. Helmcken pronounced life to be extinct.

Authorities ordered Lemon’s remains to be interred in Ross Bay Cemetery, overruling the request of Johnny’s father that Lemon be returned to Cowichan Bay for burial. A day prior to execution, the blanket-shrouded father declared, “...I saw my child lying dead before my eyes...

“I could have killed Lemon, but I did not. I wanted to try the laws I have [heard] so much about... I want to see him hang tomorrow.

“Then I want to get his body and lay it by the side of my poor son beneath the trees in Cowichan Valley. There they both will be happy together and I shall be satisfied when I die to be laid between them. I do not hate Lemon; but I want him to be hanged because he took my son’s life.”

Denied access to the execution, Johnny’s father joined scores of Victorians in watching from nearby rooftops as Edward Lemon plunged into oblivion.

Hence his interment in Ross Bay Cemetery, Block: K Plot:2W7. It’s unmarked, of course.

* * * * *

Henry Croft, a Victorian but of Chemainus sawmill and Mount Sicker copper mining fame, is here in the RB Cemetery but I’ve told his story in newspaper columns, online posts and in my book, Riches to Ruin.

I’ve also introduced Chronicles readers to Edgar Fawcett, author of the priceless history, Some Reminiscences of Old Victoria.

I’ve written, too, about Theodore Davie, one of three provincial premiers (Theodore, his brother Alexander and William Smithe) with Cowichan roots.

Born in Brexton, South London in 1852, Theodore came to Cowichan at age 17 after his mother’s death, his father and brothers having preceded him. He became a lawyer, dabbled in mining in the Cassiar gold rush of the 1870s and gained notoriety for marrying 14-year-old Blanche Baker who died just two years later.

Theodore ran for the legislative assembly and upon William Smithe becoming premier and brother Alex attorney general, he served as an “ardent and able” back bencher.

Twice-premier Theodore Davie. —Wikipedia

Upon Smithe’s premature death brother Alex assumed the premiership and Theodore became the attorney general. When Alex also died in office, in 1896, it cleared the way for Theodore to become premier. Re-elected to a second term, he resigned to become Chief Justice of British Columbia. By then he was ill and, like his brother and Smithe, died young, just 46.

Theodore Davie’s greatest contribution while in office is said to be his commissioning of architect Francis Mawson Rattenbury to design Victoria’s Parliament Buildings.

The Cowichan Valley, it should be noted, is one of the few B.C. communities to give three premiers, all of them, it would seem, jinxed. As noted, two died in office, the third shortly after resigning the premiership. All died young.

* * * * *

Richard Golledge wasn’t exactly a resident of the Cowichan Valley, even briefly, but he’s a close neighbour if you look at a map, having left his name on a Malahat creek.

Appointed acting gold commissioner for the Sooke mining district during the Leech River gold rush excitement in July 1864, he’d previously served as Colonial Governor James Douglas’s private secretary and later as a justice of the peace.

But the man who died in July 1884, 20 years later, was but a shadow of the young Golledge, having fallen from a position in the highest office in the land to that of convicted thief.

Today, little is known of the man who for seven years served as Douglas’s private secretary. It seems apparent that, embarrassed by his antics of later years, his former peers and acquaintances disowned him. Only the briefest mention, and then only in reference to his official capacity, is made of him in official records or in personal memoirs.

The single exception is a blow-by-blow account of what amounts to his being drummed out of government service.

It’s known that he came to outpost Vancouver Island in 1851 when about 20 years old as an employee of the Hudson’s Bay Co. On one point few disagree: Richard Golledge came from a respectable family and had enjoyed a full education.

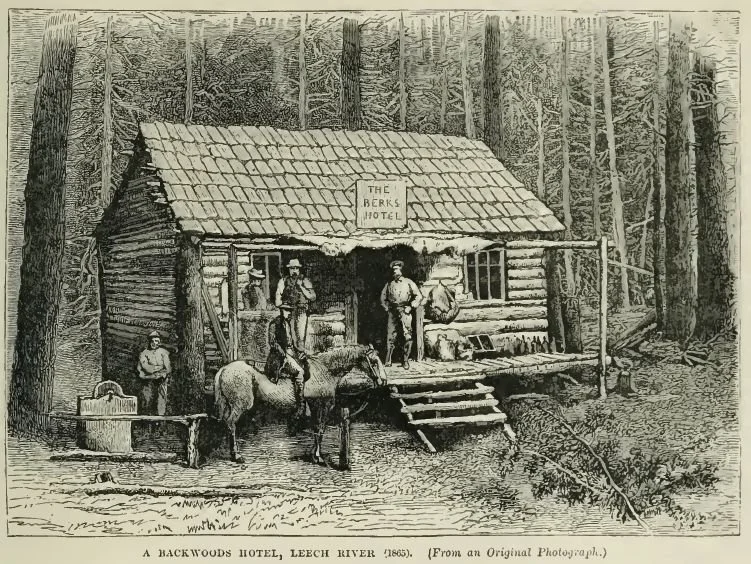

Upon his arrival in Victoria until 1858, he worked as the governor’s secretary, attending to the 101 minor details which daily beset the austere father of our province. In 1858 he left Douglas’s service and isn’t mentioned in print until the July 1864 announcement of his appointment by Vancouver Island Governor A,.E,. Kennedy as acting gold commissioner at booming Leechtown.

It doesn’t look much and probably wasn’t, the Berks Hotel in short-lived gold camp, Leechtown, where Richard Golledge set up shop as the colonial gold commissioner. —www.leechtownhistory.ca

On August 4 Golledge, apparently fulfilling his duties with enthusiasm, sent his second dispatch to Gov. Kennedy, outlining the events taking place on Leech River where the discovery of placer gold had drawn 100s of fortune seekers to what was hoped to be a new El Dorado.

Golledge seems to have caught the spirit of things, breathlessly reporting, “I have the honour to report that affairs are progressing in a very satisfactory manner, both in regard to the finding of good paying prospects, the numbers of miners gradually coming upstream, and the working of the present mining regulations.”

Cobble Hill pioneer (and fellow eccentric) Alfred Rogers, one of the many who didn’t find their fortunes on Leech River, described Golledge in his memoirs as “quite young, violently red-haired...inexperienced”.

The miners treated the young commissioner with contempt, dismissing his haughty claims of office by laughing at him or turning their backs on him, at which, Gold Commissioner or no, Gollege would slink away, license fees uncollected.

As it happened, the fortunes of Leech River were as fleeting as those of poor Richard. When next we hear of him, he’s been arrested for stealing a canoe, and Mr. Justice Fisher of Esquimalt has fined him $10. By this time, the Colonist has had enough of him: “...It is hoped that Golledge will rid the province of his presence, which has become very distasteful to respectable people.

“He took to drink and prowling about Indian [sic[ villages nearly 20 years ago, and has become a confirmed vagrant.”

But Richard didn’t rid the province of his presence until three years after when the same newspaper reported that he’d died of heart disease in St. Joseph’s Hospital. He was 55. The obituary mentioned only his former positions as governmental secretary and as a gold commissioner, noting that he’d once enjoyed wealth and prominence, that his “connections are prominent people”.

For a year prior to his death the Sisters of St. Ann had cared for him—out of pity, it was said.

It’s fortunate for him that Golledge Creek was christened before his downfall. But it’s never too late to do the ‘right thing’—historical revisionist, take note!

* * * * *

We know no more about Archibald Howie than we’re told in this snippet from the Cowichan Leader of Aug. 15, 1908: that the “resident of this district for a num[ber] of years passed away after a long lingering illness at St. Joseph’s Hospital last Sunday, and was laid at rest in the Ross Bay Cemetery on Wednesday last.

“Mr. Howie was a native of Hadingtonshire Scotland and was well fitted to be a pioneer in a country such as this, as he was strong, temperate and industrious. He joined the Klondyke gold rush in ‘97 and after working for some time near Dawson he went to Nome, walking the whole distance of [650 miles as the crow flies] on the ice. He was one of the few who were successful in the Northern Country.”

* * * * *

Young Royal Canadian seaman Austin Ordano has two stone memorials, one in Ross Bay Cemetery the other, a family marker, in St. Peter’s, Quamichan Cemetery, but no known grave having been lost at sea in the sinking of HMCS Galiano.

The fisheries patrol vessel was pressed into service with the RCN in 1917 and foundered between the northwestern end of Vancouver Island and southernmost Haida Gwaii, Oct. 30, 1918. There were no survivors and only three bodies were recovered.

The RB Cemetery memorial lists the names of 39 officers and men who were lost at sea; of these, 36 are from HMCS Galiano. Unfortunately, Austin Ordano’s name is misspelled; it’s correct in St. Peter’s Cemetery. The Canadian Force’s Fleet School Esquimalt named its damage control training facility after the ill-fated Galiano.

HMCS Galiano. —Wikipedia (Canadian Dept. of National Defence)

Is young seaman Austin Ordano in this photo? —www.forposterityssake.ca

There are other ‘Cowichan Connections’ in Ross Bay Cemetery, among them the colourful J.H.S. ‘Sam’ Matson of Mount Sicker and Cobble Hill fame, but this is enough for today. You can learn more about Sam and his connection to Henry and Mrs. Croft and Mrs. Robert Dunsmuir in Riches to Ruin.

* * * * *

Many years ago when I realized that I needed to upgrade my photographic skills to complement my writing, I talked two friends who shared my interest in cameras to accompany me once a week on practice shooting assignments. Usually, we did this on a Sunday, from mid-morning to dinner time, depending upon the season and weather.

When I became interested in twilight shots we haunted the waterfront and practised, practised...

One winter evening while so engaged we found ourselves driving by Ross Bay Cemetery and the thought struck us as one that wonderful photographic opportunities lay therein in the way of headstones back-lit by a moon-and-cloud sky.

You could drive right in, in those days, and we did.

We took a few shots and, as we climbed back into Paul’s car, we were suddenly ablaze in the flashing lights of a police car. A neighbour, afraid that the cemetery was being vandalized, had turned us in.

Now, the one thing I haven’t mentioned so far is that, on this particular evening, two of us (not your reporter, it hardly needs be said) had generously armed themselves against the winter chill with cheap wine and vodka.

Now this is never a wise mix but Paul, to all outward appearances, was stone-cold sober. I was in the passenger seat and Dave in the back, not on the seat exactly, but half-slumped on the floor and not to be seen.

By this time one of the constables, who proved to be in his early 20s as we were, was alongside with his flashlight which he flicked across the front seat as he looked critically at Paul and me and asked for Paul’s driver’s license and what we were doing in the cemetery at that time of night.

From the front passenger seat my eyes were more or less level with the constable’s waist once he’d straightened up to examine Paul’s papers. It was as he leaned forward again to return them with a polite but firm suggestion that we confine our cemetery tours to the daytime that Dave roused himself from the floorboard, sat up, and made his presence known to the officer for the first time with a loud, “Hunnhh?”

Perhaps it was the fact we were in the almost total darkness of a windy, wintry night in Ross Bay Cemetery that did it. Perhaps it was Dave’s sudden rise from the dead of alcoholic excess that startled the young constable.

Whatever it was, when Dave’s head popped up from the back seat with his guttural query, that cop—I swear—went straight up in the air. Instead of looking at his belt buckle I was, if only for a moment, looking his knees.

Now that’s being scared!

* * * * *

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.