The Curse of the Jamieson Brothers (Part 1)

I’ve long joked that I’ve sunk more ships than Lord Nelson—in print.

And I owe that dubious claim, in part, to a lady who, long ago, did me a small favour. Or so it seemed at the time.

In fact, she firmly set me on my course as a writer/historian and I’m deeply indebted to her to this day.

Miss Fawcett—that’s all I knew her by, no Christian name or initials—lived next door to my high school chum Bruce, in Saanich. As we did all “old maids” or spinsters, we teenagers thought she was crabby and viewed her with disdain and just a teensy measure of respect—or fear, really, as she sure could express herself and make her presence known to us.

But, no big deal: she quietly lived her life next door to and as a friend of Bruce’s mom. One day, I’m assuming, Mrs. Broadfoot, knowing that Miss Fawcett was the daughter of Edgar Fawcett, author of the highly collectible Some Reminiscences of Old Victoria, mentioned to her my interest in writing and history.

Next I knew, she’d offered to let me read—not borrow—her father’s book. So it was arranged that I could read a few chapters at a time at Bruce’s house.

And the rest, as they say, is history.

One of the first things I read mentioned the pioneer steamship Cariboo in Victoria Harbour. I was enthralled. All the drama and excitement of a boiler explosion and death, not in the faraway B.C. Interior or even more distant U.S., but almost in my own backyard, Victoria!

The jinx of the riverboating brothers was already at work by the time Capt. Smith Baird Jamieson met disaster on the Fraser River.

Such was my introduction to the ill-fated Jamieson brothers, all of whom became steamboat captains and engineers, all of whom died young and tragically.

What a story!

I’m forever indebted to Miss Fawcett for seeing past the brashness of my teen-hood and trusting me (albeit with Mrs. Broadfoot for a chaperone) with her only copy of her father’s book which I’ve since acquired at considerable cost.

* * * * *

“On a pleasant evening early in April 1861, the hotel de France on Government Street in this city was a scene of unwonted interest, brilliancy and activity...”

So began a 120-year-old reminiscence of that sparkling occasion when, more than a century before, in 1861, the leading citizens of Victoria honoured the man whose foresight and determination had mastered steamboat navigation on the Fraser River: John Kurtz, founder of the Yale Steam Navigation Co.

For two years the Fraser had been the gateway to El Dorado, the newly-discovered placer gold deposits of Interior B.C. It had been at the urging of colonial governor James Douglas that the sternwheel steamer Umatilla ventured as far upriver as Yale during high water, in 1858.

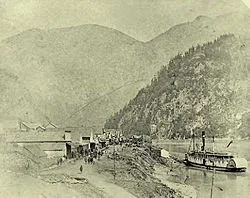

Fort Yale was a regular steamboat stop by 1882 when this photo was taken. —Wikipedia

But it had been John Kurtz who, with $40,000 capital (a king’s ransom in those days), proved that the Umatilla’s feat could be duplicated and made a practical, profitable business of providing regular steamship service between Yale, Victoria and the outside world.

In fact, his S.S. Fort Yale was an instant success, “skim[ming] the troubled [Fraser River] waters like a huge bird. Skilfully handled, she avoided rocks, bars and riffles and landed her cargo at Yale on the second day. Returning, she left Yale in the morning and in the same evening landed passengers and freight at Victoria.”

So popular was the new steamer, in fact, that shares in the Yale Steam Navigation Co. Sold at a premium and all promised well for the new company and their new boat.

Thus, with John Kurtz’s announced departure for California, the banquet in his honour in the Hotel de France.

That spring evening, as festivities began, the Yale puffed quietly at her Inner Harbour wharf while freight and passengers were hustled aboard. Upon Capt. Smith Jamieson’s return from dinner, she’d again sail for Yale.

While the party-goers enjoyed themselves, the S.S. Fort Yale loaded passengers and freight at her Inner Harbour wharf.

But, what should have been an auspicious occasion was to be marred by tragedy.

It had been a beautiful spring day, one guest recalled years after, and the banquet began happily, the hotel’s management having made every effort to make the banquet a success: “The table was laid in the restaurant of the hotel and every viand and liquid that would stimulate and coax the appetite were there in abundance.”

Master of Ceremonies was Wharf Street merchant E. Grancini, the guests including most of Victoria’s most prosperous businessmen, including mayor Tom Harris, Solicitor-General George Pearkes, the Hon. Dr. J.S. Helmcken (then speaker of the first Legislative Assembly), newspaper publisher Amor de Cosmos, senior officials of the Hudson’s Bay Co., and others.

The banquet proceeded spectacularly. By midnight, guests were still going strong, “the fun wax[ing] fast and furious”.

But for a few older guests who couldn’t keep the pace, none was anxious to excuse himself as the program included the merry company’s escorting Kurtz to Esquimalt, where his ship sailed at 6:00 next morning, by hired teams.

Early that morning as the revelry continued, Kurtz was approached by a waiter who handed him a card. Excusing himself, the guest of honour returned a few minutes later to announce that an acquaintance had arrived from Yale and asked that he might join the party. When Kurtz introduced him as a “nephew of Lord Portman,” a loud chorus invited the visitor to join them, at which the newcomer, named Esdale, entered the banquet room.

About 25 years of age, he was described as being of medium size, dark, almost swarthy. “He was neatly dressed and had the appearance and bearing of an English gentleman. As he advanced into the room he made a low obeisance to the chairman and was conducted to a vacant chair at the side of the guest of the evening—said chair having been vacated by one of the company who had found the conviviality too vigorous for his comfort.”

Within minutes, ‘Lord Portman’s nephew’ was one of the company, his “beaming, sunny face lighted up by a pair of bright, black eyes and a radiating smile that seemed to be catching,” winning him instant acceptance.

The festivities continued at an ever-increasing tempo, entertainment of varying degrees being provided by those who insisted upon giving testimonials to John Kurtz’s unlimited greatness and charm, and by raconteurs----even an Italian ditty by Chairman Grancini.

Among those to stand and entertain was young Esdale who offered as his contribution “a most eloquent and witty” speech that endeared him to his fellow guests. Upon retaking his seat, he was acknowledged with cheers and several bars of “For he’s a jolly good fellow,” his contagious charm (not to mention almost every kind of liquid cheer) having overshadowed, it seems, even that of the guest of honour.

So popular had Esdale become, in fact, that, with the single exception of John Kurtz, he became the most sought-after man at the head table. All wished to share a glass of wine with him, our informant noting that he’d evidently dined generously “before he came to us, but his holding capacity seemed unlimited. He drank with everyone who offered, and was none the worse for it, so far as we could see.”

By 2 o’clock, the revelry was at its peak.

Then, as was customary, each and every man present was called upon to to make a contribution to the evening with an anecdote, song or dance. Esdale outshone all by doing each “graciously and well,” his nearest competitor retiring from the field with the good-natured announcement that, henceforth, he’d tell no more jokes or stories.

With dawn, the hired hacks appeared as scheduled and their drivers were graciously invited to partake of a warming drink. Within half an hour, some had so warmed their chilled bones that they were in danger of becoming inebriated. This, however, didn’t bother the guests who, for the most part, were in no condition to appreciate the situation.

Actually, all were in such a state that the office of master of ceremonies had fallen upon Esdale, merchant Crancini having run out of steam. More time passed with no sign of the party proceeding to Esquimalt, when a seemingly innocuous incident foretold of impending tragedy.

Esdale was in the act of passing a drink to one of the drivers when he tripped slightly and fell against the table. Recovering himself, he smiled in embarrassment and sat down. It had taken no more than an instant and, under the circumstances, appeared to be a reasonable result of his celebrating.

But, to one man at the table who was watching with growing alarm, Esdale’s slip had ominous overtones.

For, as his fellows continued their merrymaking, unsuspecting, Esdale’s facial contortions showed that something was terrible wrong. “An ashen hue [stole] slowly over his face. His eyes rolled and then became fixed and stared at one of the coal-oil lamps, The next instant he fell heavily forward.”

Almost instantly, all were aware that the banquet was over, that Esdale was gravely ill. As it happened, Drs. Helmcken and Trimble had left the party. However, someone soon returned with a young medical graduate named Ramsey who was staying in the hotel—in room 13, as it turned out.

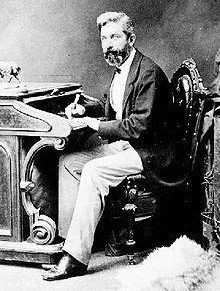

Unfortunately, Dr. J.S. Helmcken had gone home by the time Esdale went into medical distress. —Wikipedia

The inexperienced Ramsey “pronounced the trouble as delirium tremens and prescribed a composing draught—the very thing he should not have done, for Esdale was suffering from a stroke of apoplexy”. Soon the inevitable occurred and, in the florid prose of the day, “Death entered as the Uninvited Guest and bore away the bright, witty, handsome and cultivated Esdale, Lord Portman’s nephew.”

The tragedy rudely ended the celebrations and had the single beneficial effect of sobering many of the guests who sorrowfully made their way homeward, the intended excursion to Esquimalt forgotten.

Kurtz then proceeded to meet his ship with just a few close friends for company.

But Esdale’s death wasn’t the only grim outcome of that long-ago banquet which had begun with such high expectations and conviviality.

Long before festivities had reached their peak, Capt. Smith Jamieson had excused himself, boarded his ship in the Inner Harbour, and cleared for Yale. At Fort Hope he was joined by an old friend and competitor, Capt. William Irving. Proceeding upriver, the handsome steamer entered the first rapids above Hope as the dinner bell sounded.

With Jamieson in the wheelhouse was Capt. Irving who generously offered to take the wheel so the master could dine. With a grin, Jamieson declined, saying, “No, you don’t! No opposition steamboat captain can steer this boat for me!”

Within moments of Irving’s departure, the Yale’s boiler burst and the steamer became a drifting, splintered wreck. Among the dead was 26-year-old Smith Jamieson who died at his post. Capt. Irving, who’;d reached his table in the saloon, survived.

Passenger H.Lee Alley described the disaster: “The noise resembled, together with the crash, a heavy blow upon a sharp-sounding Chinese gong. The cabin floor was raised and then fell in; at the same time the hurricane roof fell upon us, cutting our heads more or less, and blocking up all means of escape forward of the dinner table.

“We quickly made for the windows and doors in the after-part of the cabin, and got on the roof of the hurricane house, and there beheld a scene that baffles all description, and such as I trust I may never witness again.

“The boat, but a few seconds before, nobly bucking against the swift current, was now a mass of sinking ruins from stem to stern—scarcely anything remaining in sight above water, but a small portion of her bow and the after part of her saloon, and those gradually disappearing below water.

“Firewood, trunks, barrels, boxes and thousands of splinters from the wreck were floating on the water. Five or six human beings, their faces streaming with blood, and presenting an awful appearance, were struggling for life. Several jumped overboard, but upon seeing the roof still afloat, desired to be hauled on board gain, and were got on by those of us on the roof—the port side of which was five inches out of water away aft, and the starboard side about level with the water.

“All the time we were floating downstream rapidly towards Hope.”

Of Capt. Jamieson, known for his “gentlemanly and honourable deportment,” there was not a trace, a witness on shore having reported that he saw him “go up into the air among the splinters” at the moment of explosion.

Ironically, the ship’s wheel was recovered, undamaged.

The final act in the chain of tragedy surrounding John Kurtz’s banquet was the foundering of his Yale Steam Navigation Co. Upon his death, aged 59, his was one of the largest funerals ever held until that time in Victoria. It was believed that one of his most prized possessions was his gold watch which had been given to him by fellow-directors of his ill-fated Yale Steamboat Co. shortly before the loss of their one and only ship.

All told, his farewell dinner had been a truly memorable affair—one of those tantalizing chapters of our history that continue to intrigue well over a century after. As does the story of the hard-luck Jamieson brothers who followed each other, almost like clockwork, in one disastrous shipwreck after another.

For years, Victoria’s last link with these brothers was a headstone in Quadra Street Cemetery (today’s Pioneer Square) where a headstone, long removed, bore the inscription, “In memory of Baird Jamieson, who lost his life in the explosion of the steamer Yale on the Fraser River, 14th April, 1861. Also Archibald Jamieson, and James Baird Jamieson, who lost their lives by the explosion of the steamer Cariboo in Victoria Harbour, 2nd August, 1861. Three brothers, sons of the late Robert Jamieson, Brodick, Isle of Arran, Scotland.”

Victoria’s Pioneer Square, the old Quadra Street Burying Ground, where a headstone once honoured three of the Jamieson brothers.

(Next week: Conclusion)