The Curse of the Jamieson Brothers (Conclusion)

From the craggy shores of Isle Arran they came, five brothers seeking their fortunes in the New World.

But the seagoing Jamiesons weren’t to enjoy the fruits of their labours. Instead, they met violent death in a series of explosions and riverboat disasters that made Pacific Northwest maritime history.

Isle of Arran’s Lochranza village and castle. —https://commons.wikimedia.org

Last week, I told how in my teens Miss Fawcett, a school chum’s next door neighbour, set me on the road to becoming a writer of British Columbia history by letting me read, under supervision, Some Reminiscences of Early Victoria.

This classic work by her father, Edgar Fawcett, set me afire with its mention of the explosion of a sternwheel steamboat in Victoria’s Inner Harbour in the 1860s.

I could hardly believe it!

Not in the American Wild West that I’d been reading about since I was a child, not even on distant mainland British Columbia, but in ‘downtown’ Victoria, my, so to speak, backyard. (I lived in Saanich.)

Hence my introduction to the hard-luck Jamieson brothers; hence last week’s Chronicle which told the story of the ill-fated John Kurtz farewell banquet that preceded the sailing, from Victoria’s Inner Harbour, of brother Smith Baird Jamieson’s handsome new sternwheeler, S.S. Fort Yale.

And, next day, the devastating boiler explosion that blew him to eternity.

There were six brothers in the Jamieson family of Brodick. One became a clergyman and remained in Scotland, but Arthur, Andrew, Smith and Archibald chose to try their luck in the booming riverboat fleets of the Pacific Northwest. James, the ‘baby’ of the family, was left to complete his apprenticeship as a machinist in a Firth of Clyde shipyard.

Smith and Arthibald chose the white rapids of the Fraser River while Archibald and Andrew joined the riverboat trade of Oregon. The sturdy Scotsmen soon made names for themselves throughout the Northwest for their reliability and skill as ‘swiftwater’ pilots.

In 1854, tragedy struck for the first time. Andrew, just 17, died from complications that followed his having been injured during the launching of the S.S. Gazelle which, like the Jamiesons, also was jinxed. On its second voyage its boiler exploded, killing half of those on board.

Three years later, Arthur’s steamer, the Portland, was carried over Willamette Falls; he and a deckhand were drowned when they jumped overboard. As fate would have it, they might have lived had they remained on board as the pilothouse survived more or less intact.

Then there were three.

Steamboat and barge traffic on the Willamette River. —Wikipedia

When John Kurtz, whom we met last week, and several other Yale businessmen formed the Yale Steam Navigation Co., they raised sufficient funds to build a steamer “second to no boat of the northern waters”. Costing $23,000 then a considerable sum for a riverboat, the Fort Yale was touted as being the finest craft then braving the Fraser’s treacherous currents. During the first five months of service under the popular Capt. Smith Baird Jamieson’s command, the new steamboat maintained a busy schedule between Yale, New Westminster and Victoria.

As told last week, on her fatal voyage she’d cleared the Royal City and headed upriver on schedule. It was just above Hope at the murderous narrows known as Union Bar Riffle, that disaster struck the Jamiesons a third time, on April 14, 1861.

Twenty-six-year-old Smith Jamieson was at the helm 10 minutes before the accident, talking with passengers H. Lee Alley, Capt. William Irving of the rival steamer Colonel Moody and George Landvoigt. When the dinner bell rang, Irving had offered to stand Jamieson’s watch while he ate with the others.

To which Jamieson had laughed, “No you don’t! No opposition steamboat captain can steer this boat for me!” And with that a grinning Irving had followed his fellow passengers to the saloon. Actually, Mr. Alley had lingered some minutes as he wasn’t hungry, then decided to join the others, leaving Jamieson in the pilothouse with crewman James Allison.

The passengers had just begun dinner when the Fort Yale’s boiler blew and the ship disintegrated in an horrendous blast with what Alley later described as having “resembled, together with the crash, a heavy blow upon a sharp-sounding Chinese gong. The floor raised and then fell in; at the same time the hurricane roof fell upon us, cutting our heads more or less, and blocking up all means of escape forward of the dinner table...”

But most of the passengers and crew were lucky—they survived. Among the dead, and in his case, missing, was Capt. Smith Jamieson whose body was seen by an onshore witness as it flew high in the air.

Twenty minutes after the blast, as frightened, stunned and bleeding survivors clung to the swirling hurricane roof, several Native canoes appeared, paddling desperately against the current to overtake the wreck. Finally pulling alongside, they were able to remove several of the most injured, including Capt. Irving and a Capt. Grant of the Royal Engineers. Mr. Alley and several volunteers remained wit the hulk, intending to halt its frenzied flight somewhere downriver.

As the smoking ruin drifted through the rapids, the survivors attempted to throw a line ashore in hopes of stopping it “if possible from going below Hope. But it was all in vain, for as soon as we got fast the line and the stern of the boat came to bear on it, [it] snapped like twine, although a large-size hawser of 2 1/2 inches in diameter.

“We tried twice or three times, and gave it up, and away we went down to the first bar below Hope, and there she lodged a total wreck.”

Besides Capt. Jamieson, Hope blacksmith Samuel Powers, fireman Joel Osborne (aka James Growler), cook Joshua Buchanan and an unidentified deckhand had been killed instantly in the blast. James Allison, also in the pilothouse with Jamieson, had been blown skyward but, miraculously, fell back into the wreckage, suffering little more than a bruising.

Engineer McGreavy, at his post in the engine room, was saved by the boat’s freight having been between him and the boiler. Thomas King, a deckhand, wasn’t as fortunate; a leg had to be amputated below the knee. Several other crew members and passengers suffered slight injuries.

Of poor Smith Jamieson there wasn’t a trace, a man watching the passing ship from the riverbank having seen him “go up into the air among the splinters”. The wreckage and both banks of the river were searched for some miles without success and it was feared that Jamieson had been “blown to atoms”.

The Victoria Colonist mourned the popular mariner: “Although only a short time on the river, yet by his quiet, gentlemanly and honourable deportment, he has secured the good will of all and the warm esteem and friendship of many... As a navigator, he was skilful, fearless and successful; as a captain, a universal favourite; and as a gentleman, unspotted.”

“Poor Jamieson!” said friend Alley. “He was a quiet, unassuming man, of noble and generous impulses, and none who understood his nature as I did could but like him and mourn his untimely end.”

Capt. Smith Jamieson was to have been married that week.

Pieces of the Fort Yale’s ruptured boiler were found half a mile from the scene of the disaster, blacksmith Powers’s body had drifted ashore, far from the wreck. The force of the explosion had stripped him of every piece of clothing.

Says later, search parties still hunted for Jamieson’s body, deckhand King lay near death. Inspector of Steamers Westgarth opened an inquiry into the tragedy, salvors stripped the wreck of cargo and machinery and Osborne and Powers were buried at Hope. The Yale’s helm, slightly damaged, was recovered below Harrison River.

In Victoria, patrons of the Brown Jug Saloon viewed a twisted piece of the ill-starred steamer over their beer. Those who claimed to know about such things solemnly pronounced the grim memento to be “composed of very inferior metal”.

A reader wrote the Colonist: “Poor Jamieson was beloved by all ‘poor travellers,’ and long will his loss be felt by those who can appreciate the commendation—too rarely found—of careful skill and gentlemanly bearing.”

The final tragic act in the lives of 35-year-old Archibald and ‘baby’ James had actually begun months before, in the early summer of 1860 when the keel of a sidewheel steamer was laid in Victoria Harbour. Designed to run between Victorian, Harrison River and Hope, the building S.S. Cariboo was Capt. Archibald’s pride and joy.

“The greatest care was bestowed upon her construction and one of the most experienced shipbuilders on the Pacific Coast came from San Francisco to superintend the work. As the vessel was fashioned into shape day by day her elegant lines won general admiration. She was meant to have speed and with this object in view engines and boilers of special design and great capacity and strength were ordered from Glasgow before the keel was laid here.”

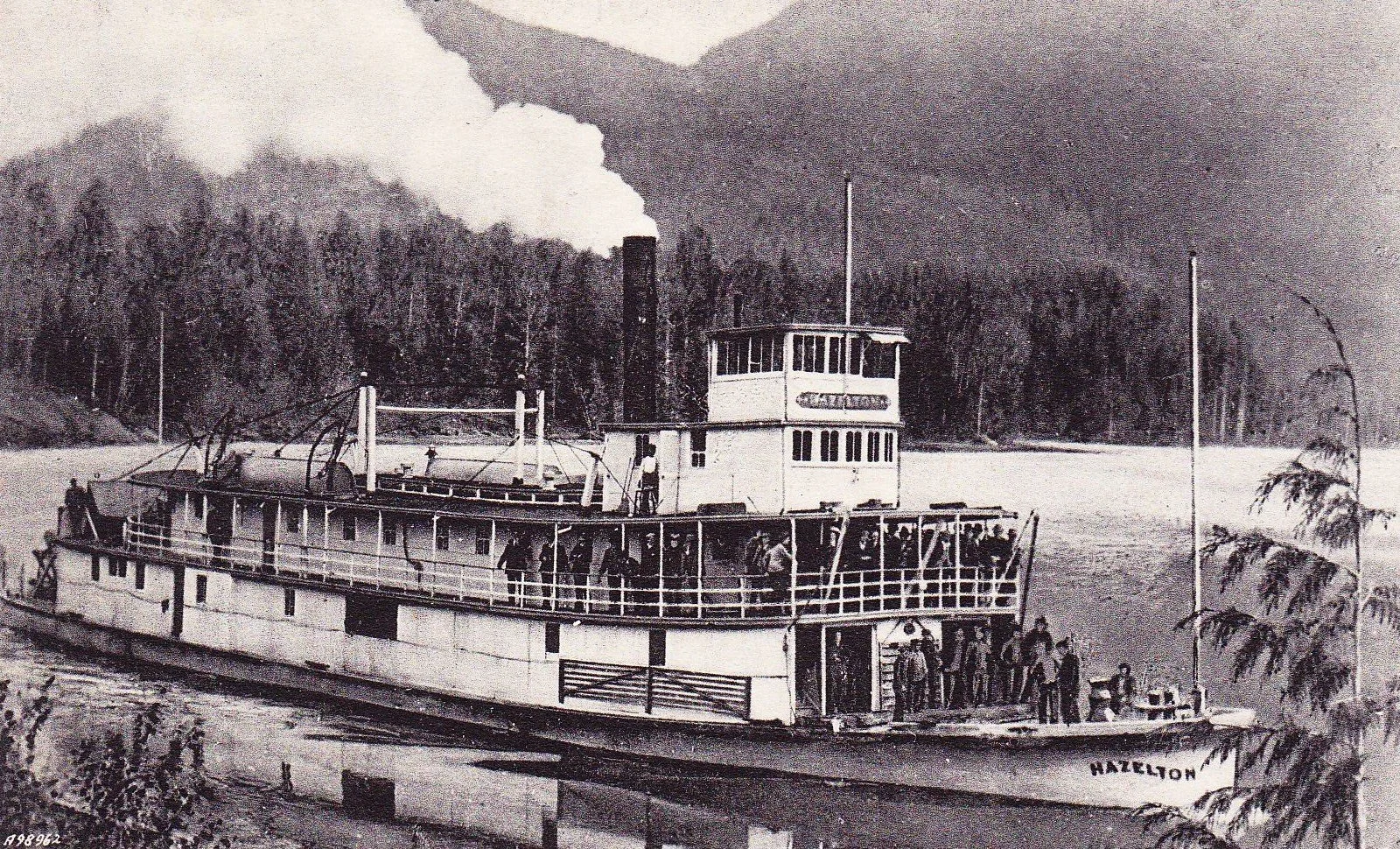

The Cariboo would have been a modest version of the later S.S. Hazelton which would also be lost, in the Stikine River. —www.Pinterest.com

It had been intended that the Cariboo be ready that fall but a series of mishaps delayed her completion by almost a year. Once, when finishing touches were being applied to her hull, timbers supporting her gave way, plunging her mammoth weight onto workers. One man died instantly, two were seriously injured, one man maimed for life.

The Jamieson jinx again at work?

When the hull had been raised and reset in its cradle, work continued. Finally came the day of launching. But, instead of sliding down the ways as expected, the recalcitrant lady stuck fast. And there she remained until harried workers jacked her, inch by protesting inch, into the harbour.

Then, as if all this hadn’t been enough, Capt. Jamieson encountered yet another delay; her engines hadn’t arrived from Scotland. In fact, they didn’t reach Victoria until the following spring. The same ship brought a second surprise for Jamieson, then in mourning for brother Smith Baird.

Young James—“tall, stalwart...of about 24 years”—had completed his machinist’s apprenticeship in the Old Country and was following in his older brothers’ footsteps.

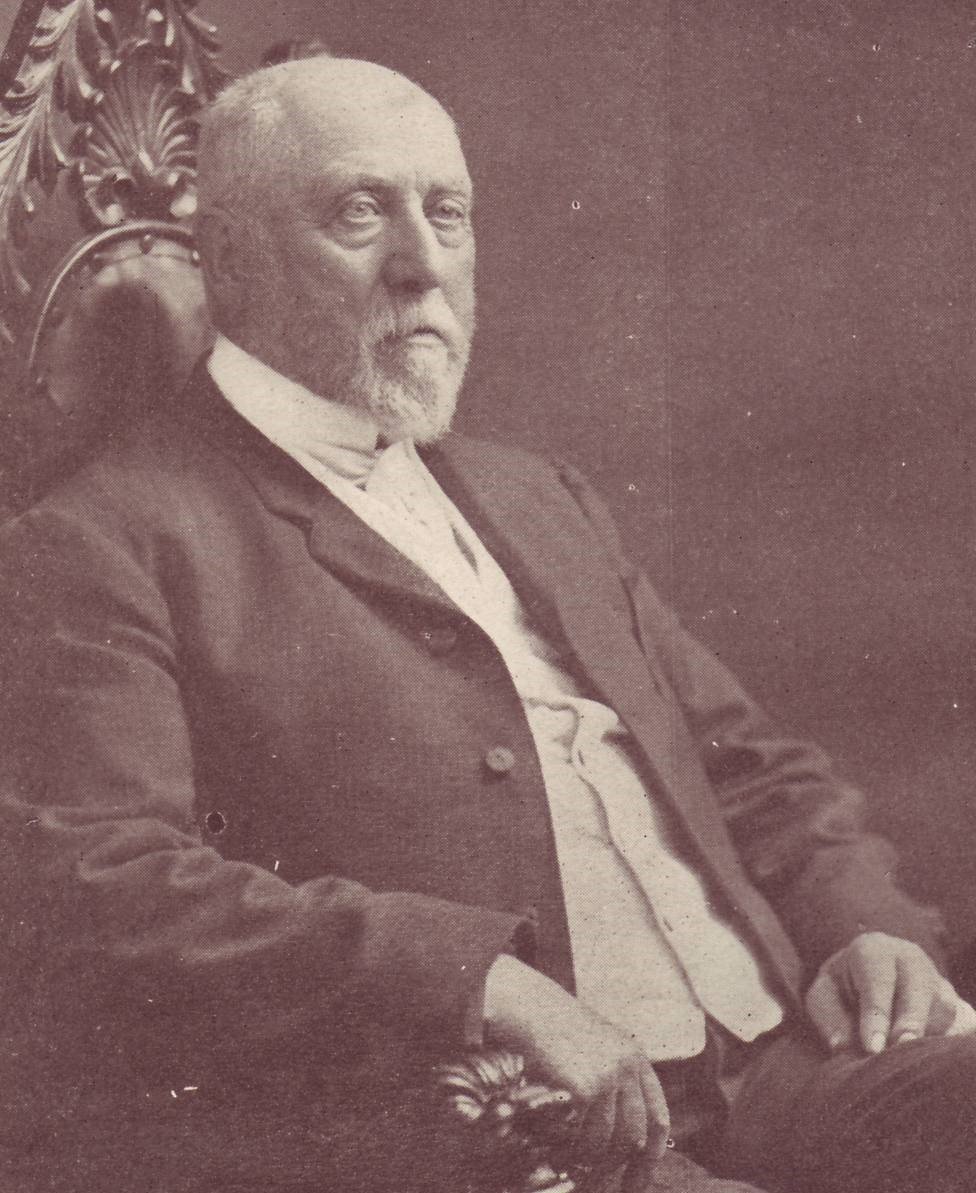

Pioneer journalist D. W. Higgins accompanied his friend Count Paul de Garro to the wharf where he was to board the S.S. Cariboo, about to sail for the Fraser River. Hours later, the Cariboo was a total loss with several of those aboard killed, including de Garro. —Author’s Collection

It was arranged that William Allen, unemployed since his ship Caledonia’s boiler exploded, would be hired as temporary engineer, James to assume charge of the engine room after a few voyages. In July 1861 the newly-commissioned Cariboo completed her maiden voyage to Harrison River during which she developed “great power and speed... The Cariboo’s performances gave satisfaction to {Archibald].”

Midnight, Aug. 2, 1861, Cariboo lay at the foot of Victoria’s Bastion Street. Among the crowd of well-wishers bidding farewell to friends setting out for the Cariboo gold fields was Chronicles contributor and pioneer journalist D.W. Higgins there to see friend Count Paul de Garrro off to the Interior.

They shook hands then de Garro and his black retriever boarded the steamer.

Sailing time came and passed without the arrival of Capt. Jamieson. Although steam was up, the Cariboo ready to sail on schedule, Archibald wasn’t to be seen. When he still failed to appear, Higgins decided he could wait no longer and walked several blocks to his quarters on the corner of Birdcage Walk and Belleville Street, on the south shore of the inner Harbour.

“I retired to bed, but for the life of me I could not sleep. A little clock on the mantel struck one and then half-past one o’clock and still I tossed from side to side. Sleep, although wooed with ardour, would not come to me. I was possessed with a strong feeling that an indefinable horrible something was about to occur.

“Every little while I could hear the Cariboo blowing off what seemed to be ‘dry’ steam in long-drawn volumes and disrupting the night air with the shrill notes of her whistle for miles around which must have disturbed others beside myself.

“At last I heard the cher-cher-cher of the paddles and then I knew that the Cariboo was off.”

Finally, thought a relieved Higgins, he could sleep. As the sounds of the departing steamer grew fainter he settled back, when--”A rending, tearing, slitting sound fell upon my ears. The cher-cher-cher ceased instantly and the house shook as from the convulsive throb of an earthquake.

“The little timepiece on the mantel which had just chimed two trembled, reeled and stopped as if affrighted by the shock. In an instant I comprehended what had happened.

“The Cariboo had blown up!”

Higgins, alas, was right. Just off what’s now Fisherman’s Wharf, the Cariboo had been splintered by an horrendous blast as her boiler erupted. Higgins hastily dressed and ran for the Hook and Ladder Co.’s fire bell but was beaten to it by a young woman. With the bell arousing residents not awakened by the blast, he ran for the waterfront where he met a Scotchman named Wallace.

They commandeered a boat tied to the wharf and rowed for the scene of carnage. the room he made a low obeisance to the chairman and was conducted to a vacant chair at the side of the guest of the evening—said chair having been vacated by one of the company who had found the conviviality too vigorous for his comfort.”

Today’s transmogrified Fisherman’s Wharf at Shoal Point, on the southern shore of Victoria’s Inner Harbour is nothing like it was in 1861 when the steamship Cariboo exploded just offshore. —mustbevictoria.com

“The dim light of approaching day enabled us to disconcern the late fateful craft lying a helpless, misshapen mass and drifting with the tide... A few lanterns were moving fitfully among the ruins. The upper deck had fallen in, and the lower deck had been blown to pieces, but fortunately as the bottom was unimpaired, and as the wreck did not sink it was towed into a little cove and anchored there for safekeeping.

“In the water at the side of the steamer was found the dead body of James Jamieson, the second engineer... Capt. Jamieson had disappeared, nor was any trace of him found for many days when the sea gave up his mutilated form.”

Fraser River pilot Henry Gray had been standing at Jamieson’s side but moments before the explosion but he stepped out of the pilothouse to adjust the binnacle lamp. The next Gray knew, he was standing on the main deck, uninjured, the hurricane deck in splinters about him.

A passenger had been standing beside young James at the boiler, talking. “When the steam and smoke had cleared the passenger found himself near the spot where he stood when the explosion occurred while the engineer had been killed.”

Chief Engineer Allen and Mate Sparks were found in the shattered debris; they’d both died instantly. The body of Higgins’s friend, de Garro, was later recovered from the harbour. All told, seven died in the blast.

“Pieces of the boiler,” Higgins recalled years after, “the iron of which was of unusual thickness, were picked up on the boat and a few fragments were found on the shore. What remained of the shell of the boiler was deposited on the beach near the tragic scene. I saw it lying there 35 years after the tragedy. It was covered with barnacles...”

Engineer Allen was censured at the inquest for negligence, the jury ruling, “the cause of the explosion was too little water in the boiler. When the steam was blown off in vast volumes the boiler was emptied and when the water was turned on it fell upon red hot plates with the natural result.’’

Like the helm of the Fort Yale, that of the Cariboo was found in the water, virtually undamaged. Archibald had had the wheel in his hands at the moment of the blast—as had brother Smith when he was killed. Fate had been even unkinder to Archibald. But days before he’d turned down a handsome offer for his new ship.

Long after the disaster, editor Higgins learned why Jamieson had been late in sailing that morning of Aug. 2, 1861. He’d had “a presentiment of evil and wished to remain in port till the next day”.

But he’d changed his mind and sailed, two and a-half hours later.

Victoria’s last link with the ill-fated Jamieson brothers was their headstone in the Quadra Street Cemetery, today’s Pioneer Square. Sadly, it was removed long ago. The Cariboo was rebuilt and returned to service as the Cariboo Fly.

Such is the remarkable saga of the Jamieson brothers—Andrew, Arthur, Smith, Archibald and James. Five brothers killed in seven years. In all the maritime history of British Columbia and Oregon, theirs is a story without equal.

Five brothers who came to the New World to seek their fortunes as riverboat men. Then there were none.

* * * * *

It never occurred to me that someone would write a musical ballad about the Jamiesons, It certainly never occurred to me that someone would dance a jig during a musical tribute to the five brothers who, in almost as many years, were killed—one, two, three, four, five—in steamboat accidents.

Victoria’s Pioneer Square, the old Quadra Street Burying Ground, where a headstone once honoured three of the Jamieson brothers.

For years, Victoria’s last link with these brothers was a headstone in Quadra Street Cemetery (today’s Pioneer Square) where a headstone, long removed, bore the inscription, “In memory of Baird Jamieson, who lost his life in the explosion of the steamer Yale on the Fraser River, 14th April, 1861. Also Archibald Jamieson, and James Baird Jamieson, who lost their lives by the explosion of the steamer Cariboo in Victoria Harbour, 2nd August, 1861. Three brothers, sons of the late Robert Jamieson, Nrodick, Isle of Arran, Scotland.”

All of which is about as tragic—and romantic—as you can get, and explains folk trio Tiller Folly’s lead singer and composer Bruce Coughlan’’s inspiration to write a ballad to celebrate the misadventures of the ill-fated Jamiesons after reading my book, British Columbia Shipwrecks.The popular Celtic band that specializes in B.C. ballads based upon real-life characters and events performed for the Chemainus Valley Arts Society in October 2008 to celebrate the province’s 150th anniversary.

During an outstanding performance in St. Joseph’s School hall, Bruce Coughlan, Laurence Knight and Nolan Murray gave a rousing and upbeat musical saga of the Jamiesons—so rousing and upbeat that a number of the school’s international students began to dance enthusiastically.

As I listened to Tiller’s Folly and watched the dancers, I was struck by the teens’ odd expression of this musical tribute to the luckless Jamiesons. If only, I wondered, the brothers could have seen their maritime exploits and untimely deaths recounted in story and in song and dance, what would they have thought?