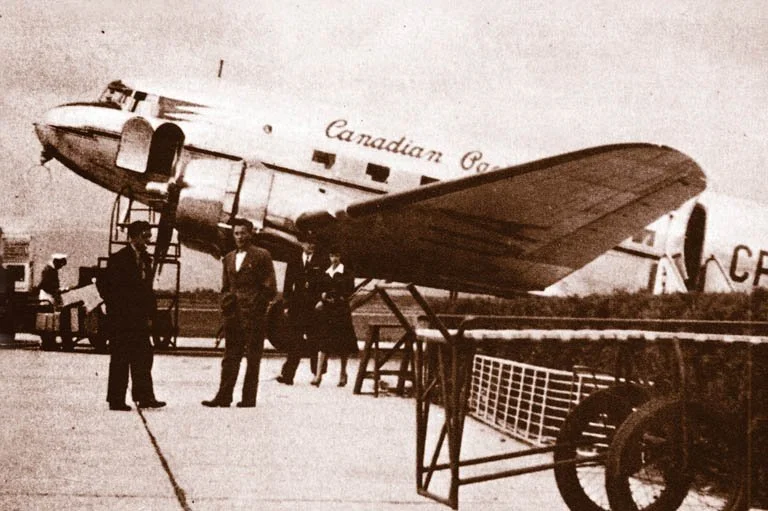

Canadian Pacific Airlines Flight 21

(Conclusion)

Last week, we ended the first instalment with the investigation into what was suspected to have been a bomb aboard CP Air 21 underway...

By this time the on-site examination of the wreckage was declared to be completed upon removal of items of interest for laboratory examination. These included as many pieces of the tail section as could be found having been transported for re-assembly to a vacant hangar at the Vancouver airport.

—Author’s collection

Two weeks after the disaster, RCMP scientists confirmed “traces of an element and a compound that go together in explosives” had been recovered from the washroom. Carbon and potassium nitrate are components of gunpowder, a low-velocity compound which would have had to be intentionally detonated.

What seems to be a minor explosive would be enough to do the job if it exploded in the right place, Dr. Lowell had said earlier.

In what seems to be hair-splitting, it was reported that placement of the explosive, whatever its composition, was critical. Concealed beneath a washroom basin or in a compartment strengthened suspicions of a bomb; but if on the floor of the washroom it could have been detonated by air turbulence. (Begging the obvious question, what was it doing on the floor?)

The continuing headlines about a bomb prompted a representative of the Airline Pilots’ Association, who said he was speaking for himself, to question the sale of flight insurance at airports. Commercial airlines had such good safety records that he didn’t think special insurance necessary; worse, it could prove a temptation to those of evil design.

“People don’t take out a separate insurance policy before getting on a bus or a train,” he said, arguing that checking personal luggage would be too time-consuming although “it would be worth it if it means saving even one load of passengers”.

(This was 36 years before 9/11 changed air travel forever, it should be noted. —TWP)

Ottawa newspaper columnist Gerald Waring, after reciting several close calls he’d experienced while flying, wrote how he’d always been against buying flight insurance, then demanded that the Minister of Transport ban their sales in airports. Citing the suspected bombing of CP 21, he wrote:

“They are an invitation and incitement to every psychotic who dreams of putting a bomb on a plane and taking the insurance company to the cleaners. Maybe he wants to get rid of a wife...or maybe it’s another relative, or a business partner, or even himself. In each case heavily insured through the airport slot machines.”

Insurance dispensed by machine was too easy, he grumbled, whereas buying regular life insurance required scrutiny by the policy issuer. He thought it best that insurance dispensers at airports—“slot machines with their jackpot of death”—be banned. “Pass a law. Root them out. Smash them up.

“Then, I believe, we’ll all fly more safely.”

Five weeks after the CP Air disaster, headlines announced the possibility of a bomb aboard a United Airlines Boeing 727 that disintegrated in a ball of flame over Lake Michigan with 32 persons aboard. Coroner McDonald, already in the U.S. for a coroner’s convention, announced that he was going to fly to Chicago to speak with investigators.

Two days later, a CPA flight between Prince George and Vancouver—another DC-6B—landed safely after reporting engine trouble. Everyone—airline personnel, civil aviation authorities, the police and the flying public—were obviously edgy.

On the positive side, scientists in Washington announced they’d perfected a major tool against airliner sabotage, a machine that could “smell” chemicals exuded by dynamite and other explosives.

In mid-September, just over two months since the crash of CP 21, it was formally announced that a violent explosion had downed the aircraft, that police were pursuing an investigation into how it got aboard and “why it went off”. By then part of the fuselage and the entire tail assembly had been reconstructed and an official public report was promised but no deadline was given.

Yet officials continued to be tread water, Dr. Thomas How, regional DoT director, saying, “...We’ll try to say what caused the explosion, and I think maybe we can. But as to whether there was any criminal intent, will have to be decided by the RCMP.”

“We’re still working on it,” said an unidentified Mountie.

All the while, 25 police officers had continued to wade through swamps and dense underbrush in search of further wreckage. Almost a month to the day, the last truckload of debris was delivered to Vancouver for study.

Recovered and reconstructed in a Vancouver hangar, wreckage from CP Air 21. —Department of Transport

Almost at the same time, a CP Air DC-6B sister of the CP 21 en route to Vancouver turned back to Terrace when a passenger was overheard to mention a bomb. The aircraft was thoroughly searched and the 25-year-old Prince Rupert logger, who was thought to have been drinking, was taken into custody. “He felt pretty foolish,” said an RCMP officer.

nvestigators pulled out all stops in their search for clues. —Author’s collection

By late September, it seemed, no one knew where they stood, in particular Coroner McDonald who was beginning to believe that the cause of the explosion might never be known because there wasn’t even consensus among investigators. The DoT, he complained, were saying it was a bomb; the RCMP blamed aeronautical failure—lighting striking “transistorized material” aboard the plane.

“How can I be expected to know, then, just what did cause that crash,” he asked.

Rather than ending in a whimper, however, the tempo picked up in mid-November when the coroner’s inquest resumed with reports of “two mystery men” walking through the parked DC-6B shortly before loading and within two hours of its crashing.

After CP Air service personnel testified that the aircraft was in normal running order before takeoff, upholsterer mechanic Tom Kelly told of seeing two men with an RCMP officer in the plane. “They were in the galley area of the plane... I asked the constable if I could do anything for him and he said he was just showing his friends around.”

Kelly said he recognized the officer but not his friends. He regretted not having reported the incident, and said the company had since instituted keeping a list “with the ramp officer of all people who are supposed to be aboard [a] plane”.

Several other CPA employees corroborated Kelly’s story which was then defused by the lawyer representing the attorney general’s office: the constable had been identified and could be called to testify if necessary.

There was more drama when a cleaning woman testified to seeing “an odd-faced man” exit one of the aircraft’s toilets just 70 minutes before takeoff. She described him as tall, about 30, wearing a small-brimmed hat. He struck her as “odd because his chin had no corners but was round and there was no cleft in his chin, it receded”.

She’d reported the encounter days after the crash.

The jury viewed the reassembled tail section—5000 torn pieces painstakingly put back together—and heard DoT investigator John Love state yet again that the explosion had occurred in the lavatory wash basin. “It is apparent that nothing from the fuel or heating system[s] or any other system of the aircraft could have caused a blast with that velocity.” Investigators had ruled out anyone having been in the washroom at the moment of detonation and there was no evidence of lightning damage.

Then an RCMP chemist told of black powder stains in four areas near the rear washroom. But, she said, gunpowder gives off dense black smoke and one of the two eyewitnesses had seen “a billow of white silky smoke” emitting from the tail.

She noted that gunpowder was a simple mix of of sulphur, charcoal and saltpetre, and any traces of nitroglycerine would have been washed away by the rain.

A metallurgist with the Pacific Naval Laboratories in Esquimalt then explained a piece of metal recovered from one of the victims who’d been sitting near the back of the plane had contained copper content that appeared to be foreign to the aircraft. Asked if the metal could have been from a detonator he said he wasn’t familiar with metals used in such devices, he could only be sure that the copper shard was unlike any metal used in the plane’s construction.

The tests and testimony went on. Another explosives expert explained that only 33 ounces of gun powder bought at a sporting goods store and carried in a package as small as five inches square was sufficient to cause a blast similar to that which downed the CP 21.

The final witness, RCMP Sgt. Bob Mullock, assured the jury that the force was investigating 52 homicides and would go on until it was satisfied that the “person responsible for the crash will either never be known of that the person responsible for the crash is properly identified”.

He said three passengers remained of interest: professional powder man Steve Koleszar; Peter Broughton, an enthusiastic sportsman who loaded his own ammunition and kept reloading materials in his home; and unemployed Douglas Edgar who lived mostly on gambling and who’d bought $125,000 worth of flight insurance 20 minutes before takeoff, naming his wife, daughter and mother beneficiaries.

Curiously, Edgar had no apparent reason for being aboard CP 21. He’d told his wife he had a job lined up with a new pulp mill in Prince George because he knew a friendly foreman; however, no one there knew him.

The ammunition equipment found in the home of Broughton, said to be “a perfectly normal boy” although something of a loner, was of insufficient strength to do the damage done to the plane.

Of the three, Koleszar stood out because of an extensive criminal record that included “one or two” acquittals of murder charges [in fact, a manslaughter charge; he killed a man in a brawl] and he’d been dishonourably discharged from the army after several courts martial.

(Although not acknowledged at the time, there was a fourth suspect: accountant Paul Vander Meulen, co-owner of a Cariboo gold mining company who was carrying a heavy calibre revolver in his luggage. He’d suffered a head injury several years earlier and been treated for chronic anxiety by a psychiatrist who considered him to be capable of “violent, irrational acts”.)

Which explains the Coroner’s caution to the jury before it retired that they might be ruling on 51 homicides and one suicide although Sgt. Mullock had pointed out that the perpetrator might not have been on board the plane at all.

Late in November, after exhausting testimony, the seven-man coroner’s jury returned a verdict of “unnatural death due to an explosion” and recommended that the investigation continue.

When next the CP 21 made news, late in December, it was as a small notice that Sandor Szonyi was filing suit against CP Air for damages arising from the death of Mrs. Margaret Szonyi and her seven-year-old son Alex. He claimed negligence on the part of the airline.

And, in January, it was announced that the cause of the crash of a TCA jetliner within minutes of takeoff at Ste. Therese, Que., three years before, killing 118, had been narrowed down to mechanical malfunction.

May 1966 – Almost anti-climactically, the Dept. of Transport announced its official verdict of the cause of the crash of CP 21: the “explosion of a device which resulted in aerial disintegration... in the left lavatory in the aft section of the aircraft.

The explosion was of such magnitude that it could not have been caused by a substance native to the aircraft.

“Examination of the wreckage disclosed no evidence of any malfunction or failure of the aircraft, its power plants, propellers, or systems prior to an explosion in the left lavatory. The weather was suitable for the flight and there was no evidence that weather was a factor the accident.

“All available evidence indicates that it was flying at an assigned altitude in straight and level flight in clear weather when an explosion occurred and the aft portion of the aircraft separated from the aircraft.”

Two of the four passengers on the suspect list, Peter Broughton, left, and Paul Vander Meulen, right. To this day, police, who are convinced that the killer also died in the crash, can only surmise who was the real murderer-suicide.—Vancouver Sun

October 1966 – A proposal to ban airport vending machines for in-flight insurance put forward by the Solicitor-General’s office was unanimously referred by the House of Commons to its committee on justice and legal affairs. This, after Ron Basford, the Liberal members for Vancouver-Burrard had asked for the machines’ removal after condemning them as an “invitation to maniacs”.

“Only flight insurance is tailored to mass murder,” he said in introducing a private member’s motion to have the government ban the machines. “There is no reason for us to put temptation for murder and suicide before the public.”

Citing 15 world-wide cases of sabotage since 1945 that had killed 230, he suggested that flight insurance, then available up to $300,000 “in relative anonymity,” be sold only through insurance agencies outside airport terminals which would allow normal vetting processes.

December 1966 – The Canadian Air Line Pilots Association representing 1100 pilots of five scheduled Canadian carriers joined in demanding elimination of airport vended flight insurance in a brief to the Commons justice and legal affairs committee. They, too, presented a history of 11 crashes of 18 since 1949, two of them in Canada, that were known or suspected to be the result of sabotage.

The CALPA was fine with travellers buying flight insurance but they wanted it done through agencies which would require some checking of the buyer’s background.

Deputy Minister J.R. Baldwin told the committee that the DoT was neither strongly for nor against flight insurance sales at airports, having allowed such services to be provided because of a public demand for them. After studying the available information the department saw “no apparent connection between vending machines and sabotage”.

He pointed out that Department figures for 1965 showed that 67,596 policies were sold through vending machines, 321,304 across airport counters, and 9,148 were handled by the airlines themselves. This amounted to about eight percent of the 5,447,440 passengers boarding at Canadian airports during the year.

Baldwin reminded the committee that just a single Canadian air crash, in Quebec, had been proved to be the result of sabotage.

February 1968 – Beneath the small headline, “Air Terminal Insurance To Stay,” officials of Vancouver International Airport declined to remove flight insurance vending machines from the terminal after Liberal MP Garde Gardom (Vancouver-Point Grey) had requested their banning in the legislature. Airport manager William Inglis said there had never been proof of anyone deliberately causing a plane to crash to collect insurance obtained from the Vancouver machines.

November 2015 – Didi Henderson, whose father died in the crash, speaking to the CBC about the extensive investigation: “I can’t help but wonder...what might have been missed or what modern-day forensics could have done differently.”

July 2025 – Wikipedia’s single-page entry on Canadian Pacific Airlines Flight 21 sums up this 60-year-old tragedy in two terse sentences: “No one claimed responsibility and no charges were ever laid. The source of the explosion remains unknown.”

Global News has termed the bombing of CP 21 “one of Canada’s greatest aviation mysteries,” the CBC, “the largest unsolved murder on Canadian soil”.

In 2012, 100 Mile House resident Ruth Peterson was moved to fundraise a memorial plaque where only some tags hanging from a tree marked the crash site. “I visited the site last summer,” she told Global News, “and [couldn’t] believe people didn’t know about it, it should be remembered.”

100 Mile House has grown over the past 60 years but the area of Dog Creek where CP Air 21 crashed remains much as it was in 1965. —District of 100 Mile House

CP 21 was Canada’s fourth worst aviation disaster at that time. Less than two years previously, a Trans-Canada Air Lines DC-8 crashed near Ste. Therese, Que., killing all 118 aboard. A Maritime Central Airways DC-4 carrying 79 crew and passengers crashed into muskeg near Issaidon, Que., and, here in B.C., in 1956, a TCA North Star struck Mount Slesse, killing 62.

CPA’s previous worst crash, with 28 dead, occurred in Alaska in July 1951.

CP 21 was Canada’s second known bombing of a commercial aircraft and, ironically, the second to strike CP Air. In September 1949, 23 people died in the crash of a DC-3 over Sault au Cochon, Que., 40 miles northeast of Quebec City. Among those killed was Mrs. J.A. Guay, a 28-year-old housewife of that city. In the course of investigating all of those aboard, police learned that she intended to divorce her philandering husband and that he’d threatened her.

A photo of the bomb-laden DC-3 minutes before takeoff was snapped by an amateur photographer. —canadashistory.ca

After a taxi driver reported taking “a woman in black” with a parcel to the airport, police tracked down Mrs. Marguerite Pitre who admitted she’d been so distraught that she’d attempted suicide after she learned that the parcel she’d delivered to the airport as a favour to her lover, Albert Guay, was a bomb. He’d told her it contained a statue.

The bizarre plot became apparent when police learned that Guay had had Genereux Ruest, Mrs. Pitre’s brother, also a watchmaker, devise a timing mechanism he placed in a parcel marked “fragile”. He’d convinced his wife to fly to Baie Comeau to pick up jewels for his business then bought a $10,000 insurance policy on her life just before her departure.

Albert Guay, wife Rita Morel in happier times. Divorce was difficult in Quebec in 1949 but, unfortunately, murder wasn’t. —canadashistory.ca

The bomb had been timed to detonate while the plane was over the St. Lawrence River which would have made investigation much more difficult. But the DC-3, running five minutes late, crashed on a hillside.

It was while he awaited the hangman after being convicted and sentenced to death that Guay incriminated Pitre and Ruest. They, too, were executed. She was the last woman hanged in Canada.

* * * * *

—Maclean’s Magazine, Feb. 9, 1966

STREAKY’S LAST RACE

James Roe

Streaky was an elderly champion racing pigeon who belonged to Jim Smith, an Okanagan Valley logger. For five years she survived assaults by mountain eagles, goshawks and falcons who attacked her again and again as she raced across B.C. winning medals for her owner.

Old, tired and wounded by five years of attacks by birds of prey, Streaky was en route by CPA air freight to Fort St. John for her last race before retirement. She never made it. The DC-6B crashed with a loss of 52 human lives after a mysterious explosion ripped the aircraft apart in mid-flight. Somewhere in the smouldering wreckage, Streaky perished too.

Smith and his family were heartbroken. “No matter how late Streaky was,” says Smith, "the children would come running in with news of her arrival just as if the old girl had broken the sound barrier.”

Last fall he lodged a claim with CPA for Streaky's loss. He asked $300 damages, but so far all he's got are a number of polite letters. “I felt a little awkward about claiming for a pigeon when so many humans were killed,” says Smith. “But there aren't any more like her around—she was just like a real person to us.”

* * * * *

Cy Leland, the DoT’s lead investigator in the crash of CP Air 21, is second row centre. —Dept. Of Transport