The Fight for the Standard

During a recent tour of Victoria’s beautiful Ross Bay Cemetery, Old Cemeteries Society guide John Adams pointed out the headstone for onetime U.S. Consul Allen Francis.

Coincidentally, in his latest bestselling book, Untold Stories of Old British Columbia, friend and fellow historian Dan Marshall pays tribute to a mutual hero of ours, David Williams Higgins, whom I’ve introduced to Chronicles readers on several occasions.

There’s a strong and fascinating connection between Francis and Higgins.

During the 1860s, the time of the American Civil War, Francis served as Consul in Victoria where and when Higgins worked as a journalist. In these professional capacities, their paths often crossed.

Perhaps surprisingly to us today, their connection was that dreadful conflict then raging below the border. Supposedly neutral Victoria was a hotbed of Northern and Southern sympathizers. Besides open rivalry and occasional acts of violence, there was a conspiracy by the pro-Confederates to outfit a privateer with which to hijack a Federal payroll ship—even a plot to kidnap Consul Francis.

One of the worst civil wars in history began with the firing by Confederates on Fort Sumter, in South Carolina's Charleston Harbour, on April 12, 1861. Hostilities soon spilled over the U.S.-Canadian border, particularly in western outpost Victoria. —Currier & Ives print, Wikipedia

Francis and Higgins were in the very midst of this years-long turmoil.

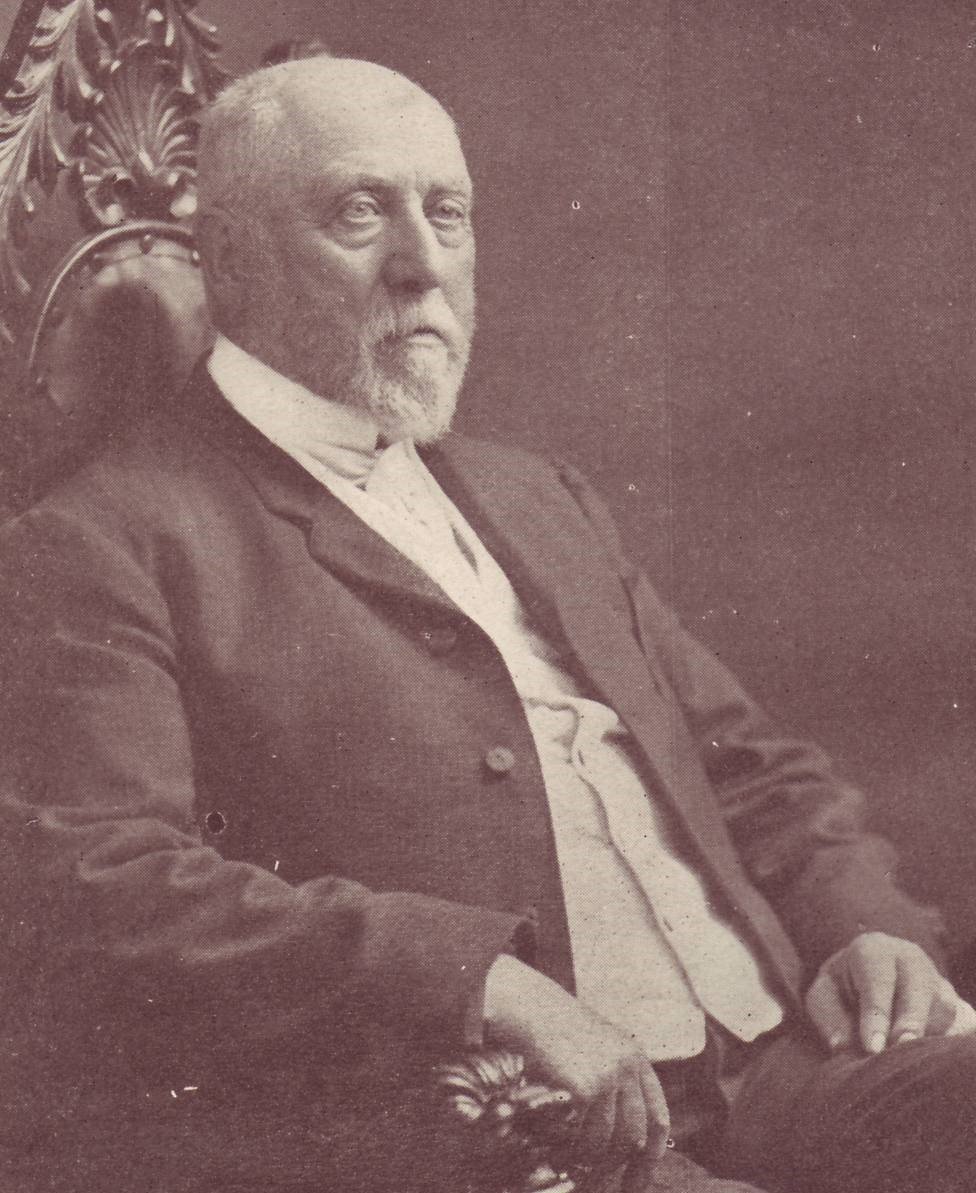

D.W. Higgins has been called western Canada’s Bret Harte. Certainly, he’s one of its greatest storytellers because of his unique experiences during the 1858 Fraser River gold rush, as a journalist and, finally, politician. —Author’s collection

It was Francis’s duty to do everything in his power to protect the interests of his government; it was Higgins’s job as a reporter to keep his eyes and ears alerted to the undeclared war going on in the streets of Victoria.

Forty years later, Higgins published two books of reminiscences, Mystic Spring and Passing of a Race, in which he recounted some of the most remarkable events and characters he’d witnessed and known during his career as both a journalist and a politician. In retrospect, his chapter entitled “The Fight for the Standard” comes across as being almost comical.

In 1860, it was anything but. Passions were fever-hot on both sides; violence simmered just below the surface, checked only by the reality that both Northern and Southern sympathizers were on British soil.

With minor editing, here’s Mr. Higgins’s tale of that exciting and all but unknown chapter in Victoria’s history.

* * * * *

His name was William Shapard. He was a Southerner by birth and a house carpenter by trade. He came to Victoria in 1858. He was in his prime and laboured diligently at his calling till the war between the North and South broke out. Then he laid down his tools and took to talking about the wrongs of the South and the right of the Southerners to secede and buy and sell [slaves].

There were many here who sympathized with him, and in a short time our little city was filled with Southerners who fled hither to escape conscription or conspire for the overthrow of the Republic. A good talker like Shapard—a keen, active and aggressive person such as he was—attracted the attention of the newcomers and he was soon the centre of a group of men and women who formed the Southern colony.

But talking brought no grist to the Shapard mill—put no bread in the little Shapards’ stomachs, pants on their legs or shoes on their feet.

Neither did it furnish the parents with presentable clothing or pay their house rent. Shapard, who was a high-spirited fellow, would neither beg nor borrow, and the grass in his pasture soon became very scant. Work he could not while his beloved South was in peril, and he could not cross the line and enter the Southern army without consigning his wife and children to want.

At last he hit upon a scheme the adoption of which he hoped would ensure him at least a living. He hired a small brick building on Langley [Street] near Yates Street and opened...the “Confederate Saloon." In front of the saloon he erected a lofty staff, and from the top of the staff he flung to the breeze a Confederate flag.

This flag was made by the Southern ladies of Victoria and their sympathizers and by them was presented to Shapard.

As well as I can remember, the flag represented a Saint Andrew's Cross in Blue on a red ground. Within the lines of the cross were 13 stars, each star being emblematic of a seceding state. The pet name of the flag was the “Stars and Bars". Many people regarded 13 as an unlucky number, and predicted the failure of the Confederacy in consequence. But the retort, always ready, was that the states which rebelled against the British Crown in 1776 were also 13 in number and they won.

It is a poor rule that will not work both ways, and the Southerners, taking heart of grace from this historical example of their forefathers, continued to struggle with great determination and bravery.

The Confederate Saloon became famous as a rendezvous for the Southerners and the bon vivants of other nationalities. It was noted for its generous free lunches, its excellent rye whisky cocktails and its reading room. It also became noted as time ran on for its poker games. It was said that large sums were staked and lost on its tables by Cariboo miners and Southern refugees who were gathered at Victoria and made Shapard's house their lounging place.

Victoria in the 1860s was a hotbed of intrigue because of the neighbouring American Civil War. —Author’s collection

Every morning at precisely 9:00 mine host of the Confederate would hoist the defiant emblem, and every evening at sundown he would lower it, and folding it carefully away would lock it up overnight.

“You see," he explained, "I have to be awful careful of that bit of bunting. It's merely lent to me by the ladies at this place. I am pledged to return it to them when our cause is gained, and they will send it to Jeff. Davis as a memento of how we kept the fire of nationalism a-burning on a foreign shore. If I were to leave it out after dark some of these cerulean Yanks will steal it and then where should I be? I'd be disgraced forever. "

The presence of the flag was a constant source of annoyance and anger to loyal Americans here resident, and many were the plans laid to capture it, but a long time elapsed before an opportunity was presented. Mr. Francis, the American Consul, was often appealed to by his compatriots, but he advised them to keep cool and bide their time.

Mr. Francis was apparently a very ingenuous character, but the man who picked him up for a fool ran a chance of being fooled himself. He was always on the alert—keen and watchful. To talk with him you would think his mind on most subjects was a blank. He could disassemble better than any other man I have ever met.

The BC Provincial Archives has this photo of Mrs. Francis Allen, wife of the U.S. Consul in Victoria, but not one of her husband. —BC Archives

You could never apparently excite in him the slightest interest in anything concerning the plans of the Southern colony.

To use his own expression, he never “enthused," and yet all the time he was storing away the information in his memory and preparing it for use when the time for action arrived. The Southerners always regarded Mr. Francis as an easy-going nobody, but in the result we shall see how little this estimate of his character was justified.

* * * * *

The summer of 1862 passed away and the long winter evenings had set in. The Southern colony grew and the Confederate Saloon did a roaring business—seven days in the week with nights thrown in.

The place was never closed, and the Confederate standard continued to whip the breeze from 9:00 a.m. till sundown each day. My office was just back of the saloon, and my duties frequently forced me to remain out of bed until 3:00 in the morning. I was always received by the guests with cordiality, and many matters concerning the plans of the colony to fit out privateers, or seize Mr. Francis and send him away on a schooner, were talked over in my presence.

Of course, I never repeated what I heard there, but I did resolve that I would go to any extreme to prevent a personal injury or indignity being inflicted upon or offered to my friend the Consul. Fortunately, the occasion never arose, and I was spared the pain of revealing what I heard...

These are the Stars and Bars that we recognize today as the flag of the Confederate States of America. The “standard” described by Higgins looked nothing like it. Note the 13 “unlucky” stars.—thedixieshop.com

The Confederate flag continued to flaunt its bright hues in the face of the Unionists and the Confederate Saloon continued to enjoy an enormous patronage.

Shapard waxed fat and sleek and grew more defiant than ever before. The union sentiment was outraged by the success of the secession movement, and when the news of Stonewall Jackson's untimely death came and the Southerners went about the streets with crape on their arms and the flag over their shoulders and the standard drooped sadly at half-mast, the Northerners held a quiet little meeting and decided that something energetic should be done to get rid of the rebel standard.

A frequent visitor to Victoria was one Tom Stratton, a native of one of the Eastern States and another outspoken Unionist. His home was at Port Angeles. Stratton was the possessor of a jet-black glossy beard of great length, of which he was justly proud, and which he passed much of his time in stroking and smoothing with his hands.

Tom was a daredevil, and being glib of tongue he frequently indulged in a wordy clash with the Southern residents. To him the flag was a source of great annoyance, and he sometimes made threats as to what he would do with it if he ever got a chance.

One day he told Shapard that if he could steal the flag he would die happy." Yes," said Shapard, "if you should steal that flag you will die, but whether happily or not I can't say. At any rate, the flag when you steal it shall be your shroud.” Stratton made no reply, but stroked his beard and walked off.

Early one afternoon five or six young men, strangers, entered the Confederate. The were professedly Southerners and boisterously cheered for Jeff Davis and the Southern cause. All were possessed of much cash and treated the landlord and all in the house to liberal potations of champagne at $5 a bottle. A poker game was in progress at one of the tables, and the strangers staked heavily and lost with a good grace.

Every time a fresh bottle was opened Shapard was invited to “have another,” and it was not long before he showed the effects of the frequent draughts in speech and gait. The treating continued and when the hour arrived for lowering the standard Shapard was unmistakably intoxicated.

Whenever he made a movement to go outside for the flag one of the young fellows would invite him to “have another," and at last he sank down at one of the tables and fell asleep.

Late in the evening Shapard awoke and, remembering his flag, walked to the staff to lower it, when to his consternation and grief he found that the emblem of secession had disappeared, and with it had gone the gay young strangers who had been so liberal with money and wine. The excitement among the Southerners was great and a heavy reward was offered for the recovery of the flag, but it was never found. It was delivered to the American Consul by the captors and by him sent to Washington.

Some weeks after the disappearance of the flag Shapard entered Ringo's Hotel...on Langley Street. Seated at one of the tables was Tom Stratton, sleek and handsome and carefully grooming his long black beard.

The moment Shapard's eyes fell up on Stratton he took fire. He advanced to the table and poured forth a volume of ugly words. Stratton laughed in his face, Shapard continued his abuse. “You stole my flag!" he foamed.

“Well, what of it?” asked Stratton, as he rose to his feet.

“That's what of it,” screamed Shapard as he dealt his hated antagonist a blow full in the face.

Stratton retorted with a blow and then the two men clinched.

Both were strong and in the full vigour of life, and as they struggled and pounded each other with their hands and teeth their anger found vent in savage growls and yells that resembled more the snarls of wild beasts then the voices of men.

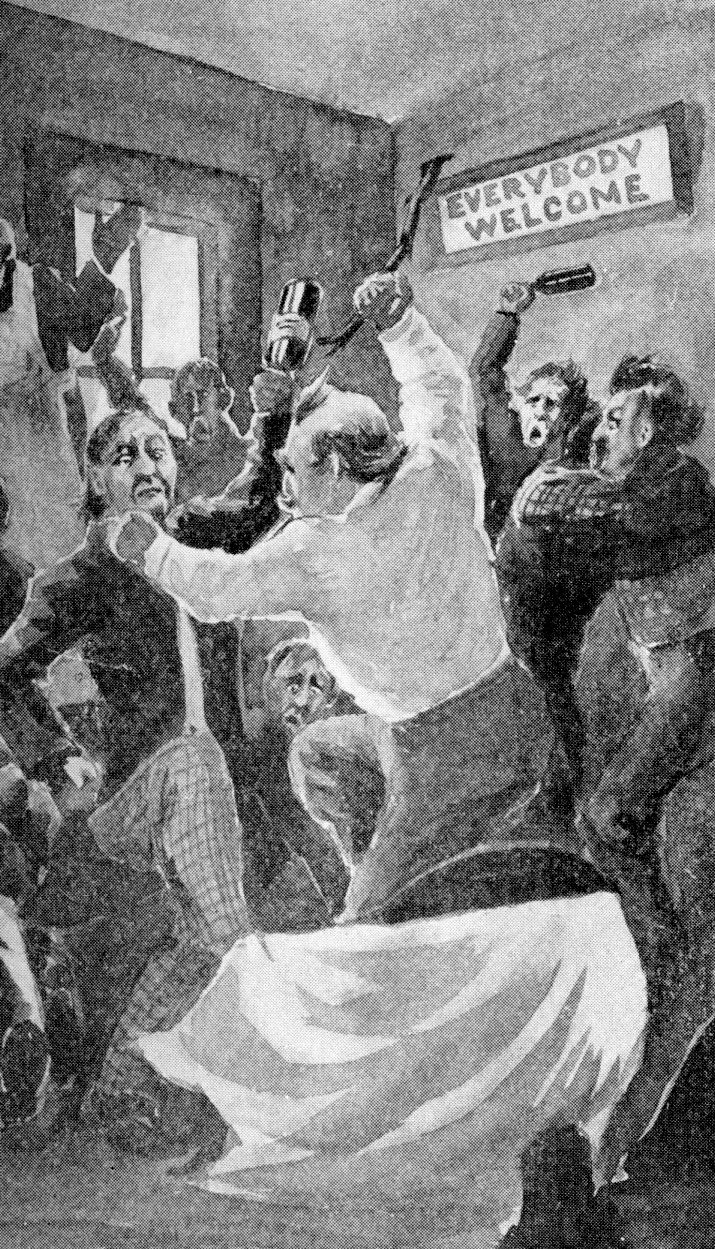

With a roar of rage, Shapard leapt on Stratton and the fight was on. —The Mystic Spring

Over one of the tables Stratton was forced and went to the floor with a crash. In an instant, Shapard was upon him, his knees on his chest and his thumbs pressed into his neck. Stratton's eyes and tongue protruded, but with a herculean effort he contrived to throw Shapard off and forcing him to the floor made him the “under dog in the fight."

Both were by this time covered with blood and their coats and shirts hung in tatters. Stratton's glorious beard had been plucked from its roots and Shapard held it like a plume in his left hand, while with his right he pummelled the body and face of his antagonist, who returned the punishment with interest.

The fight continued for some 10 minutes.

Tables and chairs were overturned and broken, crockery smashed and food and dishes scattered all over the place. The two men were most deplorable spectacles. At last Shapard yielded and Stratton claimed the victory. But it cost him dear. He never was a well man again. His beard never grew again and in a few years he died on the Sound.

Shapard's business fell off after the war and he went to California, after which I heard of him no more. It transpired that Stratton [and another Northerner named Wolfe] stole the flag while the young strangers, who were well supplied with American government money, got the landlord so drunk that he forgot to lower the emblem before dark.