The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, Women’s Style

This week, it’s the turn of The Good - The Miner’s Angel whose name was synonymous with warmth and generosity in every mining camp from Mexico to Alaska.

* * * * *

Nine years ago, Victoria's old Cemetery Society established a special Nelly Cashman Fund to raise money for a centennial stone to be placed on her grave in Ross Bay Cemetery. “Nellie Cashman deserves our recognition,” the Society’s Patrick Perry Lydon and Donna Chaytor told the Times Colonist.

Nelle’s ‘retro’ headstone in Ross Bay Cemetery. —Author’s photo

Who was Nellie Cashman?

I've mentioned her from time to time in abbreviated form in the past but this week’s Chronicle is a full-depth look-back at a remarkable woman whose exploits, like her heart, were bigger than life.

Although records differ as to the date of her birth, her arrival in the New World, even to the colour of her hair, on one fact all heartily concur: that her heart was as large as the Great American and Canadian West she conquered with her ever-cheerful smile, her indomitable courage and her hand outstretched to any man down on his luck.

A Florence Nightingale to miners from Tombstone to the Klondike, when she died in the Victoria hospital she helped to establish, husky, bearded men wept unashamedly for their tiny saint of half a century, Nellie Cashman.

According to one account, the future Miner’s Angel landed in Boston in 1847 at the age of three, sent by her widowed mother in famine-stricken Ireland to be raised by an aunt. Young Nell learned to look out for herself, and others, early. Twelve years later, she was raising four orphaned cousins. For the rest of her active life, in some way or another, loved one and stranger, Nell cared for anyone in need.

She began setting records early, too, when, aged 16, she became a bellhop in a Boston hotel to support her family. Some believe she was the first female to hold this job but, unlike her later feats, this one is unconfirmed.

Young Nell Cashman. —Author’s Collection

Besides tending her aunt's children, Nell was able to save enough to bring her mother from the Emerald Isle. It was then she decided to answer the call of adventure, a call she'd heed for almost 50 amazing years.

Across the Isthmus of Panama to San Francisco trekked the 28-year-old Nell; from there she set out for the rip-roaring mining towns of Nevada to work as a cook, storekeeper and to open what would be a series of restaurants. Charging a dollar for her soon-to- be famous meals, her establishments were immediately popular with miners who struck a chord with Nell.

She realized that these men were of her own kind: always hoping, always seeking that pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.

Saving enough to buy a grubstake, she trudged into the wilds with pick, shovel and pan. At first her husky neighbours laughed at the determined young woman. But scorn soon gave gave way to respect and Nell was accepted into the fraternity of eternal hope.

She’d follow this elusive trail of wealth—sometimes with success—to the end of her days.

It was back in San Francisco that she decided upon British Columbia. Actually, her decision was made by the flip of a coin. With six other disheartened prospectors, she tossed to see where they’d try their luck next. Heads, they’d go to South Africa, tails, to British Columbia.

The $20 gold piece winked tails: it was off to B.C. In that summer of 1874, the noisy troop of six spirited, boisterous miners and sedate five foot, three-inch redhead landed in Victoria, en route to the diggings at Dease Lake. While in Victoria, Nell heard that Cassiar miners were suffering from scurvy. Hiring six men to haul her supplies to open a hotel, she included in her cluttered inventory lime juice and fresh vegetables.

The rugged Dease Lake country. —BC Government photo

By steamer, the expedition headed north to Wrangel, to follow the frozen river to Dease Creek. From there, they struck up-river through snowdrifts and sub-zero temperatures, Nell, in snow shoes, gamely towing a sled with 200 pounds of supplies every inch of the way—160 miles for 77 days.

Asked years after whether she'd been afraid of being the only woman on that hazardous journey, Nell had chuckled, “Bless your soul, no, I have never carried a pistol or a gun in all my life. I wouldn't know how to shoot one. At one time for two years I was the only white woman in camp. I never have had a word said to me out of the way.

“The ‘boys’ would sure see to it that anyone who ever offered to insult me could never be able to repeat the offence. The farther you go away from civilization, the bigger-hearted and more courteous you find the men. Every man I met up north was my protector, and any man I ever met, if he needed my help, got it, whether it was a hot meal, nursing, mothering, or whatever else he needed.

“After all, we pass this way only once, and it's up to us to help our fellows when they need our help."

One of the adventures on the trail had been the night her companions erected her tent on “a steep hill where the snow was 10 feet deep. The next morning, one of my men made a cup of hot coffee and came to where my tent was... It had snowed heavily in the night...night, and to his surprise, he couldn't find [my] tent.

“Finally, they discovered me a quarter of a mile down the hill, where my tent, my bed and myself and all the rest of my belongings had been carried by a snow slide. No, they didn't dig me out; by the time they got there I had dug myself out.

“We finally reached our destination, and I put off running my hotel until I had nursed a lot of the sick miners back to health. Word went out to the nearest military post [Wangel] that I had cashed in my checks. The commanding officer sent a detail of soldiers in to get my body and bring it out to the post. It was a mighty nice thing for them to send clear to there to get my body so I could have [a] Christian burial. I appreciated it, and got those soldiers the best feed they ever had.”

Actually, the officer’s concern had been for her mental health; any woman who’d hike 200 miles through northern wilderness in the dead of winter had to be mad, he thought. But when the rescue party found Nell “cooking her evening meal by the heat of a wood stove fire and humming a lively air, so happy, contented and comfortable did she appear that the ‘boys in blue’ sat down and took tea at her invitation and returned without her”.

Nell hiked out that fall to spend winter in Victoria. While there, she learned that St. Joseph's Hospital was being built. Back at Dease Lake with the spring thaw, she canvassed the miners for contributions and collected a respectable sum.

Nell canvassed the miners for donations towards building St. Joseph’s Hospital in Victoria. —Author’s Collection

The following autumn, she again hiked down to Wrangel, intending to spend winter in Victoria. But while in the Alaskan port she heard that a group of prospectors also heading down river had been stricken by scurvy. With medicines and spruce bark, the indomitable colleen raced back up the Stikine. When all finally reached Wrangel, the miners said Nell saved their lives.

In 1876 Nell heard tantalizing rumours of a fabulously rich strike in Arizona. It was all the prompting she needed. Packing up her few possessions and what money she'd saved, she headed for Tucson, to open the Delmonico Restaurant. In her free time, she tried her hand at prospecting but with little success and, within the year, she was off to Tombstone. It would be her home, off and on, for 20 exciting years.

By then she was almost penniless, her savings having gone to help the needy. “Her principle [sic] business was to feed the hungry and shelter the homeless, and her chief divertisement [sic] was to relieve those in distress and to care for the sick and afflicted,” praised John Chum, editor and friend.

She wasn't long in the lawless camp when she heard that a miner had broken both legs. Hands extended, she canvassed the town, visiting every establishment respectable and otherwise, until she’d raised $500 for the ailing man. Then, once her restaurant and general store were established, over the following years, she stole time from home and business to explore the surrounding region.

Gold, silver and copper strikes attracted her and whenever she found a likely camp she'd open a restaurant. When the local diggings petered out, she’d move on to the next camp or back to Tombstone for a while. Among her famous clientele where the Earps, the Clantons, Doc Holliday, Johnny Ringo and Pat Garrett.

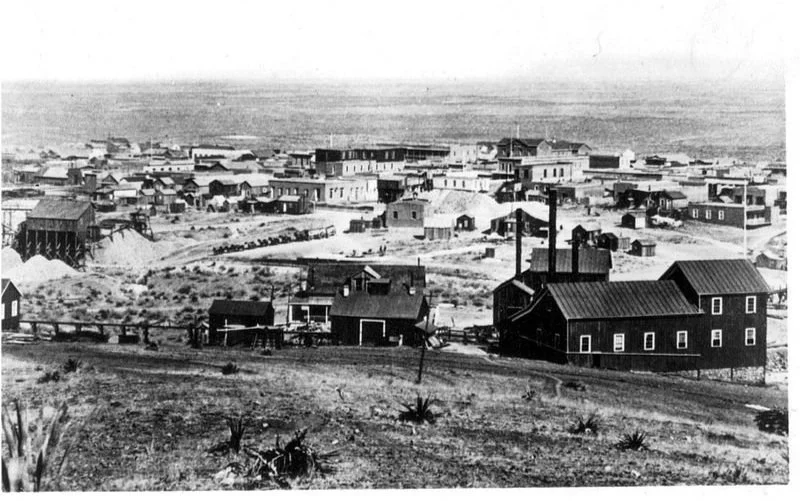

Tombstone, Arizona, about 1881. Thanks to Nell, it had a Roman Catholic church. —Wikipedia

Nell’s attention had early been drawn to the fact Tombstone boasted 50 saloons and “nary a church”. The result was a one-woman campaign that saw the Sacred Heart Catholic Church open its doors, Feb. 1, 1881.

Then she noticed that Tombstone lacked a hospital. Her answer was to journey to Tucson and return with three nuns to serve as nurses. And Tombstone had its hospital.

When miners struck the town’s three leading mines in 1884, Nell heard that the outraged minors were going to lynch the superintendent of the Grand Central Mine, Edward B. Gage. Nell had an answer to that problem, too. Hiring a horse and buggy, she smuggled the frightened Gage to a nearby town. When the lynch mob called on the intended victim, to find he was safely on route to Tucson, they dispersed and the crisis passed.

By the mid ‘80s, Nell and her family were following the rainbow again: Montana, Wyoming, back to Arizona, then Oregon and Washington, then back to Arizona once more. In 1889, she was talking of diamonds in Africa but ended up in the more promising gold fields of California. More years passed, Nell ever on the move. Idaho and even Mexico hosted the indomitable Irish adventurous.

Sometimes, she was lucky, her mining ventures helping to keep her family going. Any extra money was spent on anyone who needed nursing, a hot meal or a grubstake.

February 1898 saw Nell back in Victoria, staying at the Burns House. The fabled trail of ‘98 was in full swing and Nell was to be part of it. She was in her 50s but this fact mattered little to Nell. She joined the mad rush through killing snows and untold hardships through the infamous Chilkoot Pass to Dawson City, lugging her own gear and supplies—20 gruelling trips as one of a human chain that struggled up the Chilkoot Trail, then back down again for more goods and another go.

At Dawson she opened another restaurant, again calling it the Delmonico. Her fare was as popular as ever. Because provisions were almost impossible to obtain, “meals ran anywhere from two to three to five or six dollars. At that, I didn't make any fortune. Part of the reason, though, was because if a young fellow was broke or hungry, I would give him a meal for nothing.”

She spent seven years in Dawson, the Old Cemetery society's Patrick Lydon and Donna Chaytor noting several years ago in the Times Colonist that, besides operating her restaurant, “she was active in mining and as usual very involved in charitable work and helping the sisters of St. Ann with donations to St. Mary's Hospital in Dawson City.”

More hectic years came and went, Nell sneaking prospecting trips into her crowded schedule and always hoping for that lucky strike. When Dawson began to slow, she settled in Fairbanks, Alaska. Then it was off to the distant wilds of Tanana and Koyukuk, to claim the most northerly mining property on the continent.

Nell made 20 gruelling trips over the Chilkoot Summit, carrying and dragging her gear. —Wikipedia

Before leaving Dawson, Nell had made the best strike of her career, No. 19. Years later, she recalled, “It proved to be a rich claim. I took out over $100,000 from that claim. What did I do with it? I spent every red cent of it buying other claims and prospecting the country. I went out with my dog team or on snowshoes, all over that district looking for rich claims...”

After moving to Fairbanks in 1904, she opened a grocery store and “made $4,000 the first winter. In 1907, I went to the Koyukuk district. I had a funny experience going down the river on a raft. I went with an old sourdough. If you know anything about that river you know how many rocks there are in the channel and how swift the rapids are. At any event, coming down through some swift water, we struck a submerged rock that wrecked our craft. All we had left were the two cross-pieces and the two outside logs.

“Sure, we got to shore all right, and fixed up the raft and went on. There was always something interesting happening. You never quite know what's going to happen next, or when your time will come to cash in your chips. It all adds interest and variety to life.”

But the end was nearing at last for the amazing colleen whose name had become synonymous with warmth and generosity in every mining camp from Mexico to Alaska. In 1924, at the age of 80, ‘Miss Alaska’ mushed 750 miles to Seward!

“From the farthest north mining camp to New York City is her trail trip this time, and any obstacles that surmount the trail between here and New York might just as well get out of the way for she’s hit the trail and is going through!”—1924 newspaper.

But, this time, Nell faced tougher obstacles than snow or river rapids: pneumonia. Upon reaching Victoria, she was met at St. Joseph’s, the hospital she’d helped to establish so many years before, by Sister Mary Mark, the supervisor, and Dr. W.T. Barrett who’d “performed lifesaving abdominal surgery on Cashman in St. Mary's Hospital in Dawson City in 1902”.

A newspaper noted that she “scorned to be carried in, but walked on her own two legs into the ward”. It was her last shot. Days later, on Jan. 4, 1925, Nelly Cashman “cashed in her chips," as she’d have put it. The trail that had spanned more than half a century and half a continent had finally come to an end.

Just before the last, Nell had been asked if she wished her body sent to relatives. No, she replied with the old determined fire in her eyes. She wanted to be buried in Victoria, that her tiny estate might be put to better use aiding the poor.

—Author’s Photo

This is the incredible woman for whom Victoria’s old Cemeteries Society established a special Nelly Cashman fund to raise money for a centennial stone to place on her grave in Ross Bay Cemetery.

This is the incredible woman who’s The Good in this trilogy, The Good, The Bad the The Ugly.