The Man With the Touch of Gold

If there is a single name that is synonymous with lost treasure in British Columbia that would have to be Neville Langrell (Bill) Barlee, school teacher, politician, entrepreneur, environmentalist, historian, writer, publisher, prospector and treasure hunter extraordinaire.

By all appearances, he scored at almost everything he did or touched.

Bill Barlee died in 2012 in his 80th year after a lengthy illness. But his legacy, on television re-runs and in the printed word, lives on.

I could cut to the quick and tell you about Bill's mostly successful treasure hunts as well as the one that got away. But that wouldn't tell you much about the man himself and how it came about that he spent the best of his adult years chasing (and finding) pots of gold at the end of rainbows.

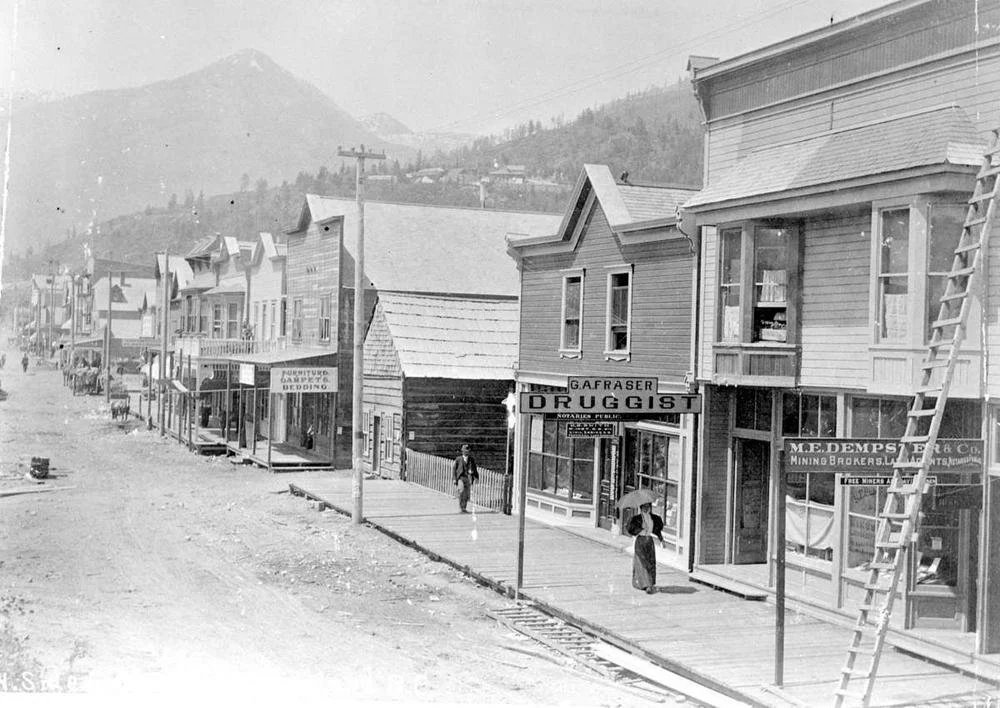

The only abandoned mine I got to explore as a kid was an exploratory shaft, maybe 50 feet long, on Mount Douglas (Pkols). Here, a young Bill Barlee, second from the right, his brothers and friends play with a discarded ore car in his hometown of Rossland, B.C.

Simply: Luck/fate played a hand right from the start, Bill having been born in the famous mining town of Rossland, home of the LeRoi Mine which once had been the richest gold mine in the country. What a place to grow up in, in the 1930s and '40s!

Rossland had long peaked as a boom town by then but much of its mining past survived in a semi-derelict state and as a playground for Barlee, his brothers and those of their chums who shared their passion for the past. It was like living in the Old West, he told Richard Litt in a 1992 interview in the Times-Colonist.

“When I was a boy many head frames of the old mines still stood stark and proud...” With his three brothers he explored some of these once-famous mines; besides the LeRoi there were the Red Mountain, the Nickel Plate and the Red Star.

Deep down inside the fabulously rich Le Roi Mine. Unlike abandoned coal mines which are prone to cave-ins and gas, hard-rock mines are reasonably safe to explore—if there are no deep, water-filled holes to step into, or pockets of ‘dead air’ that are lethal. Bill Barlee likely explored some of these workings as a kid. —BC Archives

He'd never forgotten the eerie stillness of a ghost town and the echo of his footsteps on long disused boardwalks that had known the tramp of 10s of 1000s of miners' feet in better days.

Although ghost towns and abandoned mines had to give way to other things—by his teens, his family was living in Kelowna, and he'd become active in sports—the history bug had been firmly planted. Even when he became a high school physical education teacher, he taught history on the side. Athletic himself, he was active in hockey and lacrosse and set a regional record for running the mile that was unbroken for 20 years; he won the Okanagan Valley tennis singles seven times and the doubles, with his good friend Ronald Swartz, 13 times.

Even in later years he was able to “trounce” tennis players 30 years his junior.

By then married and the father of four daughters, and after his first, unsuccessful run at being elected to provincial office, his simmering passion for history finally found expression. Taking an unpaid leave of absence from teaching, he founded Canada West magazine, devoted strictly to western frontier Canadian history. He began with seven subscribers; within a few years he had 4000.

That was enough for him to quit teaching and to devote himself to publishing stories about British Columbia's exciting past.

He became famous of sorts for his policy of not selling subscriptions below the border; not because he was anti-American but because he'd learned that some Americans who'd already ransacked historic sites in their own southwestern states, were using Canada West to find new fields to plunder.

That was possible because Barlee was writing about the ghost towns and mining camps that had intrigued him since childhood. His next publishing venture, in 1969, was a book whose title said it all: Gold Creeks and Ghost Towns. In his own words, it became a runaway bestseller, more than 100,000 copies sold as of 1992. It's still in print.

He soon followed up with another bestseller, The Guide to Gold Panning, whose publication—Barlee's Midas touch at work again—coincided with the long-fixed price of gold being allowed to float at market value—from $35 an ounce to 100s of dollars an ounce. Prospecting became the craze for anyone with a vehicle, a Free Miner's License, a gold pan and a strong back.

“My books disappeared off the shelves like hotcakes,” he told interviewer Litt.

By this time comfortably off, he made a second run for MLA, again to be defeated, but by a much smaller margin. That out of the way, at least for the time being, he continued to go prospecting, not just in print but in fact, by researching then exploring the creeks of the Cariboo, the Boundary Country, Similkameen and the Tulameen.

These expeditions were like busmen's holidays—work but mostly fun, and often with a respectable return in dust and nuggets.

The stately Fairview Hotel aka the Big Teepee, where Barlee and friend struck pay dirt for the first time. —Wikipedia

Without even a metal detector, just a screen and shovels, he and partner Cyril Murray struck pay dirt at the site of the Hotel Fairview, in the ghost town of that name, in the dry Okanagan southland. Barlee was looking for a story not gold, that first trip in the spring of 1969. There was little more than sagebrush plain to be seen but his keen eye soon detected the outline of city streets, then foundations and cellars. From his research he knew that the three-storey hotel, once famous as the Big Teepee, had been on the east side of town, and they soon found its hollow outline.

Sand and shards of melted glass and unfilled-holes from previous half-hearted attempts by fellow treasure hunters covered the site.

They decided to return with their own 1/4-inch mesh screen a week later when, methodically, they measured off in squares and set to work. Within minutes, they made their first find, a fire-charred 1872 Canadian quarter. More silver coins quickly followed. Then a gold wedding band, still shiny as new.

By the end of an hour they had a Sterling silver watch chain, a gold brooch, four silver nuggets, two silver cuff links, a diamond ring, a second gold ring and 27 coins, mostly silver. More treasures, including a gold watch, followed as they returned again and again.

All this with just a screen and shovels. In total they recovered 150 articles of interest and value.

Columbia Avenue, Rossland. Note the boardwalks beneath which, years later, Bill Barlee searched for coins and tokens. —BC Archives

Long before Fairview, Barlee had recovered coins from underneath boardwalks in his home town of Rossland. It occurred to him that the miners must have dropped their change on Sandon's boardwalks, too, and he screened the boarded-over soil from in front of the Virginia Block. In 50 feet of boardwalk he recovered 100 coins (most of them in mint condition, no less) and tokens from the 1880s through the 1950s.

These treasure hunting forays also provided more fodder for more books: Similkameen: the Pictograph Country, and Historic Treasures and Lost Mines.

After all, who better to walk the talk than Bill Barlee!

He ultimately did succeed in winning a seat in the provincial legislature as an NDP candidate for Okanagan-Boundary then as served as a cabinet minister. Some yet believe he was the best tourism minister ever. (He explained his membership in the NDP—his demonstrated entrepreneurship almost a philosophical contradiction—as simply having a social conscience.)

With a subsequent change of government in 1996 (he lost by only 27 votes) he was back to prospecting and publishing full time. And producing with Mike Roberts, a popular Sunday morning CHBC television program, Gold Trails and Ghost Towns that ran 1986-1996 and which can yet be seen in re-runs. Props for the shows—some of them priceless antiquities—came from Barlee's own collection in his Canada West Museum in Penticton.

The artifacts he'd amassed over the years were valued at three-quarters of a million dollars at the time of his interview in 1992. Some of his artifacts were of such historical interest that they were borrowed by the Museum of Civilization in Ottawa.

Bill Barlee wanted to not just find 'lost treasure' in the form of British Columbia's relics and artifacts but to save them for posterity.

When he was again profiled in the Times-Colonist, in 2001, it was because he'd published his biggest book yet, all of 352 pages and in hardcover. Like the others, it was about ghost towns and treasure trove in British Columbia's south-central interior and based on the wealth of information he'd gathered over the years through archival research, interviews and firsthand fieldwork. He was lucky again in that many of the people he was able to interview were by then in their high 80s and 90s and time was running out for their memories and experiences to be recorded for posterity.

He was still cursed by the paradox of informing people of the province's historic sites while aware that some unscrupulous collectors were looting them blind: “One person took a boxcar and a half of relics out of Sandon, and someone else looted Phoenix.

“Those were the two most important ghost towns in the Interior.”

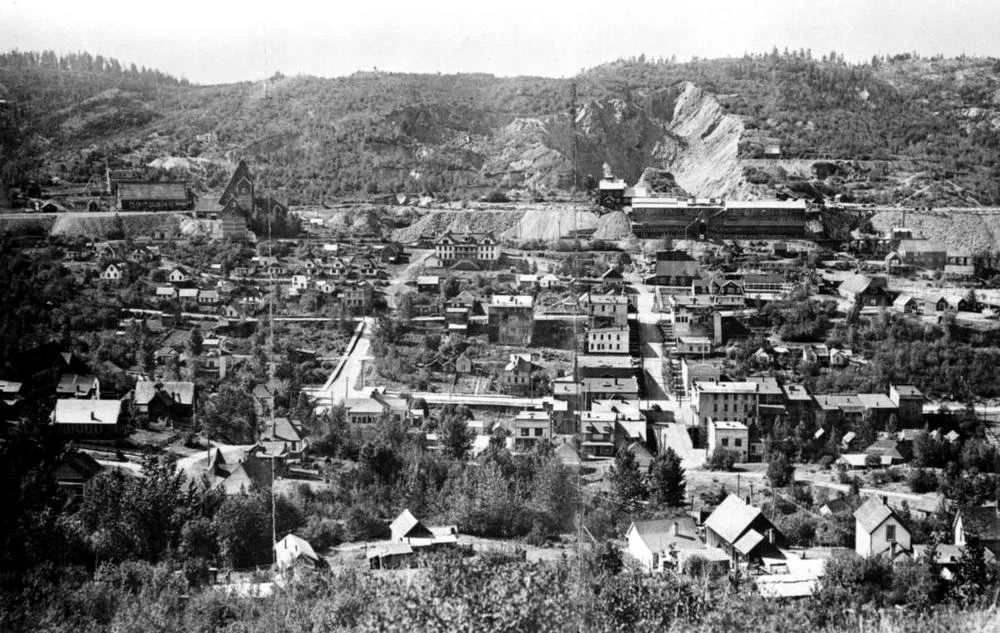

Phoenix, like Granby, Vancouver Island, passed from start to finish in a single generation. It’s hard to believe, looking at this photo, that such a sizable and established community could disappear from the map. —BC Archives

By then Gold Creeks and Ghost Towns was in its 24th printing in 32 years. At sales of 105,000 copies, Guide to Gold Panning was close behind. (In Canada, many consider 5000 copies to be a bestseller.)

Always ready to step up to the plate, Barlee set out to restore the ghost town of Sandon to its former glory as the mining capital of the Slocan by buying a block of surviving buildings. When they collapsed under heavy snow, he set out to rebuild them. This is one of the rare instances where his hopes didn’t pan out; the replicas were never completed. Earlier, as a cabinet minister, he’d succeeded in having Hedley's Nickel Plate and Mascot mines preserved as heritage sites by the province.

All of his experience had made him a champion of British Columbia's cultural heritage which, he firmly believed, is the province's greatest tourism potential.

Dave Obee, who interviewed him for the Times-Colonist, concluded his interview by declaring Barlee's passion for history to be his greatest asset: “Barlee has a deep, deep love for his native province and that love of B.C. shines through in virtually everything he does.”

When Bill Barlee died in 2012, his lengthy obituary noted his “rich and varied career as a politician, historian, television host, author/publisher, museum collector/curator, entrepreneur, and high school teacher,” and that he had long promoted British Columbia history.

His major contributions to provincial history and heritage hadn’t gone unnoticed, Bill receiving the Queen's Golden Jubilee medal in 2002, and other awards from hotel and tourist associations. The Times-Colonist's Obee, who’d interviewed him 11 years before, remembered him as “one of the sharpest, most inspiring, most likeable people I have known”.

Bill Barlee explaining something, with his usual enthusiasm, to television co-host Mike Roberts. —Earth’s Options Cremation & Burial Services

In Obee's view, British Columbia needs more politicians like Barlee, his passing that of “one of the greatest champions this province has ever seen”.

Randy Manuel, illustrator and former director of the Penticton Museum, considered Bill Barlee to be “a nugget, pure gold, remarkable in more ways than can be described.”

The Vancouver Sun's Vaughan Palmer concurred: “If any recent B.C. politician deserves a historical plaque, it would be him. Given how he knew, loved and chronicled so many places in the province, the hard part would be deciding where to put it.”

Also of the Sun, Stephen Hume, remembered him for having “lit a fire” under his students when teaching them about British Columbia history. Hume knew this for fact, having been a Grade 7 student of his: “Bill Barlee was a larger-than-life British Columbia character to whom the province owes far more than most of us will ever imagine.” Hume hopes that Barlee will be immortalized by a memorial that is worthy of his contributions to British Columbians' collective self-esteem.