The Real Man Behind Jack London’s Legendary ‘Sea Wolf’

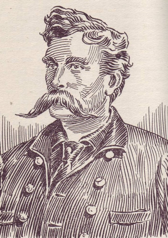

Capt. Alex McLean and his famous handlebar moustache was a living legend without any need of Jack London’s fictional ‘Sea-Wolf’ character. —Author’s collection

I have no idea what young boys read today.

Assuming, of course, that they read at all and it isn’t just computer games and watching videos and playing with their phones. (Mind you, they still play cowboys and Indians/cops and robbers, except that they call it paint ball.)

It’s nothing, I’m sure, like when I was young. Mind you, that was a few years ago. Back then (I’m speaking for myself) reading was it. Without the need of any encouragement from my parents or teachers my head was always buried in a book, and I don’t mean comic books.

My favourites were Mark Twain (in particular Tom Sawyer which I’ve read a half-dozen times) and Robert Louis Stevenson. There had to have been others besides The Hardy Boys; I remember reading stories about Canadian explorers, even enjoying my father’s monthly issue of Mechanix Illustrated.

I do recall Jack London’s White Fang but not The Sea-Wolf. That one didn’t come until many, many years later when, well into B.C. history, I learned that London had based this infamous character on a real-life Victoria-based mariner, Capt. Alex McLean.

McLean never forgave him, by the way.

The irony is that McLean was a living, breathing legend in his own time whereas Wolf Larsen, the Sea-Wolf, was the product of London’s vivid imagination and gifted pen. Hollywood even made a movie of the book in 1941, starring Edward G. Robinson and John Garfield.

Alex McLean, the real ‘Sea-Wolf,’ for those who believed him to be London’s role model, was long gone by then. But if London’s fictional character is still with us in literature, Alex McLean still resonates with those who know their B.C. maritime history and who enjoy a rollicking good sea story.

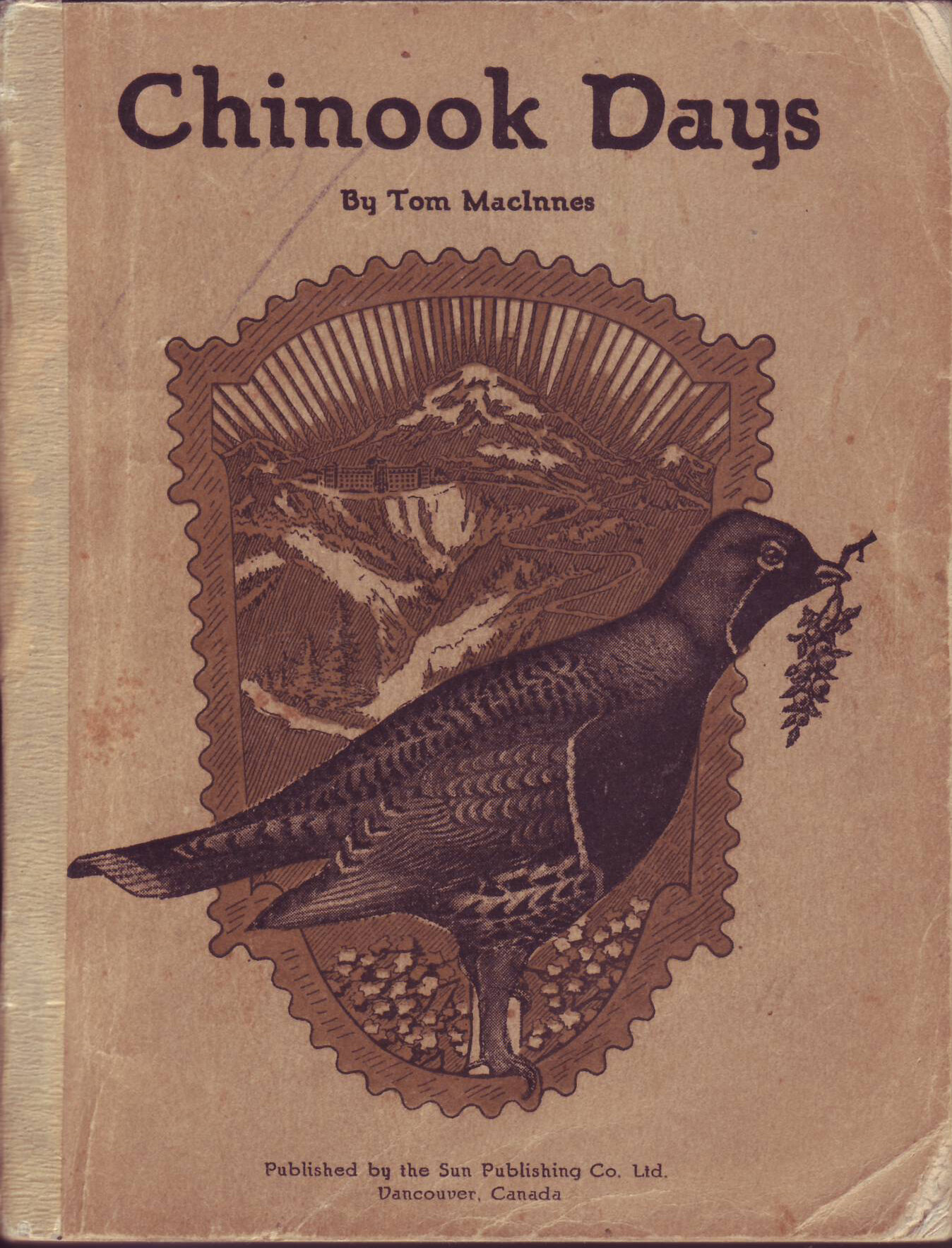

Thanks to Tom MacInnes, a friend of McLean’s of 30 years’ standing, today’s Chronicle is from a totally different slant than anything you may have read elsewhere. As a bonus, it’s from MacInnes’s 1926 book, Chinook Days which, long out of print, would otherwise cost you up to $100 for an original copy.

Because of its somewhat battered condition I paid 35 cents for my copy of Tom MacInnes’s Chinook Days at a garage sale. Check out prices on the internet.

* * * * *

Let me introduce you to Capt. Alex McLean:

Of all the rollicking, riproaring mariners to set course in British Columbia waters in days gone by, he’s without equal. The ‘Sea Wolf,’ they called him, from San Francisco to Sitka—and, without his consent, in Jack London’s novel of the same name.

But for his famous moustache—so long he could join it at the back of his neck—McLean’s stature and appearance gave no evidence of his flamboyant career. A friend remembered him as “a mild-mannered man, trim of dress—he affected Prince Albert coats and clerical collars—who would have been mistaken for a clergyman if he shaved off the long handlebar moustache”.

The 28-year-old Cape Breton Highlander of the steel blue eyes arrived on the Pacific coast in 1879 after nine years’ fishing for mackerel in the Atlantic. For a time he served as chief officer aboard the Sir James Douglas when the government cutter assisted in laying the first underwater cable between Point Grey and Vancouver Island, then he tried mining in Alaska.

Brother Dan joined him in 1883 to go sealing out of San Francisco. Alex gained his first notoriety when he was accused of smuggling; he insisted that his frequent calls at an isolated bay north of San Francisco were because of stress of weather and blamed the rumours on the jealousy of American sealers.

Schooners of the famous sealing fleet tied up in Victoria Harbour. —https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/fisherman/items/1.0013304

When pelagic sealing, mostly in the Bering Sea, became an international industry many of the hardy little schooners sailed out of Victoria. It soon became a battle of wits between the sealers and Russian and American coast guards’ ‘revenue cutters’, whose governments had set strict territorial limits on the annual hunt. Overnight, Canadian sealing masters risked seizure, imprisonment and, in the case of Russia, considerably more to hunt without restrictions.

Breathless newspaper headlines trumpeted one of the Sea Wolf’s several escapes in the northern seas:

“Out of Russia’s clutches; Capt. Alex McLean and the crew of the Hamilton Lewis are free; they will be in San Francisco next week; a lucky escape!

“Capt. Alex. McLean and [his] crew...who were seized by the Russian man-of-war Aleut off Copper Island, and subsequently taken to several Russian ports before coming before a tribunal for sentence, will stand on American soil within a week... With his proverbial luck, he has this time eluded the clutches of the Russian bear, and has almost miraculously escaped a Siberian convict prison, with all its suffering and agony.

“The bare details of the manner in which he and his crew were handled by the authorities...gave no positive clue as to the manner in which he has got out of his latest tight fix, but there is little doubt, as everyone who knows him will allow, that he has accomplished the feat by cool-headed pluck, and a determination to get back home in spite of everything.”

This latest adventure occurred well within the Russian patrol zone.

Alex, commanding the Lewis, was ashore, Dan standing by in his own schooner, the Kate and Anna, when the cutter Aleut crept out of the fog. Dan immediately hoisted sail, the Aleut steaming in pursuit after tearing away Alex’s top-hamper with a well-aimed shot. When Dan opened the gap between them, the exasperated gunboat turned back to Alex, who unsuccessfully attempted to foul its propeller with a length of chain.

It was four bitter months before the sealers were released into American custody.

At that, McLean had no complaint, the Colonist noting: “However heavy [an American] sentence may be made in order to appease Slavonic wrath, he will still have cause to be thankful for his escape from something a great deal worse.”

When next he drew public attention it was as an expert witness before the Behring [Sic] Sea Commission which was investigating sealers’ claims for reparations for ships and skins that had been seized. He had to endure a rigorous personal examination of his skirmishes with the authorities, on the Atlantic and Pacific, and admit to being jailed in Halifax (for six hours) for a ‘row,’ being arrested in ‘Frisco for the same reason, and being detained by the Russians for poaching.

The commission accepted his claim that Copper Island was the only complaint made of his having “violated the laws of any country”. Up to a point, McLean was telling the truth. But, years later, he’d honour to the hilt the sobriquet Sea Wolf given him by a rising adventure writer named Jack London.

Further exploits found McLean treasure hunting and putting down a mutiny in the South Pacific, answering charges of smuggling arms and, yet again, raiding northern rookeries. (His raid on a French pearl fishery likely would have gone unknown but for this week’s guest writer, Tom MacInnes.) Upon his death by misadventure, West Coast newspaper headlines proclaimed the end of an era: “Sea Wolf McLean makes last port.”

* * * * *

Over to Tom MacInnes:

Entitled A Night With the Sea Wolf (no hyphen) his story begins on a grim note written in newspaper-style:

Saturday, the 5th September, 1914. In the case of Captain Alexander McLean, a coroner’s jury at the port of Vancouver found that he had come to his death by accidental drowning in three feet of water.

A shallow reach of False Creek, as it then was, ran north between the railway tracks of the Great northern and the foot of Union Street, and there Captain McLean had anchored his little steam tug, the Favourite. To reach it one had to cross two other small boats, and it was supposed that he slipped and fell between them, striking his head on the gunwale of one and drowning while dazed and trapped between the two.

He had last been seen alive a week before.

Evidence was given at the inquest showing that he had been quite sober at the time. This was considered important, as the good townspeople in the kindly way which is second nature to them might have assumed that he had been drinking somewhat to excess when he met his mishap.

Sunday, the 5th September, 1914. The world was in the first uproar of the First World War. And so it is scarce to be wondered at that the passing at Vancouver of as picturesque a picaroon and master of little ships with sails as ever figured in a story book was barely noticed in the local press.

When the news reached me through an old acquaintance, I thought what a shabby trick of fate that so excellent a sailorman should meet with so paltry a death in a puddle of False Creek; a sailorman who had such an acquaintance with the wildest winds and most swinging great waves and shark-infested depths of the Pacific. A sailorman who successfully raided the Russian and American seal rookeries in Bering Sea, and almost as successfully robbed the French pearl fisheries of the Polynesian Islands to the south.

Just at a time when the Empire might have made the best of his skill and courage at sea he went away to regions beyond all seas. But thus, it seems, interesting characters sometimes play on a stage of their own contriving; in dull circumstances they can weave big events or devastating wars. Then unfitly they may end. So with the Sea Wolf.

I associate him three times with September; in 1914, in 1907 and in 1896. In September of 1896 and of 1907, I had to do with him pleasantly. Nothing with a smell of danger on either occasions; nothing even of the dramatic.

But sometimes hours of no special moment lie happily in memory; when we gladly forget times of risk and clashing events.

The September of 1907 was when the mob in Vancouver was stirred up to attack and ransack Chinese and Japanese quarters in Vancouver, egged on in the background by certain parties then making headquarters in San Francisco.

I wanted to know about some things in Vancouver, Seattle and San Francisco at the time, and the Sea Wolf was helpful to me. [What a shame MacInnes isn’t more forthcoming here.—TW] But the September I prefer to remember was in 1896 in Victoria.

One evening George and I went to the Garrick Head for a cocktail before dinner. It was a whiling hour, and between drinks the bartender told me that there was a man sitting alone at table near the window who wanted to speak to me.

I sent word for him to join us, and he came up. He was slim, trim, medium height, with very broad shoulders, blue eyes and an unusually large reddish brown moustache. He was of the handsome Highland type found among Nova Scotia seamen. I mind he wore grey trousers and a heavy, dark pea-jacket with brass buttons and cap to match.

He had been told by the bartender that I was one of the secretaries just appointed to the Bering Sea Claims Commission, which was about to open its sessions in Victoria to assess damages to be paid by the United States to Canada and Russia for illegal seizure of sealing schooners.

Garrick’s Head Pub, where McLean joined MacInnes for drinks, has been in business since 1867! --Foursquare

Captain McLean was an important witness for some of the claimants and he wanted to ask me how long a time I thought would be taken in preliminaries before he could give his evidence and get away.

He was negotiating even then for the purchase of the Carmencita, a schooner lying at anchor up the Gorge, sister to the Casco, lying alongside. It was in the Casco that Robert Louis Stevenson first sailed to the South Seas.

Subsequently McLean found it expedient to forge some credentials for the Carmencita, getting Mexican ship’s papers after being outlawed by United States coastal authorities. And it was on the Carmencita that McLean limped back into Victoria with the biggest cargo of sealskins ever taken there, after having been chased by Russian and American revenue cutters.

It was while McLean was raiding Robbin’s Island, in the North Pacific, that he had a running fight with an American revenue cutter, in which some of his men were killed. But with his skilled sailing and his fearlessness in chartless and rock-concealing waters and his elusiveness in friendly fogs, he always escaped capture.

McLean was a Canadian, born in Nova Scotia, but he had taken out papers as an American citizen. After his fighting encounters with the American revenue cutters he kept clear of American territory, except when on a raid.

Captain McLean asked us to have dinner with him. But George had a pressing affair that night and left, promising if possible, to look us up later at the Poodle Dog [Restaurant]. So McLean and I went there alone.

The Poodle Dog of that time, of course, is no more. It could not be; it belonged to a politer age, and one vastly more at ease with itself. Wine was cheap; love was free. Louis Marboeuf was of the old school, in which cooking was reckoned with the fine arts and dishes were prepared with the same care one gives to the structure of a sonnet.

The traditions of the place had not yet vanished in the gobble-and-get-out atmosphere of the cafeteria and good eats and white lunch hustleries of today.

They had a ravishing way of coking mussels, which were then in season And we were told that two fine blue grouse had just been received. There was no law against serving them. Then the substantial part of the meal having been ordered, with proper accompaniments, I looked around to see who else might be there.

And in one dim corner of that dim kafay I saw Vanilla. Her glance and smile were enough to light it up for me; I had a very friendly feeling for her as a right good chum, and no more. I had known her elsewhere as one of the quality; but she was the living quietly and in reduced circumstances at Victoria. I had been of some service to her in voiding certain deeds and saving a little property.

But her troubles had only left her sweeter than in her earlier years; as one may find a ripe hot berry in July sweeter than the tart impudence of the berries in early June.

I introduced the captain and the three of us dined together.

McLean was by no means the aggressive ruffian pictured by Jack London some years later in his novel, “The Sea Wolf.” Incidentally, in 1907, he complained bitterly to me about the way Jack London had maligned him. He expressed a hot desire to be in a position some day to shanghai him; and having him at sea put his through is paces in a way that he had never treated any man.

I argued that in Jack London’s nature there was evidently a perverse feminine streak, which made him fall to thoughts of cave conduct and stone-age standards, with a throwback to the delight of being mauled by gorilla lovers; a streak such as puts a certain psychopathic type of women in an ecstasy at bull-fights when they see blood flowing from men and beasts. [No comment!—TW]

Apart from that, and whether it were true or not, I suggested that London might have taken all the proven valour and skill of the McLean and blended it with what he knew of Bloody Fritz Hansen, the German captain, and Sapinza, the half Chinese half Filipino smuggler, once known on the American stretch of the Pacific as the King of the Opium Ring.

I said it was London’s right as a writer to try and make a new character out of them all, however beastly and unlikely a mix he made of it.

But at that McLean only scowled. He did not quite understand me; and of course I knew well enough that he was high above any fictitious character drawn by Jack London.

I knew him for a fair-going man with his men Yet once, on being asked how he controlled his crew at sea, when things went wrong in whatever odd business he had in hand, he answered: “Mac, I always carry enough handcuffs on my ship for the whole crew; and I have never sailed with a crew that I could not put the handcuffs on!”

But in the Poodle Dog that night this manner was gentle, and his words carefully chosen. He was evidently much impressed by Vanilla. It was only after the wine, however, that his tongue was loosened to tell me of some of his experiences. That sparkling pink wine was like tourmaline come alive for colour; it had a heavy, fruity flavour. Partridge Eye, I think we called it.

McLean took out of his pocket a small chamois bag; like a miner’s poke for gold-dust, but shorter. He rolled out on the tablecloth eleven pearls, and they glimmered in the rice which he had packed in the bag with them for some reason. I have heard that pearls keep well alive, and even grow larger when packed in with good rice.

Most of the pearls were round and creamy, and very sizable for rings. Two were like clouds of indigo touched with the moon as you turned them. And one was a large, oval, salmon-pink pearl. Vanilla was greatly taken with that one. Naturally, she asked him how he had come by them.

He answered that he had gotten them honestly and openly as a poacher in the South Seas.

His story was that a friend who was indefinitely confined at San Quentin had secretly passed out certain information to him in gratitude for a favour formerly rendered; and that having faith in what he was told him, he outfitted a schooner and sailed southwest across the Pacific for a little island among those owned by the French. At this island there was a season of pearling once in every ten years. It was the ninth year when he sailed; and the oysters were like to be in profitable condition. The trick was to get there and get away without being noticed by any prowling French gunboat.

One morning they sighted an island sure enough, as indicated on the plan which he had received. McLean had men with him who knew just what to do, and was enough equipped for quick work. So they went at it in the hot sun, and brought the oysters up against time.

Pearl diving hasn’t changed all that much since McLean’s raid on the French pearl grounds. —https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pearl_hunting

But about 4 o’clock on the afternoon of the third day a trail of smoke was noticed on the horizon. It was approaching the island. With all possible speed the mass of opened and empty shells and bottom debris on deck was put overboard together with pearling dredges and prongs, and every trace of what they had been so busy at was removed.

They had been lucky; there were many fine pearls, These they imbedded and covered in the pitch of the ship’s seams, By the time the French gunboat sent officers aboard to investigate, they found only an innocent little trading schooner, preparing to send some men ashore for a supply of coconuts, and intending to catch some fresh fish along the reefs.

But French authorities are very stubborn when they get a notion in their heads. Orders were given for the schooner to cast off and follow the gunboat to a French police and penal station on a distant island, where further consideration would be given to the affair.

There was no help for it; a shot or two from the guns, and in those remote waters the incident would be closed.

The Sea Wolf had to navigate under orders from two men left on board from the gunboat. This gunboat was old even then, and slow. It was destroyed by the Germans when they bombarded Papeete in the first year of the Great War. On the second evening after the capture it stopped for the night at an island, and entered through into the lagoon, followed by the schooner. The topic night was soon over them breathless, ominous, without a star.

Evidently a storm was brewing, but all was safe within the shelter of the lagoon. There was a cable between the schooner and the gunboat, but only two French sailors were left in charge. There was a small native settlement on the island, and some of the officers and men of the gunboat went ashore to enjoy themselves.

The storm came down very suddenly and heavily. Under direction of the Sea Wolf the two sailors left in charge were overcome without any outcry. The cable was slipped; the crew manned two boats and drew ahead, and presently, by grace of their oars and the rising wind, the schooner glided to the mouth of the lagoon and was guided through.

It was blowing great guns outside.

But that was all to the taste of McLean. His crew clambered aboard from the small boats; sails were hoist; they were away before the men of the gunboat realized what had happened. Out through the black raging sea they went, and McLean did not care where so long as he was heading for the open.

The thrill of that night made good for years of trouble. No gunboat followed, and eventually they reached the coast of Australia.

* * * * *

The next time I saw Vanilla she showed me the pink pearl. I asked her if she were going to have it set for a ring or a pendant. She said she was not going to tell me, but I might find out before the captain went away.

And so it was that when I said good-bye to the Sea Wolf he was rather self-consciously but proudly wearing the pink pearl in his tie, neatly set in five golden claws. For Vanilla was that kind of girl; she had delight in giving as well as receiving the unexpected gift. And her way was smooth, and her heart was sweet, even as her name.

* * * * *

There you have it, a brief outline of Capt. Alex McLean’s legendary career as a seal poacher and Tom MacInnes’s tale of the real Sea Wolf McLean. To my knowledge he’s the only one who tells the story of the raid on the pearl fishery in the South Seas.

If only he’d told us more about the exotic lady, Vanilla!

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.