The Real Story Behind the Cariboo’s Greatest Legend

Part 1

Anybody who’s ever read anything about the Cariboo gold rush has heard of John Angus Cameron.

Not by his formal name, maybe, but by the moniker by which he’s still remembered, ‘Cariboo’ Cameron.

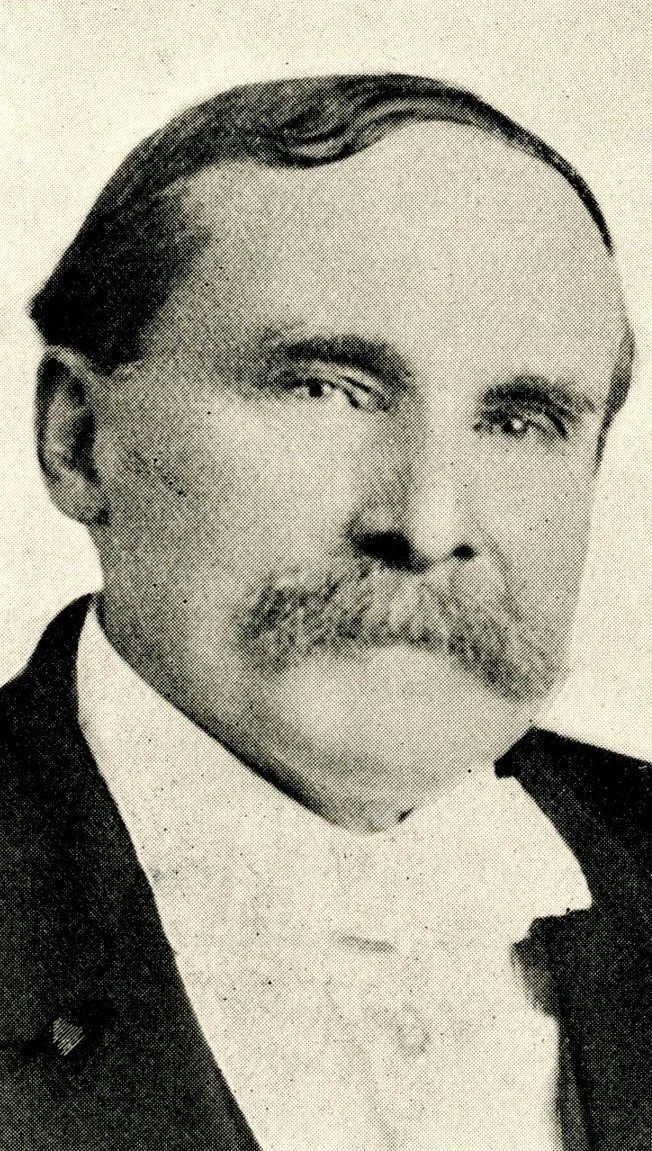

John A. ‘Cariboo’ Cameron. —BC Archives

If you do recognize his name, you probably have a vague recall of his claim to fame as the man who pickled his dead wife, then hauled her body 400 miles over snow and ice by toboggan to take her, first, to Victoria, then back home to Upper Canada.

Why would he do that? Because he’d promised her, as she was dying, he’d take her home to Ontario.

That pretty much sums up what the snapshot histories will tell you. But, of course, there’s so much more to the incredible Cameron saga. Herewith, the real and virtually unknown story of that epic winter journey from the mouth of the man who accompanied Cameron every agonizing foot of the way.

* * * * *

But first, I must introduce you to the principle characters. Cameron’s place in provincial history is, as noted, well established if only in thumbnail. But that of Robert Stevenson has gone, for the most part, overlooked. It’s thanks to Dr. W.W. Walkem, man of medicine, adventurer and, in retirement, author, that the fullest account of Cariboo Cameron’s claim to fame is recorded for posterity.

He did this by interviewing at length Robert Stevenson for his 1914 book, Stories of Early British Columbia, now considered to be one of B.C.’s rarest because the bulk of them were lost in a warehouse fire. An original copy can cost as much as $400CDN (plus shipping) online. (I found mine at a Nanaimo antique show years ago for considerably less.)

Now, let’s begin with some background to Cariboo Cameron’s claim to fame.

Almost unusual in the B.C. goldfields in that he was a Canadian, this descendant of Scottish United Empire Loyalists who’d moved north during the American war for independence, John Cameron was 25-years-old when he left the family farm near Glengarry, Ontario (Canada West as it was then) in 1852.

With his brother Alan, he joined in the California gold rush and, six years later, he and two brothers came north to seek their fortunes on the Fraser River. John did well enough, as much as $20,000 (then a king’s ransom), that he returned home and married Sophia Groves, his childhood sweetheart.

With Sophia and year-old daughter Alice, he again headed west, this time drawn by breathless reports of rich new strikes in the Cariboo.

Late in February 1862, after an arduous trip via the Isthmus of Panama and San Francisco, they arrived in Victoria where, weakened by their long journey, Alice died. The heart broken parents carried on to Antler, then to upper Williams Creek, where Cameron staked a claim.

Ned Stout’s discovery of gold below the canyon changed everything.

With five partners, including Sophia, Cameron moved downstream, choosing several claims half a mile below those of the Billy Barker company with his friend Robert Stevenson. After some argument, it was agreed to risk all on two adjoining claims, to be known as the Cameron, on the west side of the creek.

(All this according to Cameron biographers; as we’ll see, Robert Stevenson contradicts them on many salient points.)

* * * * *

The little-known Cariboo prospector and friend of Cariboo Cameron, Robert Stevenson. —Author’s Collection

Speaking of Robert Stevenson, what irony. Google him and you get...John A. Cariboo Cameron. If it weren’t for Dr. Walkem, poor Bob would be no more than a footnote in provincial history, with only his “fonds, 1863-1912,” buried in the BC Archives to mark his passing.

Walkem gives him no fewer than 20 pages in Stories of Early British Columbia, but I’m going to fast-forward to the epic tale of hauling wife Sophie Cameron’s body overland in mid-winter—as recounted by the under appreciated Robert Stevenson who risked all for his friendship to the Camerons. Other than for necessary edits, what follows is Robertson’s account as recorded from his interviews by Dr. Walkem.

* * * * *

Remember, this is Robert Stevenson speaking:

Victoria at that time was virtually a city of tents, for it was said that there were about 2,000 miners wintering there awaiting the opening of the mining season of 1862. Among the arrivals in Victoria that spring was John A. Cameron, afterwards known as Cariboo Cameron. He arrived on the second day of March 1862, and put up at the Royal Hotel. He had his wife and little daughter with him.

This little girl died on the fifth day after arrival. Her death was a great grief to her parents.

Stevenson described Victoria as a “city of tents” in 1862 with 2000 miners eagerly awaiting spring when they could proceed to the Cariboo diggings. —Author’s Collection

Cameron and I came from Glengarry, Eastern Canada, Canada, and in a short time after he arrived we became close and intimate friends. He told me that he had only $40 when he landed. As I had some money we agreed to go into partnership, and together we went to the Hudson's Bay Company store, where I introduced him. After a conversation of over an hour, the chief trader agreed to let him have $2,000 worth of goods, for which I went security.

Cameron subsequently paid his debt in full, when he and I brought his wife's body to Victoria in March, 1863.

I left Victoria on my way to Cariboo, on April 2nd, 1862, in company with three others, I arrived on Antler Creek on April 23rd, 1862.

The snow on the creek was seven feet deep, but not an icicle was to be seen. Forty-five of those who had started out with us could not keep up our pace, and fell behind and came in and twos and threes, for 10 days after. I went into the building I had purchased in the town of Antler, and engaged in a commission business, advancing money to packers, and getting 10 per cent for selling their goods. In less than four months, I cleared $11,000.

Cameron and his wife arrived on Antler Creek on July 25 following, but his goods were still at the Forks of Quesnelle. He was owing $1,400 freight money to Alan McDonald (afterwards Capt. Alan McDonald. I settled with McDonald and got him to deliver the goods in Richfield on Williams Creek. Cameron and McDonald had quarrelled on the way up from Yale, and were deadly enemies.

Among the goods which Cameron brought in was a large lot of candles, which were then selling at $5 per pound.

Candles at this time were very scarce, and I went to the several claims and sold them at $100 a box, 20 pounds to the box. They were poor, small American candles, and were badly broken up in the carriage on the animals’ backs, for a distance of 385 miles. Chips and all went at $100 per box.

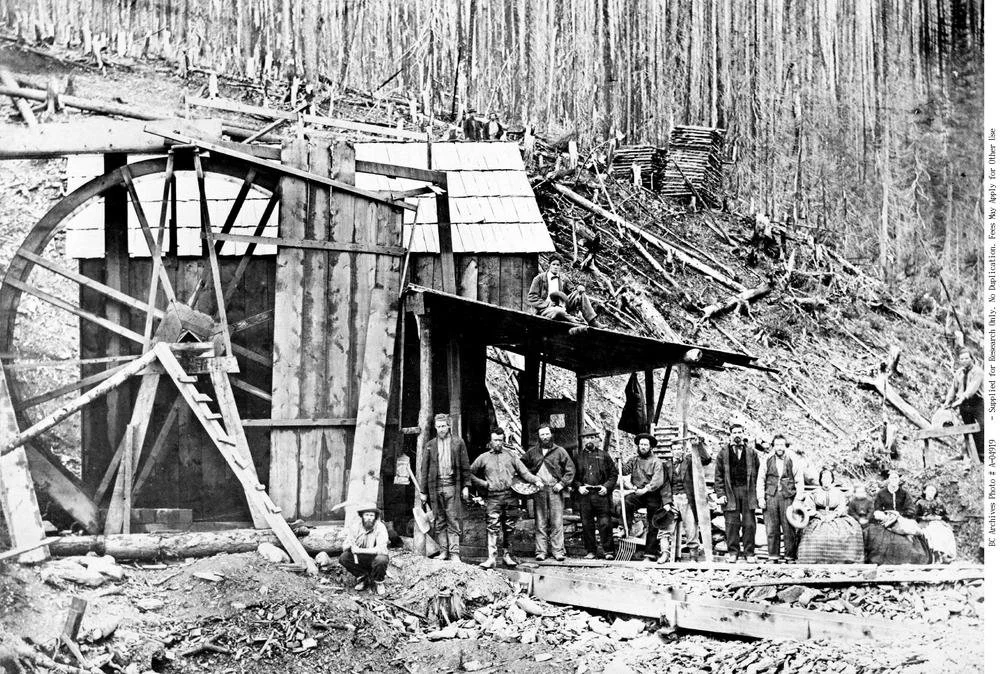

The strike at Stouts Gulch, shown here in 1868, inspired partners Cameron and Stevenson stake their claims farther down Williams Creek. —BC Archives

People had to take chances in buying them, and had to take them as they found them. Those were dear days in Cariboo. I will give you a few of the prices asked and paid: Nails, $5 per pound by the 100-pound keg; butter, $5.00 per box; bag of salt, (5 lbs.), $7.50; flour for noine days was $2 per pound; no one was allowed to buy more than two pounds at a time; potatoes $1.50 per pound in 100- lb. Sacks, $115.

About this date I sold my business on Antler Creek, and went to Williams Creek, just in the nick of time, to get into what was known as the Cameron claim.

Dr. Crane had told me of the ground being vacant, and wanted me to go in with him that night and stake it off. I told him I had a few friends I would like to take in with with us, so organized a company as follows: J. A. Cameron, Sophia Cameron, Robert Stevenson, Alan McDonald, Richard Rivers, Charles Glendenning and James Glendenning.

I had to wait a day and a half on Cameron to come with us to stake the claim. Cameron was nearly not coming that morning to stake the claim, as he had a prejudice against doing so on a Friday, as he thought it was unlucky.

When staking, Cameron and I disagreed, and then quarrelled over the location, and if he had followed my advice the claim, instead of paying, one million dollars, would have paid double that amount. He would insist on single claims on the left bank of the creek, and I wished to stake two claims abreast on the right bank.

If my plan had been followed, the Tinker claim would not have been heard of, and Henry Beattie of Toronto might not have been a millionaire today, for the Tinker claim, in which he was interested, paid nearly as well as the Cameron, and put him right on his feet.

[Readers are going to see that Stevenson unabashedly claims credit for having made all the right moves and, ultimately, saving the lives of those attempting to take Sophia Cameron’s remains to the coast in wintertime. I leave it to readers to judge his immodesty and veracity. At the time of his interviews with Dr. Walkem, there were few left alive to contradict him!—TWP.]

For those fortunate to have good claims, and willing to do the excruciating work, the payoffs were handsome. These bottles are filled with gold nuggets. —BC Archives

After staking the claim, we sat down to name it. This was on Aug. 22, 1862.

Dr. Crane proposed that it should be called the Stevenson claim because I got up the company. I objected to this and asked the privilege of calling it the Cameron claim, and so it was called. Crane, at this time, had a full interest in the claim, but lost it through getting into a row in a saloon in Richfield, where he drew a pistol and fired at some person. Though no one was hurt, he was given 30 days in jail by Judge Elwyn, in addition to a heavy fine. As we did not wish this kind of a man in the same company with us, we forfeited his interest.

The third shaft was sunk by Charles and James Glendenning, R. Rivers and myself, but we lost it at 22 feet, and the work was stopped. The Glendennings went to Victoria, refusing to work on the claim, or to leave any money to aid in sinking a shaft. This was on September 26. At this time there was a heavy snow fall of snow, and the ground was well covered with it.

Two weeks prior to this, Mrs. Cameron was taken ill with mountain fever, as they first called it, but it was typhoid.

She was a tall, beautiful woman and 28 years of age. I helped to nurse her, and used to tramp through the heavy brush and snow at midnight to take my turn and see that she got her medicine regularly, and that other directions of the doctor were carried out. She was attended to by Dr. Wilkinson.

Mrs. Cameron died at 3:00 a.m. on Oct. 23, 1862. Richfield was the name of the mining town where she passed away. Cameron and I were the only persons present at the time. I happened to be there, as it was the period of my morning watch. Poor Cameron! His wife's death was a great blow to him. He certainly had his periods of grief. It will be recollected he lost his only child five days after his arrival in the province.

The morning Mrs. Cameron died was intensely cold, the thermometer standing at 30° [F] below zero, and the wind blowing at the rate of 60 miles an hour. As there were no undertakers in Cariboo in those days, I went away and engaged Griffin to make a coffin, and Henry Lightfoot of Vankleek Hill made the case.

You must understand that at that time there were very few women in Cariboo, but her remains were laid in the coffin by Griffin, Loring and myself, who came from the same place in Eastern Canada. Mr. Cameron intended taking the body back to the place of her childhood, so after being enclosed in the tin and wooden case it was placed in a cabin at the back of Richfield to await removal to Victoria.

Out of 8,000 miners who worked in Caribou during the mining season in 1862 there were only 90 left to attend the funeral in the winter.

Two days after the funeral, Dick Rivers and I started work again upon another shaft on the Cameron claim. I might say two shafts, as Rivers and I, like Cameron and I, in the location of the claim, disagreed. Rivers and I could not agree on the exact spot to sink. Like Cameron, he wished to keep too much to the left bank, so each of us started on our own chosen spots, and worked until noon, when Rivers gave in and came and joined me.

These Cariboo miners are “cleaning bedrock.” The Cameron claim was a shaft, dug straight down through the earth and stone. —BC Archives

We had the shaft down 14 feet before Cameron came down to see how matters were progressing, when he had once said that I was right in my selection of the spot to sink. It was afterwards proved that a shaft on River’s selection would have missed the rich pay. At 14 feet we met with a lot of water, and had to engage William Halpenny to assist us. This William Halpenny was afterwards Government guide for the placing of immigrants on suitable locations...

Well, as I was saying, we employed Halpenny and three others to help us. On Dec. 22 we struck it very rich at 22 feet.

Dick Rivers was in the shaft at the time, and Halpenny and I were at the windlass. I may tell you that it was 30 below zero at the time. Cameron had just come down from Richfield to see how we were getting on, when Rivers called up from the bottom of the shaft: “Cameron or Stevenson—come down here at once—the place is yellow with gold! Look here, boys!” at the same time holding up a flat rock the size of a dinner pail.

I laid down flat on the platform and peered into the shaft. I could see the gold standing out on the rock as he held it. “Put it in the bucket and send it up,” I said, and in a short time it was on the surface. I got $16 out of this piece of rock.

Then Cameron started down the shaft, and while he was there I took my pick and went through some of the frozen stuff that had been sent up all morning, and got $16 before he came up again. Out of three 12-gallon kegs of gravel I obtained $155.

Of course, this turned out to be one of the best claims of the Cariboo.

Sinking, we found bedrock at 38 feet. It was good all the way down from 22 [feet] to there, but the richest was at 22 feet. Strange to say, the coarse gold was at 22 feet. We now knew that we had what we had, but we agreed to keep it quiet for a short time.

Cameron was anxious to have his wife's body removed to Victoria and there embalmed, and had offered $12 per day, and $2,000 to any hearty man who would make the round trip to Victoria with his wife's body, and I was to stay in Cariboo and work the claim. On the evening before starting, he was told that the last man whom he had engaged had backed out. The smallpox at this time was raging all the way down to Victoria, and men were timid about catching it.

(To be continued)