The Real Story Behind the Cariboo’s Greatest Legend

Conclusion

As we saw in last week’s Chronicles, John A. ‘Cariboo’ Cameron pickled his dead wife then then set out to haul her body 400 miles over the snow and ice by sled to take her, first to Victoria, then back home to Upper Canada.

John A. ‘Cariboo’ Cameron. —Wikipedia

He’d promised her, as she lay dying, he’d take her home to Glengarry, Ontario. Determined to do so despite knowing that they’d be heading into an outbreak of smallpox, Cameron hired two dozen unemployed miners for $12 per day and the promise of $2000 bonus upon arrival in Victoria.

But, if it weren’t for his faithful friend and mining partner Robert Stevenson, and Dr. W.W. Walkem, that’s as much as we’d know about this incredible epic of devotion and physical stamina. It was Walkem who, years later, interviewed Stevenson at length for his book, Stories of British Columbia.

Now extremely rare, it’s not only out of print but most copies were lost in a warehouse fire. Here then, the conclusion to Stevenson’s account of that Cariboo saga, and to Cameron’s ultimately said finish.

What follows is in Stevenson’s own words:

* * * * *

It was the genuine old smallpox, which left its marks behind it, and was somewhat fatal, too, to those who caught it. Cameron was very much broken up by this disappointment, and seeing this, I said I would go with him, but he said, “No, you have never had the smallpox, and I would feel very badly if you caught it.”

I told him I was willing to take the chance, but he objected on the ground that I was required to run the claim. I told him we should appoint Evan Jones to run the claim until we returned, and as for the smallpox, I wasn't afraid of it. ‘Well,” said Cameron, “if you will go, I would rather have you than any man in Cariboo. " I said, “I'll go, but I will pay my own expenses."

Our narrator, Robert Stevenson. —Author’s Collection

On the last day of January, 1863, we started up the mountain opposite Richfield, on the way to Victoria. There were 22 of us, and we started out shortly after daylight. There were six or seven feet of snow, and two feet on the top of that, and newly fallen, so it was very soft. We were all on snowshoes. The box containing Mrs. Cameron's body was placed in the toboggan, to which it was lashed. The toboggan was 14 inches in width, and on top of the box, were 50 pounds of gold dust, our blankets and a considerable amount of grub.

There wasn't any sign of any trail, not even the mark of a dog's foot. I was appointed leader and guide. There was a long rope attached to the toboggan, and as leader I took the end of the rope over my shoulder, and started off, every one of the remaining men taking a hold also. As the load was top-heavy, it was constantly turning over.

The climb up the mountain was so difficult that at 12:00 noon, we had only made three and a half miles.

It was very evident that by going that way we would not reach Tim Maloney's that night. As I was guide, I turned off sharply to the left for Grouse Creek, through the thick green timber. They were all badly scared that I would miss it, but I didn't. Even after striking Grouse Creek it was hard to make some of them believe it was Grouse Creek. We followed up Grouse Creek and reached Maloney's some hours after dark.

Next morning, it was 35° [F] below zero, and the wind was blowing a gale, and the snow drifting most terribly, for at Tom Maloney's there was no timber. At this point, 14 men returned to Richfield, but eight kept on with us. Our party now consisted of Cameron, myself, Dr. Wilkinson, A. Rivers, Rosser Edwards, Evan Jones, French Joe and Big Indian Jim.

We went by way of Antler and Swift River. It was bitterly cold. We had no tent so we slept in the open, the spirit thermometer belonging to Cameron, hanging from a branch from a limb of a tree, registering 50° below zero. We traveled very slowly, the snow being dry and loose, and the toboggan being top-heavy, was constantly turning over and spilling everything.

Between Swift River and Snowshoe Creek, our “grub” gave out, leaving us without a bite to eat.

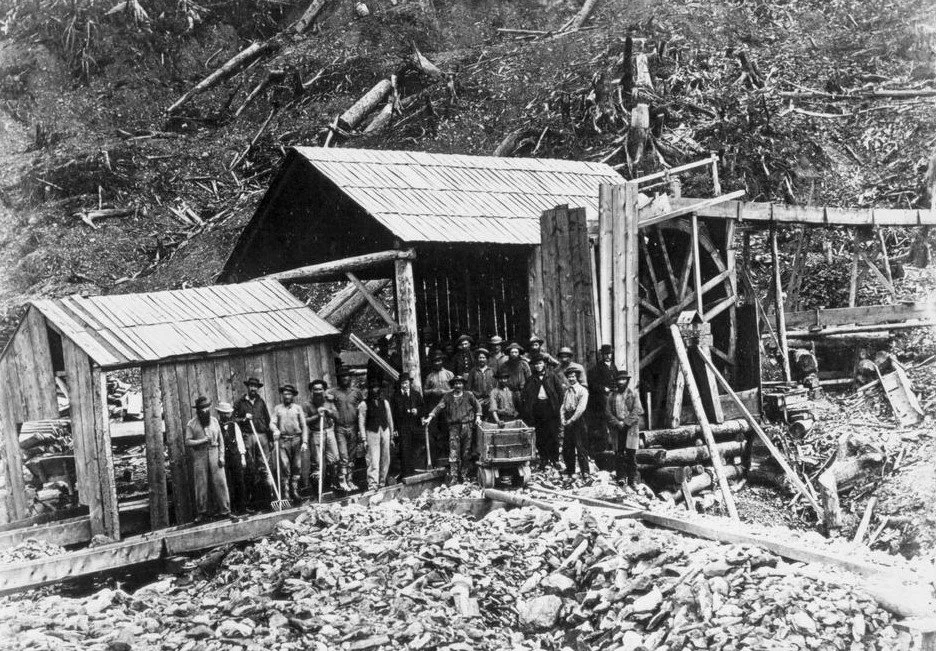

Williams Creek, 1865. In the summer, hot and dry. In the winter, bitterly cold with deep snow, as Stevenson, Cameron and their hired crew found to their great discomfort. Not one of the 19 men who were hired made it as far as Victoria to collect the $2000 bonus Cameron had offered them to take Sophia’s body there. —BC Archives

Another disaster was the loss of our rum, from the two- gallon jug. It was what was known as Hudson's Bay rum, and like all the liquors that company sold, of the best. This keg was carried on the toboggan with the grub and blankets, and once when the toboggan was upset the keg rolled down a steep short bluff, struck against the tree and knocked the bung out.

Before it could be salved, the spirit had all escaped from the keg. To add to our misfortunes we found that all our matches had been destroyed. It was well on in the afternoon, and the sun a little above the trees, when our unfortunate position was realized. We at once held council as to what we should do.

Our position was a desperate one.

We were in a thick spruce forest, without the first sign of a trail, and no food left to allow of our spending any time to gauge our position in the surrounding country. We were between Swift River and Snowshoe Creek, and the only chance to save our lives was to find Davis's Crossing on Keithly Creek, where a German kept a “road house” and a small store.

The question arose, “Who would go on and find Davis' Crossing?” The other seven said they were too tired, and were afraid they would be unable to find the crossing. Even French Joe and Indian Jim funked it, and refused to go; but they were all kind enough to suggest that I was the man to go, as they were sure I could find it.

Such disinterested willingness on their part to allow me the honour of piloting them out of their desperate position rather ruffled me, but when Cameron and Doctor Wilkinson came to me, and with almost imploring looks said, “Will you go?” I replied very briefly, “Yes, I will, and find it, too; don't be the least afraid. I'll not make the least mistake.”

“If you do,” said Dr. Wilkinson, we are all dead men; we are all depending on you.” “Remember this,” I said to Dr. Wilkinson, “after dark you will find it most difficult to follow my snowshoe tracks.”

Well, I started off and made straight for the crossing, not making the slightest deviation, and got there a few hours after dark. Loading myself with supplies of bread, meat and some matches, I started back to meet them. I found them coming on slowly, following my tracks. They were all glad to meet me, but told me that as they had no matches they had had a most difficult time following my snowshoe tracks.

Dr. Wilkinson and Cameron both said, “You have done well –God bless you—you have saved our lives.”

French Joe and Indian Jim were carrying the blankets, and the 50 pounds of gold. The body was on the toboggan some distance back in the forest, where we had been obliged to leave it. At daybreak next morning, we started back for the body, and returned with it to the crossing that night. Next day, we walked down the creek to its mouth, where there were a house and a small store. At this point Dr. Wilkinson, Richard Rivers, Rosser Edwards and Evan Jones turned back to William’s Creek.

Cameron, Joe, Indian Jim and myself continued on to the Forks of Quesnelle, where we arrived during the night. We sought the shelter of a hotel there, managed by Mrs. Lawless... She endeavored to induce me not to proceed to Victoria on account of the smallpox, but to return to William’s Creek. Of course, I couldn't do that.

Next morning, we went on as far as Beaver Lake, where French Joe and Indian Jim left us to return to William’s Creek.

This was on the 10th of February, 11 days since we had set out, and only covering 72 miles. At this time, the weather was intensely cold, the thermometer ranging between 40 and 50 below zero. I counted 90 snow graves of Indians who had died here from the smallpox. There was only one adult Indian of the Beaver Lodge tribe living. All the rest had succumbed to the dreaded fever.

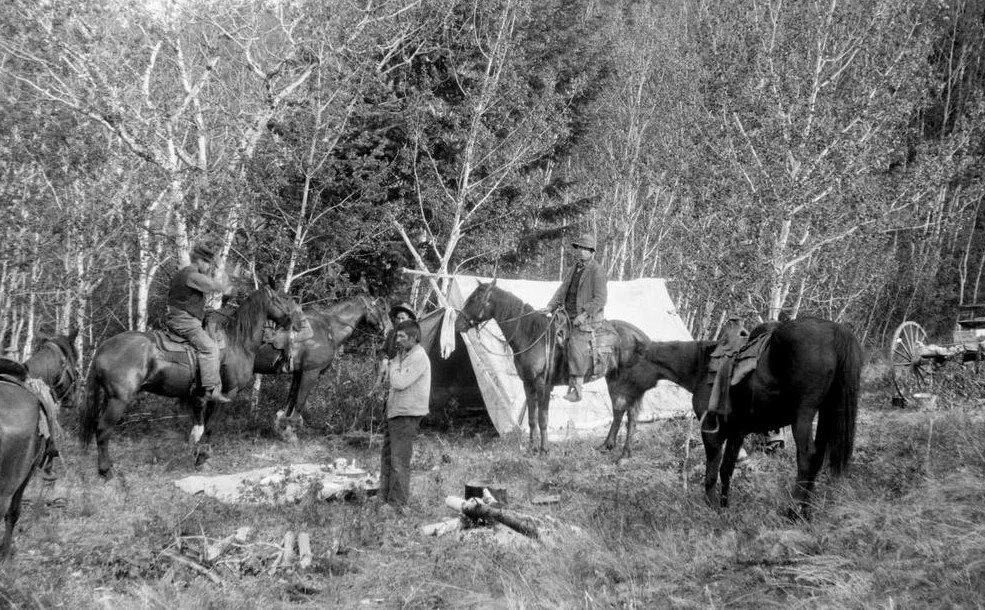

These Williams Creek miners were lucky—they had horses. For much of their journey, the Cameron party had to haul Sophia’s temporary casket—and 50 pounds of gold—themselves. —BC Archives

Here, Cameron bought a $300 horse and hitched it to the toboggan. After this, we marched along; I was in front, then the horse and toboggan and Cameron bringing up the rear. The snow was not so deep here as it was about William's Creek, being only two and a-half feet. At Deep Creek, Williams Lake and all through the valley of the Lake La Hache [sic], smallpox was epidemic.

At William’s Creek, I counted 120 Indian snow graves, and only three full-grown Indians left. When I use the term snow graves, I mean that the bodies were only covered with snow, awaiting the opening of spring and milder weather to dispose of them properly.

At old Mr. Wight’s in the Lake la Hache Valley [sic], there were two snow graves within six feet of his door. The old man was living alone. In one grave was an Indian who who had died of smallpox, and the other contained the body of a white man...

We passed on to Lillooet—smallpox everywhere. We crossed the Lillooet-Douglas Portage in deep snow. On the Pemberton Portage we met, for the first time, Jim Cumming, now living at the “150” [Mile House] on the Cariboo Road. The smallpox at Douglas was awful, white and Indians both being carried off.

We had purchased, at odd times, three horses in all, to help us transport our things over the nearly 400-mile journey from Cariboo. Two of these had died, and the third we had no further use for, as we were at the end of land transportation, and our journey from there on was by water. On our way to embark on the little steamer Henrietta, we had to pass over a road lined by two rows of tents on each side of the road. The flaps of these tents were raised sufficiently to let us see Indians lying thereunder in all stages of the disease.

Some of them were actually black with confluent smallpox, and the stench peculiar to the disease was simply awful…

(On March 6th, at New Westminster they boarded the steamer Enterprise, Capt. William Mouat commanding, for Victoria. Arriving the same day. Stevenson continues:)

The Quadra Street Cemetery, aka Quadra Street Burying Ground, aka Pioneer Square as it looks today. Many of its headstones were clustered along the back fence by a cost-cutting city works department years ago and their original placements are unknown. Fortunately for Sophie Cameron, her sealed casket was exhumed and shipped home to Glengarry, Ontario. —Author’s photo

The body of Mrs. Cameron, still in a frozen condition, was handed over to Mr. Lewis, the undertaker... By him the metal coffin was filled with alcohol, sealed up, and the following Sunday, March 8, the second funeral was held, and the body was buried in the Quadra Street cemetery. There were about 800 people at the funeral, and if due notice had been given there would have been four times that number, for it was the winter season and the city was full of miners.

We only stopped a few days in Victoria, when we again returned to Cariboo by way of Yale and Lillooet.

Our return was made as far as William’s Lake, this time on horseback. These horses cost us $350 each. We left the animals at the lake and proceeded on foot to Williams Creek by way of the Forks, Keithley Creek, Live Yankee’s on Bald Mountain, Antler Creek, Tom Maloney's, and arrived at our creek on April 4, making the trip in 66 days.

I may say that the trip down to Port Douglas was the most severe and trying I have ever experienced, [most of it] through the snow. During our absence, our new strike had caused great excitement and from that time on it was one continuous rush to the Cariboo.

* * * * *

The saga of Cariboo Cameron didn’t end with his reclaiming Sophia’s coffin to take her home to Ontario. In the spring of 1863, with her temporarily interred in Victoria, he returned his attention to mining by buying out two partners and acquiring two adjoining claims before heading back to Williams Creek.

There, all that summer, crews of miners hauled out the gold in buckets and a town named in his honour, Cameronton, sprang up on the neighbouring flats.

Wash-up day, June 15, 1867, yielded 485 ounces of gold. —BC Archives

John Cameron was rich beyond his fondest dreams, with gold and shares that, in today’s values, amounted to something in the order of $5 million. Only then, true to his promise to Sophia, did he escort her home for what he intended be her final burial.

He gave $100,000 to his five brothers, throwing in a farm each for the two who’d accompanied him to the Cariboo, established an educational fund at Queen’s University for younger Camerons, was generous with his friends, built a mansion, invested in a canal scheme and mining properties in eastern Canada, and remarried.

His fall from fortune and grace is almost as incredible as his rise to success.

Ugly rumours began to spread that he’d brought home a coffin filled with gold—that he’d sold Sophia to ‘an Indian chief’ to raise operating capital! A libellous account in an American newspaper of her escaping bondage and returning to Cornwall was the final straw. At great pain to himself and to his former in-laws, Cameron put the rumours to rest by having Sophia exhumed. Her features, preserved by the alcohol, were yet recognizable.

The Cameronton Cemetery as it was in 1946 when photographed by the famous B.C. land surveyor Frank Swannell. —BC Archives

After losing what remained of his fortune to bad investments, John Cameron returned to the Cariboo with his second wife in hopes of making another strike. Instead, he dropped dead of a massive stroke and was buried in Barkerville’s picturesque cemetery–the cemetery that he, John A. ‘Cariboo’ Cameron had laid out a quarter of a century before.