The Ship That Came Back From the Grave

Part 2

As we’ve seen, the aged and decrepit steamship Clara Nevada appeared to be doomed from the moment she cleared her Seattle dock in February 1898. But, somehow, bound for the Klondike gold rush with passengers and freight, she managed to make it to Skagway.

A Seattle newspaper termed her safe but eventful arrival as nothing less than a miracle.

The S.S. Clara Nevada was unfit to sail, but sail she did—into disaster—because of the frantic need for shipping during the Klondike gold rush. This hectic Seattle dock scene gives an idea of the excitement that prevailed at the time. —Seattle Public Library

It was on her return trip, this time with an estimated 40-60 (some say as many as 165) passengers and a crew of about40-40, that she struck uncharted Eldred Rock in Alaska’s infamous Lynn Canal and was lost with all on board.

Or, so it seemed at the time.

That almost all passengers and crew died in the wreck appears to be certain. But, did everyone perish? Not so, according to tantalizing evidence that has come to light over the past 125 years.

Capt. C.H. Lewis, to name one, appears not to have gone down with his ship but to have died years later in his hometown of old age!

How could that possibly be?

And what of the Clara Nevada’s reputedly rich cargo of gold, worth millions of dollars today?

Writing in Last Frontier Magazine, Steven Levi has pulled all stops on this maritime mystery by terming it nothing less than “one of the largest successful robberies...combined with the third largest mass murder in American history...surpassed only by the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995 and the 911 attack on the World Trade Center”.

I remind readers that we’re discussing a 125-year-old shipwreck!

All hyperbole aside, there’s no denying that the mystery of what really happened to the Clara Nevada is one of those stories that, as Alice of Wonderland fame would say, gets curiouser and curiouser....

So, let’s go back to the very beginning and a brief recap before we get down and dirty...

* * * * *

Long before she met with disaster in Lynn Canal, the Clara Nevada had carved a modest niche for herself in nautical history. The first iron-hulled steamship to be used in the service of the United States Coast Survey, she actually was a three-masted schooner equipped with a 125 hp steeple compound engine capable of driving her along at a top speed of eight knots—nine miles per hour.

Like a tugboat, she was meant to work, not race.

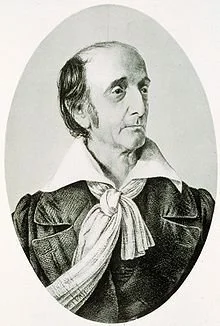

Ferdinand Rudolph Hassler. —Wikipedia

She was christened Hassler in honour of the Swiss-born surveyor

Ferdinand Rudolph Hassler (1770-1843). who’s considered to be the forefather of both the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (Weights and Measures). He also served as the first superintendent of the U.S. Survey of the Coast.

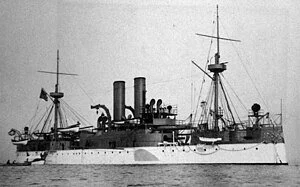

The U.S. Survey Ship Hassler which would be sold to private owners and renamed Clara Nevada. —Wikipedia

In 1871-72, the new Hassler began earning her keep by sailing on “the first important scientific expedition sent by the [U.S.] government for marine exploration”. This required that the New Jersey-built ship sail from Boston to San Francisco.

As this was pre-Panama Canal, it meant a lengthy voyage around Cape Horn, which allowed the scientists aboard to practise their scientific skills in the study of sea life and conditions, including a side-trip to inspect South American glaciers. (Many of the zoological specimens collected along the way are in possession of Harvard University.)

After almost a quarter century of hard sailing, the Hassler was deemed to be old and tired. Her stalwart steam plant still functioned efficiently and economically, but her innovative double-hull of iron was failing badly; not only beyond viable repair but, short of starting over again, beyond the technology of the day to extend its life.

The problem lay in her very innovation—she was the first iron-hulled ship built for the U.S. Coast Survey. This would prove to be her Achilles Heel.

American shipbuilders had been slow to embrace constructing ships of iron despite iron’s known advantages of lighter weight and greater strength than traditional wood. Even by 1871, when the Hassler was built, iron ship construction remained something of a novelty in the U.S. and it showed in the numerous changes and revisions that were made throughout the new ship’s completion. Some of these were to take advantage of newly developed technology,

Hassler was expected to be seaworthy, operate economically during lengthy voyages, have a modest draft for survey work, and be able to function with a crew of 37. All said and good, but the fact remained that, as of 1871, American iron ships were still in the experimental stage. So it would prove with the Hassler.

Although her builders, River Iron Works of Camden, New Jersey had extensive experience in steam propulsion and boilers, they were new to iron hull construction. Faced with making changes as they went along, changes that took more months to complete on a fixed budget of $62,000 (modest even then), there was little profit margin and, perhaps, little incentive other than to get the job over with.

All of these factors became apparent during the new ship’s maiden voyage when everything leaked—the hull, the decks, the engine fittings.

These were eventually sorted out. Somewhat ironically, her steeple compound steam engine, also experimental and cutting-edge technology, worked well for the life of the ship and surpassed all expectations for low fuel consumption.

But the inherent flaws in her iron double-hull were there to stay. Double-hulls, as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s website explains, “created a sealed space between the bilge (the lowest interior place inside the ship) and the outer hull. A series of watertight bulkheads further divided the space into a series of empty voids.

“In most ships, each void had access plates to allow for inspection and regular painting. On the Hassler, the double bottom occurred as a major design change during construction, and some of the spaces lacked any form of access. This included the voids underneath of the coal bunkers.

“Without regular inspections and painting, saltwater combined with heat from the boilers and the acid run-off from wet coal created serious corrosion problems that plagued the Hassler throughout her career.”

(As a longtime collector of coal mining memorabilia, I can personally attest to the chemical process that occurs from lengthy, direct contact between iron and coal—the latter’s sulphur content can literally eat iron alive.—TW)

In just 10 years, the Hassler’s double bottom beneath her boilers “had entirely corroded away”. Despite major repairs in 1884 which included pouring cement into the cracks and crevices, “mid-ship corrosion remained a problem,” and became particularly apparent during storms when the hull sometimes began to twist.

She was again repaired in 1892, but, just a year later, her captain reported her to be “on her last legs” and capable of only a few more years’ service “barring accident”. Storms that stressed her hull, and the possibility of striking bottom and rupturing were his major concerns; he recommended that her survey work be limited to “comparatively smooth water”.

Retired in 1895, Hassler was placed in reserve for two years until offered for public sale. Coincidentally, her disposal came at the frenzied start of the Klondike gold rush in the spring of 1897. As described in last week’s Chronicles, the resulting stampede was a human race to the northern diggings.

In one of the most iconic photos in history, men laden with supplies labour upward through Chilkoot Pass. Nothing seemed to daunt these gold seekers. —www.pinterest.com

Like lemmings, men and women literally stopped what they were doing to join in the mad scramble. The quickest way to get to the Klondike was by coastal steamship. But this obviously cost money, so all manner of vessels were pressed into service—from home-made rowboats to rafts.

No matter how crazy, no matter how dangerous it was, if it floated and it could be propelled, it was good enough!

The resulting sea-borne contingent was a recipe for disaster with unscrupulous shipowners defying every standard of safety and comfort in their rush to sell tickets on any type of vessel, many of which had long outlived their seaworthiness. In 1898 alone, 16 ships were lost while transiting the Inside Passage.

One of these tired hulks was the survey ship Hassler.

Bought by the McGuire Brothers’ Pacific & Alaska Transportation Co. of Portland, Ore., for $15,700 and renamed Clara Nevada after a popular actress of the day, she took aboard an estimated 160-odd passengers. Then, with 40-odd officers and crew described as drunks and incompetents, she cleared Seattle for Skagway.

To quote passenger Charles Jones: “I was afraid that [she] would be wrecked from the time she left Seattle until Skagway was reached. We smashed into the U.S. Revenue cutter Grant when we were backing out from the Yesler dock [in Seattle]; we rammed into almost every wharf at which we tried to land; we blew out three flues; we foundered around in rough water until all the passengers were scared almost to death.

“We witnessed intoxication among the officers, and heard them cursing each other until it was sickening...”

Also, in describing that incredible voyage last week, I quoted from the Seattle Daily Times which editorialized: “That she ever reached her destination is one of those modern miracles which God sometimes works in spite of man's failings, avarice, incompetence and greed.

“The whole story of that north-bound trip excels anything that has ever been told of a voyage on this Pacific Coast. It is a story that should bring the blush of shame upon the cheeks of the owners of that vessel, and that should bring the righteous indignation of an outraged public upon the heads of the culpable inspectors at this port.”

For all that, the Clara Nevada had made it to Skagway by the skin of her teeth. It was on her return voyage from Dyea, Alaska to Seattle with a small company of passengers (supposedly successful Argonauts who’d struck pay dirt) that she struck uncharted Eldred Rock in Lynn Canal, late on Feb. 5, 1898, with the loss of all on board.

Not only has the initial belief that there were no survivors been questioned in later years, so has her striking Eldred Rock, the teensy-weensy tip of a 100-foot-tall underwater mountain, come under scrutiny. The fjord-like waters of Lynn Canal are among the deepest in North America, but the tip of Eldred Rock is only four fathoms—24 feet—below the surface.

By what freak of fate—or evil human design—did she manage to rip out her rusty bottom on this pinprick hazard? Was Eldred Rock shallow enough to allow some, say a chosen few, to escape, even in stormy seas?Seeking it out at night, in a storm, would have been quite a navigational feat, to say the least.

Despite the inclement weather, an unnamed witness who was standing on a wharf in nearby Seward City (on Resurrection Bay on Alaska’s southern Kenai Peninsula) reported seeing the night suddenly lit up by “a fireball” then darkness. A ship had exploded, he surmised.

But, because of the storm, no attempt was made to investigate. Not until a week later did the passing steamer Rustler sight spars poking above the water atop Eldred Rock. The Rustler retrieved a single, charred body, identified as the Clara Nevada’s “gentlemanly” purser, George Foster Beck.

How many went down with the ship? Sixty-five? One hundred and sixty-five? No one knew, not even the managers of the P&A Transportation Co., as the passenger list was lost with the Nevada.

Although Capt. Lewis’s competency was questioned posthumously because of the fender bending incidents in Seattle and Port Townsend, it was acknowledged that the Nevada’s telegraph cable by which the officers on the bridge communicated with the engine room wasn’t operational. But this hardly excused Lewis who persisted in trying to manoeuvre his ship while so handicapped.

Remember the Maine! became the battle cry during the Spanish-American war and drove the tragedy of the Clara Nevada from the front pages. —Wikipedia

The war of words that followed in Pacific Northwest newspapers soon shifted to newer news stories such as the blowing up, in mid-February, of the American battleship USS Maine in Havana Harbour. There was, however, that nagging question of why the Clara Nevada had apparently blown up in the fireball described by George and Mrs. Beck from their vantage point on the Seward City dock.

Was it the Clara Nevada that they’d seen, and was she carrying dynamite, a legal no-no for passenger vessels?

This didn’t make sense as she was on her return voyage; any illegal transporting of explosives would likely have been on her northbound trip as explosives were marketable in the Klondike, not Seattle. Unless her original cargo remained on board, unsold?

What of her boilers, then? Had they erupted when hit by cold water, moments after she struck Eldred Rock broadside and her tired hull fractured? Although divers were unable to answer these questions in August during their inspection of the sunken ship that showed fire hoses snaking across her decks and coupled to the ship’s hydrants and pumps, a Lloyds of London surveyor flatly dismissed a boiler explosion.

The hoses seemed to indicate that the Nevada was afire before she struck the rock. Some took this to mean that her crew were trying to keep the flames from a cargo of explosives. But the fact that the ship remained more or less intact suggested otherwise.

It was more likely, according to another firsthand inspection of the wreck, that her oil lamps had spilled when she struck, igniting several small fires. Then there’s mention in the Seattle Times that firsthand examination of the wreck just a week after the Nevada went down confirmed no boiler explosion but discovered “evidence of three little fires in the boiler room”.

The story of the Clara Nevada should have ended there but it had, in fact, just begun.

The U.S. Government had responded to her loss by building a lighthouse on Eldred Rock. Almost 10 years later to the day, Lynn Canal was again bludgeoned by hurricane-force winds so strong that they shook the lightkeeper’s perch and it wasn’t until the storm had abated that he dared to venture outside.

To his astonishment and horror, he was greeted by the sight of the resurrected Clara Nevada and, scattered on the sands and in the surf, the bones of her lost company. He buried some of these but, come next day, Lynn Canal had reclaimed the ghost ship.

The next time she made the news was in 1918 when hard-hat diver C.F. Stagger explored her deck with a cutting torch to salvage her copper and brass. He couldn’t get below deck but he was satisfied by a large hole in her side that the Nevada hadn’t been afire when she struck Eldred Rock but sank as a result of the impact.

What of her lost company? It seemed odd that only one body was recovered.

Three months after the Nevada foundered, and seven miles from the wreck site, a passing vessel spotted a boat on the beach. Curiously, they described it as neither a lifeboat nor a sealing boat as would be likely at that time. It contained a life preserver from the Nevada and clothes rolled up in a blanket. Nearby, on the beach, were a second blanket roll and the ashes of a fire.

There was no trace of whoever had made it to land and, again, the Clara Nevada should have faded into history. As well it might have—had not, just a year and a half later, her master Capt. Charles H. Lewis been alive and well and commanding a Yukon riverboat!

The fact that he continued to work for a living seems to contradict suspicions of his having conducted the greatest marine heist in history. He retired to Baltimore and died in 1917 without, so far as is reported, wealth.

He wasn’t the only survivor, apparently. One of her firemen, a supposedly unsavoury character by the name of Paddy MacDonald, was known to be kicking about Nome and two other alleged survivors were reported to have returned to their homes in the U.S. after escaping the wreck in a lifeboat.

* * * * *

And what of the fortune in gold supposedly being carried in passengers’ luggage and in the ship’s safe? Estimates at the time ranged from $160,000 to $300,000—tens of millions of dollars today.

A full century and a-quarter later, the bones of the Clara Nevada remain on the rocky ledge, just 24 feet down and easily accessible by divers. There have been no reports of gold being recovered. Did Capt. Lewis deliberately wreck his ship in shallow water so as to steal her valuable cargo? He’d have needed help, of course. As for the fire, whatever its origin, who knows?

Writer Steven Levi is convinced that the Clara Nevada was deliberately wrecked and that most of those lost aboard were murdered for their gold. If that is so, and Capt. Lewis was involved, wouldn’t he have retired well off? The only clue here, if such it is, is a note in the Baltimore Sun upon his passing that he’d “followed no steady employment” in his final years.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s new Hassler is a coastal mapping vessel—and a far, far cry from its ca 1871 predecessor Hassler which has earned immortality as a ghost ship. —NOASS photo