From Seafarer to Sawmiller – The Story of Carlton Stone and His Hillcrest Lumber

(Based primarily on Carlton Stone’s Hillcrest: A History of Vancouver Island’s Hillcrest Lumber Company by Duncan author/historian Ian MacInnes. This is the fist of two parts.)

Even today, 72 years after his death, Carlton Stone is a legend in the Cowichan Valley.

The legendary Cowichan Valley sawmiller Carlton Stone.—Hillcrest Lumber Co. Ltd. Employees Reunion Newsletter – The Last Whistle

Like his immediate neighbour and fellow sawmill owner Mayo Singh, he’s fondly remembered as an enlightened employer who built a thriving business without ever forgetting the welfare of his employees.

Hillcrest Lumber Co. did have labour disputes over its 55-year history. But nowhere near as many nor as bitter as those of its competitors. Built immediately after the Second World War, Mesachie Lake was intended to be and, by most standards succeeded in being, a model community.

Carlton Stone’s life journey began on Oct. 11, 1877 near Kirby-le-Stoken, Essex, England. Despite being born of a traditional farming family, he wasn’t drawn to the land. Instead, aged 14, he found work as a seaman aboard a barge. Seven months later, with a glowing recommendation as a “very diligent, honest, steady, trustworthy young seaman,” he signed aboard a coastal freighter.

Then he made three voyages Down Under.

Fortunately, the young seaman kept a journal; he even tried his hand at poetry. But, for the most part, his daily entries were cryptically brief although they can be intriguing, such as that for April 27, 1896, when he noted that a heavy northwesterly squall had slashed the barque Maquarie’s sails and bent her masts “like coach whips”.

After six years at sea he had, as he’d tell his grandchildren, circled the globe twice before he could shave. He was 21 years old when he returned to Essex to work, for the next five years, in a relative’s machine shop. Again becoming restless, and having read glowing reports of Canada as a land of opportunity where industrious settlers would be given 160 acre of prime farm land, he left his homeland for the last time and landed in Montreal in May 1904.

But five months as a farm hand in Manitoba were enough to send him to Vancouver where he went to work in a sawmill. At last he’d found something he liked, something with, he thought, a future.

It would be years of hard work before Stone founded Hillcrest Lumber Co.

After working his way up to millwright, he found the means to start a small mill of his own in North Vancouver. It proved to be an inauspicious beginning. Hardly had he begun cutting timber than a bush fire swept away his little mill. Nothing could be salvaged, he had no insurance. What to do?

Stone chose to try again, this time on Vancouver Island.

He arrived in Duncan in 1909, then within three year of incorporation as a city and little more than a gaggle of false-fronted stores, a couple of hotels, a few score homes and a railway station. He couldn’t have been broke, despite his Mainland disaster, as he was able to buy the inventory of a defunct lumber company, and the C. Stone & Co. was soon advertising “odd lots of lumber at ridiculously low prices”.

Over the next three years he worked as millwright, shipper and carpenter before entering into partnership with ‘Two-Bit’ Henderson to build a small steam-powered sawmill on Kelvin Creek near today’s Fairbridge residential community, Cowichan Station.

With two Chinese labourers and Henderson’s expertise, Stone embarked upon a crash-course in logging. Author MacInnes describes their method of getting the downed timber—gargantuan first-growth fir, hemlock and cedar—as much as half a mile to their mill, which was built over the creek.

“They constructed a pole ‘railway’ that sloped gently throughout its length toward the mill, its two parallel ‘rails’ consisting of large poles laid end to end and fastened with ties. A pair of locally built wagons with bell-flange wheels simply coasted down down these rails to the mill pond. The wagons’ descent was regulated by using brakes and the ascent achieved by using a horse to haul them back up the incline to the woods.”

As crude as it sounds, it worked!

Which is more than could be said for their mill which, built of recycled machinery, gave the partners continual trouble. Nevertheless, they persevered and, ever so slowly, with Stone acting as salesman, began to prosper. By mid-1913 they were cutting 12,000 board feet a day and, showing for the first time that he had a vision, Stone began to eye oversea markets.

Perhaps this was too much for the two-bitting Henderson who bowed out by selling his share of the business to Stone and becoming a minister. On August 10th, with the former sailor from Essex again on his own, a newspaper advertisement formally announced the birth of the Hillcrest Lumber Co. C. Stone, proprietor*.

(*Stone was hardly being original; if you Google ‘Hillcrest Lumber’ you’ll find companies doing business under this name throughout the continent.)

One of the most successful carers in Cowichan Valley logging and sawmilling history, one that would make Carlton Stone wealthy and a local legend, was truly underway...

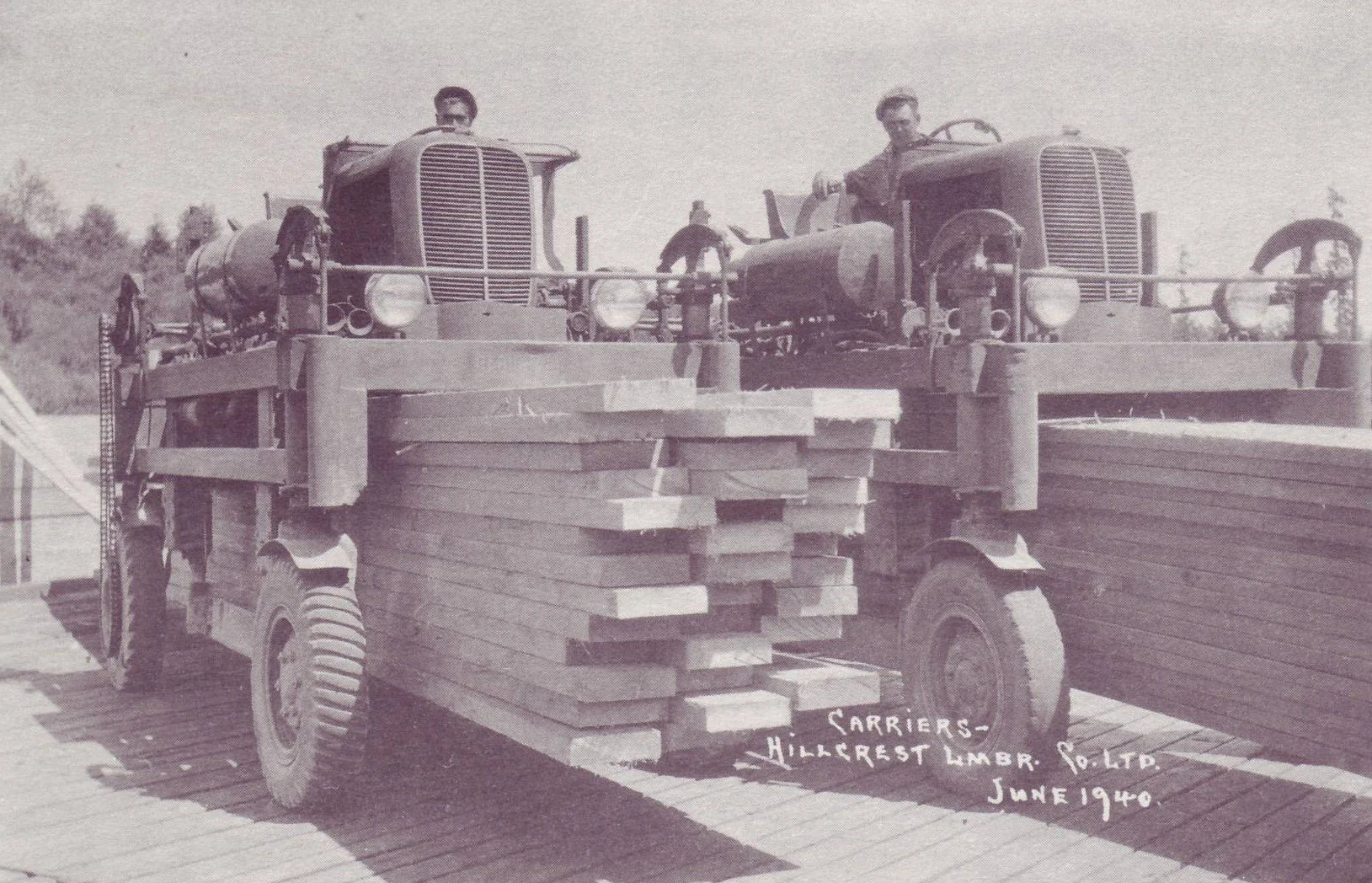

By 1940 when this photo was taken of these lumber carriers, Carlton Stone had come a long, long way from the home-built gas-powered locomotive that looked like an outhouse on wheels. —Author’s Collection

After buying out his partner and launching his new company, Stone made a trip back to the Old Country to attend his brother’s wedding, where he met Ellen Mathias, the bride’s first cousin. They corresponded upon his return and, in 1914, married and moved into a large house he’d built on Eagle Heights where they’d begin a family of six children.

By this time the Doupe road sawmill had run out of timber so, in 1917, Stone relocated to Wheatley Siding, Sahtlam, on the E&N’s Cowichan Lake branch line. With direct railway access to national markets, the new mill would be bigger and more productive.

This required a better private railway system than at the old site and Stone showed his ingenuity and machinist’s background by building a small, gas-powered locomotive.

Despite looking like an outhouse on flanged wheels, it could haul as much as 3500 board feet of logs.

To finance all this, he’d had to find investors, but it only took him five years to buy out his principal partner, two smaller investors remaining on the books for some time longer. Although historian MacInnes couldn’t verify it, legend has long held that Chinese foreman Sue Lum Beng bailed out the company from time to time.

The Hillcrest operation continued to expand to meet the demands for Prairie and eastern markets and, with the First World War, to mill spruce (from an unknown source as it’s not native to the area) for aircraft production. By July 1919 the Stone operation was overtaxing the E&N’s rail car capacity. A further sign of production—and prosperity—was the purchase of a ‘real’ locomotive, a new Shay.

With 72 employees the town site which had come to be known as Hillcrest continued to grow.

A private residence and, at right, the concrete vault from the lumber company’s office now mark the site of the Hillcrest Lumber Co. at Wheatley, Sahtlam.

Those who knew him described Carlton Stone as a “restless, tireless dynamo, a hands-on sort of man”. He also seems to have been a good salesman although a selling trip to China in 1921, while showing enterprise, seems to have failed. Through the ‘20s, despite occasional market contractions, he managed to steadily expand production and to improve his product lines by installing the latest in kiln-drying and milling equipment.

This allowed Hillcrest Lumber to play a leading role in demonstrating B.C. wood products at an Empire Exhibition in London.

Another milestone for this period was the enactment of the eight-hour work day, as of Jan. 1, 1925. Stone not only met the challenge of a shortened work day by completely revamping his mill and installing state-of-the-art equipment and larger steam boilers, he almost doubled production. Workers had no sooner finished finished the job than fire broke out in the boiler room and likely would have consumed the entire mill had not master mechanic W. Ferris organized a spirited hose brigade.

Within a week, it was almost business as usual although the boiler room needed rebuilding.

Legislation again intervened in 1926 with a 40-cents-per-hour minimum wage but doesn’t seem to have impacted on the Hillcrest Lumber Co., Carlton and Ellen having taken their six children and a nursemaid on a four-month-long visit to the Old Country.

Even with increased production and a larger work force, the Hillcrest operation was known for its safety record in an industry that was notorious for its workplace fatalities and injuries. There had to be exceptions, of course, such as that which claimed the life of hook-tender Arthur Williams in May, 1927.

Slash and forest fires were a danger over the years, too, and there were other seasonal impediment such as snow, but Hillcrest Lumber continued to prosper. With Stone pouring money back into larger, up-graded equipment and infrastructure, by 1928, his company was the Island’s third largest producer.

Having exhausted its Mount Prevost timber limit, operations shifted to 14,000 acres north of the Chemainus River.

It took months for the Great Depression, officially begun in October 1929, to make itself felt as American and domestic markets dried up. By May 1930, with the mill shut down and scores of workers and their families depending on him, Stone headed to Britain in search of orders, only to find that the market was flooded with subsidized Soviet lumber.

He decided to make the greatest gamble of his career by investing every penny he could borrow to buy a revolutionary new Swedish gang-saw that was capable of extremely accurate cuts, and to build a new dry-kiln. The saw would allow him to penetrate the exacting British market and freight, one of his greatest expenses was based upon weight—dried lumber would weigh less and cost less to ship.

In the 1970s, Andy Bigg, publisher of the Duncan Pictorial, regularly ran photos submitted by readers, among them this shot of the No. 2 Shift of the Hillcrest ‘Swede Mill,’ in June 1940. It was one of many great logging scenes submitted by George Menzies of Vancouver.

Despite these improvements and despite the government having suspended the minimum wage act which enabled him to reduce his payroll substantially while still paying living wages, Hillcrest Lumber lived day to day until August 1932 when all operations ceased.

1933 was marked by a partial return to work, a rush of injuries on the job, a fire that devoured a cold-deck of uninsured logs, and a one-day strike, before the mill resumed running full shifts. Other challenges and six more years of Depression lay ahead before the Second World War revitalized B.C. industry.

Always known as a benevolent employer who was willing to invest in improved technology, he tried to keep most of his men working but, by late 1934, he’d been hurt by two fires and he was up to his ears in debt. With British sales all but dried up, even Stone had to bow to the inevitable by laying off his 450 employees.

Typically, he allowed them to continue living, rent free, in their company houses.

He’d hardly returned from a personal sales tour of Britain than he was off again, this time with two other leading lumber producers who, with Stone, comprised 90 percent of the B.C. market, and who shared his view that they could penetrate the British market which had previously been flooded with subsidized Soviet lumber.

But it was Japanese orders that sent Hillcrest’s men back to work, early in 1946, despite snows and labour difficulties that beset other operations. Then October delivered a personal and professional blow with the untimely death of Stone’s sawmill manager and friend J.D. Pollock, after an association of 24 years.

Somehow Hillcrest Lumber made it through 1937-38 with a reduced workforce in a Cowichan Valley that depended upon the woods industry for fully 60 per cent of its economy.

Ironically, the world war that brought horror and devastation to much of Europe brought a return of the ‘good times’ to the B.C. woods industry. Orders for Hillcrest products had increased early in 1939, only to be stymied by sporadic snowfalls that continued into April, followed by unseasonably high temperatures that again closed the woods.

Author MacInnes noted that part of the credit for this return to production was Stone’s having, after years of lobbying, persuaded overseas markets that precision-milled hemlock could compete successfully with Baltic products.

Then came a problem of shipping despite the use of trans-Atlantic naval convoys and, with significantly increased production costs, it was glumly predicted that the lumber industry—resurrected so dramatically after 10 years of Depression—likely wouldn’t show a profit.

On the personal front, Carlton Stone was having problems, too. He was 62 years old in November 1939 when he became so ill that he required months to recuperate, including time spent in the sunny clime of Jamaica. The old work horse had had his first notice that he wasn’t indestructible.

Despite a continuing shortage of ships, local mills achieved record production levels because Britain, in desperate need of military construction, could no longer secure Scandinavian and Russian lumber products. The same urgency applied to Canada and the peacetime American market (which, all these years after, seems to be as much a curse as a blessing to B.C. lumber producers) also warmed up.

This high demand presented Stone with another problem—he was running out of timber.

He proposed re-establishing, for a third time, at Mesachie Lake where he was assured of a 25-year timber supply although it meant that he also would have to create an entire community for his workers and their families. The internment of Japanese-Canadians—including Hillcrest’s entire falling and bucking crew—after Japan entered the war, was partially addressed by the successful implementation of the power saw.

Another implementation of sorts was a vote by Hillcrest employees to join the International Woodworkers of America.

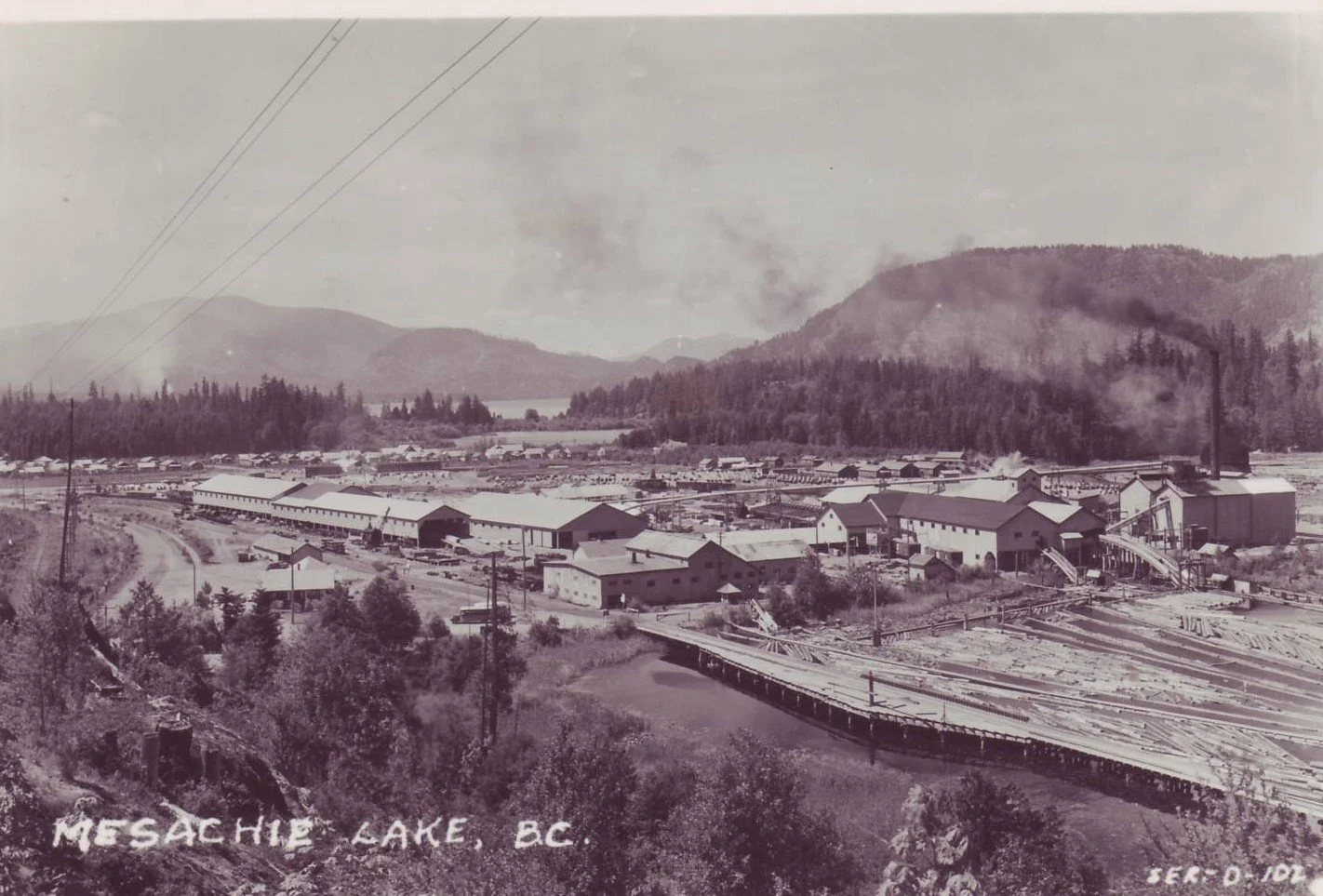

A postcard of the Mesachie Lake mill by well known Youbou photographer Wilmer Gold. —Author’s Collection

In the spring of 1942, Hillcrest Lumber set to work to build a sawmilling community on a flat between Mesachie and Bear lakes. Hundreds of acres were cleared and levelled, streets surveyed and construction begun on a power plant capable of supplying both mill and town site.

All the while, logging operations continued on Mount Brenton. Within eight weeks of shut-down, a fire consumed two cold-decked piles of logs and damaged equipment over a two-week period. Worse, it claimed the lives of two young Lake Cowichan men. They were driving back to camp from firefighting duty when a 90-foot snag crashed down in front of their truck. Unable to stop in time and without seat belts, they were thrown against the dashboard with such force that they died on the spot.

It’s a sad end to Hillcrest Lumber’s Sahtlam chapter.

Carlton Stone’s Hillcrest, by Ian MacInnes, is on sale in the gift shop of the Cowichan Valley Museum.

(Conclusion next week.)

* * * * *

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.