From Seafarer to Sawmiller – The Story of Carlton Stone and His Hillcrest Lumber

Conclusion

(Based primarily on Carlton Stone’s Hillcrest: A History of Vancouver Island’s Hillcrest Lumber Company by Duncan author/historian Ian MacInnes. This is the conclusion of two parts.)

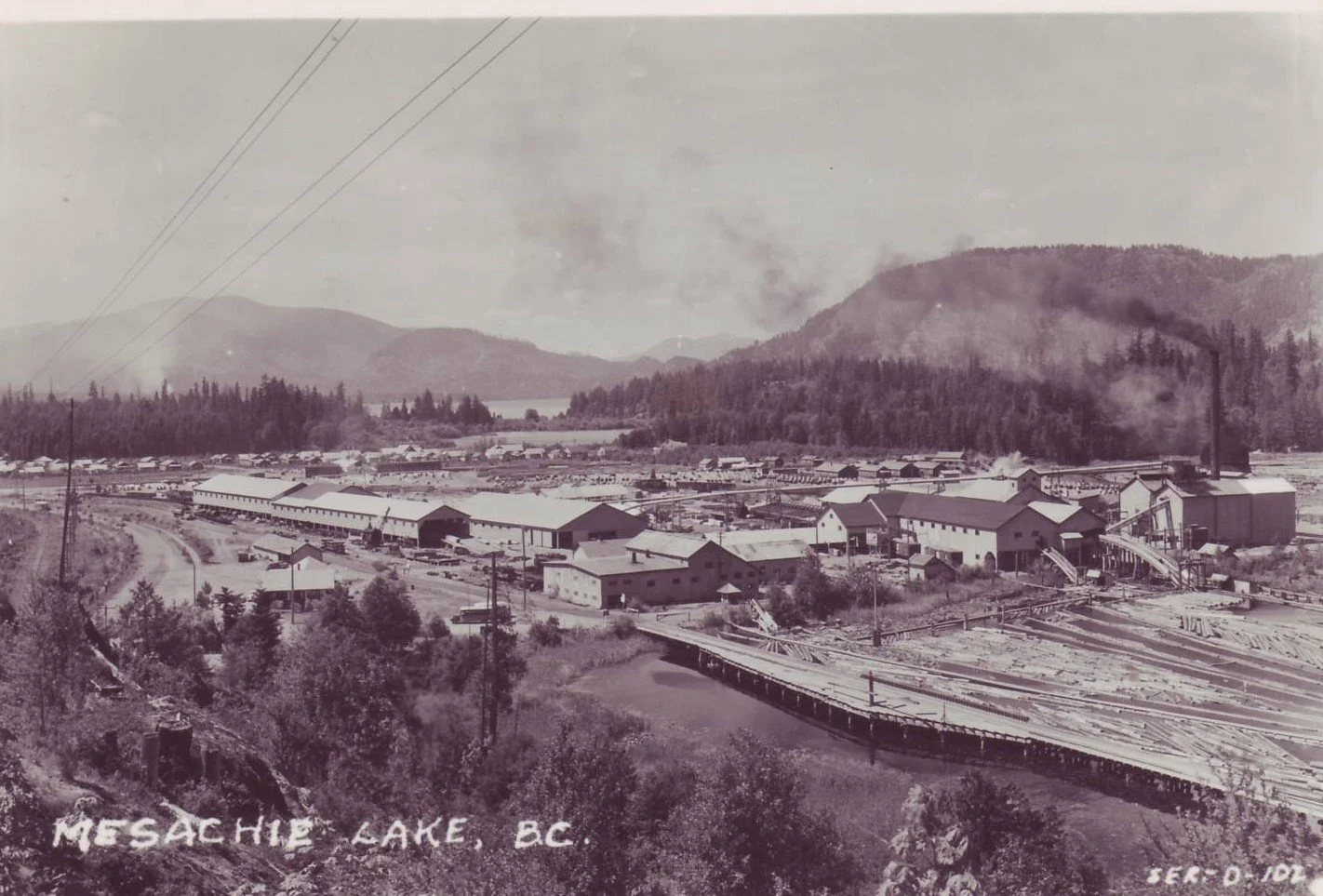

Not everyone viewed the removal of the Hillcrest sawmill to Mesachie Lake in a positive light. In October 1942, months after work was begun, a delegation of Stone’s workers who disliked commuting and didn’t want to move to the lake, urged him to mill logs from the new timber lease at the existing Sahtlam mill.

Sawmill giant Carlton Stone. —Hillcrest Lumber Co. Ltd. Employees Reunion Newsletter – The Last Whistle.

As this wasn’t economically viable and would contravene a condition of his timber lease, Stone, who was well-regarded for his consideration of his employees, stood his ground and carried on building his ‘dream mill.’ This, noted MacInnes, required the moving of an entire industrial work site and community that was three-quarters of a mile long!

With Canada at war there was a shortage of able-bodied employees, including sons Norman and Paul in the military, but with the help of younger sons Hector and Gordon, and a cadre of long-serving Hillcrest Lumber veterans, the great move was begun.

Even as the last log was cut at Hillcrest, Oct. 29, 1942, crews were tearing down the mill.

Over following months, “the immense task of moving the main, Swede and planer mills, the lumber sheds, the dry kilns, machine shops, bunkhouses, mill houses, cook houses, boilers, burners, stacks, trains, trackage and tons and tons of bits and pieces somehow came to pass.”

Even the 80-foot-high smokestack was cut into pieces for the move, as were the beehive burners and employees’ homes for reassembly on new foundations. In all, 200 rail cars were needed to complete the transfer via the E&N’s branch line to Lake Cowichan, thence to Mesachie Lake by trucks.

It was more than a matter of recycling the old mill, however.

A 10-foot Sumner band saw replaced the circular head saw and some equipment formerly powered by steam was switched to electricity. Even as the work was done by a 100-man crew who commuted daily by bus, fallers were busy and logs were accumulating in the millpond. New 12-room bunkhouses with steam heat, showers, a drying room for wet clothing—and a ‘flunky’ to clean up—were built, with separate bunk and cook houses being constructed for East Indian and Chinese employees who preferred their own accommodations.

By this time, several families, including the Traers, Abernethys, Francises and Horsfallls, had moved into their ‘new’ homes, with the Traers achieving the distinction of having the first vegetable garden.

Aug. 9, 1943, “the great machine came to life when the chain carried the first log up the chute to where the new Sumner band saw cut it into lumber,” writes MacInnes.

A disappointment for Stone was the July 1944 fire, his company’s worst, that consumed 150 acres, 3 million feet of felled and bucked timber, and two gasoline donkeys. It occurred at a time when orders from Britain, which faced the need to build 600,000 homes, were at their all-time highest, although much of Hillcrest’s production was being consumed by Allied engineers in France, Holland and Italy.

Nevertheless, Stone’s model community at Mesachie Lake continued to grow, with the addition of a community hall and company store, and landscaping was encouraged by an example set personally by Carlton Stone. The company also saw to milk delivery and garbage pickup.

Twice in 1945—V-E Day and V-J Day—all work at Mesachie lake ceased and, for five weeks the following year, when the entire industry was idled by a strike for improved working conditions, union security and a shortened work week. Typically, Stone let the strikers remain in the bunkhouses and to take their twice-daily meals at the cook house. Then it was back to business, completion of the new Swede mill and, for Carlton and Ellen Stone, a well-deserved holiday in Mexico.

In September 1946 the tireless mill owner was honoured as “an outstanding pioneer in the British timber market”.

* * * * *

How do we measure a person? Carlton Stone made a fortune during his 40-year long sawmilling career in the Cowichan Valley. That made him successful but not necessarily memorable.

No, there was much more to this onetime seaman from Essex, as shown in Ian MacInnes’ Carlton Stone’s Hillcrest. Highly regarded as a benevolent employer, Stone was a visionary who foresaw his chosen industry’s future, who was his own best salesman, and who had the life-long courage to invest in the best of technology, often at considerable financial risk.

He built the community of Hillcrest at Sahtlam then tore it down and built anew at Mesachie Lake. That mill, too, has faded into history but his postwar subdivision of 100 homes, built for his employees and their families, survives.

Too, there’s St. Christopher’s Church, Stone’s lasting contribution to his Anglican faith. Previously, St. Peter’s, Quamichan, had benefited from his magnanimity. The late David Ricardo Williams devoted four pages of Pioneer Parish, his history of St. Peter’s, to Carlton Stone’s proactive work. When a proposal in the 1920s to enlarge the church encountered stiff resistance, Stone, who wanted a vestry large enough to accommodate an organ, had had to lobby hard.

He and other like-minded church members finally prevailed although they had to compromise on the organ. Not until 1965, long after his passing, was one installed.

Williams recalls how the “formidable” Stone somewhat intimidated Canon T.H. Hughes who, aware of Stone’s command of the Bible, would sometimes leave the church by another door rather than chance being challenged for something he’d said in his sermon.

The Stone family connection continued with son Hector who was baptized at St. Peter’s and who served as its Warden Emeritus until his death. It was the senior Stone who, in April 1919, oversaw the erection of St. Peter’s war memorial from a granite boulder that had to be sledded for almost a mile to its present position beside the church.

Estimated to weigh between 10-12 tons, it was winched onto its side then rolled onto greased skids for the days-long, horse-drawn journey to St. Peter’s. Parish minutes give full credit to ‘Mr. C.Stone,’ under whose supervision the “transportation of the rock was carried out without any accident or mishap, and without any damage to the road”.

That August, 450 people attended the memorial’s dedication service and watched as Carlton Stone removed its covering Union Jack.

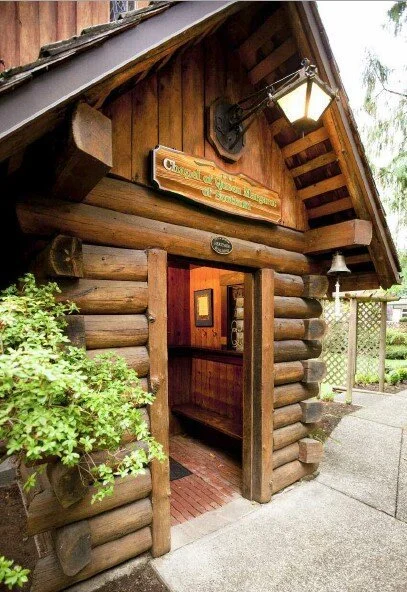

It was at St. Peter’s, 31 years later, that one of the largest funerals in the church’s history was held for its longtime supporter who’d passed away at the just-turned age of 73. In a plain casket of yellow cedar, the sawmill pioneer was borne to his final resting place under the trees by sons Hector, Norman, Gordon, Peter, Paul and son-in-law Ted Robertson. A memorial service was held three days later at Mesachie’s St. Christopher’s Church, the church that Stone had built and which had been described as one of the most beautiful in the Anglican diocese.

“It is difficult to imagine a more fitting scene than that of homage being paid to Stone by his own people in a church that he had given the community,” wrote MacInnes.

Alberta Wright later wrote of the service: “...To those who knew him and loved him, his kindly smile, twinkling eyes, and love for his fellow man will be a memorial in our hearts. He was a true Christian.”

Hillcrest Lumber Co. carried on under the management of Carlton’s sons. By then logging trucks had replaced logging trains and, in 1959, the once-revolutionary Swedish gang-saw that had saved the company’s bacon almost 30 years before, was replaced by a more productive machine. That same year, Ellen, Carlton’s widow, passed away, aged 80,

It all came to an end in 1968 when Hillcrest Lumber, unable to acquire more timber, shut down. On August 6th the band mill cut its last log, and the gang mill five weeks later. Today, Carlton Stone’s community of Mesachie Lake lives on, the mill site having been returned to its natural state as a church campground. Without doubt, this would please the lumber baron of old.

* * * * *

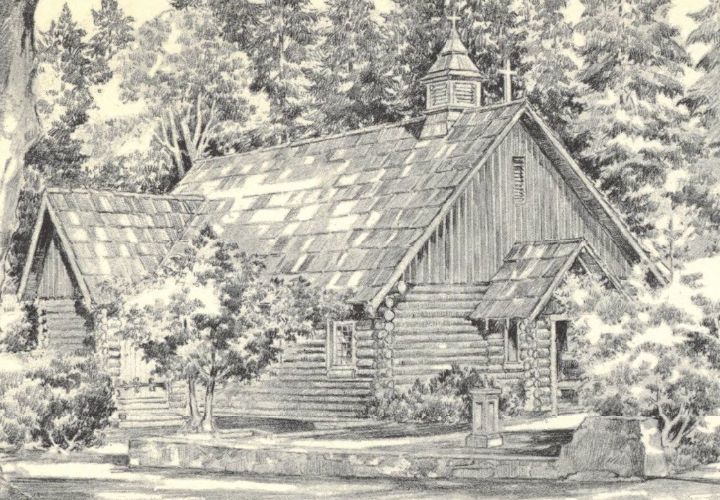

The rustic Queen Margaret’s Chapel, 660 Brownsey Avenue, one of a series of 1950s postcards by artist Edward Goodall.

Not as well known is yet another Carlton Stone legacy, Queen Margaret’s Chapel.

The Misses Nora Creina Denny and Dorothy Rachel Geoghegan founded Queen Margaret’s School with a first class of 14 boys and girls in 1921. What began as a common interest in the Girl Guides movement led first to their friendship then to their partnership as teachers-operators of what has become an internationally recognized co-educational private boarding and day school, now operated as a non-profit organization by a trust company.

On Nov. 16, 1933, the Cowichan Leader reported upon the completion of the school’s log chapel: “Financed almost entirely by donations and entertainments, the new Queen Margaret’s School Chapel is a monument to the generosity and loyalty of the school and the parents. Old Girls and friends who sent money assisted with entertainments, and material or actual labour.

“Possessing such a fine background, the chapel is also unusual from an architectural point of view. It is a log structure, but instead of the usual manner of construction, in which round logs are made to fit at the corners by dovetailing, the fir logs used were squared on three sides and built so that a rounded exterior is seen, yet the logs fit squarely together.

“Instead of being grooved at the corners, they were fitted by a system of drift-bolts, which are invisible when the logs are in place and also allow for expansion or settling.

“The idea of using this style of architecture came from Mr. [Carlton] Stone, who also arranged the drift-bolt system with special regard to the needs of the chapel. He went to the trouble of erecting a piece of wall at Hillcrest [site of his large sawmill] for demonstration.

“Mr. Douglas James was the architect and Mr. O.C. Brown contractor. Building operations were commenced on July 18 and, from then until August 23, seven men were employed continuously, except for one week. There is diagonal hemlock lining in the roof and the beams inside are peeled fir poles...

“The building is 20 feet by 60 feet, exclusive of the vestry, and will accommodate 120 persons. The top of the bell tower is 25 feet above the ground and the top of the wall 18 feet. The material came from Hillcrest [Lumber Co.], including specially-cut timbers which were tongued and grooved for the gable ends.

“It is hoped that sufficient funds will be obtained to put down flooring, insert windows and provide the necessary furnishings by next summer.

“As the work already completed is all paid for, the dedication may be expected before the end of the school year. A harmonium has been promised by the Rev. A. Bishlager and tapestry depicting the life of Queen Margaret, which is to be placed around the walls, is being made by the school...

“Miss N.C. Denny attaches a sentimental value to the first contribution received, as it came from her old school, Queen Margaret’s, Scarborough. Shawnigan Lake School also sent a contribution, which included the proceeds of a chapel collection...”

As the Chapel appears today. —Queen Margaret’s School

* * * * *

We have to settle for the gateposts for Carlton Stone’s second mansion.

The imposing 80-year-old stone pillars with their bronze plaques at the Gibbons Road entrance to what was his 1926 manor, and the name of an upscale subdivision, are all that’s left of Stonehaven. This was the manor house designed by prominent Cowichan Valley architect Douglas James and built by the renowned Oscar Brown.

Swept away, too, is the lumber baron’s arboretum of exotic trees, along with the eye-catching water tower—virtually everything, in fact, that made this hidden property beside Cowichan District Hospital a private park, a landmark and a gem. In their place are expensive homes, many of them with so-called ‘arts and crafts’ styling, and cheek-to-jowl, as is the style of modern subdivisions where no one, it seems, wants to garden any more.

And no one spoke up for Stonehaven’s obvious heritage value.

Happily, Carlton Stone’s first fine home, 5373 Miller Road, is in the loving hands of heritage restoration expert David Coulson and wife Ulla.

5643-square-foot Stonehaven sat on 12 acres adjacent to the hospital. Primarily Tudoresque with the ‘Craftsman style’ touches that were popular at the time, the two-storey house had a single front gable, stucco wall cladding with decorative half-timbering. A unique touch was in the open-entry porch which utilized ‘ships’ knees’ (naturally twisted tree roots or limbs used in wooden ship construction).

Front and back doors were board-and-batten, arched and utilized heavy iron hardware, windows were multi-paned or leaded, the red roof tiles imported from Europe.

Another distinctive feature were the chimneys’ three separate flues, set at an angle to each other in a common base.

Originally, five fireplaces provided the only heat. “The large stone fireplace in the living room had Mr. Stone’s special touch,” Cowichan Heritage Society researcher Sylvia Scott found. “He had a stone protruding on either side so [he] and Mrs. Stone could put their feet up...and warm them.” Unfortunately, when central heating was installed in 1944, the decorative hemlock and fir panelling shrank.

Some of Stonehaven’s furnishings were specially-crafted by George Savage of Cowichan Joinery from woods provided by Stone. Thought to be most outstanding of these was an arbutus dining table which seated 14. There was also a sideboard of native dogwood and a “great maple table” in the kitchen.

Even the garden showed evidence of Stone’s interest in exotic trees, which included a large redwood, from around the world.

To encourage the growth of his fruit trees and grapes, he had a 50-foot-long, eight-foot-high brick wall built to provide them warmth. Stone, bricks and wrought iron forged at the company mill were used extensively for lamps and garden ornaments.

In a circa 1934 bake house, a log cabin, all bread for the Stone household was baked each Monday.

In 1940, son Hector and his wife Mary built another, smaller house on the property. In 2004, work was begun on converting this historic site, described at the time by one of its developers as being “just unbelievably gorgeous,” into single-family lots.

The demolition of Stonehaven itself, still solid and sound beneath its tile roof, began six years later.

* * * * *

It's one of Cowichan's unsung 'landmarks,' tucked away as it is in rural Sahtlam on what was the historic Hillcrest Lumber Co. mill property.

The cemetery at Hillcrest, at the entrance and looking west from the top.

An original gatepost almost hidden in the undergrowth.

Situated immediately beside the Cowichan Valley Trail, the former E&N Lake Cowichan Subdivision, it consists of just over nine acres (3.8 hectares) of open, sloping ground. In recent years, thanks to the direction of and financial support from the Chinese Community Ass., the hard work of the DCC's Tommy Moo and community volunteers Neil Dirom, Tim Spenser and Leigh Hirst, it has underwent a thorough clean-up and documentation of its occupants in recent years.

This is the Old Hillcrest Chinese Cemetery. (For background information I'm obliged to Neil Dirom and to Wai Dai (Willie) Chow of the DCCA). They reminded me that, “Before 1947 Canadian citizens or immigrants of Chinese origin living in Canada faced many restrictions—men were unable to marry; when they died there was no family nearby to care for their burial or care for their grave...”

Thus it was that, in 1945, Wah Sing Chow and Sue Lem Bing (aka Sue Lem Bing Jung, Chung Mui Jung, Jung Jong Moy) approached sawmill owner Carlton Stone, seeking land for use as a cemetery for the Chinese employees. Stone graciously obliged and, for legal purposes, ownership of the property was made over to Sue Lem Bing “for the local Chinese community for a final resting place for the Chinese men”.

Two of the headstones, all of which are more or less flush with the ground.

This and at least one other headstone appear to have been vandalized.

Volunteers give up a Spring Saturday to cut the grass at the cemetery.

The provincial government approved the site for use as a cemetery in September and Fong, Kai Wing became its first interment nine months later after he was fatally crushed between two logs on the mill's log deck. His would be the first of 127 recorded burials here, the last being that of Yong, Quon Lain, on Oct. 10, 1968.

That said, it's known that 124 graves are occupied, the remains of three persons having been removed to other cemeteries.

It's noteworthy that all of Hillcrest's occupants were from China's Kwantung province. Their occupations included mill worker, bull cook, logger (railway tie maker), logger (faller), gardener, laundry worker, cook, teacher, boiler engineer, lumber piler, janitor, farmer, barber, merchant, chain puller, saw filer, boom man, accountant and shoemaker.

Some of these occupations were hazardous as evidenced by old newspaper clippings that relate the deaths of Jung, Yin Wing, Fong, Kai Wing, and Boo, Sing Bun, all of whom were killed on the job in the Youbou sawmill, in 1944, 1946 and 1952 respectively.

Ironically, former mill worker, restaurant owner and cemetery owner Sue Lem Bing, who died in his centennial year in Cowichan District Hospital in December 1989, isn't among those buried in the Hillcrest cemetery. He's in Forest Lawn Burial Park in Burnaby after having worked in the Hillcrest mill from its opening in 1942 until its closure in 1968.In February 1992 his estate transferred the land in trust to the Chinese Community Ass. For $1.

In February 1992 his estate transferred the land in trust to the Chinese Community Association For $1.

But not without the DCCA having had to go to the Supreme Court, at considerable expense, to argue that “the charitable trust created for the cemetery purposes with respect to the said lands shall be deemed to have continued and not failed and that the title to the said lands [be] declared to be in trust by the Duncan Chinese Community Ass. in their capacity as Executors for charitable purposes for use as a cemetery including a guarantee given for care and maintenance under the provisions of the Cemetery and Funeral Services Act, S.B.C.”

Further expenses included having the deed registered and the land surveyed. As it happened, all costs were handily recovered by logging some of the mature trees on the unused acreage of the cemetery.

Rather a poetic touch, considering Hillcrest’s history as a major sawmill.

Besides cleaning up the cemetery, which has been quite a task, the DCCA has documented all of the interments (an invaluable undertaking in itself) and has committed to “formally [pay] respect to the pioneers annually and [to continue] to maintain the cemetery”. Another project in the works is to repair and upgrade the iconic wooden archway at the entrance to the cemetery.

In April 2014 Dr. Pamela Shaw, Vancouver Island University, prepared a land use report for the cemetery for Dr. Imogene Lim of the university's Anthropology Department. After this was submitted to the DCCA it was decided to continue to maintain the cemetery.

In February 2015, the Duncan CCA submitted nomination forms to B.C. Heritage for the Old Hillcrest Chinese Cemetery as a 'B.C. Heritage Place'.

P.S. Those who visit Old Hillcrest Chinese Cemetery will find that the headstones are all inscribed in Chinese. The DCCA has a complete register of those interred here and it's to be noted that Chinese write their last name first (as in a directory), i.e. Jang, Chong Wing.

Visitor to the B.C. Forest Discovery Centre can see yet another Carlton Stone Legacy, the beautiful No. 9 locomotive from Mesachie Lake logging days.

Ian MacInnes’s history of Carlton Stone is available in the gift shop in the Cowichan Valley Museum.

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.