‘The Strangest Funeral Procession Ever’

“The strangest funeral procession that ever passed on earth.”

So said Father Henry ‘Pat’ Irwin, Kootenay’s unofficial saint, of the 1885 avalanche that buried a 16-man train crew. Ten were rescued but six were buried alive and Irwin was referring to the super-human efforts he and nine others made to return one of the bodies for proper burial.

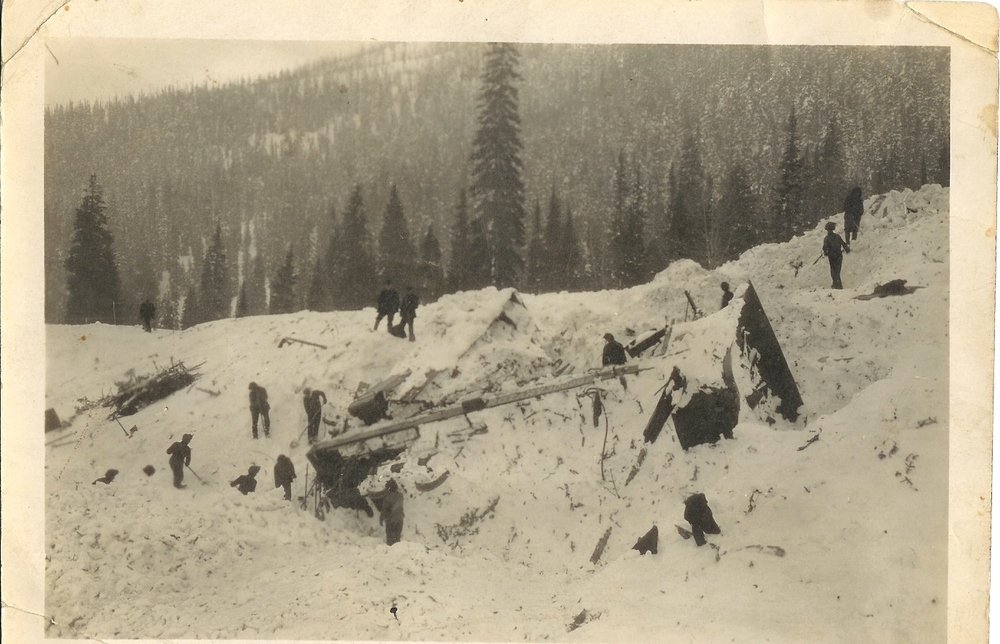

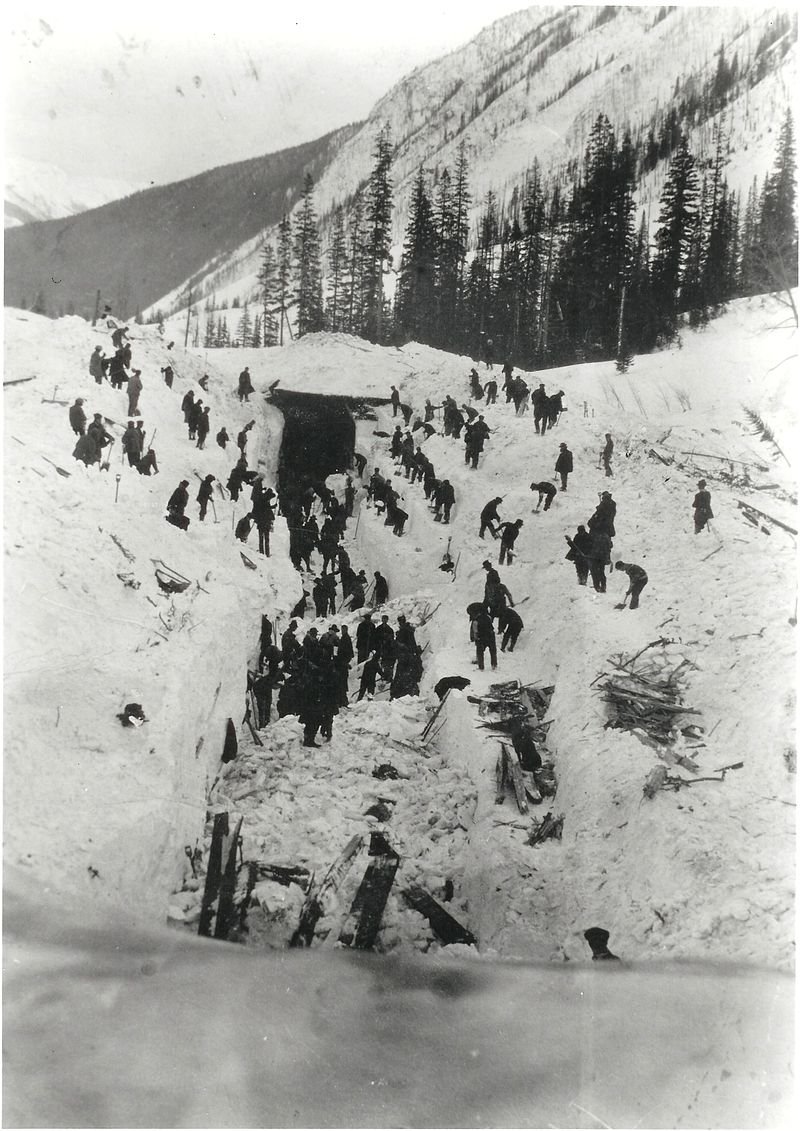

A search for bodies from another avalanche, this one in Rogers Pass in 1910 which claimed 58 lives. —Revelstoke Museum

It was all in a day’s work for one of the most amazing pioneer men of God that British Columbia has ever seen.

* * * * *

Of the many extraordinary men who pioneered the British Columbia wilderness as missionaries, surely Father Pat was the most extraordinary of them all. To this day he’s fondly remembered and so many stories have grown around him that it’s difficult to separate fact from fiction.

But there's no disputing that Henry Irvin Irwin was every bit as colourful and as exciting as the legends. In fact, of him it could be said that he was bigger than life.

‘Father Pat’ Irwin, who became a legend in his own lifetime, was only 42 when he died. — https://www.kootenayanglican.ca/pages/father-pats-biography

Although his Christian name was Henry, and he was an Anglican rather than a Catholic, the miners christened him Father Pat because he was Irish. For that matter, Irwin treated one and all equally, regardless of religious belief. and when, as occasionally happened, he met a skeptic who chose to argue his case with his fists, Father Pat was ready, willing and able to oblige.

Born August 2nd, 1859, the son of a vicar, Erwin was schooled in Dublin to be a missionary, at which time he excelled in sports. This background was to prove invaluable when, years after, and half of world away, he carried the word of God through the wild, woolly and isolated camps of British Columbia.

This career began in 1885 after his service has curate at Rugby, when he was assigned to serve as an assistant to the bishop of New Westminster. Once in the Royal City, he was sent on to Kamloops, where he embarked upon what was to become a lifelong crusade of administering to the spiritual, and often times material comfort of the miners, railway workers and settlers scattered throughout the British Columbia interior.

CPR station, Donald, B.C. —Wikipedia - Musee McCord Museum

With the coming of the Canadian Pacific Railway, the boom camp of Donald had appeared on the map and it was in this sprawling, bustling settlement that Irwin built a church. And it was near here that he recorded details of " the strangest funeral procession that ever passed on earth”.

“I must write you a line to tell you of one of the most weird things you ever heard of and what I have gone through today, " Irwin wrote to a friend one evening. “A few days ago up here in the Selkirks, an avalanche came thundering down Mount Carrol, and came right across the valley and struck the track, turned right upgrade and smashed into two engines and the snow plow, burying them completely, and 16 men with them.

“Nothing was to be seen of them but the end of the plow and the smoke stack of one engine, which was buried up all together.

“Well, the slide came down upon the man who were watching it come down the other side before any of them could escape. Of course, when the few men who were around saw this, they started in digging and got out 10, but six of the poor fellows were killed.

“The man dared not go on digging for long, as avalanches were coming down all around them, and they were in peril of their lives. It was a strange scene, and a heart-rending one, too. They now have got all the bodies out. One of them was the husband of a poor woman in Donald whom I knew. I had to break the news to her and as there was no one to hurry up things, I started for Donald yesterday, and after a ride of 12 miles on an engine, I got to Bear Creek last evening late."

Early next morning, he and his companions had pushed onto the camp where the bodies of the avalanche victims were being kept. With 10 men and the coffin containing the remains of his friend's husband, he began the return trip to town, as further snow slides continued to roar down upon them.

"... I think of all queer frisks,” he marvelled, “this days was the greatest I ever had."

Digging for bodies in the 1910 avalanche. —Wikipedia

Encumbered by their heavy clothing, snowshoes and the weighty coffin, the burial party was forced to run from one snow shelter to another. While keeping close watch on the mountainside, they had to time their sprints between the avalanches, whose thundering roar resembled an artillery barrage and almost deafened them.

Describing these awesome ‘frisks” of nature to his friend, Irwin explained that the avalanches were preceded by roaring and flurries of snow which “always told us when they came... exactly like artillery booming away [with] the smoke curling from the guns, and true to the simile, the great snow or ice balls came thundering down with all the rightful force of cannonballs."

In short, it was a frightened funeral procession that memorable day in the Selkirks.

“Well, " he continued, "we had to climb over slides between the snow slides, and that by a bad trail, over perhaps 30 feet with snow on trees, and you fancy that those 200 or 300 yards did not take as long to make. The scene of the accident was too awful and too weird to describe: all snow around, piled up 100 feet, and they were down in the hole, the engine, and the graves of the poor six, one of whom we had put in a coffin, and start[ed] back along the fearful hillside, and run all the risks again.”

As did all railways, the Canadian Pacific later battled winter snows with more advanced equipment, such as this rotary snow plow. —www.pinterest.com

“That was the strangest funeral procession that ever passed on earth. Fancy avalanches rumbling and thundering around, and 12 men treading across the hills with a coffin swinging on a pole, every man listening for the avalanche above him and going as fast as he could across the 200 yards between the sheds.

“I can tell you, it made one think of the 600 ride into the Valley of Death. However, thank God, we got through all safe, but we don't have to do it again. I'm going to Donald tomorrow with the coffin."

Days later, in a second letter, Father Pat continued his amazing, and hair raising account of escorting the railway man's body to Donald. But, before describing the final lap of his journey, the missionary again impressed upon his friend the horrors of that funeral procession across the snow, and called it the “weirdest funeral that the wildest imagination could paint".

Even at the top at the time of his writing the second letter, when safe in Donald, Irwin continued to relive every terrifying moment of that mad race down the mountain slopes, between snow shed and snow slide.

“You can only think of great, gigantic heights up to 4,000 feet above you, and some 20 feet of snow on the hillside; then to hear the rumbling like a roll of thunder; you see the smoke rolling from guns as the slide rushes into the gulch below you at 100 miles a minute. No place can give you a better idea of the power of nature and the powerlessness of men.

“There was no railroad to be seen; the only things to mark the line [are] the tops of the telegraph holes or the butt ends here and there where they have been turned endwise..."

Suffice to say, each and every man of the heroic party had been relieved and thankful to have escaped from the “Valley of death” without injury. Those waiting for them were also relieved as they’d witnessed three of the larger slides, and had feared for their safety.

As all were aware, there was no rescue for a man caught in an avalanche “as they are as hard as granite and just as heavy”.

On Sunday morning everyone decided that it was safe to begin the 28- mile trek along the railway line to Donald with their grim cargo. Dividing his volunteers into three six-men teams, Irwin stationed them at various locations along the route, each taking turns to pull the toboggan with the coffin to the next relay point.

Father Pat took his turn on the towline or broke trail through three feet of packed snow. Throughout the morning and early afternoon, they struggled on towards Donald at the rate of two miles per hour. At 4:00 they met three locomotives plowing their way up the hill.

On the return trip, the funeral party was able to hitch a ride for eight miles to a way station, where Irwin wired to Donald for another train. Hours later, the relief train picked them up for the run into Donald, arriving about midnight.

The Donald cemetery, final resting place of the unnamed avalanche victim for whose widow Father Pat and volunteers risked their lives. —www/findagrave.com

Sighed Irwin, “That was the hardest Sunday's work I have ever done, and “I hope it will be the last I'll have to [do\ of that kind. Of course, I should not have done it unless the poor wife was here fretting her heart away that her husband's body was lying miles away in the snow.”

Such was the story of “the strangest funeral procession”—and the measure of a wonderful man, Father Pat Irwin.