The Tragedy of Belle Adams

Her only known photo is fascinating in itself. She’s young (23), fair skinned with a clear complexion, plainish bordering on attractive, without makeup and neatly coiffed. She isn’t looking into the camera but slightly upward to her right, as if at something across the room. You can’t read anything in her expression other than that she shows no visible emotion.

Her high-collared dress has a pattern of conflicting stripes and swirls, with puffed-up shoulders.

But it’s her God-awful hat that pulls the eye. It’s a cornucopia of flowers, lace and ribbons. It most resembles a bowl of wax fruit dumped upside down on her head.

Hannah Maynard’s photo of Belle Adams. —Wikipedia Commons

The photo is black and white, of course, because her photo was taken in 1898, and it’s high-res because it was shot with a large format camera by the pioneer Victoria photographer, Hanna Maynard.

Pioneer Victoria photographer Hannah Maynard. —Wikipedia

But Belle’s isn’t your ordinary photographic portrait; she wasn’t Hannah’s client and she wasn’t posing by choice. No, Hannah’s client for this photographic assignment was the Victoria Police Department and the photo in question is one of the VPD’s earliest mug shots.

Belle, you see, was in trouble, deep trouble—the result of what was described as “unbridled passion and mad jealousy”. Which is why I noted the lack of visible emotion in her expression; she appears, in fact, to be completely self-possessed.

Surely, her mug shot was taken shortly after her arrest? If so, she shows no signs of her hysterical state as was described by witnesses and the arresting police officer.

She looks to be anything, in fact, but a murderer.

* * * * *

As Victoria looked shortly after the Belle Adams-Charlie Kincaid tragedy. —Author’s Collection

Journalistic styles have changed greatly over the years so the headline that announces Belle’s encounter with the law is somewhat curious by today’s standards:

BY A WOMAN’S HAND

The subheads are more or less as we’d expect now:

Charles Kincaid the Victim of His Mistress’ Jealous Rage

—

A Johnson Street Hotel the Scene of the Awful Crime

Another curious note is that the report of her having killed her lover begins with a reference to “another of her sex,” Martha Wolff, who was then in a provincial cell after having just been convicted of the murder of Mrs. Charles Marsden.

But let’s stick with the story of ill-starred lovers Bella (sic) Adams and Charles/Charlie Kincaid aka Charles/Charlie Brown.

Her crime, in the words of the Colonist reporter, was the result of unbridled passion and mad jealousy. (We should keep in mind that these were Victorian times with their sanctimonious views of middle class morality, when women were either respectable or reprehensible, with little leeway in between.) She’d been “frenzied by the fear that her unrestrained and unnatural affection for a man not of her own race and colour was no longer returned”.

There you have it: Belle and Charlie weren’t just lovers, they were social lepers, she white, he, black. Worse, she was a suspected prostitute and he her pimp. The gasps and clucking of tongues by shocked and horrified Colonist readers probably tipped the Richter Scale.

Is it any wonder then that Belle, allegedly faced with losing Charlie’s affection after giving up her marriage and child for him, after supposedly selling herself to strangers for him, was driven to almost sever his head with a straight razor?

The scene of the tragedy was a first floor apartment in the lower Johnson Street Empire Hotel (still there today), about 9 p.m., June 3, 1898 They’d obviously quarrelled but the first anyone else knew of this was when Charlie—fatally slashed and bleeding profusely—staggered down the stairs and across the lobby to collapse in the street.

He did this unaided but not alone, a shrieking, weeping and apologetic Belle having followed him every stained footprint of the way. When he collapsed at the entrance to the hotel, she fell upon his “bleeding, quivering body,” took him in her arms while “speaking words of endearment into the deaf ears and pleading for forgiveness and for the life of the man she had struck down...”

By this time a crowd had gathered around. As it was apparent to all that Charlie had expired Belle was allowed to continue to cradle him in her arms until Constable Anderson arrived and placed her under arrest.

Such was the tragic road travelled by the former “Bella” Pettie who the reporter described as being a “somewhat prepossessing” 23-year-old blonde, the daughter of a well-to-do farmer of O’Brien’s Station, Kings (sic) County, near Seattle.

Four years before she’d married a man named Adams and had a daughter but the union didn’t work out and they separated. Belle, having custody of the daughter, joined her mother in the stampede to the Klondike in 1897 (neither of them as prospectors, we can be sure), where Belle was said to have fallen in with bad company.

That’s when she met the man who would be her nemesis, Charlie Kincaid/Brown, said to be a pianist and guitarist in sporting houses (brothels if we must spell it out), for whom she sacrificed her child, her “wifely honour and every remaining vestige of respectability”.

Twenty-eight-year-old George, a widower with two children, was from Kansas City and he’d abandoned a second wife in Nelson, B.C. Belle, who it was said had become infatuated with him upon their first meeting, had accompanied him to Victoria six months before. Life in the provincial capital had been a succession of moves to various living quarters, “the high pressure life inseparable form such an association,” in the unctuous prose of the Colonist.

But Charlie seems to have had a roving eye and soon they were quarrelling, loudly and publicly, with Belle threatening, should he leave her, to take his life and her own.

This hadn’t deterred Charlie who announced, again with witnesses present, that he intended to move to Vancouver with a new paramour. That evening, when he returned to their room in the Empire, she was waiting for him.

“Don’t make me desperate or I’ll use this,” she supposedly said, indicating his straight razor which was lying on a table. When he shrugged her off she grabbed the razor and swung it wide, across his throat. In the delicate words of the news report, the force of her slashing motion “fairly sawed through the jugular, half-severing the head from the body in her frenzy”.

Such is based upon Belle’s statement to police as there were no witnesses.

Several doctors answered the call to the Empire Hotel within minutes, all to pronounce Charlie dead. City Police detectives Redgrave and Palmer were also soon on the scene where they found little to concern themselves with beyond having the body taken to the morgue and Belle taken into custody. Priority, at this point, was given to preventing her from harming herself.

Until the inquest later that afternoon Belle was confined to the city lockup while awaiting transfer to the provincial jail.

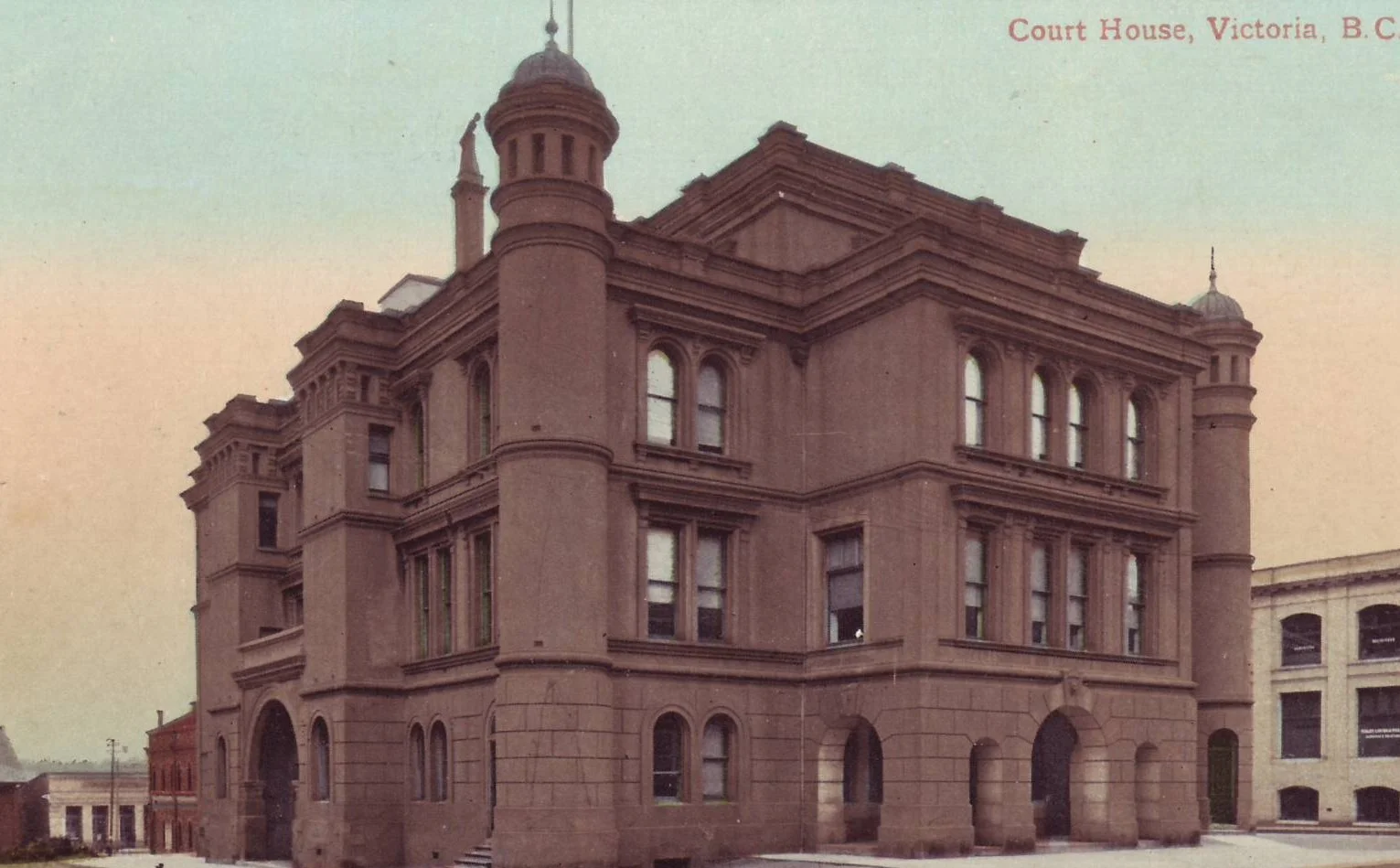

Four months later, Belle faced trial for murder, there having been a delay because of a missing key witness. It got off to a disappointing start, at least in the minds of the crowd of spectators, many of them women including witnesses and the curious, who were informed only at the last moment that the chief justice had been delayed on the mainland. However, 45 minutes later, proceedings did get underway in the provincial courthouse, Bastion Square.

The provincial courthouse, Victoria, where Belle stood trial for her lover’s murder which occurred only a few short blocks away.—Author’s Collection

When Mr. Justice Martin took his place on the bench, Crown counsel F.B. Gregory asked for an adjournment and it was agreed that the trial would begin the next morning before Mr. Justice Irving whose delayed arrival had held things up.

Once begun, the trial proceeded rapidly, with the Crown presenting its case in a single day. This led to a second adjournment after defence counsel George Powell said he wanted to change his slate of defence witnesses based upon the facts which had been presented.

Next morning, Charles Atkinson testified that Belle had waited for Kincaid at the hotel all through the evening of the murder, that she’d been distraught and had threatened to “dope” him. She told Atkinson that Charlie had threatened her on several occasions and had “chased” her.

Carrie Jackson, identified as a coloured woman, deposed that Belle had threatened several times to kill Kincaid, that he, in turn, had locked up his razors in fear of her doing so. Georgie Scudder and Retta Carmen, Kincaid’s latest love for whom he was going to leave Belle, confirmed her threats to Kincaid.

VPD Sgt. Hawton described the hotel room that the couple had shared. Incredibly, it “did not have any appearance of murder,” suggesting that the final argument, the slashing of Charlie’s throat and his flight down the stairs all happened so quickly that no blood was spilled in the room itself. Nor was there any upturned furniture or other visible evidence of a struggle.

Provincial Constable Murray made a brief appearance on the witness stand simply to verify that a witness, Robert Bruce, hadn’t been located but that he’d previously made a statement to police. Curiously, the gist of Bruce’s statement wasn’t made known to the court.

After Detective Palmer confirmed that the state of the hotel room shared by the couple, Detective Redgrave was asked about the statement taken from Belle upon her arrest. But this was disallowed, it having previously been suggested that the distraught woman might have been led by her interrogators.

Prosecutor Gregory then closed the case for the Crown.

Defence Counsel Powell explained to the bench that he’d been given a list of witnesses and their anticipated testimony by the Crown; but now, the prosecution having closed without them, without notice, he was taken by surprise, and he asked for a 20-minute adjournment to consider the implications.

Back in court, he requested an overnight adjournment. He needed, he said, to speak with some of these prospective witnesses to determine whether to call them for the defence. Short of this, “it would imperil his client to go on with the case”.

Judge Irving agreed, apologized to the jury for the inconvenience, and announced adjournment until 9 a.m. next morning.

It was thought that the third day of trial would be the last. But, come 5:30, rebuttal was incomplete and both counsels had yet to make their addresses to the court.

What was expected to be the most sensational part of the trial was Belle’s voluntary appearance in the witness box; by law she couldn’t be forced to take the stand.

Powell, it soon became apparent, was making a case for self-defence.

Under the headline, BELLE ADAMS SPEAKS, an unnamed Colonist reporter covered the testimony of numerous witnesses who appeared on Belle’s behalf and who spoke clearly enough to be heard throughout the courtroom. It was a different story when Belle took the stand to answer Powell’s questions in a voice so low that those in the reporters’ and public galleries could barely hear her.

(I have slightly edited the October 9, 1898 Colonist story which appeared on page eight, by the way, for brevity.)

BELLE ADAMS SPEAKS.

—

The Prisoner Voluntarily Enters the Witness Box and Gives Her Evidence.

—

Her Story of the Killing Is That She Acted in Self Defence.

—

...The sensational part of the proceedings yesterday was the putting of the prisoner in the box by the defence, to tell her story of the killing, which brings the whole question down to use of self-defence. The cross-examination of the prisoner was not entered upon by the Crown, but will be the first thing to come up tomorrow morning.

Mr. George E. Powell was well enough to attend yesterday, and conducted the examination of the prisoner, but the rest of the case was conducted for the defence by Mr. G.F. Cane, owing to Mr. Powell’s throat being in bad condition yet.

The first witness for the defence was Maud Baker, who said she saw Kincaid chase Belle Adams in the Empire Hotel with a razor, threatening to kill her, while the prisoner cried out, begging him not to. The witness said also that Georgie Scudder, one of the Crown’s witnesses, had said the prisoner ought to hang.

Mabel Brockway was called with the idea of showing that Georgie Scudder had a bias against the prisoner, while Frederick Kingsland, bartender of the Empire, said that just previous to the killing, he had heard a woman scream and say, “Oh, Charlie, don’t!”

Samuel Raby stated that the prisoner and Kincaid had frequent rows.

Frederick Gilmore was living at the Empire at the end of April or the beginning of May, while the prisoner and Kincaid lived there. He knew of a few little rows between them. One day he saw Kincaid chasing the prisoner from her room. She ran into the street, and Kincaid, who had a knife or razor in his hand, called foul names after her. The prisoner screamed as she left her room.

Ah Lok, a Chinaman [sic], who cleaned the rooms at the Empire hotel, saw Kincaid and the prisoner fighting once in their room at the Empire. When the row was on Charlie had a stick in his hand to hit the prisoner who ran into another room. Afterwards the two became amicable again. Charlie did not seem to be very angry while he stood outside the door, and was asking the prisoner to come back.

Fannie Lord said that Kincaid came after the prisoner one time when she was at witness’ house on Chatham Street. All that the witness had to tell was that the prisoner had left a satchel at her house, and that Kincaid came after it.

J.E. Hawkins, of Seattle, a coloured attorney [sic], knew the prisoner and Kincaid in Seattle, Kincaid there going by the name of Brown. They were living together there, and witness saw Kincaid make an assault upon the prisoner at Lake Washington with a razor.

On that occasion he saw Belle Adams running out of a room and Kincaid following with a knife, trying to cut her.

A man named Ernest Dallimore caught hold of Kincaid and held him, the knife dropping to the ground. Witness picked up the knife, and some days after returned it to Dallimore.

In cross-examination, witness said he was a member of the bar of Washington. He might have said that he would help the defence in this case if he could. He might possibly have said that Kincaid did not get half of what he deserved, and that Kincaid was no good. Witness denied having said since he came to Victoria that the knife was a dagger, and he had taken it from Kincaid. He did not recall saying that the blade was five inches long.

Mr. Burnes had seen the prisoner two weeks before the murder. Prisoner and Kincaid were squabbling over some money matters. Kincaid slapped her on the face and threatened to kill her, and then himself. Again, early on the morning of the murder, he heard an awful row in the room occupied by Kincaid and the prisoner at the Burnes House.

He rushed to the room, and Kincaid told him it was nothing; but the woman said Kincaid was trying to kill her. A little later he heard an unmerciful yell and, rushing back, opened the door and found Kincaid choking the woman.

Witness knuckled the man over, and Kincaid tried to get at the woman again. Witness stopped him, whereupon Kincaid said if he had his razor he would cut the woman’s throat. The woman was unconscious from the choking she received. Witness accompanied Kincaid out of the room to see he did not return, and threatened to call a policeman.

Cross-examined, the witness said it was 20 minutes before the woman came to after she was choked.

The woman herself was put in the box next. She told about the trouble at Lake Washington, when Kincaid abused her, and said she had had lots of of trouble with him in Victoria. He had threatened to kill her because she was going to leave him. This occurred several times, and he had two or three times threatened her with a razor. One of the times was when she ran out of the room at the Empire, and shut herself up in another room. He had also threatened her and struck her with his stick. It was because he threatened to kill her that she took her hand-bag to the Lord woman’s home [a hostel for women], and afterwards went to sleep at the Grand Pacific.

She got her trunk away to the Pritchard house [another refuge for women] once, and afterwards Kincaid followed her into Levy’s restaurant, and when she refused to go back with him, he threatened to kill her. Questioned about her row with [Retta Carmen], the prisoner said she had not made any threats against Kincaid’s life. In the course of the examination, a note written by the prisoner to Kincaid, saying she was leaving him, was read. She spoke so low, however, that a good deal of her testimony was inaudible to the body of the courtroom.

Coming down to the night of Kincaid’s killing, the prisoner said she had gone with him to his room at his request. He told her he had some business to attend to, and then went out. He returned about 9 o’clock, after having been away a couple of hours. She told him [that she was leaving him], and he replied:

”What are you waiting for; why don’t you get out and rustle?” She said she would not do it, and he replied that he could get a white girl to rustle for him.

He proceeded to call her names, caught hold of her and slapped her two or three times, and pushed her down on the floor.

He came at her and said he would fix her, and, taking a razor out, came straight towards her. She tried to get away from him, and started toward the door. He came at her again and caught hold of her, and in the scuffle the razor fell on the table, and he put up his hand to her lips.

Then she caught up the razor, and he came back at her, trying to recover the razor. She knew that if he did he would kill her and she made a cut at him with it while he held her. Then she saw blood and realized what she had done. Kincaid started from the door and went downstairs, she following.

The time being now 7:30...and in consequence of the impossibility of finishing before Saturday morning, Mr. Justice Irving adjourned the court till tomorrow at 9 o’clock.

(Editor’s Note: None of the female witnesses is identified by their occupations or relationship to Belle, which would suggest they were working prostitutes.)

* * * * *

As if wanting to put the whole sordid business to rest, the next Colonist headline got right to the point in just three words: IT IS MANSLAUGHTER and, two days later, FIVE YEARS’ SENTENCE.

Despite ample testimony to the effect that she’d been physically assaulted and threatened with death on several occasions, Belle Adams, “the white woman convicted of manslaughter in the death of her mulatto paramour,” was off to prison. Her sentencing by Justice Irving had been witnessed in a courtroom filled to overflowing with spectators.

Her lawyer attempted to have sentence postponed because he’d been disallowed the opportunity to rebut the testimony of a VPD detective named Purdue but Irving replied that his “anxiety throughout the trial [had been] to give the prisoner the benefit of any doubt”.

Just before Irving passed sentence, Mr. Powell reminded him that the jury had believed Belle’s story of repeated provocation, that she’d struck Kincaid down “in the heat of passion,” and they’d recommended mercy. Irving replied that the jury hadn’t, in fact, accepted her claim of self-defence—that the single, straight cut across Kincaid’s jugular was so clean that it could only have been effected by her taking him by surprise: “The depth of the cut showed the ferocity of the blow.”

Irving reminded Powell that Belle had known the type of man she was consorting with. His responsibility to the public, he said, was two-fold: that Belle’s sentence serve as a deterrent to others, and that her “suffering” deter her from re-offending.

All said and done, Belle was a fallen woman, a disgrace to her gender; in that hyper-critical era she was lucky to get off with just five years.

Was it self-defence or a fit of passion? By all accounts, Belle had every right to be deathly afraid of her no-longer lover who’d threatened to kill her several times in public and, once, choked her into unconsciousness. But, during their final frenzied struggle, when she managed to grab the razor from him, did she use it solely to save herself or was there malice in her action?

Ponder this quote, given as she knelt beside a bloodied and dead Charlie Kincaid at the entrance to the Empire Hotel: “I was mad to do it, I must have been, but, oh, I love you so!”

* * * * *

As the provincial penitentiary in New Westminster lacked a full-time women’s warden it was expected that Belle would serve her sentence in the Kingston Penitentiary.

Such is the sad story of Belle Adams aka Belle Pettie aka Zella Adams aka Zella Ward, the young woman with the horrible hat.

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.